Gauge theory (mathematics)

In mathematics, and especially differential geometry and mathematical physics, gauge theory is the general study of connections on vector bundles, principal bundles, and fibre bundles. Gauge theory in mathematics should not be confused with the closely related concept of a gauge theory in physics, which is a field theory which admits gauge symmetry. In mathematics theory means a mathematical theory, encapsulating the general study of a collection of concepts or phenomena, whereas in the physical sense a gauge theory is a mathematical model of some natural phenomenon.

Gauge theory in mathematics is typically concerned with the study of gauge-theoretic equations. These are differential equations involving connections on vector bundles or principal bundles, or involving sections of vector bundles, and so there are strong links between gauge theory and geometric analysis. These equations are often physically meaningful, corresponding to important concepts in quantum field theory or string theory, but also have important mathematical significance. For example, the Yang–Mills equations are a system of partial differential equations for a connection on a principal bundle, and in physics solutions to these equations correspond to vacuum solutions to the equations of motion for a classical field theory, particles known as instantons.

Gauge theory has found uses in constructing new invariants of smooth manifolds, the construction of exotic geometric structures such as hyperkähler manifolds, as well as giving alternative descriptions of important structures in algebraic geometry such as moduli spaces of vector bundles and coherent sheaves.

History

Gauge theory has its origins as far back as the formulation of Maxwell's equations describing classical electromagnetism, which may be phrased as a gauge theory with structure group the circle group. Work of Paul Dirac on magnetic monopoles and relativistic quantum mechanics encouraged the idea that bundles and connections were the correct way of phrasing many problems in quantum mechanics. Gauge theory in mathematical physics arose as a significant field of study with the seminal work of Robert Mills and Chen-Ning Yang on so-called Yang–Mills gauge theory, which is now the fundamental model that underpins the standard model of particle physics.[1]

The mathematical investigation of gauge theory has its origins in the work of Michael Atiyah, Isadore Singer, and Nigel Hitchin on the self-duality equations on a Riemannian manifold in four dimensions.[2][3] In this work the moduli space of self-dual connections (instantons) on Euclidean space was studied, and shown to be of dimension [math]\displaystyle{ 8k-3 }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is a positive integer parameter. This linked up with the discovery by physicists of BPST instantons, vacuum solutions to the Yang–Mills equations in four dimensions with [math]\displaystyle{ k=1 }[/math]. Such instantons are defined by a choice of 5 parameters, the center [math]\displaystyle{ z\in \mathbb{R}^4 }[/math] and scale [math]\displaystyle{ \rho \in \mathbb{R}_{\gt 0} }[/math], corresponding to the [math]\displaystyle{ 8-3=5 }[/math]-dimensional moduli space. A BPST instanton is depicted to the right.

Around the same time Atiyah and Richard Ward discovered links between solutions to the self-duality equations and algebraic bundles over the complex projective space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{CP}^3 }[/math].[4] Another significant early discovery was the development of the ADHM construction by Atiyah, Vladimir Drinfeld, Hitchin, and Yuri Manin.[5] This construction allowed for the solution to the anti-self-duality equations on Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^4 }[/math] from purely linear algebraic data.

Significant breakthroughs encouraging the development of mathematical gauge theory occurred in the early 1980s. At this time the important work of Atiyah and Raoul Bott about the Yang–Mills equations over Riemann surfaces showed that gauge theoretic problems could give rise to interesting geometric structures, spurring the development of infinite-dimensional moment maps, equivariant Morse theory, and relations between gauge theory and algebraic geometry.[6] Important analytical tools in geometric analysis were developed at this time by Karen Uhlenbeck, who studied the analytical properties of connections and curvature proving important compactness results.[7] The most significant advancements in the field occurred due to the work of Simon Donaldson and Edward Witten.

Donaldson used a combination of algebraic geometry and geometric analysis techniques to construct new invariants of four manifolds, now known as Donaldson invariants.[8][9] With these invariants, novel results such as the existence of topological manifolds admitting no smooth structures, or the existence of many distinct smooth structures on the Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^4 }[/math] could be proved. For this work Donaldson was awarded the Fields Medal in 1986.

Witten similarly observed the power of gauge theory to describe topological invariants, by relating quantities arising from Chern–Simons theory in three dimensions to the Jones polynomial, an invariant of knots.[10] This work and the discovery of Donaldson invariants, as well as novel work of Andreas Floer on Floer homology, inspired the study of topological quantum field theory.

After the discovery of the power of gauge theory to define invariants of manifolds, the field of mathematical gauge theory expanded in popularity. Further invariants were discovered, such as Seiberg–Witten invariants and Vafa–Witten invariants.[11][12] Strong links to algebraic geometry were realised by the work of Donaldson, Uhlenbeck, and Shing-Tung Yau on the Kobayashi–Hitchin correspondence relating Yang–Mills connections to stable vector bundles.[13][14] Work of Nigel Hitchin and Carlos Simpson on Higgs bundles demonstrated that moduli spaces arising out of gauge theory could have exotic geometric structures such as that of hyperkähler manifolds, as well as links to integrable systems through the Hitchin system.[15][16] Links to string theory and mirror symmetry were realised, where gauge theory is essential to phrasing the homological mirror symmetry conjecture and the AdS/CFT correspondence.

Fundamental objects of interest

The fundamental objects of interest in gauge theory are connections on vector bundles and principal bundles. In this section we briefly recall these constructions, and refer to the main articles on them for details. The structures described here are standard within the differential geometry literature, and an introduction to the topic from a gauge-theoretic perspective can be found in the book of Donaldson and Peter Kronheimer.[17]

Principal bundles

The central objects of study in gauge theory are principal bundles and vector bundles. The choice of which to study is essentially arbitrary, as one may pass between them, but principal bundles are the natural objects from the physical perspective to describe gauge fields, and mathematically they more elegantly encode the corresponding theory of connections and curvature for vector bundles associated to them.

A principal bundle with structure group [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math], or a principal [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-bundle, consists of a quintuple [math]\displaystyle{ (P,X,\pi, G, \rho) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \pi: P \to X }[/math] is a smooth fibre bundle with fibre space isomorphic to a Lie group [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] represents a free and transitive right group action of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] which preserves the fibres, in the sense that for all [math]\displaystyle{ p\in P }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \pi(pg) = \pi(p) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ g\in G }[/math]. Here [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is the total space, and [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] the base space. Using the right group action for each [math]\displaystyle{ x\in X }[/math] and any choice of [math]\displaystyle{ p\in P_x }[/math], the map [math]\displaystyle{ g \mapsto pg }[/math] defines a diffeomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ P_x \cong G }[/math] between the fibre over [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and the Lie group [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] as smooth manifolds. Note however there is no natural way of equipping the fibres of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] with the structure of Lie groups, as there is no natural choice of element [math]\displaystyle{ p\in P_x }[/math] for every [math]\displaystyle{ x\in X }[/math].

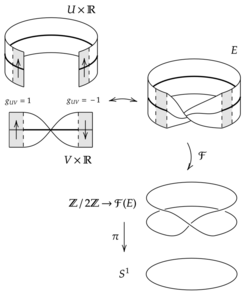

The simplest examples of principal bundles are given when [math]\displaystyle{ G=\operatorname{U}(1) }[/math] is the circle group. In this case the principal bundle has dimension [math]\displaystyle{ \dim P = n + 1 }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \dim X = n }[/math]. Another natural example occurs when [math]\displaystyle{ P=\mathcal{F}(TX) }[/math] is the frame bundle of the tangent bundle of the manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], or more generally the frame bundle of a vector bundle over [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. In this case the fibre of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is given by the general linear group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{GL}(n, \mathbb{R}) }[/math].

