Biology:L-form bacteria

L-form bacteria, also known as L-phase bacteria, L-phase variants or cell wall-deficient bacteria (CWDB), are growth forms derived from different bacteria. They lack cell walls.[1] Two types of L-forms are distinguished: unstable L-forms, spheroplasts that are capable of dividing, but can revert to the original morphology, and stable L-forms, L-forms that are unable to revert to the original bacteria.

Discovery and early studies

L-form bacteria were first isolated in 1935 by Emmy Klieneberger-Nobel, who named them "L-forms" after the Lister Institute in London where she was working.[2]

She first interpreted these growth forms as symbionts related to pleuropneumonia-like organisms (PPLOs, later commonly called mycoplasmas).[3] Mycoplasmas (now in scientific classification called Mollicutes), parasitic or saprotrophic species of bacteria, also lack a cell wall (peptidoglycan/murein is absent).[4][5] Morphologically, they resemble L-form bacteria. Therefore, mycoplasmas formerly were sometimes considered stable L-forms or, because of their small size, even viruses, but phylogenetic analysis has identified them as bacteria that have lost their cell walls in the course of evolution.[6] Both, mycoplasmas and L-form bacteria are resistant against penicillin.

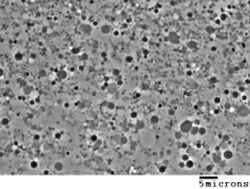

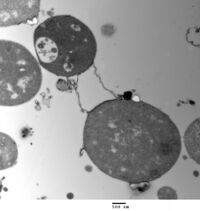

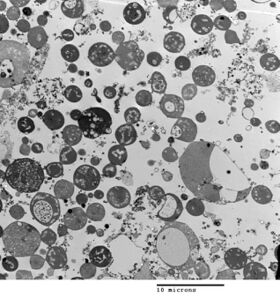

After the discovery of PPLOs (mycoplasmas/Mollicutes) and L-form bacteria, their mode of reproduction (proliferation) became a major subject of discussion. In 1954, using phase-contrast microscopy, continual observations of live cells have shown that L-form bacteria (previously also called L-phase bacteria) and pleuropneumonia-like organisms (PPLOs, now mycoplasmas/Mollicutes) ) do not proliferate by binary fission, but by a uni- or multi-polar budding mechanism. Microphotograph series of growing microcultures of different strains of L-form bacteria, PPLOs and, as a control, a Micrococcus species (dividing by binary fission) have been presented.[3] Additionally, electron microscopic studies have been performed.[7]

Appearance and cell division

Bacterial morphology is determined by the cell wall. Since the L-form has no cell wall, its morphology is different from that of the strain of bacteria from which it is derived. Typical L-form cells are spheres or spheroids. For example, L-forms of the rod-shaped bacterium Bacillus subtilis appear round when viewed by phase contrast microscopy or by transmission electron microscopy.[8]

Although L-forms can develop from Gram-positive as well as from Gram-negative bacteria, in a Gram stain test, the L-forms always colour Gram-negative, due to the lack of a cell wall.

The cell wall is important for cell division, which, in most bacteria, occurs by binary fission. This process usually requires a cell wall and components of the bacterial cytoskeleton such as FtsZ. The ability of L-form bacteria and mycoplasmas to grow and divide in the absence of both of these structures is highly unusual, and may represent a form of cell division that was important in early forms of life. This mode of division seems to involve the extension of thin protrusions from the cell's surface and these protrusions then pinching off to form new cells. The lack of cell wall in L-forms means that division is disorganised, giving rise to a variety of cell sizes, from very tiny to very big.[1]

Generation in cultures

L-forms can be generated in the laboratory from many bacterial species that usually have cell walls, such as Bacillus subtilis or Escherichia coli. This is done by inhibiting peptidoglycan synthesis with antibiotics or treating the cells with lysozyme, an enzyme that digests cell walls. The L-forms are generated in a culture medium that is the same osmolarity as the bacterial cytosol (an isotonic solution), which prevents cell lysis by osmotic shock.[2] L-form strains can be unstable, tending to revert to the normal form of the bacteria by regrowing a cell wall, but this can be prevented by long-term culture of the cells under the same conditions that were used to produce them – letting the wall-disabling mutations to accumulate by genetic drift.[9]

Some studies have identified mutations that occur, as these strains are derived from normal bacteria.[1][2] One such point mutation D92E is in an enzyme yqiD/ispA (P54383) involved in the mevalonate pathway of lipid metabolism that increased the frequency of L-form formation 1,000-fold.[1] The reason for this effect is not known, but it is presumed that the increase is related to this enzyme's role in making a lipid important in peptidoglycan synthesis.

