Biology:Piper cubeba

| Cubeb | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Piperales |

| Family: | Piperaceae |

| Genus: | Piper |

| Species: | P. cubeba

|

| Binomial name | |

| Piper cubeba L.f.

| |

Piper cubeba, cubeb or tailed pepper is a plant in genus Piper, cultivated for its fruit and essential oil. It is mostly grown in Java and Sumatra, hence sometimes called Java pepper. The fruits are gathered before they are ripe, and carefully dried. Commercial cubeb consists of the dried berries, similar in appearance to black pepper, but with stalks attached – the "tails" in "tailed pepper". The dried pericarp is wrinkled, and its color ranges from grayish brown to black. The seed is hard, white and oily. The odor of cubeb is described as agreeable and aromatic and the taste as pungent, acrid, slightly bitter and persistent. It has been described as tasting like allspice, or like a cross between allspice and black pepper.[1]

Cubeb came to Europe via India through the trade with the Arabs. The name cubeb comes from Arabic Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (كبابة)[2] by way of Old French quibibes.[3] Cubeb is mentioned in alchemical writings by its Arabic name. In his Theatrum Botanicum, John Parkinson tells that the king of Portugal (Possibly either Philip IV of Spain or John IV of Portugal, as that year was marked by the start of the Portuguese Restoration War) prohibited the sale of cubeb to promote black pepper (Piper nigrum) around 1640. It experienced a brief resurgence in 19th-century Europe for medicinal uses, but has practically vanished from the European market since. It continues to be used as a flavoring agent for gins and cigarettes in the West, and as a seasoning for food in Indonesia.

History

In the fourth century BC, Theophrastus mentioned komakon, including it with cinnamon and cassia as an ingredient in aromatic confections. Guillaume Budé and Claudius Salmasius have identified komakon with cubeb, probably due to the resemblance which the word bears to the Javanese name of cubeb, kumukus. This is seen as a curious evidence of Greek trade with Java in a time earlier than that of Theophrastus.[4] It is unlikely Greeks acquired them from somewhere else, since Javanese growers protected their monopoly of the trade by sterilizing the berries by scalding, ensuring that the vines were unable to be cultivated elsewhere.[2]

In the Tang dynasty, cubeb was brought to China from Srivijaya. In India, the spice came to be called kabab chini, that is, "Chinese cubeb", possibly because the Chinese had a hand in its trade, but more likely because it was an important item in the trade with China. In China, this pepper was called both vilenga and viḍaṅga विडङ्ग (the cognate Sanskrit word), which had denoted embelia ribes before being used to denote the Malayan cubeb (simplified Chinese: 荜澄茄; traditional Chinese: 蓽澄茄; pinyin: bì chéng qié[5]).[6][7] Li Hsun thought it grew on the same tree as black pepper. Tang physicians administered it to restore appetite, cure "demon vapors", darken the hair, and perfume the body. However, there is no evidence showing that cubeb was used as a condiment in China.[6]

In his 1827 dictionary Nhật dụng thường đàm (vi) (日用常談; Template:Literal), Vietnamese scholar-official Phạm Đình Hổ (vi) glossed 蓽䔲茄 "cubeb" (Sino-Vietnamese: tất đăng gia) as 乙 ớt, which currently denotes chilli pepper from the Americas.[8][9]

The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, compiled in the 9th century, mentions cubeb as a remedy for infertility, showing it was already used by Arabs for medicinal purposes. Cubeb was introduced to Arabic cuisine around the 10th century.[10] The Travels of Marco Polo, written in late 13th century, describes Java as a producer of cubeb, along with other valuable spices.[11]

In the 14th century, cubeb was imported into Europe from the Grain Coast, under the name of pepper, by merchants of Rouen and Lippe.[1] Cubeb eventually came to be thought of as repulsive to demons by the people of Europe. Ludovico Maria Sinistrari, a Catholic priest who wrote about methods of exorcism in the late 17th century, includes cubeb as an ingredient in an incense to ward off an incubus.[12]

