Social:Communist state

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

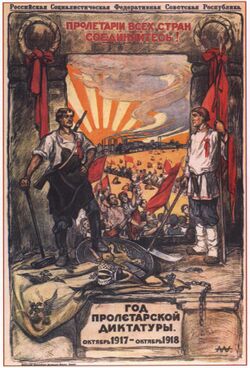

A communist state is a form of government that combines the state leadership of a communist party, Marxist–Leninist political philosophy, and an official commitment to the construction of a communist society. Communism in its modern form grew out of the socialist movement in 19th-century Europe and blamed capitalism for societal miseries. In the 20th century, several communist states were established, first in Russia with the Russian Revolution of 1917 and then in portions of Eastern Europe, Asia, and a few other regions after World War II. The institutions of these states were heavily influenced by the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin and others. During most of the 20th century, around one-third of the world's population lived in communist states.[1] However, the political reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev known as Perestroika and socio-economic difficulties produced the revolutions of 1989, which brought down all the communist states of the Eastern Bloc bar the Soviet Union. The repercussions of the collapse of these states contributed to political transformations in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia and several other non-European communist states. Presently, there are five communist states in the world: China , Cuba, Laos, North Korea and Vietnam.

In accordance with Marx's theory of the state, communists believe all state formations are under the control of a ruling class. Communist states are no different, and the ruling communist party is defined as the vanguard party of the most class conscious section of the working class (this class is known as the proletariat in Marxist literature). Communist states usually affirm that the working class is the state's ruling class and that the most class-conscious workers lead the state through the communist party, establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat as its class system and, by extension, the socialist state. However, not all communist states chose to form this class system, and some, such as Laos, have opted to establish a people's democratic state instead, in which the working class shares political power with other classes. According to this belief system, communist states need to establish an economic base to support the ruling class system (called "superstructure" by Marxists) by creating a socialist economy, or at the very least, some socialist property relations that are strong enough to support the communist class system. By ensuring these two features, the communist party seeks to make Marxism–Leninism the guiding ideology of the state. Normally, the constitution of a communist state defines the class system, economic system and guiding ideology of the state.

The political systems of these states are based on the principles of democratic centralism and unified power. Democratic centralism seeks to centralise powers in the highest leadership and, in theory, reach political decisions through democratic processes. Unified power is the opposite of the separation of powers and seeks to turn the national representative organ elected through non-competitive, controlled elections into the state's single branch of government. This institution is commonly called the highest organ of state power, and a ruling communist party normally holds at least two-thirds of the seats in this body. The highest organ of state power has unlimited powers bar the limits it has itself set by adopting constitutional and legal documents. What would be considered executive or judicial branches in a liberal democratic system are in communist states deemed as bodies of the highest organ of state power. The highest organ of state power usually adopts a constitution that explicitly gives the ruling communist party leadership of the state.

The communist party controls the highest organ of state power through the political discipline it exerts on its members and, through them, dominates the state. Ruling communist parties of these states are organised on Leninist lines, in which the party congress functions as its supreme decision-making body. In between two congresses, the central committee acts as the highest organ. When neither the party congress nor the central committee is in session, the decision-making authorities of these organs are normally delegated to its politburo, which makes political decisions, and a secretariat, which executes the decisions made by the party congress, central committee and the politburo. These bodies are composed of leading figures from state and party organs. The leaders of these parties are often given the title of general secretary, but the power of this office varies from state to state. Some states are characterised by one-man dominance and the cult of personality, while others are run by a collective leadership, a system in which powers are more evenly distributed between leading officials and decision-making organs are more institutionalised.

These states seek to mobilise the public to participate in state affairs by implementing the transmission belt principle, meaning that the communist party seeks to maintain close contact with the masses through mass organisations and other institutions that try to encompass everyone and not only committed communists. Other methods are through coercion and political campaigns. Some have criticised these methods as dictatorial since the communist party remains the centre of power. Others emphasise that these are examples of communist states with functioning political participation processes (i.e. Soviet democracy) involving several other non-party organisations such as direct democratic participation, factory committees, and trade unions.[2][3][4]

Etymology

No communist state has ever called itself such, and according to David Ramsay Steele, the term "communist state" is an invention of foreign observers: "Among Western journalists, the term 'Communist' came to refer exclusively to regimes and movements associated with the Communist International and its offspring: regimes which insisted that they were not communist but socialist, and movements which were barely communist in any sense at all."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) These states commonly describe themselves as socialist states since they do not claim to have achieved communism, as it would constitute an oxymoron—communist society is anticipated to be stateless. Scholar Jozef Wilczynski notes: "Contrary to Western usage, these countries describe themselves as 'Socialist' (not 'Communist'). The second stage (Marx's 'higher phase'), or 'Communism', is to be marked by an age of plenty, distribution according to needs (not work), the absence of money and the market mechanism, the disappearance of the last vestiges of capitalism and the ultimate 'whithering away' of the State."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Scholars John Barkley and Marina Rosser concur and note: "Ironically, the ideological father of communism, Karl Marx, claimed that communism entailed the withering away of the state. The dictatorship of the proletariat was to be a strictly temporary phenomenon. Well aware of this, the Soviet Communists never claimed to have achieved communism, always labeling their own system socialist rather than communist and viewing their system as in transition to communism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Academic Raymond Williams notes that etymologically this naming convention is due to a name change: "The decisive distinction between socialist and communist, as in one sense these terms are now ordinarily used, came with the renaming, in 1918, of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) as the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). From that time on, a distinction of socialist from communist, often with supporting definitions such as social democrat or democratic socialist, became widely current, although it is significant that all communist parties, in line with earlier usage, continued to describe themselves as socialist and dedicated to socialism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Other self-descriptions used by communist states are, for example, national-democratic, people's democratic, socialist-oriented, and workers and peasants' states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

From a Western political science perspective, it is correct to speak of a communist state since these states share several characteristics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) According to scholars Stephen White, John Gardner and George Schöpflin these states share four defining features. The first defining feature is that every communist state has Marxism–Leninism as its official ideology. They note that this does not mean that every leader of these states is committed to Marxist values, stating that this is a separate and empirical question. The second feature is that the whole economy, or large parts, is state-owned and organised, most commonly through a centrally-planned state apparatus. The third feature is the one-party system of a single communist party and, in some exceptional circumstances, a system in which other parties exist but the communist party is dominant. This party is highly centralised and disciplined. The last defining feature, according to White, Gardner and Schöpflin, is the control the communist party has over society, which is often constitutionally stipulated by giving the party the leading role in state and society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Governing principles