Since a principal bundle is a fibre bundle, it locally has the structure of a product. That is, there exists an open covering [math]\displaystyle{ \{U_{\alpha}\} }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and diffeomorphisms [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_\alpha: P_{U_\alpha} \to U_\alpha \times G }[/math] commuting with the projections [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{pr}_1 }[/math], such that the transition functions [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha\beta} :U_{\alpha}\cap U_{\beta} \to G }[/math] defined by [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_\alpha \circ \varphi_{\beta}^{-1} (x,g) = (x, g_{\alpha\beta}(x) g) }[/math] satisfy the cocycle condition

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha\beta}(x) g_{\beta\gamma}(x) = g_{\alpha\gamma}(x) }[/math]

on any triple overlap [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha}\cap U_{\beta}\cap U_\gamma }[/math]. In order to define a principal bundle it is enough to specify such a choice of transition functions, The bundle is then defined by gluing trivial bundles [math]\displaystyle{ U_\alpha\times G }[/math] along the intersections [math]\displaystyle{ U_\alpha\cap U_\beta }[/math] using the transition functions. The cocycle condition ensures precisely that this defines an equivalence relation on the disjoint union [math]\displaystyle{ \bigsqcup_\alpha U_\alpha \times G }[/math] and therefore that the quotient space [math]\displaystyle{ P=\bigsqcup_\alpha U_\alpha \times G/{\sim} }[/math] is well-defined. This is known as the fibre bundle construction theorem and the same process works for any fibre bundle described by transition functions, not just principal bundles or vector bundles.

Notice that a choice of local section [math]\displaystyle{ s_\alpha: U_\alpha \to P_{U_\alpha} }[/math] satisfying [math]\displaystyle{ \pi \circ s_\alpha = \operatorname{Id} }[/math] is an equivalent method of specifying a local trivialisation map. Namely, one can define [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_\alpha(p) = (\pi(p), \tilde s_\alpha(p)) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde s_\alpha(p)\in G }[/math] is the unique group element such that [math]\displaystyle{ p\tilde s_\alpha(p)^{-1} =s_\alpha(\pi(p)) }[/math].

Vector bundles

A vector bundle is a triple [math]\displaystyle{ (E, X, \pi) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \pi: E\to X }[/math] is a fibre bundle with fibre given by a vector space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{K}^r }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{K}=\mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C} }[/math] is a field. The number [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] is the rank of the vector bundle. Again one has a local description of a vector bundle in terms of a trivialising open cover. If [math]\displaystyle{ \{U_{\alpha}\} }[/math] is such a cover, then under the isomorphism

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{\alpha}: E_{U_{\alpha}} \to U_{\alpha} \times \mathbb{K}^r }[/math]

one obtains [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] distinguished local sections of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] corresponding to the [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] coordinate basis vectors [math]\displaystyle{ e_1,\dots,e_r }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{K}^r }[/math], denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{e}_1,\dots,\boldsymbol{e}_r }[/math]. These are defined by the equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{\alpha} (\boldsymbol{e}_i (x)) = (x, e_i). }[/math]

To specify a trivialisation it is therefore equivalent to give a collection of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] local sections which are everywhere linearly independent, and use this expression to define the corresponding isomorphism. Such a collection of local sections is called a frame.

Similarly to principal bundles, one obtains transition functions [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha\beta}: U_{\alpha}\cap U_{\beta} \to \operatorname{GL}(r, \mathbb{K}) }[/math] for a vector bundle, defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{\alpha} \circ \varphi_{\beta}^{-1} (x, v) = (x, g_{\alpha\beta}(x) v). }[/math]

If one takes these transition functions and uses them to construct the local trivialisation for a principal bundle with fibre equal to the structure group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{GL}(r, \mathbb{K}) }[/math], one obtains exactly the frame bundle of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], a principal [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{GL}(r, \mathbb{K}) }[/math]-bundle.

Associated bundles

Given a principal [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] and a representation [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] on a vector space [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math], one can construct an associated vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E=P\times_{\rho} V }[/math] with fibre the vector space [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]. To define this vector bundle, one considers the right action on the product [math]\displaystyle{ P\times V }[/math] defined by [math]\displaystyle{ (p,v)g = (pg, \rho(g^{-1})v) }[/math] and defines [math]\displaystyle{ P\times_{\rho} V = (P\times V)/G }[/math] as the quotient space with respect to this action.

In terms of transition functions the associated bundle can be understood more simply. If the principal bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] has transition functions [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha\beta} }[/math] with respect to a local trivialisation [math]\displaystyle{ \{U_{\alpha}\} }[/math], then one constructs the associated vector bundle using the transition functions [math]\displaystyle{ \rho \circ g_{\alpha\beta}: U_{\alpha}\cap U_{\beta} \to \operatorname{GL}(V) }[/math].

The associated bundle construction can be performed for any fibre space [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math], not just a vector space, provided [math]\displaystyle{ \rho: G\to \operatorname{Aut}(F) }[/math] is a group homomorphism. One key example is the capital A adjoint bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Ad}(P) }[/math] with fibre [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math], constructed using the group homomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \rho: G \to \operatorname{Aut}(G) }[/math] defined by conjugation [math]\displaystyle{ g \mapsto (h \mapsto g h g^{-1}) }[/math]. Note that despite having fibre [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math], the Adjoint bundle is neither a principal bundle, or isomorphic as a fibre bundle to [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] itself. For example, if [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is Abelian, then the conjugation action is trivial and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Ad}(P) }[/math] will be the trivial [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-fibre bundle over [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] regardless of whether or not [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is trivial as a fibre bundle. Another key example is the lowercase a adjoint bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) }[/math] constructed using the adjoint representation [math]\displaystyle{ \rho: G \to \operatorname{Aut}(\mathfrak{g}) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math] is the Lie algebra of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math].

Gauge transformations

A gauge transformation of a vector bundle or principal bundle is an automorphism of this object. For a principal bundle, a gauge transformation consists of a diffeomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi: P \to P }[/math] commuting with the projection operator [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] and the right action [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math]. For a vector bundle a gauge transformation is similarly defined by a diffeomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi: E \to E }[/math] commuting with the projection operator [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] which is a linear isomorphism of vector spaces on each fibre.

The gauge transformations (of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]) form a group under composition, called the gauge group, typically denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{G} }[/math]. This group can be characterised as the space of global sections [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{G} = \Gamma(\operatorname{Ad}(P)) }[/math] of the adjoint bundle, or [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{G} = \Gamma(\operatorname{Ad}(\mathcal{F} (E))) }[/math] in the case of a vector bundle, where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F}(E) }[/math] denotes the frame bundle.

One can also define a local gauge transformation as a local bundle isomorphism over a trivialising open subset [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math]. This can be uniquely specified as a map [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha} : U_{\alpha} \to G }[/math] (taking [math]\displaystyle{ G=\operatorname{GL}(r, \mathbb{K}) }[/math] in the case of vector bundles), where the induced bundle isomorphism is defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{\alpha}(p) = pg_{\alpha}(\pi(p)) }[/math]

and similarly for vector bundles.

Notice that given two local trivialisations of a principal bundle over the same open subset [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math], the transition function is precisely a local gauge transformation [math]\displaystyle{ g_{\alpha\alpha}: U_{\alpha} \to G }[/math]. That is, local gauge transformations are changes of local trivialisation for principal bundles or vector bundles.

