Authenticated encryption

Authenticated Encryption (AE) is an encryption scheme which simultaneously assures the data confidentiality (also known as privacy: the encrypted message is impossible to understand without the knowledge of a secret key[1]) and authenticity (in other words, it is unforgeable:[2] the encrypted message includes an authentication tag that the sender can calculate only while possessing the secret key[1]). Examples of encryption modes that provide AE are GCM, CCM.[1]

Many (but not all) AE schemes allow the message to contain "associated data" (AD) which is not made confidential, but its integrity is protected (i.e., it is readable, but tampering with it will be detected). A typical example is the header of a network packet that contains its destination address. To properly route the packet, all intermediate nodes in the message path need to know the destination, but for security reasons they cannot possess the secret key.[3] Schemes that allow associated data provide authenticated encryption with associated data, or AEAD.[3]

Programming interface

A typical programming interface for an AE implementation provides the following functions:

- Encryption

- Input: plaintext, key, and optionally a header (also known as additional authenticated data, AAD or associated data, AD) in plaintext that will not be encrypted, but will be covered by authenticity protection.

- Output: ciphertext and authentication tag (message authentication code or MAC).

- Decryption

- Input: ciphertext, key, authentication tag, and optionally a header (if used during the encryption).

- Output: plaintext, or an error if the authentication tag does not match the supplied ciphertext or header.

The header part is intended to provide authenticity and integrity protection for networking or storage metadata for which confidentiality is unnecessary, but authenticity is desired.

History

The need for authenticated encryption emerged from the observation that securely combining separate confidentiality and authentication block cipher operation modes could be error prone and difficult.[4][5] This was confirmed by a number of practical attacks introduced into production protocols and applications by incorrect implementation, or lack of authentication ().[6]

Around the year 2000, a number of efforts evolved around the notion of standardizing modes that ensured correct implementation. In particular, strong interest in possibly secure modes was sparked by the publication of Charanjit Jutla's integrity-aware CBC and integrity-aware parallelizable, IAPM, modes[7] in 2000 (see OCB and chronology[8]). Six different authenticated encryption modes (namely offset codebook mode 2.0, OCB 2.0; Key Wrap; counter with CBC-MAC, CCM; encrypt then authenticate then translate, EAX; encrypt-then-MAC, EtM; and Galois/counter mode, GCM) have been standardized in ISO/IEC 19772:2009.[9] More authenticated encryption methods were developed in response to NIST solicitation.[10] Sponge functions can be used in duplex mode to provide authenticated encryption.[11]

Bellare and Namprempre (2000) analyzed three compositions of encryption and MAC primitives, and demonstrated that encrypting a message and subsequently applying a MAC to the ciphertext (the Encrypt-then-MAC approach) implies security against an adaptive chosen ciphertext attack, provided that both functions meet minimum required properties. Katz and Yung investigated the notion under the name "unforgeable encryption" and proved it implies security against chosen ciphertext attacks.[12]

In 2013, the CAESAR competition was announced to encourage design of authenticated encryption modes.[13]

In 2015, ChaCha20-Poly1305 is added as an alternative AE construction to GCM in IETF protocols.

Authenticated encryption with associated data

Authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD) is a variant of AE that allows the message to include "associated data" (AD, additional non-confidential information, a.k.a. "additional authenticated data", AAD). A recipient can check the integrity of both the associated data and the confidential information in a message. AD is useful, for example, in network packets where the header should be visible for routing, but the payload needs to be confidential, and both need integrity and authenticity. The notion of AEAD was formalized by Rogaway (2002).[3]

Approaches to authenticated encryption

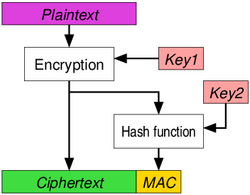

Encrypt-then-MAC (EtM)

The plaintext is first encrypted, then a MAC is produced based on the resulting ciphertext. The ciphertext and its MAC are sent together. Used in, e.g., IPsec.[14] The standard method according to ISO/IEC 19772:2009.[9] This is the only method which can reach the highest definition of security in AE, but this can only be achieved when the MAC used is "strongly unforgeable".[15] In November 2014, TLS and DTLS extension for EtM has been published as RFC 7366. Various EtM ciphersuites exist for SSHv2 as well (e.g., hmac-sha1-etm@openssh.com).

Note that key separation is mandatory (distinct keys must be used for encryption and for the keyed hash), otherwise it is potentially insecure depending on the specific encryption method and hash function used.[citation needed]

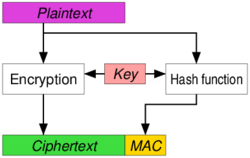

Encrypt-and-MAC (E&M)

A MAC is produced based on the plaintext, and the plaintext is encrypted without the MAC. The plaintext's MAC and the ciphertext are sent together. Used in, e.g., SSH.[16] Even though the E&M approach has not been proved to be strongly unforgeable in itself,[15] it is possible to apply some minor modifications to SSH to make it strongly unforgeable despite the approach.[17]

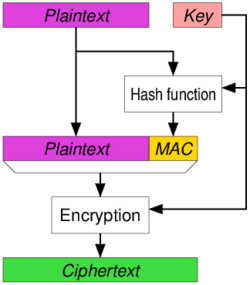

MAC-then-Encrypt (MtE)