Class system

In Marxist–Leninist thought, the state is a repressive institution led by a ruling class that uses it to implement its class dictatorship. In a communist state, the communist party seeks to establish and organise a class dictatorship, such as the dictatorship of the proletariat on behalf of the proletariat (Marxist term for the working class) for example.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) States that practice this class system are categorised, according to Marxist–Leninist thought, as socialist states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This dictatorship is led by the communist party, which acts as vanguard of the most class-conscious section of the working class (this class is known as the proletariat in Marxist literature). This vanguard acts as the state's ruling class and seeks to lead the state, the working class and other social classes in its efforts to construct socialism, abolish class society and establish a communist society. These goals were made clear in the preamble of the 1918 Constitution of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), "The principal object of the Constitution of the R.S.F.S.R., which is adapted to the present transition period, consists in the establishment of a dictatorship of the urban and rural proletariat and the poorest peasantry, in the form of a powerful All-Russian Soviet power; the object of which is to secure complete suppression of the bourgeoisie, the abolition of exploitation of man by man, and the establishment of Socialism, under which there shall be neither class division nor state authority".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The communist class system is institutionalised in law by giving the communist party the status as the leading force of state and society (see "Leading role of the party" section).({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The class system of socialist states can also, according to Soviet Marxist-Leninists, develop from the proletarian dictatorship into a socialist state of the whole people (also known as the all-people's state). The programme of the CPSU, adopted by the 22nd Congress in 1961, said that the dictatorship of the proletariat "has fulfilled its historic mission and is no longer essential in terms of current objectives involving the country's further progress" and, "The state based at its inception on the dictatorship of the proletariat has now evolved into an all-people's state."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Khrushchev also reasoned that this development was proof that "Socialism has won a complete and final victory in our country, and we have now entered the stage of sweeping construction of communism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In this class system, there was no need for a proletarian dictatorship since all non-antagonistic classes had ceased to exist, and the remaining ones were friendly towards the Marxist–Leninist project.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It was also believed that the exploiting classes had ceased to exist in the Soviet Union.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Despite this, the proletariat was still considered the leading class in society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, the idea that the dictatorship of the proletariat had ceased to exist before the withering away of the state proved controversial since it broke with the Marxist conception of a ruling class—the state only exists as a tool for class domination.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The theoretical newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) deemed Khrushchev to be a revisionist: "a more dangerous enemy of Communist unity than rebels such as [Josep Broz] Tito of Yugoslavia and Leon Trotsky".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Despite criticism from within the communist movement, the 1977 Constitution stated that the Soviet Union was a socialist state of the whole people that led the working masses, peasants and intelligentsia under the leadership of the working class in their bid to construct a communist society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It also made clear that the state of the whole people could only emerge during and was the class system of the stage of developed socialism.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

According to Marxist–Leninists, other communist class systems exist. For instance, Klement Gottwald, the chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and later president of Czechoslovakia, stated on 4 October 1946, "that there exists another path to socialism than by way of a dictatorship of the proletariat and the soviet state system. Going by this path are Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Poland, and also Czechoslovakia."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This class system was termed people's democracy and seized power through a people's democratic revolution, such as the national democratic revolution in Czechoslovakia, the democratic revolution in Hungary and the new democratic revolution in China.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) A people's democratic state is established in communist states that have not yet developed socialism.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) As such, the people's democratic state is a revolutionary democracy that was transforming the country from a people's democratic state into a socialist state under the dictatorship of the proletariat. The class system was called the democratic dictatorship, in which the working class formed and led an alliance of the peasantry, the petite bourgeoisie, and part of the national bourgeoisie.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Socialism was reached when the working class strengthened its own class power by removing representatives of the bourgeoisie classes from positions of power.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This broad popular alliance is what distinguishes the people's democratic revolution from a socialist revolution. However, in both cases, the working class leads through a Marxist–Leninist vanguard party.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Georgi Dimitrov, who served as general secretary of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (Comintern) and later as general secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, argued that the people's democratic state through its democratic dictatorship was a form of proletarian dictatorship.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In Czechoslovakia's case, this meant, according to Gottwald, that the working class "governs, along with the mass of the peasantry, the urban middle classes, the working intelligentsia and a part of the Czech and Slovak bourgeoisie; the government's direction, the government's line of policy, is therefore determined, not by large capital as earlier, but by the working class and the working people, headed by the Communist Party."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Currently, Laos is the only communist state that practices this class system. Its constitution states that its a people's democratic state where "all powers are of the people, by the people and for the interests of the multi-ethnic people of all strata in society, with workers, farmers, and intellectuals as key components."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

According to the CCP, communists must implement the proletarian dictatorship to fit their national circumstances, and China's implementation of it is known as the people's democratic dictatorship. Wang Weiguang, President of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences from 2013 to 2018, states, "The people's democratic dictatorship is the dictatorship of the proletariat with Chinese characteristics."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The people's democratic dictatorship should be understood as a form of people's democracy that encompasses, according to Marxist–Leninist thinking, the broadest number of people possible. However, the working class remains the leading class of the CCP and the state, which rules through an alliance with the peasant class. Wang notes, "A state under the people's democratic dictatorship practices democracy among the people and exercises dictatorship over the enemies of the people, and these two aspects are inseparable. The people's democratic dictatorship is the dialectical unity of dictatorship and democracy."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

After Joseph Stalin 's death in 1953, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) began re-evaluating its theoretical outlook on the underdeveloped countries of Asia and Africa.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) With the collapse of the colonial system and the establishment of new independent states, the CPSU under Nikita Khrushchev's leadership began to give particular attention to the Third World. There was a general sense of optimism in the Soviet Union that the newly independent states were potential joint anti-imperialist partners in the struggle against the capitalist powers.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) At the 1960 International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties, the gathered parties introduced the concept of the new democratic state.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The concept borrowed heavily from Vladimir Lenin's speech to the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in 1920, in which he remarked on the possibility of colonised and newly liberated colonies of partaking in non-capitalist development.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) According to Soviet Marxist–Leninists, the new democratic state had three key features: first, it had an anti-imperialist policy; second, it initiated a policy of economic independence; and lastly, it gave communists the right to organise freely.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) While the 1960 meeting noted that the "alliance of the working class and peasantry" was the most important force in the national liberation movement and in the new democratic state, the CPSU later noted that the new democratic revolution encompassed "support from all persons at all levels of society, as long as they opposed imperialism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The 22nd CPSU Congress in 1961 further defined the class system of the new democratic state, noting that the national bourgeoisie had to share power with other classes in such state formations. The task of communists in these states was to support them.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, the end-result was mixed. Most of the new democratic states, such as the United Arab Republic and Algeria, oppressed their communist parties. At the same time, many of the designated new democratic states were more radical in their economic policy than what Soviet Marxist–Leninists conceived as possible. This made Khrushchev conclude that "today practically any country, irrespective of its level of development, can enter on the road leading to Socialism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, with the removal from power of socialist radicals in Algeria (Ben Bella), Mali (Modibo Keïta) and Ghana (Kwame Nkrumah), Soviet Marxist–Leninist began calling for a reassessment of the class characters of these states. They eventually conceived of a new concept, state of socialist orientation.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

