Connection (mathematics)

In geometry, the notion of a connection makes precise the idea of transporting local geometric objects, such as tangent vectors or tensors in the tangent space, along a curve or family of curves in a parallel and consistent manner. There are various kinds of connections in modern geometry, depending on what sort of data one wants to transport. For instance, an affine connection, the most elementary type of connection, gives a means for parallel transport of tangent vectors on a manifold from one point to another along a curve. An affine connection is typically given in the form of a covariant derivative, which gives a means for taking directional derivatives of vector fields, measuring the deviation of a vector field from being parallel in a given direction.

Connections are of central importance in modern geometry in large part because they allow a comparison between the local geometry at one point and the local geometry at another point. Differential geometry embraces several variations on the connection theme, which fall into two major groups: the infinitesimal and the local theory. The local theory concerns itself primarily with notions of parallel transport and holonomy. The infinitesimal theory concerns itself with the differentiation of geometric data. Thus a covariant derivative is a way of specifying a derivative of a vector field along another vector field on a manifold. A Cartan connection is a way of formulating some aspects of connection theory using differential forms and Lie groups. An Ehresmann connection is a connection in a fibre bundle or a principal bundle by specifying the allowed directions of motion of the field. A Koszul connection is a connection which defines directional derivative for sections of a vector bundle more general than the tangent bundle.

Connections also lead to convenient formulations of geometric invariants, such as the curvature (see also curvature tensor and curvature form), and torsion tensor.

Motivation: the unsuitability of coordinates

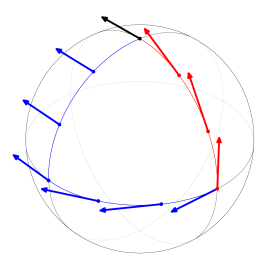

Consider the following problem. Suppose that a tangent vector to the sphere S is given at the north pole, and we are to define a manner of consistently moving this vector to other points of the sphere: a means for parallel transport. Naively, this could be done using a particular coordinate system. However, unless proper care is applied, the parallel transport defined in one system of coordinates will not agree with that of another coordinate system. A more appropriate parallel transportation system exploits the symmetry of the sphere under rotation. Given a vector at the north pole, one can transport this vector along a curve by rotating the sphere in such a way that the north pole moves along the curve without axial rolling. This latter means of parallel transport is the Levi-Civita connection on the sphere. If two different curves are given with the same initial and terminal point, and a vector v is rigidly moved along the first curve by a rotation, the resulting vector at the terminal point will be different from the vector resulting from rigidly moving v along the second curve. This phenomenon reflects the curvature of the sphere. A simple mechanical device that can be used to visualize parallel transport is the south-pointing chariot.

For instance, suppose that S is a sphere given coordinates by the stereographic projection. Regard S as consisting of unit vectors in R3. Then S carries a pair of coordinate patches corresponding to the projections from north pole and south pole. The mappings

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \varphi_0(x,y) & = \left(\frac{2x}{1+x^2+y^2}, \frac{2y}{1+x^2+y^2}, \frac{1-x^2-y^2}{1+x^2+y^2}\right)\\[8pt] \varphi_1(x,y) & = \left(\frac{2x}{1+x^2+y^2}, \frac{2y}{1+x^2+y^2}, \frac{x^2+y^2-1}{1+x^2+y^2}\right) \end{align} }[/math]

cover a neighborhood U0 of the north pole and U1 of the south pole, respectively. Let X, Y, Z be the ambient coordinates in R3. Then φ0 and φ1 have inverses

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \varphi_0^{-1}(X,Y,Z) &= \left(\frac{X}{Z+1}, \frac{Y}{Z+1}\right), \\[8pt] \varphi_1^{-1}(X,Y,Z) &= \left(\frac{-X}{Z-1}, \frac{-Y}{Z-1}\right), \end{align} }[/math]

so that the coordinate transition function is inversion in the circle:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{01}(x,y) = \varphi_0^{-1}\circ\varphi_1(x,y) = \left(\frac{x}{x^2+y^2},\frac{y}{x^2+y^2}\right) }[/math]

Let us now represent a vector field [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] on S (an assignment of a tangent vector to each point in S) in local coordinates. If P is a point of U0 ⊂ S, then a vector field may be represented by the pushforward of a vector field v0 on R2 by [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_0 }[/math]:

-

[math]\displaystyle{ v(P) = J_{\varphi_0}\left(\varphi_0^{-1}(P)\right) \cdot {\mathbf v}_0\left(\varphi_0^{-1}(P)\right) }[/math]