After the prohibition of its sale in Portugal in 1640, culinary use of cubeb decreased dramatically in Europe, and only its medicinal application continued to the 19th century. In the early 20th century, cubeb was regularly shipped from Indonesia to Europe and the United States. The trade gradually diminished to an average of 135 t (133 long tons; 149 short tons) annually, and practically ceased after 1940.[13]

Chemistry

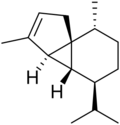

The dried cubeb berries contain essential oil comprising monoterpenes (sabinene 50%, α-thujene, and carene) and sesquiterpenes (caryophyllene, copaene, α- and β-cubebene, δ-cadinene, germacrene), the oxides 1,4- and 1,8-cineole and the alcohol cubebol.

About 15% of a volatile oil is obtained by distilling cubeb with water. Cubebene, the liquid portion, has the formula[1] C15H24 and comes in two forms, α- and β-. They differ only in the position of the alkene moiety, with the double-bond being endocyclic (part of the five-membered ring) in α-cubebene, as shown, but exocyclic in β-cubebene. It is a pale green viscous liquid with a warm woody, slightly camphoraceous odor.[14] After rectification with water, or on keeping, this deposits rhombic crystals of camphor of cubeb.[1]

Cubebin (C20H20O6)[15] is a crystalline organic compound isolated from cubeb oilcake, and can be chemically synthesized from cubebene. It was discovered by Eugène Soubeiran and Hyacinthe Capitaine in 1839, and irritates the mucus membranes.[1]

Uses

History in folk medicine

Iatroalchemists in the Islamic Golden Age distilled "water of al butm" (turpentine) from a mixture of herbal products, including cubeb.[16]

In Victorian and Edwardian England, cubeb was an antiseptic for gonorrhea treatment.[1] William Wyatt Squire wrote in 1908 that cubeb berries "act specifically on the genitourinary mucous membrane. (They are) given in all stages of gonorrhea"[17] and The National Botanic Pharmacopoeia printed in 1921 stated that cubeb was "an excellent remedy for flour albus or whites".[18] A tincture of the compound appeared in the British Pharmacopoeia, and a gum with 1% cubebin, roughly equivalent to 30-60 grains of cubeb fruit, had become standardized as a drug, also called cubeb.[1]

Culinary

In Europe, cubeb was one of the valuable spices during the Middle Ages. It was ground as a seasoning for meat or used in sauces.[1] A medieval recipe includes cubeb in making sauce sarcenes, which consists of almond milk and several spices.[19] As an aromatic confectionery, cubeb was often candied and eaten whole.[20] Ocet Kubebowy, a vinegar infused with cubeb, cumin and garlic, was used for meat marinades in Poland during the 14th century (Dembinska 1999). Cubeb can be used to enhance the flavor of savory soups.

Cubeb reached Africa by way of the Arabs. In Moroccan cuisine, cubeb is used in savory dishes and in pastries like makrouts, little diamonds of semolina with honey and dates.[10] It also appears occasionally in the list of ingredients for the famed spice mixture Ras el hanout. In Indonesian cuisine, especially in Indonesian gulés (curries), cubeb is frequently used.

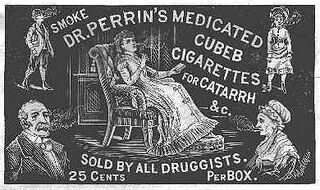

Cigarettes and spirits

Cubeb was frequently used in the form of cigarettes for asthma, chronic pharyngitis, and hay fever.[1] Edgar Rice Burroughs, being fond of smoking cubeb cigarettes, humorously stated that if he had not smoked so many cubebs, there might never have been Tarzan. Marshall's Prepared Cubeb Cigarettes was a popular brand, with enough sales to still be made during World War II.[21]

In 2000, cubeb oil was included in the list of ingredients found in cigarettes, published by the Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch of North Carolina's Department of Health and Human Services.[22]