States of socialist orientation were divided into two categories by Soviet Marxist–Leninists: the national democratic state of socialist orientation and the people's democratic state of socialist orientation. The national democratic state of socialist orientation was similar to the old new democratic state, with the working class not having control of the state. Moreover, it was not expected that the national democratic states would introduce the political systems that existed in the socialist states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In people's democratic states of socialist orientation, a revolutionary vanguard that professed belief in Marxism–Leninism had taken power.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Another feature was, according to CPSU Central Committee apparatus cadre Karen Brutents, was alignment in foreign policy with the existing socialist states: "The cornerstone of socialist orientation is naturally the direction of domestic development. But experience has shown that a progressive, anti-imperialist foreign policy is also an essential component. These two aspects are organically linked ... Socialist-orientation is impossible without close friendship and cooperation with the socialist world".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The revolutionary vanguard party in a people's democratic state of socialist orientation was expected to monopolise political power on behalf of labouring classes and strengthen the proletarian dictatorship. The party was expected to nationalise the commanding heights of the economy, protect the state-owned economy, eliminate foreign monopolies, support cooperatives and limit the growth of private capital.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) As such, it was expected that a state of socialist orientation was to run a mixed economy.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It was not expected of a people's democratic state of socialist orientation that it would have an identical system with that of the existing socialist state community. Still, states of socialist orientation that had established a highest organ of state power based on the principle of unified power were deemed the most advanced.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Democratic centralism

The concept of democratic centralism was conceived by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Lenin argued that democratic centralism entailed the "dialectical unity" of democracy (freedom) and centralism (authority).({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Democratic centralism postulates that decisions must be made through free and open debate (freedom). When the debate has reached a decision, it is binding on all participants, and everyone, even those opposing it, has to implement it uniformly (centralism).({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It was first adopted as the organisational principle of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party at the Tampere conference of 1905. The resolution defined the term as follows: "Recognising that the principle of democratic centralism is beyond dispute, the conference regards it as essential to establish a broad electoral principle whilst allowing the elected central bodies full power in ideological and practical leadership, together with their revocability and with the widest publicity and strictest accountability of their actions."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, the concept was never considered to be exclusive to the party alone. In 1913, Lenin called for implementing it in the state as well, "democratic centralism not only does not exclude local self-government, with autonomy of regions which are distinct in terms of special economic conditions and way of life, of a particular national make-up of the population, and so on, on the contrary, it insistently demands both the one and the other."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), held on 8–16 March 1921, reaffirmed democratic centralism by banning all factions within the Party.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) While the ban on faction was adopted as a temporary measure, it became a formal rule that, in some cases, outlawed the very notion of an opposition within party ranks.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This notion eventually developed into the definition adopted by the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in 1934. The ruling parties of all other communist states have had similar provisions in their statute.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Soviet party definition, which remained unchanged for most of its existence, stated;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All bodies, from the lowest to the highest level, were electable;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All bodies had to report and were held accountable by their respective party organisation;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All members were required to work under party discipline and abide by majority decisions;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All decisions made by the highest bodies were binding on lower-level bodies and members.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The 2nd World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern), an organisation tasked with leading the international communist movement, in 1920 adopted the document, "Conditions of Admission to the Communist International". It stated that parties had to adopt democratic centralism as their organisational principle to be admitted into the Comintern: "Parties belonging to the Communist International must be structured according to the principle of democratic centralism. In the present epoch of sharpened civil war, a communist party can carry out its duty only if it is organised in the most centralised way, if iron discipline bordering on military discipline reigns in it, and if its party centre is a powerful, authoritative organ with the widest competences, and enjoys the general trust of the party."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The emphasise was put on the centralism in democratic centralism, with the Comintern stating it meant "iron discipline, bordering on military discipline".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, the same congress also defined "the main principle of democratic centralism" as "the higher cell being elected by the lower cell, the absolute binding force of all directions of a higher cell for a cell subordinate to it, and the existence of a commanding party centre undisputed for all leaders in party life."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

As an organisational principle of the state, it encompassed both state institutions and economic policy more generally.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) For instance, the Hungarian Marxist textbook from 1963, Textbook of Political Economy, stated, "The planned direction of the economy is based on the Leninist principle of democratic centralism. This principle involves a combination of the planned, central direction of economic activities with the greatest development of the creative activity of the working masses".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, those championing non-state cooperatives in Hungary believed democratic centralism would harm their economic freedom. Rezső Nyers, the Central Committee Secretary for Economic Policy of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, argued in 1956 that the principle was necessary in light of more radical economic reforms, "Democratic centralism is the principle of the direction of the socialist economy, whichever precise type of the planned economy is involved. ... In the case of the cooperatives, democratic centralism is valid even when these are self-governing. What is more, the principle is valid even as regards the relationship of the cooperatives and the central organs of cooperatives."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) To put an end to the debate, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences formed a working committee tasked with formulating a precise meaning of the term democratic centralism. The committee concluded that democratic centralism was not applicable to economic management, and that the term itself encompassed four components:({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All leading organs were electable;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All leading organs had to report on and be held accountable for their work;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All officials were under strict discipline, and the minority had to accept and enforce majority decisions;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All decisions made by higher organs were mandatory on lower-level organs.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Democratic centralism was also the organisational principle of every communist state in existence in one form or another.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In the Soviet Union, democratic centralism in the state was defined as follows:({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All state officials can be recalled;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All lower-level organs of state power are subordinate to and must report to higher organs of state power;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All working organs are subordinate to the relevant organ of state power;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All decisions made by higher organs of state power were binding on the lower ones;({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

- All decisions of the highest organ of state power, which is the highest body of the state, are binding on the state as a whole.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Economic relations and stage theory

Marxism–Leninism holds that the relations of production in a given society are dictated by the level and the nature of the material productive forces, that is, how people work and the level of technological development of that given society. They hold, similar to classical Marxism, that the first modes of production, the first economic system and the society it produced, was primitive communism, a society where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group per individual needs. With technological progress and the ensuing changes in labour relations, a mode of production based on slavery was created, which lasted until the feudal mode of production, in which the aristocracy acted as the state's ruling class based on their control of arable land.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Feudalism grew into the capitalist mode of production based on private property with capitalists as the ruling class. Marxist–Leninists argue that the capitalist mode of production will be replaced by the socialist mode of production (also called socialism and the first stage of communism), which will develop into the communist mode of production under the communist party's leadership. To start the construction of socialism, the proletariat needs to take power in a socialist revolution.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Every communist state seeks to establish, develop into and further construct socialism so as to establish a communist society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, ruling communist states have interpreted what stage their state (and other communist states) is in differently and have chosen different strategies to construct socialism.