Connections on principal bundles

A connection on a principal bundle is a method of connecting nearby fibres so as to capture the notion of a section [math]\displaystyle{ s: X\to P }[/math] being constant or horizontal. Since the fibres of an abstract principal bundle are not naturally identified with each other, or indeed with the fibre space [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] itself, there is no canonical way of specifying which sections are constant. A choice of local trivialisation leads to one possible choice, where if [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is trivial over a set [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math], then a local section could be said to be horizontal if it is constant with respect to this trivialisation, in the sense that [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_{\alpha} (s(x)) = (x, g) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ x\in U_{\alpha} }[/math] and one [math]\displaystyle{ g\in G }[/math]. In particular a trivial principal bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P=X\times G }[/math] comes equipped with a trivial connection.

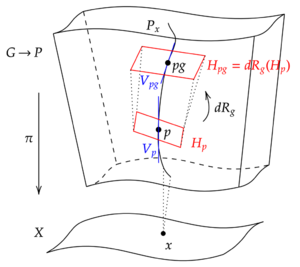

In general a connection is given by a choice of horizontal subspaces [math]\displaystyle{ H_p \subset T_p P }[/math] of the tangent spaces at every point [math]\displaystyle{ p\in P }[/math], such that at every point one has [math]\displaystyle{ T_p P = H_p \oplus V_p }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] is the vertical bundle defined by [math]\displaystyle{ V=\ker d\pi }[/math]. These horizontal subspaces must be compatible with the principal bundle structure by requiring that the horizontal distribution [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] is invariant under the right group action: [math]\displaystyle{ H_{pg} = d(R_g) (H_p) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ R_g: P \to P }[/math] denotes right multiplication by [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]. A section [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] is said to be horizontal if [math]\displaystyle{ T_p s \subset H_p }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] is identified with its image inside [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math], which is a submanifold of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] with tangent bundle [math]\displaystyle{ Ts }[/math]. Given a vector field [math]\displaystyle{ v\in \Gamma(TX) }[/math], there is a unique horizontal lift [math]\displaystyle{ v^{\#}\in \Gamma(H) }[/math]. The curvature of the connection [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] is given by the two-form with values in the adjoint bundle [math]\displaystyle{ F\in \Omega^2(X, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math] defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(v_1, v_2) = [v_1^{\#}, v_2^{\#}] - [v_1, v_2]^{\#} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ [\cdot, \cdot] }[/math] is the Lie bracket of vector fields. Since the vertical bundle consists of the tangent spaces to the fibres of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] and these fibres are isomorphic to the Lie group [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] whose tangent bundle is canonically identified with [math]\displaystyle{ TG = G\times \mathfrak{g} }[/math], there is a unique Lie algebra-valued two-form [math]\displaystyle{ F\in \Omega^2(P, \mathfrak{g}) }[/math] corresponding to the curvature. From the perspective of the Frobenius integrability theorem, the curvature measures precisely the extent to which the horizontal distribution fails to be integrable, and therefore the extent to which [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] fails to embed inside [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] as a horizontal submanifold locally.

The choice of horizontal subspaces may be equivalently expressed by a projection operator [math]\displaystyle{ \nu: TP \to V }[/math] which is equivariant in the correct sense, called the connection one-form. For a horizontal distribution [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math], this is defined by [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_H (h+v) = v }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ h+v }[/math] denotes the decomposition of a tangent vector with respect to the direct sum decomposition [math]\displaystyle{ TP = H\oplus V }[/math]. Due to the equivariance, this projection one-form may be taken to be Lie algebra-valued, giving some [math]\displaystyle{ \nu \in \Omega^1(P, \mathfrak{g}) }[/math].

A local trivialisation for [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is equivalently given by a local section [math]\displaystyle{ s_{\alpha}: U_{\alpha} \to P_{U_{\alpha}} }[/math] and the connection one-form and curvature can be pulled back along this smooth map. This gives the local connection one-form [math]\displaystyle{ A_{\alpha} = s_{\alpha}^* \nu\in \Omega^1(U_{\alpha}, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math] which takes values in the adjoint bundle of [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]. Cartan's structure equation says that the curvature may be expressed in terms of the local one-form [math]\displaystyle{ A_{\alpha} }[/math] by the expression

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = dA_\alpha + \frac{1}{2} [A_\alpha, A_\alpha] }[/math]

where we use the Lie bracket on the Lie algebra bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) }[/math] which is identified with [math]\displaystyle{ U_\alpha \times \mathfrak{g} }[/math] on the local trivialisation [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math].

Under a local gauge transformation [math]\displaystyle{ g: U_\alpha \to G }[/math] so that [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde A_{\alpha} = (g\circ s)^* \nu }[/math], the local connection one-form transforms by the expression

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde A_\alpha = \operatorname{ad}(g)\circ A_\alpha + (g^{-1})^* \theta }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] denotes the Maurer–Cartan form of the Lie group [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]. In the case where [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is a matrix Lie group, one has the simpler expression [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde A_{\alpha} = g A_\alpha g^{-1} - (dg)g^{-1}. }[/math]

Connections on vector bundles

A connection on a vector bundle may be specified similarly to the case for principal bundles above, known as an Ehresmann connection. However vector bundle connections admit a more powerful description in terms of a differential operator. A connection on a vector bundle is a choice of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{K} }[/math]-linear differential operator

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla: \Gamma(E) \to \Gamma(T^*X \otimes E) = \Omega^1(E) }[/math]

such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla(fs) = df\otimes s + f \nabla s }[/math]

for all [math]\displaystyle{ f\in C^{\infty}(X) }[/math] and sections [math]\displaystyle{ s\in \Gamma(E) }[/math]. The covariant derivative of a section [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] in the direction of a vector field [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] is defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_v (s) = \nabla s (v) }[/math]

where on the right we use the natural pairing between [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^1(X) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ TX }[/math]. This is a new section of the vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], thought of as the derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] in the direction of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math]. The operator [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_v }[/math] is the covariant derivative operator in the direction of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math]. The curvature of [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] is given by the operator [math]\displaystyle{ F_{\nabla}\in \Omega^2(\operatorname{End}(E)) }[/math] with values in the endomorphism bundle, defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_{\nabla}(v_1,v_2) = \nabla_{v_1} \nabla_{v_2} - \nabla_{v_2} \nabla_{v_1} - \nabla_{[v_1, v_2]}. }[/math]

In a local trivialisation the exterior derivative [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] acts as a trivial connection (corresponding in the principal bundle picture to the trivial connection discussed above). Namely for a local frame [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{e}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{e}_r }[/math] one defines

- [math]\displaystyle{ d (s^i \boldsymbol{e}_i) = ds^i \otimes \boldsymbol{e}_i }[/math]

where here we have used Einstein notation for a local section [math]\displaystyle{ s=s^i \boldsymbol{e}_i }[/math].

Any two connections [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_1, \nabla_2 }[/math] differ by an [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{End}(E) }[/math]-valued one-form [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. To see this, observe that the difference of two connections is [math]\displaystyle{ C^{\infty}(X) }[/math]-linear:

- [math]\displaystyle{ (\nabla_1 - \nabla_2)(fs) = f(\nabla_1-\nabla_2)(s). }[/math]

In particular since every vector bundle admits a connection (using partitions of unity and the local trivial connections), the set of connections on a vector bundle has the structure of an infinite-dimensional affine space modelled on the vector space [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^1(\operatorname{End}(E)) }[/math]. This space is commonly denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A} }[/math].

Applying this observation locally, every connection over a trivialising subset [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math] differs from the trivial connection [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] by some local connection one-form [math]\displaystyle{ A_{\alpha}\in \Omega^1(U_{\alpha}, \operatorname{End}(E)) }[/math], with the property that [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla = d + A_{\alpha} }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ U_{\alpha} }[/math]. In terms of this local connection form, the curvature may be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_A = dA_{\alpha} + A_{\alpha} \wedge A_{\alpha} }[/math]

where the wedge product occurs on the one-form component, and one composes endomorphisms on the endomorphism component. To link back to the theory of principal bundles, notice that [math]\displaystyle{ A\wedge A = \frac{1}{2}[A, A] }[/math] where on the right we now perform wedge of one-forms and commutator of endomorphisms.