Bombay Sapphire gin is flavored with botanicals including cubeb and grains of paradise. The brand was launched in 1987, but its maker claims that it is based on a secret recipe dating to 1761. Pertsivka, a dark brown Ukrainian pepper flavoured horilka with a burning taste, is prepared from infusion of cubeb and capsicum peppers.[23]

Other

Cubeb is sometimes used to adulterate the essential oil of patchouli, which requires caution for patchouli users.[24] In turn, cubeb is adulterated by Piper baccatum (also known as the "climbing pepper of Java") and Piper caninum.[25]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Chisholm 1911, p. 607.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 (Katzer 1998)

- ↑ (Hess 1996)

- ↑ (Cordier Yule) Chapter XXV.

- ↑ Wiseman, Nigel (2022) Chinese-English Dictionary of Chinese Medical Terms. link to unnumbered page

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (Schafer 1985)

- ↑ "विडङ्ग viḍaṅga". https://sanskrit.inria.fr/DICO/59.html#vi.dafga. "m. bio. bot. Embelia Ribes, arbuste primulacée, aux fruits rouge-noirs ; c'est une plante médicinale importante — n. son fruit, employé comme vermifuge."

- ↑ Phạm Đình Hổ (author) (1827), 日用常談 (Nhật dụng thường đàm "Common Words Used Daily"); textually studied and transliterated by Lê Văn Cường. entry "ớt": Hán-Nôm text: (蓽䔲茄羅乙); Quốc Ngữ: "tất đăng gia là ớt". Giáp Thị Hải Chi's English gloss: "chilli"; p. 29 of 121, 3rd column from right.

- ↑ "ớt". https://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/~duc/TD/td/index.php?word=%E1%BB%9Bt&db=ve.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 (Hal 2002)

- ↑ "Mongols in World History | Asia for Educators". http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/pop/menu/class_marco.htm.

- ↑ (Sinistrari 2003). "...Incubus none the less persisted in appearing to her constantly, in the shape of an exceptionally handsome young man. At last, among other learned men, whose advice had been taken on the subject, was a very profound Theologian who, observing that the maiden was of a thoroughly phlegmatic temperament, surmised that that Incubus was an aqueous Demon (there are in fact, as is testified by Guazzo (Compendium Maleficarum, I. 19), igneous, aerial, phlegmatic, earthly, and subterranean demons who avoid the light of day), and so he prescribed a continual suffumigation in the room. A new vessel, made of earthenware and glass, was accordingly introduced, and filled with sweet calamus, cubeb seed, roots of both aristolochies, great and small cardamom, ginger, long-pepper, caryophylleae, cinnamon, cloves, mace, nutmegs, calamite storax, benzoin, aloes-wood and roots, one ounce of fragrant sandal, and three quarts of half brandy and water; the vessel was then set on hot ashes in order to force forth and upwards the fumigating vapour, and the cell was kept closed. As soon as the suffumigation was done, the Incubus came, but never dared enter the cell."

- ↑ (Weiss 2002).

- ↑ (Lawless 1995)

- ↑ "Cubebin Compound Summary - PubChem - NCBI". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/117443.

- ↑ Patai 1995, p. 315.

- ↑ Squire 1908, p. 462.

- ↑ Scurrah 1921, p. 34.

- ↑ (Hieatt 1988) "Make a thykke mylke of almondys, do hit in a pot with floure of rys, safron, gynger, macys, quibibis, canel, sygure: and rynse the bottom of the disch with fat broth. Boyle the sewe byfore, and messe hit forth."

- ↑ Candied cubeb is mentioned in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow, set in the 1940s: "Under its tamarind glaze, the Mills bomb turns out to be luscious pepsin-flavored nougat, chock-full of tangy candied cubeb berries, and a chewy camphor-gum center. It is unspeakably awful. Slothrop's head begins to reel with camphor fumes, his eyes are running, his tongue's a hopeless holocaust. Cubeb? He used to smoke that stuff." (Pynchon 1973)

- ↑ (Shaw 1998).