From reading their works, many followers of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels drew the idea that the socialist economy would be based on planning and not market mechanisms.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) These ideas later developed into believing that planning was superior to the market mechanism.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Upon seizing power, the Bolsheviks began advocating a national state planning system.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) resolved to institute "the maximum centralisation of production [...] simultaneously striving to establish a unified economic plan."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Gosplan, the State Planning Commission, the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy, and other central planning organs were established during the 1920s in the era of the New Economic Policy.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) On introducing the planning system, it became a common belief in the international communist movement that the Soviet planning system was a more advanced form of economic organisation than capitalism.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This led to the system being introduced voluntarily in countries such as China, Cuba, and Vietnam and, in some cases, imposed by the Soviet Union.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

In communist states, the state planning system had five main characteristics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Firstly, except for field consumption and employment, practically all decisions were centralized at the top.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Secondly, the system was hierarchical—the centre formulated a plan that was sent down to the level below, which would imitate the process and send the plan further down the pyramid.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Thirdly, the plans were binding in nature, i.e. everyone had to follow and meet the goals outlined in them.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Fourthly, the predominance of calculating in physical terms to ensure planned allocation of commodities were not incompatible with planned production.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Finally, money played a passive role within the state sector since the planners focused on physical allocation.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

According to Michael Ellman, in a centrally-planned economy, "the state owns the land and all other natural resources and all characteristics of the traditional model, the enterprises, and their productive assets. Collective ownership (e.g. the property of collective farms) also exists but plays a subsidiary role and is expected to be temporary."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The private ownership of the means of production still exists, although it plays a somewhat more minor role.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Since the class struggle in capitalism is caused by the division between owners of the means of production and the workers who sell their labour, state ownership (defined as the property of the people in these systems) is considered as a tool to end the class struggle and empower the working class.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Leading role of the party

A defining feature of the communist form of government is the communist party's monopolisation of state power.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) A party with ideological allegiance to Marxism–Leninism party has led every communist state.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) From the 1960s onwards, communist states began using the term "the leading role of the party" to describe the role of the communist party in their political systems.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Soviet Union was the first to formalise this principle into law, doing so in the 1977 Soviet Constitution. Article 6 stated, "The leading and guiding force of Soviet society and the nucleus of its political system, of all state organisations and public organisations, is the Communist Party of the Soviet Union."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) According to scholar Archie Brown, "By the beginning of the 1980s variants of the concept of the 'leading role of the party' appeared in the constitutions of all consolidated Communist states, including Vietnam, where the whole country had been Communist only since 1976."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) For example, the constitution of the Mongolian People's Republic stated, "In the Mongolian People's Republic, the guiding and directing force of society and of the state is the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party, which is guided in its activities by the all-conquering theory of Marxism–Leninism."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In some communist states, such as China, this was done much later. China added a similar statement in 2018: "Leadership by the Communist Party of China is the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Unified power through the highest organ of state power

Every communist state is based on the principle of unified power, in which all powers are vested in the highest organ of state power.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The institutional design was conceived by Vladimir Lenin, but he was inspired Karl Marx's views on democracy and his pamphlet, The Civil War in France.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In that book, Marx wrote very positively of the political system established by the Paris Commune, which he called the "the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of Labour".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Marx embraced the Commune's system of popular delegacy rather than traditional representative democracy, the electors right to recall their elected representatives, the representative's short electoral mandates and its opposition to the separation of powers.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) He termed the Commune as a Social Republic (but also interchangeably referred to as the "red Republic" and the "Republic of Labour)", and defined it as follows: "a Republic which disowns the capital and landowner class of the State machinery to supersede it by the Commune, that frankly avows ‘social emancipation’ as the great goal of the Republic and guarantees thus that social transformation by the Communal organisation."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Commune was perceived by Marx as the first example of proletarian rule that had the ability to overcome the division between a private and a political sphere in society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Marx further criticised liberal representative democracy of serving the ruling class, "[i]nstead of deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to misrepresent the people in Parliament, universal suffrage was to serve the people, constituted in Communes."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The Commune, through its representative body, the Commune Council, had both executive and legislative powers while also having the right to interfere in the judiciary. Marx wrote approvingly of this model, noting that it was "a working, not a parliamentary, body, executive and legislative at the same time."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Similarly, he criticised the liberal principle of "separation of powers is the first principle of a free government", stating, "Here we have the old constitutional folly. The condition of a 'free government' is not the division, but the UNITY of power. The machinery of government cannot be too simple. It is always the craft of knaves to make it complicated and mysterious."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In its bid to institutionalise unity of power, the Council established ten internal commissions that were given responsibility for government affairs. These commissions comprised two-thirds of the council members. This is why Marx and later Lenin referred to them as working bodies. The logic of this system was that there were no executive functions separate from the legislature.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Lenin shared Marx's distaste for parliamentarism, arguing that "Marxism differs from the petty-bourgeois, opportunist “Social-Democratism” of [Georgy] Plekhanov, [Karl] Kautsky and Co. in that it recognises that what is required during these two periods is not a state of the usual parliamentary bourgeois republican type, but a state of the Paris Commune type."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) He believed a parliamentary system hampered the political participation of the masses and stifled independent political life.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Before and during the Russian revolution of 1917, Lenin agitated for a republic of soviets, a democracy which he believed mirrored that of the Paris Commune, under the slogan "All power to the Soviets!"({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The soviets, Lenin remarked, were not to be parliamentary bodies: "Representative institutions remain, but there is no parliamentarism here as a special system, as the division of labour between the legislative and the executive, as a privileged position for the deputies."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Soviet legal theorists embraced the idea of "the supremacy of the elected representative assembly in the Soviet State" and that the highest organ of state power had complete state power; "All other activities of the State are subordinate in character [to the highest organ of state power]. Forms of subordinate powers are: the executive [...] the judiciary".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This system was remodelled in the 1936 Soviet Constitution and introduced, with a few modifications, in all communist states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) For instance, present-day China, according to scholars Li Guoqiang and Zhao Junhua, practices "the unified exercise of state power by the people's congresses, the system of people's congresses makes a reasonable division of labour among the administrative, judicial, and procuratorial organs through the Constitution and laws".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Western scholars, such as Daniel Nelson, claim that the highest organ of state power are not as powerful as they seem to be, but acknowledge that they "have a place in the literature and rhetoric of the ruling parties which cannot be ignored—in the language of the party's intimacy with working masses, of its alleged knowledge about interests of working people, of social justice and socialist democracy, of the mass line and learning from the people."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) However, formally, these organs have the right to interfere in every state institution unless it itself has made a law that bars it from it. This also means there are no limits to politicisation, unlike in liberal democracies, where politicians are legally barred from interfering in judicial work. This is a firm rejection of the separation of powers since no institution can legally enforce limits on the highest organ of state power. Soviet legal theorists denounced judicial review and extra-parliamentary review as bourgeoisie institutions. They also perceived it as a limitation of the people's supreme power. The highest organ of state power and its organs oversaw the constitutional order.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Since the highest organ of state power is the supreme judge of constitutionality, its acts cannot be unconstitutional.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Marxist–Leninists view the constitution as a fundamental law and as an instrument of force.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The constitution is the source of law and legality.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Unlike in liberal democracies, the constitution of communist states is not a framework to limit the state's power. To the contrary, these constitutions seek to empower the state—believing the state to be an organ of class domination and law to be the expression of the interests of the dominant class. In this instance, it means that communist states conceive of constitutions as a tool to defend the class nature of their state against perceived enemies.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Unlike the relatively constant (and, in some instances, permanently fixed) nature of liberal constitutions, a communist state constitution is ever-changing.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Andrey Vyshinsky, a Procurator General of the Soviet Union during the 1930s, notes that the "Soviet constitutions represent the total of the historical path along which the Soviet state has travelled. At the same time, they are the legislative basis of subsequent development of state life."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) That is, the constitution sums up what has already been achieved and what the state aims to achieve in the future as well as a tool to analyse society.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This belief is also shared by the Chinese Communist Party, which argued that "the Chinese Constitution blazes a path for China, recording what has been won in China and what is yet to be conquered."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The preamble of the 1954 Chinese constitution outlines the historical tasks of the Chinese communists, "step by step, to bring about the socialist industrialisation of the country and, step by step, to accomplish the socialist transformation of agriculture, handicraft and capitalist industry and commerce."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Transmission belt