Under a gauge transformation [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] of the vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], a connection [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] transforms into a connection [math]\displaystyle{ u\cdot \nabla }[/math] by the conjugation [math]\displaystyle{ (u\cdot \nabla)_v(s) = u(\nabla_v(u^{-1}(s)) }[/math]. The difference [math]\displaystyle{ u\cdot \nabla - \nabla = -(\nabla u)u^{-1} }[/math] where here [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] is acting on the endomorphisms of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. Under a local gauge transformation [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] one obtains the same expression

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde A_{\alpha} = g A_{\alpha} g^{-1} - (dg)g^{-1} }[/math]

as in the case of principal bundles.

Induced connections

A connection on a principal bundle induces connections on associated vector bundles. One way to see this is in terms of the local connection forms described above. Namely, if a principal bundle connection [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] has local connection forms [math]\displaystyle{ A_{\alpha}\in \Omega^1(U_{\alpha}, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \rho: G \to \operatorname{Aut}(V) }[/math] is a representation of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] defining an associated vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E=P\times_{\rho} V }[/math], then the induced local connection one-forms are defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_* A_{\alpha} \in \Omega^1(U_{\alpha}, \operatorname{End}(E)). }[/math]

Here [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_* }[/math] is the induced Lie algebra homomorphism from [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} \to \operatorname{End}(V) }[/math], and we use the fact that this map induces a homomorphism of vector bundles [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) \to \operatorname{End}(E) }[/math].

The induced curvature can be simply defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_* F_A \in \Omega^2(U_\alpha, \operatorname{End}(E)). }[/math]

Here one sees how the local expressions for curvature are related for principal bundles and vector bundles, as the Lie bracket on the Lie algebra [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math] is sent to the commutator of endomorphisms of [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{End}(V) }[/math] under the Lie algebra homomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_* }[/math].

Space of connections

The central object of study in mathematical gauge theory is the space of connections on a vector bundle or principal bundle. This is an infinite-dimensional affine space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A} }[/math] modelled on the vector space [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^1(X, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^1(X, \operatorname{End}(E)) }[/math] in the case of vector bundles). Two connections [math]\displaystyle{ A, A'\in \mathcal{A} }[/math] are said to be gauge equivalent if there exists a gauge transformation [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ A' = u\cdot A }[/math]. Gauge theory is concerned with gauge equivalence classes of connections. In some sense gauge theory is therefore concerned with the properties of the quotient space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A}/\mathcal{G} }[/math], which is in general neither a Hausdorff space or a smooth manifold.

Many interesting properties of the base manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] can be encoded in the geometry and topology of moduli spaces of connections on principal bundles and vector bundles over [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. Invariants of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], such as Donaldson invariants or Seiberg–Witten invariants can be obtained by computing numeral quantities derived from moduli spaces of connections over [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. The most famous application of this idea is Donaldson's theorem, which uses the moduli space of Yang–Mills connections on a principal [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{SU}(2) }[/math]-bundle over a simply connected four-manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] to study its intersection form. For this work Donaldson was awarded a Fields Medal.

Notational conventions

There are various notational conventions used for connections on vector bundles and principal bundles which will be summarised here.

- The letter [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is the most common symbol used to represent a connection on a vector bundle or principal bundle. It comes from the fact that if one chooses a fixed connection [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_0\in \mathcal{A} }[/math] of all connections, then any other connection may be written [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla = \nabla_0 + A }[/math] for some unique one-form [math]\displaystyle{ A\in \Omega^1(X, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math]. It also comes from the use of [math]\displaystyle{ A_{\alpha} }[/math] to denote the local form of the connection on a vector bundle, which subsequently comes from the electromagnetic potential [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] in physics. Sometimes the symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] is also used to refer to the connection form, usually on a principal bundle, and usually in this case [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] refers to the global connection one-form [math]\displaystyle{ \omega \in \Omega^1(P, \mathfrak{g}) }[/math] on the total space of the principal bundle, rather than the corresponding local connections forms. This convention is usually avoided in the mathematical literature as it often clashes with the use of [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] for a Kähler form when the underlying manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a Kähler manifold.

- The symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] is most commonly used to represent a connection on a vector bundle as a differential operator, and in that sense is used interchangeably with the letter [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. It is also used to refer to the covariant derivative operators [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_X }[/math]. Alternative notation for the connection operator and covariant derivative operators is [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_A }[/math] to emphasize the dependence on the choice of [math]\displaystyle{ A\in \mathcal{A} }[/math], or [math]\displaystyle{ D_A }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ d_A }[/math].

- The operator [math]\displaystyle{ d_A }[/math] most commonly refers to the exterior covariant derivative of a connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] (and so is sometimes written [math]\displaystyle{ d_{\nabla} }[/math] for a connection [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math]). Since the exterior covariant derivative in degree 0 is the same as the regular covariant derivative, the connection or covariant derivative itself is often denoted [math]\displaystyle{ d_A }[/math] instead of [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math].

- The symbol [math]\displaystyle{ F_A }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ F_{\nabla} }[/math] is most commonly used to refer to the curvature of a connection. When the connection is referred to by [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math], the curvature is referred to by [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] rather than [math]\displaystyle{ F_{\omega} }[/math]. Other conventions involve [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ R_A }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ R_{\nabla} }[/math], by analogy with the Riemannian curvature tensor in Riemannian geometry which is denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math].

- The letter [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] is often used to denote a principal bundle connection or Ehresmann connection when emphasis is to be placed on the horizontal distribution [math]\displaystyle{ H\subset TP }[/math]. In this case the vertical projection operator corresponding to [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] (the connection one-form on [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]) is usually denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math], or [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math], or [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math]. Using this convention the curvature is sometimes denoted [math]\displaystyle{ F_H }[/math] to emphasize the dependence, and [math]\displaystyle{ F_H }[/math] may refer to either the curvature operator on the total space [math]\displaystyle{ F_H \in \Omega^2(P, \mathfrak{g}) }[/math], or the curvature on the base [math]\displaystyle{ F_H \in \Omega^2(X, \operatorname{ad}(P)) }[/math].

- The Lie algebra adjoint bundle is usually denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) }[/math], and the Lie group adjoint bundle by [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Ad}(P) }[/math]. This disagrees with the convention in the theory of Lie groups, where [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Ad} }[/math] refers to the representation of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad} }[/math] refers to the Lie algebra representation of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math] on itself by the Lie bracket. In the Lie group theory the conjugation action (which defines the bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Ad}(P) }[/math]) is often denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ \Psi_g }[/math].