- ↑ "Cigarette Ingredients". Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. http://www.stepupnc.com/know/ingredients.shtm.

- ↑ (Grossman 1983)

- ↑ (Long 2002)

- ↑ (Seidemann 2005)

Works cited

- Adams, E. (1847), The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta, translated from Greek, Vol.3, London: The Sydenham Society.

- Cordier, Henri; Yule, Henry (1920), "The Travels of Marco Polo, Volume 2 by Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa", The Travels of Marco Polo, http://www.fullbooks.com/The-Travels-of-Marco-Polo-Volume-210.html, "January 9, 2006,".

- Culpeper, Nicholas (1654), Pharmacopoeia Londoninsis: or The London Dispensatorie, London: Peter Cole.

- Davidson, Alan (1999), The Oxford Companion to Food, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9, https://archive.org/details/oxfordcompaniont00davi_0.

- Dembinska, Maria (1999), Food and Drink in Medieval Poland, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-3224-0.

- Grossman, Harold J. (1983), Grossman's Guide to Wines, Beers, and Spirits, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-684-17772-4, https://archive.org/details/grossmansguideto0000gros_c0c4.

- Hal, Fatema (2002), The Food of Morocco: Authentic Recipes from the North African Coast, Periplus, ISBN 978-962-593-992-6.

- Harris, Jessica B. (1998), The Africa Cookbook, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-684-80275-6, https://archive.org/details/africacookbookta0000harr.

- Hess, Karen (1996), Martha Washington's Booke of Cookery and Booke of Sweetmeats, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-04931-3.

- Hieatt, Constance B., ed. (1988), An Ordinance of Pottage, Prospect Books, ISBN 978-0-907325-38-3.

- Katzer, Gernot (April 25, 1998), "Cubeb pepper (Cubebs, Piper cubeba)", Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages, http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com/engl/Pipe_cub.html.

- Khare, C.P. (2004), Indian Herbal Remedies: Rational Western Therapy, Ayurvedic and Other Traditional Usage, Botany, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-01026-5.

- Lawless, Julia (1995), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Essential Oils: The Complete Guide to the Use of Oils in Aromatherapy and Herbalism, Element Books, ISBN 978-1-85230-721-9.

- Long, Jill M. (2002), Permission to Nap: Taking Time to Restore Your Spirit, Sourcebooks, ISBN 978-1-57071-938-7.

- Mathers, E.P. (1990), The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (Vol. 2), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-04540-7.

- Patai, Raphael (1995), The Jewish Alchemists, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00642-0.

- Pynchon, Thomas (1973), Gravity's Rainbow, Penguin Classics (1995 reprint edition), ISBN 978-0-14-018859-2.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'Ang Exotics, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Scurrah, J. W. (1921), The National Botanic Pharmacopoeia, 2nd Ed., Bradford: Woodhouse, Cornthwaite & Co..

- Seidemann, Johannes (2005), World Spice Plants: Economic Usage, Botany, Taxonomy, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-22279-8.

- Shaw, James A. (January 1998), "Marshall's Cubeb", Jim's Burnt Offerings, http://www.wclynx.com/burntofferings/packscubeb.html, retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Sinistrari, Ludovico M. (2003), Demoniality, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7661-4251-0.

- Sloman, Larry (1998), Reefer Madness: A History of Marijuana, St. Martin's Griffin, ISBN 978-0-312-19523-6, https://archive.org/details/reefermadnesshis0000slom.

- Stearns, Cyrus (2000), Hermit of Go Cliffs - Timeless Instructions of a Tibetan Mystic, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-164-2.

- Squire, W. (1908), Squire's Companion to the latest edition of the British Pharmacopoeia, 18th ed., London: J. and A. Churchill.

- Weiss, E. A. (2002), Spice Crops, CABI Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85199-605-9.

Attribution

Template:African cuisine Wikidata ☰ Q161927 entry

|