Vladimir Lenin conceived the transmission belt principle, which sought to create an information flow from the party to the people and from the people to the party in a communist state by creating interlinked institutions.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Originally conceived to institutionalised the relationship between the Party and the All-Russian Central Council of Trade Unions to safeguard the party from becoming divorced from the masses, or as Lenin put it, by turning the trade union into "the transmission belt from the Communist Party to the masses".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The flow was conceived to work both ways. The party would convey directives to the trade union that, in turn, would transmit them to its members, and the trade union would transmit the members' response to the directives back to the party.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The principle was later reconceptualised by Joseph Stalin in his book, Foundations of Leninism. He pointed to the fact that the working class had other organisations than the trade unions—everything from cooperative societies to non-party women fronts to elected representatives—and that "All these organisations, under certain conditions, are absolutely necessary for the working class."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The problem, according to Stalin, was that these organisations did not work uniformly. To solve this purported drawback, the Party leadership was necessary: "[the Party] is by reason of its experience and prestige the only organisation capable of centralising the leadership of the struggle of the proletariat, thus transforming each and every non-Party organisation of the working class into an auxiliary body and transmission belt linking the Party with the class."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The goal was that these mass organisations and institutions would "accept voluntarily" the Party's "political guidance".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Institutional variations

Civilian control of the military

Communist states have established two types of civil-military systems. The armed forces of most socialist states have historically been state institutions based on the Soviet model,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) but in China, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam, the armed forces are party-state institutions. However, several differences exist between the statist (Soviet) and the party-state models (China). In the Soviet model, the Soviet armed forces was led by the Council of Defense (an organ formed by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union). At the same time, the Council of Ministers was responsible for formulating defence policies.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The party leader was ex officio the Chairman of the Council of Defense.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Below the Council of Defense, there was the Main Military Council which was responsible for the strategic direction and leadership of the Soviet armed forces.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Council of Defence working organ was the General Staff tasked with analysing military and political situations as they developed.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The party controlled the armed forces through the Main Political Directorate (MPD) of the Ministry of Defense, a state organ that functioned "with the authority of a department of the CPSU Central Committee."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The MPD organised political indoctrination and created political control mechanisms at the centre to the company level in the field.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Formally, the MPD was responsible for organising party and Komsomol organs as well as subordinate organs within the armed forces; ensuring that the party and state retain control over the armed forces; evaluates the political performance of officers; supervising the ideological content of the military press; and supervising the political-military training institutes and their ideological content.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The head of the MPD was ranked fourth in military protocol, but it was not a member of the Council of Defense.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Administrative Organs Department of the CPSU Central Committee was responsible for implementing the party personnel policies and supervised the KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Defense.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

In the Chinese party-state model, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) is a party institution.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In the preamble of the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party, it is stated: "The Communist Party of China (CPC) shall uphold its absolute leadership over the People's Liberation Army and other people's armed forces."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The PLA carries out its work in accordance with the instructions of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Mao Zedong described the PLA's institutional situation as follows: "Every communist must grasp the truth, 'Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.' Our principle is that the party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the Party."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Central Military Commission (CMC) is both an organ of the state and the party—it is an organ of the CCP Central Committee and an organ of the national highest organ of state power, the National People's Congress.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The CCP General Secretary is ex officio party CMC Chairman and the President of the People's Republic of China is by right state CMC Chairman.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The composition of the party CMC and the state CMC are identical.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The CMC is responsible for the command of the PLA and determines national defence policies.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Fifteen departments report directly to the CMC and are responsible for everything from political work to administration of the PLA.[5] Of significance is that the CMC eclipses by far the prerogatives of the CPSU Administrative Organs Department while the Chinese counterpart to the Main Political Directorate supervises not only the military, but also intelligence, the security services, and counterespionage work.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Unlike in liberal democracies, active military personnel are members and partake in civilian institutions of governance.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This is the case in all communist states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has elected at least one active military figure to its CPV Politburo since 1986.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In the 1986–2006 period, active military figures sitting in the CPV Central Committee stood at an average of 9,2 per cent.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Military figures are also represented in the national highest organ of state power (the National Assembly) and other representative institutions.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In China, the two CMC vice chairmen have had by right office seats in the CCP Politburo since 1987.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Federal states