Dictionary of mathematical and physical terminology

The mathematical and physical fields of gauge theory involve the study of the same objects, but use different terminology to describe them. Below is a summary of how these terms relate to each other.

| Mathematics | Physics |

|---|---|

| Principal bundle | Instanton sector or charge sector |

| Structure group | Gauge group or local gauge group |

| Gauge group | Group of global gauge transformations or global gauge group |

| Gauge transformation | Gauge transformation or gauge symmetry |

| Change of local trivialisation | Local gauge transformation |

| Local trivialisation | Gauge |

| Choice of local trivialisation | Fixing a gauge |

| Functional defined on the space of connections | Lagrangian of gauge theory |

| Object does not change under the effects of a gauge transformation | Gauge invariance |

| Gauge transformations that are covariantly constant with respect to the connection | Global gauge symmetry |

| Gauge transformations which are not covariantly constant with respect to the connection | Local gauge symmetry |

| Connection | Gauge field or gauge potential |

| Curvature | Gauge field strength or field strength |

| Induced connection/covariant derivative on associated bundle | Minimal coupling |

| Section of associated vector bundle | Matter field |

| Term in Lagrangian functional involving multiple different quantities

(e.g. the covariant derivative applied to a section of an associated bundle, or a multiplication of two terms) |

Interaction |

| Section of real or complex (usually trivial) line bundle | (Real or complex) Scalar field |

As a demonstration of this dictionary, consider an interacting term of an electron-positron particle field and the electromagnetic field in the Lagrangian of quantum electrodynamics:[19]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L} = \bar\psi(i\gamma^\mu D_\mu - m)\psi - \frac{1}{4}F_{\mu\nu}F^{\mu\nu}, }[/math]

Mathematically this might be rewritten

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}= \langle \psi, ({D\!\!\!\!/}_A - m) \psi \rangle_{L^2} + \|F_A\|_{L^2}^2 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is a connection on a principal [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{U}(1) }[/math] bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is a section of an associated spinor bundle and [math]\displaystyle{ {D\!\!\!\!/}_A }[/math] is the induced Dirac operator of the induced covariant derivative [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_A }[/math] on this associated bundle. The first term is an interacting term in the Lagrangian between the spinor field (the field representing the electron-positron) and the gauge field (representing the electromagnetic field). The second term is the regular Yang–Mills functional which describes the basic non-interacting properties of the electromagnetic field (the connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]). The term of the form [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_A \psi }[/math] is an example of what in physics is called minimal coupling, that is, the simplest possible interaction between a matter field [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] and a gauge field [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math].

Yang–Mills theory

The predominant theory that occurs in mathematical gauge theory is Yang–Mills theory. This theory involves the study of connections which are critical points of the Yang–Mills functional defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{YM}(A) = \int_X \|F_A\|^2 \, d\mathrm{vol}_g }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ (X,g) }[/math] is an oriented Riemannian manifold with [math]\displaystyle{ d\mathrm{vol}_g }[/math] the Riemannian volume form and [math]\displaystyle{ \| \cdot \|^2 }[/math] an [math]\displaystyle{ L^2 }[/math]-norm on the adjoint bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) }[/math]. This functional is the square of the [math]\displaystyle{ L^2 }[/math]-norm of the curvature of the connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], so connections which are critical points of this function are those with curvature as small as possible (or higher local minima of [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{YM} }[/math]).

These critical points are characterised as solutions of the associated Euler–Lagrange equations, the Yang–Mills equations

- [math]\displaystyle{ d_A \star F_A = 0 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ d_A }[/math] is the induced exterior covariant derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_A }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{ad}(P) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \star }[/math] is the Hodge star operator. Such solutions are called Yang–Mills connections and are of significant geometric interest.

The Bianchi identity asserts that for any connection, [math]\displaystyle{ d_A F_A = 0 }[/math]. By analogy for differential forms a harmonic form [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] is characterised by the condition

- [math]\displaystyle{ d \star \omega = d \omega = 0. }[/math]

If one defined a harmonic connection by the condition that

- [math]\displaystyle{ d_A \star F_A = d_A F_A = 0 }[/math]

the then study of Yang–Mills connections is similar in nature to that of harmonic forms. Hodge theory provides a unique harmonic representative of every de Rham cohomology class [math]\displaystyle{ [\omega] }[/math]. Replacing a cohomology class by a gauge orbit [math]\displaystyle{ \{u\cdot A \mid u\in \mathcal{G}\} }[/math], the study of Yang–Mills connections can be seen as trying to find unique representatives for each orbit in the quotient space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A}/\mathcal{G} }[/math] of connections modulo gauge transformations.

Self-duality and anti-self-duality equations

In dimension four the Hodge star operator sends two-forms to two-forms, [math]\displaystyle{ \star: \Omega^2(X) \to \Omega^2(X) }[/math], and squares to the identity operator, [math]\displaystyle{ \star^2 = \operatorname{Id} }[/math]. Thus the Hodge star operating on two-forms has eigenvalues [math]\displaystyle{ \pm 1 }[/math], and the two-forms on an oriented Riemannian four-manifold split as a direct sum

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^2(X) = \Omega_+ (X) \oplus \Omega_-(X) }[/math]

into the self-dual and anti-self-dual two-forms, given by the [math]\displaystyle{ +1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math] eigenspaces of the Hodge star operator respectively. That is, [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \in \Omega^2(X) }[/math] is self-dual if [math]\displaystyle{ \star \alpha = \alpha }[/math], and anti-self dual if [math]\displaystyle{ \star \alpha = -\alpha }[/math], and every differential two-form admits a splitting [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha = \alpha_+ + \alpha_- }[/math] into self-dual and anti-self-dual parts.

If the curvature of a connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] on a principal bundle over a four-manifold is self-dual or anti-self-dual then by the Bianchi identity [math]\displaystyle{ d_A \star F_A = \pm d_A F_A = 0 }[/math], so the connection is automatically a Yang–Mills connection. The equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \star F_A = \pm F_A }[/math]

is a first order partial differential equation for the connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], and therefore is simpler to study than the full second order Yang–Mills equation. The equation [math]\displaystyle{ \star F_A = F_A }[/math] is called the self-duality equation, and the equation [math]\displaystyle{ \star F_A = -F_A }[/math] is called the anti-self-duality equation, and solutions to these equations are self-dual connections or anti-self-dual connections respectively.

Dimensional reduction

One way to derive new and interesting gauge-theoretic equations is to apply the process of dimensional reduction to the Yang–Mills equations. This process involves taking the Yang–Mills equations over a manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] (usually taken to be the Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ X=\mathbb{R}^4 }[/math]), and imposing that the solutions of the equations be invariant under a group of translational or other symmetries. Through this process the Yang–Mills equations lead to the Bogomolny equations describing monopoles on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^3 }[/math], Hitchin's equations describing Higgs bundles on Riemann surfaces, and the Nahm equations on real intervals, by imposing symmetry under translations in one, two, and three directions respectively.

Gauge theory in one and two dimensions

Here the Yang–Mills equations when the base manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is of low dimension is discussed. In this setting the equations simplify dramatically due to the fact that in dimension one there are no two-forms, and in dimension two the Hodge star operator on two-forms acts as [math]\displaystyle{ \star: \Omega^2(X) \to C^{\infty}(X) }[/math].

Yang–Mills theory

One may study the Yang–Mills equations directly on a manifold of dimension two. The theory of Yang–Mills equations when the base manifold is a compact Riemann surface was carried about by Michael Atiyah and Raoul Bott.[6] In this case the moduli space of Yang–Mills connections over a complex vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] admits various rich interpretations, and the theory serves as the simplest case to understand the equations in higher dimensions. The Yang–Mills equations in this case become

- [math]\displaystyle{ \star F_A = \lambda(E) \operatorname{Id}_E }[/math]

for some topological constant [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(E)\in \mathbb{C} }[/math] depending on [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. Such connections are called projectively flat, and in the case where the vector bundle is topologically trivial (so [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(E) = 0 }[/math]) they are precisely the flat connections.

When the rank and degree of the vector bundle are coprime, the moduli space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math] of Yang–Mills connections is smooth and has a natural structure of a symplectic manifold. Atiyah and Bott observed that since the Yang–Mills connections are projectively flat, their holonomy gives projective unitary representations of the fundamental group of the surface, so that this space has an equivalent description as a moduli space of projective unitary representations of the fundamental group of the Riemann surface, a character variety. The theorem of Narasimhan and Seshadri gives an alternative description of this space of representations as the moduli space of stable holomorphic vector bundles which are smoothly isomorphic to the [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math].[20] Through this isomorphism the moduli space of Yang–Mills connections gains a complex structure, which interacts with the symplectic structure of Atiyah and Bott to make it a compact Kähler manifold.