A MAC is produced based on the plaintext, then the plaintext and MAC are together encrypted to produce a ciphertext based on both. The ciphertext (containing an encrypted MAC) is sent. AEAD is used in SSL/TLS.[18] Even though the MtE approach has not been proven to be strongly unforgeable in itself,[15] the SSL/TLS implementation has been proven to be strongly unforgeable by Krawczyk who showed that SSL/TLS was, in fact, secure because of the encoding used alongside the MtE mechanism.[19][dubious ] Despite the theoretical security, deeper analysis of SSL/TLS modeled the protection as MAC-then-pad-then-encrypt, i.e. the plaintext is first padded to the block size of the encryption function. Padding errors often result in the detectable errors on the recipient's side, which in turn lead to padding oracle attacks, such as Lucky Thirteen.

See also

- Block cipher mode of operation

- CCM mode

- CWC mode

- OCB mode

- EAX mode

- GCM

- GCM-SIV

- ChaCha20-Poly1305

- SGCM

- Signcryption

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Black 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Katz & Lindell 2020, p. 116.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Black 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ "A Conventional Authenticated-Encryption Mode". NIST. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/documents/proposedmodes/eax/eax-spec.pdf. "people had been doing rather poorly when they tried to glue together a traditional (privacy-only) encryption scheme and a message authentication code (MAC)"

- ↑ "The CWC Authenticated Encryption (Associated Data) Mode". NIST. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/documents/proposedmodes/cwc/cwc-spec.pdf. "it is very easy to accidentally combine secure encryption schemes with secure MACs and still get insecure authenticated encryption schemes"

- ↑ "Failures of secret-key cryptography". Daniel J. Bernstein. https://cr.yp.to/talks/2013.03.12/slides.pdf.

- ↑ Jutl, Charanjit S. (2000-08-01). "Encryption Modes with Almost Free Message Integrity". Cryptology ePrint Archive: Report 2000/039. IACR. https://eprint.iacr.org/2000/039.

- ↑ T. Krovetz; P. Rogaway (2011-03-01). "The Software Performance of Authenticated-Encryption Modes". Fast Software Encryption 2011 (FSE 2011) (IACR). https://web.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/papers/ae.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Information technology -- Security techniques -- Authenticated encryption". 19772:2009. ISO/IEC. https://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=46345.

- ↑ "Encryption modes development". NIST. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/modes_development.html.

- ↑ The Keccak Team. "Duplexing The Sponge". http://sponge.noekeon.org/SpongeDuplex.pdf.

- ↑ Katz, J.; Yung, M. (2001). "Unforgeable Encryption and Chosen Ciphertext Secure Modes of Operation". in B. Schneier. Fast Software Encryption (FSE): 2000 Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 1978. pp. 284–299. doi:10.1007/3-540-44706-7_20. ISBN 978-3-540-41728-6.

- ↑ "CAESAR: Competition for Authenticated Encryption: Security, Applicability, and Robustness". https://competitions.cr.yp.to/caesar.html.

- ↑ "Separate Confidentiality and Integrity Algorithms". RFC 4303. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4303#section-3.3.2.1.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Authenticated Encryption: Relations among notions and analysis of the generic composition paradigm". M. Bellare and C. Namprempre. https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~mihir/papers/oem.html.

- ↑ "Data Integrity". RFC 4253. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4253#section-6.4.

- ↑ Bellare, Mihir; Kohno, Tadayoshi; Namprempre, Chanathip. "Breaking and Provably Repairing the SSH Authenticated Encryption Scheme: A Case Study of the Encode-then-Encrypt-and-MAC Paradigm". ACM Transactions on Information and System Security. https://homes.cs.washington.edu/~yoshi/papers/SSH/ssh.pdf.

- ↑ Rescorla, Eric; Dierks, Tim (August 2008). "Record Payload Protection". RFC 5246 (Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)). https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5246#section-6.2.3. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ↑ "The Order of Encryption and Authentication for Protecting Communications (Or: How Secure is SSL?)". H. Krawczyk. https://www.iacr.org/archive/crypto2001/21390309.pdf.

- General

- Bellare, M.; Namprempre, C. (2000), "Authenticated Encryption: Relations among Notions and Analysis of the Generic Composition Paradigm", in T. Okamoto, Advances in Cryptology — ASIACRYPT 2000, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 1976, Springer-Verlag, pp. 531–545, doi:10.1007/3-540-44448-3_41, ISBN 978-3-540-41404-9, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/3-540-44448-3_41.pdf

Sources

- Katz, J.; Lindell, Y. (2020). Introduction to Modern Cryptography. Chapman & Hall/CRC Cryptography and Network Security Series. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-13301-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=RsoOEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT116. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- Black, J. (2005). "Authenticated encryption". Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security. Springer US. pp. 11–21. doi:10.1007/0-387-23483-7_15. ISBN 978-0-387-23473-1. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=2628d946bda9f3d3b087e5c4846e76ae0fb07b6b.

External links

- NIST: Modes Development

- How to choose an Authenticated Encryption mode

|