Most communist states that have existed have been unitary states. Still, there have been four exceptions to this rule: Czechoslovakia from 1968 until 1990, the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic until 1922, the Soviet Union and the Yugoslavia.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In all cases, these federal states were organised on ethnic lines, with a given ethnicity given their own titular republic.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The federal states of Russia, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia had a majority population of Russians in the case of Russia and the Soviet Union, and Czechs in Czechoslovakia. The largest ethnic group in Yugoslavia was the Serbs, but they did not constitute the majority.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Unlike the Soviet Union, which was a federal state created in place of the Russian Empire, which had expanded through colonisation and war, the federal states of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were, historically, a voluntary choice by a group of smaller states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Despite their communist state systems, these federations were not, according to scholar Anton Bebler, "particularly unique" if compared with federal non-communist states. Soviet communists were specifically against this conception from their state's inception in 1922, stating, "The Soviet federation is a federation of a new, superior type, differing in principle from a bourgeois federation."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The main argument put forward by the was that the Soviet Union was "voluntary union of socialist republics constructed on the base of the dictatorship of the [proletariat]", and were by extension significantly different from non-communist federal states.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The first federal communist state, the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, was proclaimed on 7 November 1917. Despite its name, the Russian Republic was not organised on federal lines and had a unitary state structure. The People's Commissariat of Nationalities was established to represent the interests of the non-Russian minorities. At the same time, the forerunner to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union refused to organise on federal lines since, according to The Communist Manifesto, "workingmen have no country", meaning that the communist party had to stand above national currents and unite every nationality on communist principles.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The leader of the Russian communists, Vladimir Lenin, had historically opposed federalism, "A centralised large State is a tremendous historical step forward on that way from medieval disjunction to a future socialist unity of the whole world."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) On 30 December 1922, the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was signed by the Russian Republic alongside the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. This treaty created an actual federal structure, but the rights of the republics were limited less than two years later when the 1924 Constitution of the Soviet Union was adopted.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) While the federal state was reorganised with the 1936 Soviet Constitution, between the 1936 Constitution and the 1977 Soviet Constitution, there were, according to scholar Henn-Jüri Uibopuu, "no new practice of the Soviet Union with regard to its Union Republics has come to our knowledge."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Each republic had their own supreme soviet, collective head of state, courts, and governments and had its own legislative powers granted to them by its own republican constitution as well as the All-Union one. However, the republican constitutions had few, if any, discernable differences from their All-Union counterparts except those devoted articles devoted to territorial administrative subdivisions. While republics had the right to adopt their own laws, the All-Union Constitution stated that laws emanating from All-Union institutions prevailed over republican laws in cases of divergence between them: "Ensurance of uniformity of legislative regulations throughout the territory of the USSR and establishment of the fundamentals of the legislation of the Union and the Union Republics."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) All-Union institutions were also given the right to to settle all matters that they perceived had an All-Union importance.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The main feature of Soviet federalism was centralisation. The 1977 Soviet Constitution states that the Soviet Union was an "indivisible federation", and the rights of the All-Union state were emphasised at the expense of republican rights. This was strengthened by the principle of democratic centralism, which emphasised centralising authority to the highest organ of state power, and by the fact that the party was a unitary organisation. The communist party treated the republics as ordinary territorial organisations and gave them no special rights in their relationship to the central party bodies.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Because of these reasons, scholars Julian Towster and John N. Hazard considered the Soviet Union "not a true federation; rather it is a quasi-federation or a union."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

During Alexander Dubček's short sting as first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in the late 1960s, the Czechoslovak state adopted a federal state structure on 1 January 1969. With the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and the rise to power of Gustáv Husák in the communist party, many federal reforms were reversed. In 1971, the Federal Assembly of Czechoslovakia adopted constitutional amendments that strengthened the federal government at the expense of the republics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) According to Timothy M. Kuehnlein, Czechoslovak federalism "provided less autonomy and power to its republics than did Yugoslavian federalism, yet it certainly provided more autonomy in determining social, educational and cultural issues than the Soviet form of federalism".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The federal state was made responsible for foreign affairs, defence, currency, the protection of the constitutional order, federal legislation and administration. In contrast, the republics were made responsible for education, culture, justice, health, trade, construction, and forest and water resources. The republics and the federal government had shared control over industry and agriculture, but 1971 amendments to the federal constitution extensively limited these powers.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Similarly to the Soviet Union, the Czechoslovak federal state had the ability to override republican legislation.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The federal state granted Czechs and Slovaks equal representation in the Federal Assembly, but in the government and in the central party leadership proportional representation was the norm. This meant that Slovaks never acquired more than one-third of posts in the federal government.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The communist party, similar to its Soviet counterpart, also remained unitary. During Dubček's leadership, there had been calls to federalise the party by creating a separate party organisation for Czechia as well; the Husák leadership opposed these moves.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Socialist Yugoslavia was formally proclaimed on 29 November 1945, and its federal constitution was adopted on 31 January 1946. The federalist structure was more or less identical to its Soviet counterpart at first, and it emphasised federal powers at the expense of the republics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Due to the Soviet–Yugoslav split of 1948, Yugoslav leaders moved to decentralise the political system and tried to conceive of a socialist model different to its Soviet counterpart.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Beginning in the 1960s, the federal authorities initiated several moves to decentralise authority to the republics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) While never officially becoming a federal party, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY) began progressively giving its republican branches more autonomy.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The republican branches elected candidates at their party congresses to sit on the LCY Central Committee and its Presidency. In other words, the central party organisation gave away its power of personnel appointments to its republican branches and, as a result, most federal officials made their political careers in the republics. In some cases, republican officials refused to take on federal positions since it meant abandoning their power base in the republics.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The only institution that was not federalised was the Yugoslav People's Army, which remained unitary.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) With the death of its long-standing leader, Josip Broz Tito in 1980, LCY politics became even more decentralised and began taking a federal-like form.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Policy disagreements within the federal state and the LCY took on a republican character, with the Serbs most prominently wanting to recentralise the state and party authority while the Slovenes sought further decentralisation.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Analysis

Western authors and organisations criticised countries such as the Soviet Union and China based on the lack of the representative nature of multi-party liberal democracy,[6][7] in addition to several other areas where socialist society and Western societies differed. Socialist societies were commonly characterised by state ownership or social ownership of the means of production either through administration through communist party organisations, democratically elected councils and communes, and co-operative structures—in opposition to the liberal democratic capitalist free-market paradigm of management, ownership and control by corporations and private individuals.[8] Communist states have also been criticised for the influence and outreach of their respective ruling parties on society, in addition to lack of recognition for some Western legal rights and liberties such as the right to own property and the restriction of the right to free speech.[9] The early economic development policies of communist states have been criticised for focusing primarily on the development of heavy industry.[citation needed]

Soviet advocates and socialists responded to criticism by highlighting the ideological differences in the concept of freedom. McFarland and Ageyev noted that "Marxist–Leninist norms disparaged laissez-faire individualism (as when housing is determined by one's ability to pay), also [condemning] wide variations in personal wealth as the West has not. Instead, Soviet ideals emphasized equality—free education and medical care, little disparity in housing or salaries, and so forth."[10] When asked to comment on the claim that former citizens of communist states enjoy increased freedoms, Heinz Kessler, former East German Minister of National Defence, replied: "Millions of people in Eastern Europe are now free from employment, free from safe streets, free from health care, free from social security."[11]