()

where [math]\displaystyle{ J_{\varphi_0} }[/math] denotes the Jacobian matrix of φ0 ([math]\displaystyle{ d{\varphi_0}_x({\mathbf u}) = J_{\varphi_0}(x)\cdot {\mathbf u} }[/math]), and v0 = v0(x, y) is a vector field on R2 uniquely determined by v (since the pushforward of a local diffeomorphism at any point is invertible). Furthermore, on the overlap between the coordinate charts U0 ∩ U1, it is possible to represent the same vector field with respect to the φ1 coordinates:

-

[math]\displaystyle{ v(P) = J_{\varphi_1}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right) \cdot {\mathbf v}_1\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right). }[/math]

()

To relate the components v0 and v1, apply the chain rule to the identity φ1 = φ0 o φ01:

- [math]\displaystyle{ J_{\varphi_1}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right) = J_{\varphi_0}\left(\varphi_0^{-1}(P)\right) \cdot J_{\varphi_{01}}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right). }[/math]

Applying both sides of this matrix equation to the component vector v1(φ1−1(P)) and invoking (1) and (2) yields

-

[math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbf v}_0\left(\varphi_0^{-1}(P)\right) = J_{\varphi_{01}}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right) \cdot {\mathbf v}_1 \left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P)\right). }[/math]

()

We come now to the main question of defining how to transport a vector field parallelly along a curve. Suppose that P(t) is a curve in S. Naïvely, one may consider a vector field parallel if the coordinate components of the vector field are constant along the curve. However, an immediate ambiguity arises: in which coordinate system should these components be constant?

For instance, suppose that v(P(t)) has constant components in the U1 coordinate system. That is, the functions v1(φ1−1(P(t))) are constant. However, applying the product rule to (3) and using the fact that dv1/dt = 0 gives

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d}{dt}{\mathbf v}_0\left(\varphi_0^{-1}(P(t))\right) = \left(\frac{d}{dt}J_{\varphi_{01}}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P(t))\right)\right) \cdot {\mathbf v}_1\left(\varphi_1^{-1}\left(P(t)\right)\right). }[/math]

But [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{d}{dt}J_{\varphi_{01}}\left(\varphi_1^{-1}(P(t))\right)\right) }[/math] is always a non-singular matrix (provided that the curve P(t) is not stationary), so v1 and v0 cannot ever be simultaneously constant along the curve.

Resolution

The problem observed above is that the usual directional derivative of vector calculus does not behave well under changes in the coordinate system when applied to the components of vector fields. This makes it quite difficult to describe how to translate vector fields in a parallel manner, if indeed such a notion makes any sense at all. There are two fundamentally different ways of resolving this problem.

The first approach is to examine what is required for a generalization of the directional derivative to "behave well" under coordinate transitions. This is the tactic taken by the covariant derivative approach to connections: good behavior is equated with covariance. Here one considers a modification of the directional derivative by a certain linear operator, whose components are called the Christoffel symbols, which involves no derivatives on the vector field itself. The directional derivative Duv of the components of a vector v in a coordinate system φ in the direction u are replaced by a covariant derivative:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_{\mathbf u} {\mathbf v} = D_{\mathbf u} {\mathbf v} + \Gamma(\varphi)\{{\mathbf u},{\mathbf v}\} }[/math]

where Γ depends on the coordinate system φ and is bilinear in u and v. In particular, Γ does not involve any derivatives on u or v. In this approach, Γ must transform in a prescribed manner when the coordinate system φ is changed to a different coordinate system. This transformation is not tensorial, since it involves not only the first derivative of the coordinate transition, but also its second derivative. Specifying the transformation law of Γ is not sufficient to determine Γ uniquely. Some other normalization conditions must be imposed, usually depending on the type of geometry under consideration. In Riemannian geometry, the Levi-Civita connection requires compatibility of the Christoffel symbols with the metric (as well as a certain symmetry condition). With these normalizations, the connection is uniquely defined.

The second approach is to use Lie groups to attempt to capture some vestige of symmetry on the space. This is the approach of Cartan connections. The example above using rotations to specify the parallel transport of vectors on the sphere is very much in this vein.

Historical survey of connections

Historically, connections were studied from an infinitesimal perspective in Riemannian geometry. The infinitesimal study of connections began to some extent with Elwin Christoffel. This was later taken up more thoroughly by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro and Tullio Levi-Civita (Levi-Civita Ricci) who observed in part that a connection in the infinitesimal sense of Christoffel also allowed for a notion of parallel transport.

The work of Levi-Civita focused exclusively on regarding connections as a kind of differential operator whose parallel displacements were then the solutions of differential equations. As the twentieth century progressed, Élie Cartan developed a new notion of connection. He sought to apply the techniques of Pfaffian systems to the geometries of Felix Klein's Erlangen program. In these investigations, he found that a certain infinitesimal notion of connection (a Cartan connection) could be applied to these geometries and more: his connection concept allowed for the presence of curvature which would otherwise be absent in a classical Klein geometry. (See, for example, (Cartan 1926) and (Cartan 1983).) Furthermore, using the dynamics of Gaston Darboux, Cartan was able to generalize the notion of parallel transport for his class of infinitesimal connections. This established another major thread in the theory of connections: that a connection is a certain kind of differential form.