Simon Donaldson gave an alternative proof of the theorem of Narasimhan and Seshadri that directly passed from Yang–Mills connections to stable holomorphic structures.[21] Atiyah and Bott used this rephrasing of the problem to illuminate the intimate relationship between the extremal Yang–Mills connections and the stability of the vector bundles, as an infinite-dimensional moment map for the action of the gauge group [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{G} }[/math], given by the curvature map [math]\displaystyle{ A\mapsto F_A }[/math] itself. This observation phrases the Narasimhan–Seshadri theorem as a kind of infinite-dimensional version of the Kempf–Ness theorem from geometric invariant theory, relating critical points of the norm squared of the moment map (in this case Yang–Mills connections) to stable points on the corresponding algebraic quotient (in this case stable holomorphic vector bundles). This idea has been subsequently very influential in gauge theory and complex geometry since its introduction.

Nahm equations

The Nahm equations, introduced by Werner Nahm, are obtained as the dimensional reduction of the anti-self-duality in four dimensions to one dimension, by imposing translational invariance in three directions.[22] Concretely, one requires that the connection form [math]\displaystyle{ A=A_0 \,dx^0 + A_1 \,dx^1 + A_2 \,dx^2 + A_3 \,dx^3 }[/math] does not depend on the coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ x^1, x^2, x^3 }[/math]. In this setting the Nahm equations between a system of equations on an interval [math]\displaystyle{ I\subset \mathbb{R} }[/math] for four matrices [math]\displaystyle{ T_0, T_1, T_2, T_3 \in C^{\infty}(I, \mathfrak{g}) }[/math] satisfying the triple of equations

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{cases} \frac{dT_1}{dt} + [T_0, T_1] + [T_2, T_3] = 0\\ \frac{dT_2}{dt} + [T_0, T_2] + [T_3, T_1] = 0\\ \frac{dT_3}{dt} + [T_0, T_3] + [T_1, T_2] = 0. \end{cases} }[/math]

It was shown by Nahm that the solutions to these equations (which can be obtained fairly easily as they are a system of ordinary differential equations) can be used to construct solutions to the Bogomolny equations, which describe monopoles on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^3 }[/math]. Nigel Hitchin showed that solutions to the Bogomolny equations could be used to construct solutions to the Nahm equations, showing solutions to the two problems were equivalent.[23] Donaldson further showed that solutions to the Nahm equations are equivalent to rational maps of degree [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] from the complex projective line [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{CP}^1 }[/math] to itself, where [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is the charge of the corresponding magnetic monopole.[24]

The moduli space of solutions to the Nahm equations has the structure of a hyperkähler manifold.

Hitchin's equations and Higgs bundles

Hitchin's equations, introduced by Nigel Hitchin, are obtained as the dimensional reduction of the self-duality equations in four dimensions to two dimensions by imposing translation invariance in two directions.[25] In this setting the two extra connection form components [math]\displaystyle{ A_3 \,dx^3 + A_4 \,dx^4 }[/math] can be combined into a single complex-valued endomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi = A_3 + i A_4 }[/math], and when phrased in this way the equations become conformally invariant and therefore are natural to study on a compact Riemann surface rather than [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^2 }[/math]. Hitchin's equations state that for a pair [math]\displaystyle{ (A,\Phi) }[/math] on a complex vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ E\to \Sigma }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\in \Omega^{1,0}(\Sigma, \operatorname{End}(E)) }[/math], that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{cases} F_A + [\Phi, \Phi^*] = 0\\ \bar\partial_A \Phi = 0\end{cases} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \bar\partial_A }[/math] is the [math]\displaystyle{ (0,1) }[/math]-component of [math]\displaystyle{ d_A }[/math]. Solutions of Hitchin's equations are called Hitchin pairs.

Whereas solutions to the Yang–Mills equations on a compact Riemann surface correspond to projective unitary representations of the surface group, Hitchin showed that solutions to Hitchin's equations correspond to projective complex representations of the surface group. The moduli space of Hitchin pairs naturally has (when the rank and degree of the bundle are coprime) the structure of a Kähler manifold. Through an analogue of Atiyah and Bott's observation about the Yang–Mills equations, Hitchin showed that Hitchin pairs correspond to so-called stable Higgs bundles, where a Higgs bundle is a pair [math]\displaystyle{ (E, \Phi) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ E\to \Sigma }[/math] is a holomorphic vector bundle and [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi :E \to E\otimes K }[/math] is a holomorphic endomorphism of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] with values in the canonical bundle of the Riemann surface [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma }[/math]. This is shown through an infinite-dimensional moment map construction, and this moduli space of Higgs bundles also has a complex structure, which is different to that coming from the Hitchin pairs, leading to two complex structures on the moduli space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math] of Higgs bundles. These combine to give a third making this moduli space a hyperkähler manifold.

Hitchin's work was subsequently vastly generalised by Carlos Simpson, and the correspondence between solutions to Hitchin's equations and Higgs bundles over an arbitrary Kähler manifold is known as the nonabelian Hodge theorem.[26][27][28][29][30]

Gauge theory in three dimensions

Monopoles

The dimensional reduction of the Yang–Mills equations to three dimensions by imposing translational invariance in one direction gives rise to the Bogomolny equations for a pair [math]\displaystyle{ (A, \Phi) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathfrak{g} }[/math] is a family of matrices.[31] The equations are

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_A = \star d_A \Phi. }[/math]

When the principal bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P\to \mathbb{R}^3 }[/math] has structure group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{U}(1) }[/math] the circle group, solutions to the Bogomolny equations model the Dirac monopole describing a magnetic monopole in classical electromagnetism. The work of Nahm and Hitchin shows that when the structure group is the special unitary group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{SU}(2) }[/math] solutions to the monopole equations correspond to solutions to the Nahm equations, and by work of Donaldson these further correspond to rational maps from [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{CP}^1 }[/math] to itself of degree [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is the charge of the monopole. This charge is defined as the limit

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{R\to \infty} \int_{S_R} (\Phi, F_A) = 4\pi k }[/math]

of the integral of the pairing [math]\displaystyle{ (\Phi, F_A)\in \Omega^2(\mathbb{R}^3) }[/math] over spheres [math]\displaystyle{ S_R }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^3 }[/math] of increasing radius [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math].

Chern–Simons theory

Chern–Simons theory in 3 dimensions is a topological quantum field theory with an action functional proportional to the integral of the Chern–Simons form, a three-form defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Tr}(F_A \wedge A -\frac{1}{3} A\wedge A \wedge A). }[/math]

Classical solutions to the Euler–Lagrange equations of the Chern–Simons functional on a closed 3-manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] correspond to flat connections on the principal [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P\to X }[/math]. However, when [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] has a boundary the situation becomes more complicated. Chern–Simons theory was used by Edward Witten to express the Jones polynomial, a knot invariant, in terms of the vacuum expectation value of a Wilson loop in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{SU}(2) }[/math] Chern–Simons theory on the three-sphere [math]\displaystyle{ S^3 }[/math].[10] This was a stark demonstration of the power of gauge theoretic problems to provide new insight in topology, and was one of the first instances of a topological quantum field theory.