In his analysis of states run under Marxist–Leninist ideology, economist Michael Ellman of the University of Amsterdam notes that such states compared favorably with Western states in some health indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy.[12] A 1986 study published in the American Journal of Public Health and a 1992 study published in International Journal of Health Services stated, respectively, that "between countries at similar levels of economic development, socialist countries showed more favorable PQL (physical quality of life) outcomes" and that socialism was "for the most part, more successful than capitalism in improving the health conditions of the world's populations."[13][14]

Philipp Ther posits that there was an increase in the standard of living throughout Eastern Bloc countries as the result of modernisation programs under communist governments.[15] Similarly, Amartya Sen's own analysis of international comparisons of life expectancy found that several Marxist–Leninist states made significant gains and commented "one thought that is bound to occur is that communism is good for poverty removal."[16] The dissolution of the Soviet Union was followed by a rapid increase in poverty,[17][18][19] crime,[20][21] corruption,[22][23] unemployment,[24] homelessness,[25][26] rates of disease,[27][28][29] infant mortality, domestic violence,[30] and income inequality,[31] along with decreases in calorie intake, life expectancy, adult literacy, and income.[32]

See also

- List of socialist states

- List of anarchist communities

- Capitalist state

- List of anti-capitalist and communist parties with national parliamentary representation

- List of communist parties

- Marxism–Leninism–Maoism

- Stalinism

References

Books

- Why Did the Socialist System Collapse in Central and Eastern European Countries?: The Case of Poland, the Former Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Palgrave Macmillan. 2016. ISBN 978-0-312-12879-1.

- Russian Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Transition. Palgrave Macmillan. 2003. ISBN 978-1-349-40826-9.

- Blasko, Dennis (2006). The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781135988777.

- "People's Democracy". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 17. Macmillan Inc.. 1978a.

- "People's Democratic Revolution". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 17. Macmillan Inc.. 1978b.

- The Rise and Fall of Communism. The Bodley Head. 2009. ISBN 9780224078795.

- Marxism and the Leninist Revolutionary Model. Springer Publishing. 2014. ISBN 978-1-137-40913-3.

- Dimitrov, Vessellin (2006). "Bulgaria: A Core Against the Odds". Governing after Communism: Institutions and Policymaking (2nd ed.). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 159–203. ISBN 9780742540095.

- Ellman, Michael (2014). Socialist Planning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107427327.

- Evans, Daniel (1993). Soviet Marxism–Leninism: The Decline of an Ideology. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780275947637.

- Feldbrugge, F. J. M. (1985). "Council of Ministers". Encyclopedia of Soviet Law (2nd ed.). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 202–204. ISBN 1349060860.

- "工会 Trade Union". Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi. Australian National University Press. 2020. ISBN 9781788734790.

- Furtak, Robert K. (1987). The Political Systems of the Socialist States. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312625276.

- Gardner, John; Schöpflin, George; White, Stephen (1982). Communist Political Systems (2nd ed.). Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-333-44108-7.

- Soviet Law and Soviet Society. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1954. ISBN 978-94-015-0324-2.

- "An Assessment of Socialist Constitutional Supervision Models and Prospects for a Constitutional Supervision Committee in China: The Constitution As Commander?". China's Socialist Rule of Law Reforms Under Xi Jinping. Routledge. 2016. ISBN 978-1-138-95573-8.

- Harding, Neil (1981). "What Does It Mean to Call a Regime Marxist?". in Szajkowski, Bogdan. Marxist Governments. 1. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 22–33. ISBN 978-0-333-25704-3.

- Hazard, John (1985). "Constitutional Law". Encyclopedia of Soviet Law (2nd ed.). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 162–163. ISBN 1349060860.

- "Marx's Social Republic: Radical Republicanism and the Political Institutions of Socialism". Radical Republicanism: Recovering the Tradition's Popular Heritage. Oxford University Press. 2020. ISBN 978-0-19-879672-5.

- "Chapter 3: China's System of People’s Congresses". China’s Political System. China Social Sciences Press. 2020. ISBN 978-981-15-8362-9.

- Li, Lin (2017). Building the Rule of Law in China. Elsevier. ISBN 9780128119303.

- Loeber, Dietrich Andre (1984). "On the Status of the CPSU within the Soviet Legal System". The Party Statutes of the Communist World. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 1–22. ISBN 9789024729753.

- Nation, R. Craig (1992). Black Earth, Red Star: A History of Soviet Security Policy, 1917-1991. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801480072.

- Nelson, Daniel (1982). "Communist Legislatures and Communist Politics". Communist Legislatures in Comparative Perspective. 1. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–13. ISBN 1349060860.

- Communism in India. University of California Press. 1959. ISBN 0520346904.

- People's Power: Cuba's Experience with Representative Government. Rowman & Littlefield. 2003. ISBN 0-7425-2564-3.

- Reyes, Romeo A. (1997). "The Role of the State in Laos' Economic Development". Laos' Dilemmas and Options: The Challenge of Economic Transition in the 1990s. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 48–61. ISBN 0-312--17310-5.

- Rosser, Barkley; Rosser, Marianne (2003). Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262182348.

- A Dictionary of Scientific Socialism. Progress Publishers. 1984.

- Russian Politics and Society. Taylor & Francis. 2002. ISBN 0-415-22752-6.

- "The Demise of the Socialist Federations: Developmental Effects and Institutional Flaws of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia". Federalism Doomed?: European Federalism between Integration and Separation. Berghahn Books. 2002. ISBN 1-57181-206-7.

- Civil Society in China: The Legal Framework from Ancient Times to the "New Reform Era". Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-976589-8.

- Constitutional Change in the Contemporary Socialist World. Oxford University Press. 2020. ISBN 978-0-19-885134-9.

- Staar, Richard (1988). Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe (4th ed.). Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817976934.

- Stanković, Slobodan (1981). Staar, Richard F.. ed. The End of the Tito Era: Yugoslavia's Dilemmas. Hoover International Studies. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 9780817973629.

- Steele, David Ramsay (September 1999). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. ISBN 978-0875484495.

- Triska, Jan, ed (1968). Constitution of the Communist-Party States. Hoover Institution Publications. ISBN 978-0817917012.

- Tung, W. L. (2012). The Political Institutions of Modern China (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789401034432.

- Democratic centralism: An historical commentary. Manchester University Press. 1981. ISBN 0-7190-0802-6.

- Wilczynski, J. (2008). The Economics of Socialism after World War Two: 1945–1990. Aldine Transaction. ISBN 9780202362281.

- Williams, Raymond (1983). Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society, revised edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-520469-8.

Journal entries

- Bebler, Anton (1993). "Yugoslavia's variety of communist federalism and her demise". Communist and Post-Communist Studies (University of California Press) 26 (1): 72–86. doi:10.1016/0967-067X(93)90020-R.