Another methodology of induction relies on nanotechnology and landscape ecology. Microfluidics devices can be built in order to challenge peptidoglycan synthesis by extreme spatial confinement. After biological dispersal through a constricted (sub-micrometre scale) biological corridor connecting adjacent micro habitat patches, L-form-like cells can be derived[10] using a microfluifics-based (synthetic) ecosystem implementing an adaptive landscape[11] selecting for shape-shifting phenotypes similar to L-forms.

Significance and applications

Some publications have suggested that L-form bacteria might cause diseases in humans,[12] and other animals[13] but, as the evidence that links these organisms to disease is fragmentary and frequently contradictory, this hypothesis remains controversial.[14][15] The two extreme viewpoints on this question are that L-form bacteria are either laboratory curiosities of no clinical significance or important but unappreciated causes of disease.[5] Research on L-form bacteria is continuing. For example, L-form organisms have been observed in mouse lungs after experimental inoculation with Nocardia caviae,[16][17] and a recent study suggested that these organisms may infect immunosuppressed patients having undergone bone marrow transplants.[18] The formation of strains of bacteria lacking cell walls has also been proposed to be important in the acquisition of bacterial antibiotic resistance.[19][20]

L-form bacteria may be useful in research on early forms of life, and in biotechnology. These strains are being examined for possible uses in biotechnology as host strains for recombinant protein production.[21][22][23] Here, the absence of a cell wall can allow production of large amounts of secreted proteins that would otherwise accumulate in the periplasmic space of bacteria.[24][25]

L-form bacteria are seen as a persister cells, and a source of recurrent infection that has become of medical interest.[26]

See also

- Mycoplasmataceae—lack peptidoglycan but supplement their membranes with sterols for stability.

- Protoplast

- Spheroplast

- Ultramicrobacteria

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Life without a wall or division machine in Bacillus subtilis". Nature 457 (7231): 849–53. February 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07742. PMID 19212404. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457..849L.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Unstable Escherichia coli L Forms Revisited: Growth Requires Peptidoglycan Synthesis". J. Bacteriol. 189 (18): 6512–20. September 2007. doi:10.1128/JB.00273-07. PMID 17586646.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kandler, Gertraud; Kandler, Otto (1954). (Article in English available). "Untersuchungen über die Morphologie und die Vermehrung der pleuropneumonie-ähnlichen Organismen und der L-Phase der Bakterien. I. Lichtmikroskopische Untersuchungen" (in German). Archiv für Mikrobiologie 21 (2): 178–201. doi:10.1007/BF01816378. PMID 14350641. https://badw.de/fileadmin/members/K/1501/1954-Kandler_Kandler-PPLO-I-English2015-03-11.pdf.

- ↑ "Molecular Biology and Pathogenicity of Mycoplasmas". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 (4): 1094–156. December 1998. doi:10.1128/MMBR.62.4.1094-1156.1998. PMID 9841667.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Bacterial persistence and expression of disease". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10 (2): 320–44. April 1997. doi:10.1128/CMR.10.2.320. PMID 9105757. Full PDF

- ↑ Woese, Carl R.; Maniloff, J.; Zablen, L. B. (1980). "Phylogenetic analysis of the mycoplasmas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 77 (1): 494–498. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.1.494. PMID 6928642. PMC 348298. Bibcode: 1980PNAS...77..494W. https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/77/1/494.full.pdf.

- ↑ Kandler, Gertraud; Kandler, Otto; Huber, Oskar (1954). (Article in English available). "Untersuchungen über die Morphologie und die Vermehrung der pleuropneumonie-ähnlichen Organismen und der L-Phase der Bakterien. II. Elektronenmikroskopische Untersuchungen" (in German). Archiv für Mikrobiologie 21 (2): 202–216. doi:10.1007/BF01816379. PMID 1435064. https://badw.de/fileadmin/members/K/1501/1954-Kandler_Kandler-PPLO-II-English2015-03-11.pdf.

- ↑ "Characterization of a Stable L-Form of Bacillus subtilis 168". J. Bacteriol. 113 (1): 486–99. January 1973. doi:10.1128/JB.113.1.486-499.1973. PMID 4631836.

- ↑ Allan EJ (April 1991). "Induction and cultivation of a stable L-form of Bacillus subtilis". Journal of Applied Bacteriology 70 (4): 339–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02946.x. PMID 1905284.

- ↑ Männik J.; R. Driessen; P. Galajda; J.E. Keymer; C. Dekker (September 2009). "Bacterial growth and motility in sub-micron constrictions". PNAS 106 (35): 14861–14866. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907542106. PMID 19706420. PMC 2729279. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10614861M. https://works.bepress.com/jaan_mannik/4/download/.