In the quantization of the classical Chern–Simons theory, one studies the induced flat or projectively flat connections on the principal bundle restricted to surfaces [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma \subset X }[/math] inside the 3-manifold. The classical state spaces corresponding to each surface are precisely the moduli spaces of Yang–Mills equations studied by Atiyah and Bott.[6] The geometric quantization of these spaces was achieved by Nigel Hitchin and Axelrod–Della Pietra–Witten independently, and in the case where the structure group is complex, the configuration space is the moduli space of Higgs bundles and its quantization was achieved by Witten.[32][33][34]

Floer homology

Andreas Floer introduced a type of homology on a 3-manifolds defined in analogy with Morse homology in finite dimensions.[35] In this homology theory, the Morse function is the Chern–Simons functional on the space of connections on an [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{SU}(2) }[/math] principal bundle over the 3-manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. The critical points are the flat connections, and the flow lines are defined to be the Yang–Mills instantons on [math]\displaystyle{ M\times I }[/math] that restrict to the critical flat connections on the two boundary components. This leads to instanton Floer homology. The Atiyah–Floer conjecture asserts that instanton Floer homology agrees with the Lagrangian intersection Floer homology of the moduli space of flat connections on the surface [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma\subset X }[/math] defining a Heegaard splitting of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], which is symplectic due to the observations of Atiyah and Bott.

In analogy with instanton Floer homology one may define Seiberg–Witten Floer homology where instantons are replaced with solutions of the Seiberg–Witten equations. By work of Clifford Taubes this is known to be isomorphic to embedded contact homology and subsequently Heegaard Floer homology.

Gauge theory in four dimensions

Gauge theory has been most intensively studied in four dimensions. Here the mathematical study of gauge theory overlaps significantly with its physical origins, as the standard model of particle physics can be thought of as a quantum field theory on a four-dimensional spacetime. The study of gauge theory problems in four dimensions naturally leads to the study of topological quantum field theory. Such theories are physical gauge theories that are insensitive to changes in the Riemannian metric of the underlying four-manifold, and therefore can be used to define topological (or smooth structure) invariants of the manifold.

Anti-self-duality equations

In four dimensions the Yang–Mills equations admit a simplification to the first order anti-self-duality equations [math]\displaystyle{ \star F_A = -F_A }[/math] for a connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] on a principal bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P\to X }[/math] over an oriented Riemannian four-manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math].[17] These solutions to the Yang–Mills equations represent the absolute minima of the Yang–Mills functional, and the higher critical points correspond to the solutions [math]\displaystyle{ d_A \star F_A = 0 }[/math] that do not arise from anti-self-dual connections. The moduli space of solutions to the anti-self-duality equations, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}_P }[/math], allows one to derive useful invariants about the underlying four-manifold.

This theory is most effective in the case where [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is simply connected. For example, in this case Donaldson's theorem asserts that if the four-manifold has negative-definite intersection form (4-manifold), and if the principal bundle has structure group the special unitary group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{SU}(2) }[/math] and second Chern class [math]\displaystyle{ c_2(P) = 1 }[/math], then the moduli space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}_P }[/math] is five-dimensional and gives a cobordism between [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] itself and a disjoint union of [math]\displaystyle{ b_2(X) }[/math] copies of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{CP}^2 }[/math] with its orientation reversed. This implies that the intersection form of such a four-manifold is diagonalisable. There are examples of simply connected topological four-manifolds with non-diagonalisable intersection form, such as the E8 manifold, so Donaldson's theorem implies the existence of topological four-manifolds with no smooth structure. This is in stark contrast with two or three dimensions, in which topological structures and smooth structures are equivalent: any topological manifold of dimension less than or equal to 3 has a unique smooth structure on it.

Similar techniques were used by Clifford Taubes and Donaldson to show that Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^4 }[/math] admits uncountably infinitely many distinct smooth structures. This is in stark contrast to any dimension other than four, where Euclidean space has a unique smooth structure.

An extension of these ideas leads to Donaldson theory, which constructs further invariants of smooth four-manifolds out of the moduli spaces of connections over them. These invariants are obtained by evaluating cohomology classes on the moduli space against a fundamental class, which exists due to analytical work showing the orientability and compactness of the moduli space by Karen Uhlenbeck, Taubes, and Donaldson.

When the four-manifold is a Kähler manifold or algebraic surface and the principal bundle has vanishing first Chern class, the anti-self-duality equations are equivalent to the Hermitian Yang–Mills equations on the complex manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. The Kobayashi–Hitchin correspondence proven for algebraic surfaces by Donaldson, and in general by Uhlenbeck and Yau, asserts that solutions to the HYM equations correspond to stable holomorphic vector bundles. This work gave an alternate algebraic description of the moduli space and its compactification, because the moduli space of semistable holomorphic vector bundles over a complex manifold is a projective variety, and therefore compact. This indicates one way of compactifying the moduli space of connections is to add in connections corresponding to semi-stable vector bundles, so-called almost Hermitian Yang–Mills connections.

Seiberg–Witten equations

During their investigation of supersymmetry in four dimensions, Edward Witten and Nathan Seiberg uncovered a system of equations now called the Seiberg–Witten equations, for a connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and spinor field [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math].[11] In this case the four-manifold must admit a SpinC structure, which defines a principal SpinC bundle [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] with determinant line bundle [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], and an associated spinor bundle [math]\displaystyle{ S^+ }[/math]. The connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is on [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], and the spinor field [math]\displaystyle{ \psi \in \Gamma(S^+) }[/math]. The Seiberg–Witten equations are given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{cases} F_A^+ = \psi \otimes \psi^* - \frac{1}{2} |\psi|^2\\ d_A \psi = 0.\end{cases} }[/math]

Solutions to the Seiberg–Witten equations are called monopoles. The moduli space of solutions to the Seiberg–Witten equations, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}_{\sigma} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] denotes the choice of Spin structure, is used to derive the Seiberg–Witten invariants. The Seiberg–Witten equations have an advantage over the anti-self-duality equations, in that the equations themselves may be perturbed slightly to give the moduli space of solutions better properties. To do this, an arbitrary self-dual two-form is added on to the first equation. For generic choices of metric [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] on the underlying four-manifold, and choice of perturbing two-form, the moduli space of solutions is a compact smooth manifold. In good circumstances (when the manifold [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is of simple type), this moduli space is zero-dimensional: a finite collection of points. The Seiberg–Witten invariant in this case is simply the number of points in the moduli space. The Seiberg–Witten invariants can be used to prove many of the same results as Donaldson invariants, but often with easier proofs which apply in more generality.

Gauge theory in higher dimensions

Hermitian Yang–Mills equations

A particular class of Yang–Mills connections are possible to study over Kähler manifolds or Hermitian manifolds. The Hermitian Yang–Mills equations generalise the anti-self-duality equations occurring in four-dimensional Yang–Mills theory to holomorphic vector bundles over Hermitian complex manifolds in any dimension. If [math]\displaystyle{ E\to X }[/math] is a holomorphic vector bundle over a compact Kähler manifold [math]\displaystyle{ (X,\omega) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is a Hermitian connection on [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] with respect to some Hermitian metric [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math]. The Hermitian Yang–Mills equations are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{cases} F_A^{0,2} = 0\\ \Lambda_{\omega} F_A = \lambda(E) \operatorname{Id}_E, \end{cases} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda(E)\in \mathbb{C} }[/math] is a topological constant depending on [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. These may be viewed either as an equation for the Hermitian connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] or for the corresponding Hermitian metric [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] with associated Chern connection [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. In four dimensions the HYM equations are equivalent to the ASD equations. In two dimensions the HYM equations correspond to the Yang–Mills equations considered by Atiyah and Bott. The Kobayashi–Hitchin correspondence asserts that solutions of the HYM equations are in correspondence with polystable holomorphic vector bundles. In the case of compact Riemann surfaces this is the theorem of Narasimhan and Seshadri as proven by Donaldson. For algebraic surfaces it was proven by Donaldson, and in general it was proven by Karen Uhlenbeck and Shing-Tung Yau.[13][14] This theorem is generalised in the nonabelian Hodge theorem by Simpson, and is in fact a special case of it where the Higgs field of a Higgs bundle [math]\displaystyle{ (E, \Phi) }[/math] is set to zero.[26]