The two threads in connection theory have persisted through the present day: a connection as a differential operator, and a connection as a differential form. In 1950, Jean-Louis Koszul (Koszul 1950) gave an algebraic framework for regarding a connection as a differential operator by means of the Koszul connection. The Koszul connection was both more general than that of Levi-Civita, and was easier to work with because it finally was able to eliminate (or at least to hide) the awkward Christoffel symbols from the connection formalism. The attendant parallel displacement operations also had natural algebraic interpretations in terms of the connection. Koszul's definition was subsequently adopted by most of the differential geometry community, since it effectively converted the analytic correspondence between covariant differentiation and parallel translation to an algebraic one.

In that same year, Charles Ehresmann (Ehresmann 1950), a student of Cartan's, presented a variation on the connection as a differential form view in the context of principal bundles and, more generally, fibre bundles. Ehresmann connections were, strictly speaking, not a generalization of Cartan connections. Cartan connections were quite rigidly tied to the underlying differential topology of the manifold because of their relationship with Cartan's equivalence method. Ehresmann connections were rather a solid framework for viewing the foundational work of other geometers of the time, such as Shiing-Shen Chern, who had already begun moving away from Cartan connections to study what might be called gauge connections. In Ehresmann's point of view, a connection in a principal bundle consists of a specification of horizontal and vertical vector fields on the total space of the bundle. A parallel translation is then a lifting of a curve from the base to a curve in the principal bundle which is horizontal. This viewpoint has proven especially valuable in the study of holonomy.

Possible approaches

- A rather direct approach is to specify how a covariant derivative acts on elements of the module of vector fields as a differential operator. More generally, a similar approach applies for connections in any vector bundle.

- Traditional index notation specifies the connection by components; see Christoffel symbols. (Note: this has three indices, but is not a tensor).

- In pseudo-Riemannian and Riemannian geometry the Levi-Civita connection is a special connection associated to the metric tensor.

- These are examples of affine connections. There is also a concept of projective connection, of which the Schwarzian derivative in complex analysis is an instance. More generally, both affine and projective connections are types of Cartan connections.

- Using principal bundles, a connection can be realized as a Lie algebra-valued differential form. See connection (principal bundle).

- An approach to connections which makes direct use of the notion of transport of "data" (whatever that may be) is the Ehresmann connection.

- The most abstract approach may be that suggested by Alexander Grothendieck, where a Grothendieck connection is seen as descent data from infinitesimal neighbourhoods of the diagonal; see (Osserman 2004).

See also

- Affine connection

- Cartan connection

- Ehresmann connection

- Grothendieck connection

- Levi-Civita connection

- Connection form

- Connection (fibred manifold)

- Connection (principal bundle)

- Connection (vector bundle)

- Connection (affine bundle)

- Connection (composite bundle)

- Connection (algebraic framework)

- Gauge theory (mathematics)

- Connes connection

References

- Levi-Civita, T.; Ricci, G. (1900), "Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications", Mathematische Annalen 54 (1–2): 125–201, doi:10.1007/BF01454201, https://zenodo.org/record/1428270

- Cartan, Élie (1924), "Sur les variétés à connexion projective", Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 52: 205–241, doi:10.24033/bsmf.1053

- Cartan, Élie (1926), "Les groupes d'holonomie des espaces généralisés", Acta Mathematica 48 (1–2): 1–42, doi:10.1007/BF02629755

- Cartan, Élie (1983), Geometry of Riemannian spaces, Math Sci Press, ISBN 978-0-915692-34-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=-YvvVfQ7xz4C

- Ehresmann, C. (1950), Les connexions infinitésimales dans un espace fibré différentiable, Colloque de Toplogie, Bruxelles, pp. 29–55

- Koszul, J. L. (1950), "Homologie et cohomologie des algèbres de Lie", Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 78: 65–127, doi:10.24033/bsmf.1410

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Connection", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=C/c025140

- Osserman, B. (2004), Connections, curvature, and p-curvature, http://math.berkeley.edu/~osserman/math/connections.pdf, retrieved 2007-02-04

- Mangiarotti, L.; Sardanashvily, G. (2000), Connections in Classical and Quantum Field Theory, World Scientific, ISBN 981-02-2013-8.

- Morita, Shigeyuki (2001), Geometry of Differential Forms, AMS, ISBN 0-8218-1045-6, https://archive.org/details/geometryofdiffer00mori

External links

- Connections at the Manifold Atlas

|