- ↑ Keymer J.E.; P. Galajda; C. Muldoon R.; R. Austin (November 2006). "Bacterial metapopulations in nanofabricated landscapes". PNAS 103 (46): 17290–295. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607971103. PMID 17090676. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10317290K.

- ↑ "Identification of spheroplast-like agents isolated from tissues of patients with Crohn's disease and control tissues by polymerase chain reaction". J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (5): 1241–5. 1993. doi:10.1128/JCM.31.5.1241-1245.1993. PMID 8501224.

- ↑ "Identification of cell wall deficient forms of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in paraffin embedded tissues from animals with Johne's disease by in situ hybridization". J. Microbiol. Methods 42 (2): 185–95. 2000. doi:10.1016/S0167-7012(00)00185-8. PMID 11018275.

- ↑ "Cell wall-deficient bacteria as a cause of infections: a review of the clinical significance". J. Int. Med. Res. 33 (1): 1–20. 2005. doi:10.1177/147323000503300101. PMID 15651712. Archived from the original on 24 August 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090824140149/http://www.jimronline.net/content/full/2005/58/0545.pdf.

- ↑ Casadesús J (December 2007). "Bacterial L-forms require peptidoglycan synthesis for cell division". BioEssays 29 (12): 1189–91. doi:10.1002/bies.20680. PMID 18008373.

- ↑ Beaman BL (July 1980). "Induction of L-phase variants of Nocardia caviae within intact murine lungs". Infect. Immun. 29 (1): 244–51. doi:10.1128/IAI.29.1.244-251.1980. PMID 7399704.

- ↑ "Role of L-forms of Nocardia caviae in the development of chronic mycetomas in normal and immunodeficient murine models". Infect. Immun. 33 (3): 893–907. September 1981. doi:10.1128/IAI.33.3.893-907.1981. PMID 7287189.

- ↑ "Cell-wall-deficient bacteria and culture-negative febrile episodes in bone-marrow-transplant recipients". Lancet 357 (9257): 675–9. March 2001. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04131-3. PMID 11247551.

- ↑ "β-Lactam Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Cells That Do Not Require a Cell Wall for Integrity". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 (12): 5075–80. December 2005. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.12.5075-5080.2005. PMID 16304175.

- ↑ Mickiewicz, Katarzyna M.; Kawai, Yoshikazu; Drage, Lauren; Gomes, Margarida C.; Davison, Frances; Pickard, Robert; Hall, Judith; Mostowy, Serge et al. (2019). "Possible role of L-form switching in recurrent urinary tract infection". Nature Communications 10 (1): 4379. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12359-3. PMID 31558767. Bibcode: 2019NatCo..10.4379M.

- ↑ Sieben, Stefan (April 1998). "Die stabilen Protoplasten-Typ L-Formen von Proteus mirabilis als neues Expressionssystem für sekretorische Proteine und integrale Mempranproteine". Dissertation Universität Jena. OCLC 246350676.

- ↑ "The Serratia marcescens hemolysin is secreted but not activated by stable protoplast-type L-forms of Proteus mirabilis.". Arch. Microbiol. 170 (4): 236–42. October 1998. doi:10.1007/s002030050638. PMID 9732437. Bibcode: 1998ArMic.170..236S.

- ↑ "Use of cell wall-less bacteria (L-forms) for efficient expression and secretion of heterologous gene products". Current Opinion in Biotechnology 9 (5): 506–9. October 1998. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(98)80037-2. PMID 9821280.

- ↑ "Procaryotic Expression of Single-Chain Variable-Fragment (scFv) Antibodies: Secretion in L-Form Cells of Proteus mirabilis Leads to Active Product and Overcomes the Limitations of Periplasmic Expression in Escherichia coli". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 (12): 4862–9. 1 December 1998. doi:10.1128/AEM.64.12.4862-4869.1998. PMID 9835575. Bibcode: 1998ApEnM..64.4862R.

- ↑ "Secretory and extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64 (5): 625–35. June 2004. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1559-9. PMID 14966662.

- ↑ "Repurposing drugs with specific activity against L-form bacteria". Front Microbiol 14: 1097413. 2023. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1097413. PMID 37082179.

Further reading

- Domingue, Gerald J. (1982). Cell wall-deficient bacteria: basic principles and clinical significance. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-201-10162-1.

- Mattman, Lida H. (2001). Cell wall deficient forms: stealth pathogens. Boca Raton: CRC. ISBN 978-0-8493-8767-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=mincr2Hi81UC&pg=frontpage.

External links

- Errington Group at Newcastle University

- Scientists explore new window on the origins of life 2009 Newcastle University press release

|