Exceptional holonomy instantons

The effectiveness of solutions of the Yang–Mills equations in defining invariants of four-manifolds has led to interest that they may help distinguish between exceptional holonomy manifolds such as G2 manifolds in dimension 7 and Spin(7) manifolds in dimension 8, as well as related structures such as Calabi–Yau 6-manifolds and nearly Kähler manifolds.[36][37]

String theory

New gauge-theoretic problems arise out of superstring theory models. In such models the universe is 10 dimensional consisting of four dimensions of regular spacetime and a 6-dimensional Calabi–Yau manifold. In such theories the fields which act on strings live on bundles over these higher dimensional spaces, and one is interested in gauge-theoretic problems relating to them. For example, the limit of the natural field theories in superstring theory as the string radius approaches zero (the so-called large volume limit) on a Calabi–Yau 6-fold is given by Hermitian Yang–Mills equations on this manifold. Moving away from the large volume limit one obtains the deformed Hermitian Yang–Mills equation, which describes the equations of motion for a D-brane in the B-model of superstring theory. Mirror symmetry predicts that solutions to these equations should correspond to special Lagrangian submanifolds of the mirror dual Calabi–Yau.[38]

See also

- Gauge theory

- Introduction to gauge theory

- Gauge group (mathematics)

- Gauge symmetry (mathematics)

- Yang–Mills theory

- Yang–Mills equations

References

- ↑ Yang, C.N. and Mills, R.L., 1954. Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Physical review, 96(1), p. 191.

- ↑ Atiyah, M.F., Hitchin, N.J. and Singer, I.M., 1977. Deformations of instantons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 74(7), pp. 2662–2663.

- ↑ Atiyah, M.F., Hitchin, N.J. and Singer, I.M., 1978. Self-duality in four-dimensional Riemannian geometry. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 362(1711), pp. 425–461.

- ↑ Atiyah, M.F. and Ward, R.S., 1977. Instantons and algebraic geometry. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 55(2), pp. 117–124.

- ↑ Atiyah, M.F., Hitchin, N.J., Drinfeld, V.G. and Manin, Y.I., 1978. Construction of instantons. Physics Letters A, 65(3), pp. 185–187.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Atiyah, M.F. and Bott, R., 1983. The yang-mills equations over riemann surfaces. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 308(1505), pp. 523–615.

- ↑ Uhlenbeck, K.K., 1982. Connections with Lp bounds on curvature. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 83(1), pp. 31–42.

- ↑ Donaldson, S.K., 1983. An application of gauge theory to four-dimensional topology. Journal of Differential Geometry, 18(2), pp. 279–315.

- ↑ Donaldson, S.K., 1990. Polynomial invariants for smooth four-manifolds. Topology, 29(3), pp. 257–315.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Witten, E., 1989. Quantum field theory and the Jones polynomial. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 121(3), pp. 351–399.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Witten, Edward (1994), "Monopoles and four-manifolds.", Mathematical Research Letters, 1 (6): 769–796, arXiv:hep-th/9411102, Bibcode:1994MRLet...1..769W, doi:10.4310/MRL.1994.v1.n6.a13, MR 1306021, archived from the original on 2013-06-29

- ↑ Vafa, C. and Witten, E., 1994. A strong coupling test of S-duality. arXiv preprint hep-th/9408074.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Simon K. Donaldson, Anti self-dual Yang-Mills connections over complex algebraic surfaces and stable vector bundles, Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (3) 50 (1985), 1-26.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Karen Uhlenbeck and Shing-Tung Yau, On the existence of Hermitian–Yang-Mills connections in stable vector bundles.Frontiers of the mathematical sciences: 1985 (New York, 1985). Communications on Pure and Applied

- ↑ Hitchin, N.J., 1987. The self-duality equations on a Riemann surface. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 3(1), pp. 59–126.

- ↑ Simpson, Carlos T. Higgs bundles and local systems. Publications Mathématiques de l'IHÉS, Volume 75 (1992), pp. 5–95. http://www.numdam.org/item/PMIHES_1992__75__5_0/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Donaldson, S.K., Donaldson, S.K. and Kronheimer, P.B., 1990. The geometry of four-manifolds. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Bleecker, D., 2005. Gauge theory and variational principles. Courier Corporation.

- ↑ Peskin, Michael; Schroeder, Daniel (1995). An introduction to quantum field theory (Reprint ed.). Westview Press. ISBN:978-0201503975.

- ↑ Narasimhan, M.S. and Seshadri, C.S., 1965. Stable and unitary vector bundles on a compact Riemann surface. Annals of Mathematics, pp. 540–567.

- ↑ Donaldson, S.K., 1983. A new proof of a theorem of Narasimhan and Seshadri. Journal of Differential Geometry, 18(2), pp. 269–277.

- ↑ Nahm, W., 1983. All self-dual multimonopoles for arbitrary gauge groups. In Structural elements in particle physics and statistical mechanics (pp. 301–310). Springer, Boston, MA.

- ↑ Hitchin, N.J., 1983. On the construction of monopoles. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 89(2), pp. 145–190.

- ↑ Donaldson, S.K., 1984. Nahm's equations and the classification of monopoles. Communications in mathematical physics, 96(3), pp. 387–408.

- ↑ Hitchin, N.J., 1987. The self‐duality equations on a Riemann surface. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 3(1), pp. 59–126.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Simpson, C.T., 1988. Constructing variations of Hodge structure using Yang-Mills theory and applications to uniformization. Journal of the American Mathematical Society, 1(4), pp. 867–918.

- ↑ Simpson, C.T., 1992. Higgs bundles and local systems. Publications Mathématiques de l'IHÉS, 75, pp. 5–95.

- ↑ Simpson, C.T., 1994. Moduli of representations of the fundamental group of a smooth projective variety I. Publications Mathématiques de l'IHÉS, 79, pp.47–129.

- ↑ Simpson, C.T. Moduli of representations of the fundamental group of a smooth projective variety. II. Publications Mathématiques de L’Institut des Hautes Scientifiques 80, 5–79 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02698895

- ↑ Simpson, C., 1996. The Hodge filtration on nonabelian cohomology. arXiv preprint alg-geom/9604005.

- ↑ Atiyah, Michael; Hitchin, Nigel (1988), The geometry and dynamics of magnetic monopoles, M. B. Porter Lectures, Princeton University Press, ISBN:978-0-691-08480-0, MR 0934202

- ↑ Hitchin, N.J., 1990. Flat connections and geometric quantization. Communications in mathematical physics, 131(2), pp. 347–380.

- ↑ Axelrod, S., Della Pietra, S. and Witten, E., 1991. Geometric quantization of Chern–Simons gauge theory. representations, 34, p. 39.

- ↑ Witten, E., 1991. Quantization of Chern-Simons gauge theory with complex gauge group. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 137(1), pp. 29–66.

- ↑ Floer, A., 1988. An instanton-invariant for 3-manifolds. Communications in mathematical physics, 118(2), pp. 215–240.

- ↑ S. K. Donaldson and R. P. Thomas. Gauge theory in higher dimensions. In The Geometric Universe (Oxford, 1996), pages 31–47. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1998.

- ↑ Simon Donaldson and Ed Segal. Gauge theory in higher dimensions, II. InSurveys in differential geometry. Volume XVI. Geometry of special holonomyand related topics, volume 16 ofSurv. Differ. Geom., pages 1–41. Int. Press, Somerville, MA, 2011.

- ↑ Leung, N.C., Yau, S.T. and Zaslow, E., 2000. From special lagrangian to hermitian-Yang-Mills via Fourier-Mukai transform. arXiv preprint math/0005118.

|