- Belikov, Igor (1991). "Soviet Scholars' Debate on Socialist Orientation in the Third World". Millennium: Journal of International Studies (Sage Publications) 20 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1177/0305829891020001030.

- Beyme, Klaus von (1975). "A Comparative View of Democratic Centralism". Government and Opposition (Sage Publications) 10 (3): 259–277. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1975.tb00640.x.

- Bui, T. (2016). "Constitutionalizing Single Party Leadership in Vietnam: Dilemmas of Reform". Asian Journal of Comparative Law (Cambridge University Press) 11 (2): 219–234. doi:10.1017/asjcl.2016.22.

- Chang, Yu-nan (August 1956). "The Chinese Communist State System Under the Constitution of 1954". The Journal of Politics (The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Southern Political Science Association) 18 (3): 520–546. doi:10.2307/2127261.

- Denitch, Bogdan (1977). "The Evolution of Yugoslav Federalism". Publius (Oxford University Press) 7 (4): 107–117. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a038463.

- Edgington, Sylvia Woodby (1981). "The State of Socialist Orientation: A Soviet Model for Political Development". The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review (Brill Publishers) 8 (2): 223–251. doi:10.1163/187633281X00155. ISSN 1876-3324.

- Frankel, Joseph (1955). "Federalism in Yugoslavia". American Political Science Review (American Political Science Association) 49 (2): 416–430. doi:10.2307/1951812.

- Guins, George (July 1950). "Law Does not Wither Away in the Soviet Union". The Russian Review (John Wiley & Sons on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review) 9 (3): 187–204. doi:10.2307/125763.

- Hazard, John (August 1975). "Soviet Model for Marxian Socialist Constitutions". Cornell Law Review (Cornell University) 60 (6): 109–118. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.no/&httpsredir=1&article=4046&context=clr.

- "Socialism and Federation". Michigan Law Review 80 (5/6). 1984. doi:10.2307/1288473.

- "The Evolution of the Soviet Political System". Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science 35 (3). 1984. doi:10.2307/1174113.

- Imam, Zafar (July–September 1986). "The Theory of the Soviet State Today". The Indian Journal of Political Science (Indian Political Science Association) 47 (3): 382–398.

- "The Rise and Fall of the 'All-People's State': Recent Changes in the Soviet Theory of the State". Soviet Studies 20 (1). 1968.

- Keith, Richard (March 1991). "Chinese Politics and the New Theory of 'Rule of Law'". The China Quarterly (Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies) 125 (125): 109–118. doi:10.1017/S0305741000030320.

- Kokoshin, Andrey (October 2016). "2015 Military Reform in the People's Republic of China". Belfer Center Paper (Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs). https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/Military%20Reform%20China%20-%20web2.pdf.

- Kramer, Mark N. (January 1985). "Civil-Military Relations in the Warsaw Pact: The East European Component". International Affairs (Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Institute of International Affairs) 61 (1): 45–66. doi:10.2307/2619779.

- Miller, Alice (January 2018). "The 19th Central Committee Politburo". China Leadership Monitor (Hoover Institute) (55). https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/clm55-am-final.pdf.

- Mulvenon, James (January 2018). "The Cult of Xi and the Rise of the CMC Chairman Responsibility System". China Leadership Monitor (Hoover Institute) (55). https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/clm55-jm-final.pdf.

- "Some Aspects of Soviet Constitutional Theory". The Modern Law Review 12 (1). 1949.

- "Lenin on the Socialist State". India Quarterly 27 (1). 1971. doi:10.1177/097492847102700102.

- "The Ideological Foundations of Soviet Third World Policy: A Study of the Brezhnev Era (1964–82)". Strategic Studies 8 (2). 1985.

- "Lenin and the Crisis of Communism: The View from Inside". Government and Opposition 26 (1). 1991. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1991.tb01126.x.

- Skilling, H. Gordon (1951). "People's Democracy, the Proletarian Dictatorship and the Czechoslovak Path to Socialism". The American Slavic and East European Review 10 (2): 100–116. doi:10.2307/2491546.

- Skilling, H. Gordon (1961). "People's Democracy and the Socialist Revolution: A Case Study in Communist Scholarship. Part I". Soviet Studies (Taylor & Francis) 12 (3): pp. 241–262.

- Snyder, Stanley (1987). Soviet Troop Control and the Power Distribution (Thesis). Naval Postgraduate School. hdl:10945/22490.

- "Theory of the Polish People's Democracy". The Western Political Quarterly 9 (4). 1956. doi:10.2307/444501.

- Steiner, H. Arthur (1951). "The Role of the Chinese Communist Party". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 277: 56–66. doi:10.1177/000271625127700107. ISSN 0002-7162.

- Stone Sweet, Alec; Bu, Chong; Zhuo, Ding (25 May 2023). "Breaching the Taboo? Constitutional Dimensions of the New Chinese Civil Code". Asian Journal of Comparative Law: 1–26. doi:10.1017/asjcl.2023.18.

- Szente, Peter (1976). "Review Articles: The Hungarian Interpretation of Democratic Centralism". Government and Opposition 11 (2): 224–232. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1976.tb00658.x.

- "Khrushchëv's 'All-People's State'". Communist Affairs 2 (2). 1964.

- Tang, Peter S. H. (February 1980). "The Soviet, Chinese and Albanian Constitutions: Ideological Divergence and Institutionalized Confrontation?". Studies in Soviet Thought (Springer Publishing) 21 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1007/BF00832025.

- "Soviet Theory of Federalism". The Indian Journal of Political Science 36 (2). 1975.

- Thayer, Carlyle (2008). "Military Politics in Contemporary Vietnam". in Mietzner, Marcus. The Political Resurgence of the Military in Southeast Asia: Conflict and Leadership. Routledge. ISBN 9780415460354. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/133459/Thayer%20Military%20Politics%20in%20Vietnam.pdf.

- "Soviet Federalism under the New Soviet Constitution". Review of Socialist Law 5 (1). 1979. doi:10.1163/157303579X00127.

- Quigley, John (Autumn 1989). "Socialist Law and the Civil Law Tradition". The American Journal of Comparative Law (Oxford University Press) 37 (4): 781–808. doi:10.2307/840224. http://spg.snnu.edu.cn/kindeditor-4.1.10/attached/file/20170517/20170517102021182118.pdf. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

Reports

- Johnson, A. Ross (1983). "Political Leadership in Yugoslavia: Evolution of the League of Communists". Rand Publications Series: The Report (United States Department of State). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA412414.pdf. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

Thesis

- Kuehnlein, Timothy M. (1996). Political Stability and the Division of Czechoslovakia (Thesis). Western Michigan University.

- Poelzer, Greg (1989). An analysis of Grenada as a socialist-oriented state (Thesis). Carleton University. doi:10.22215/etd/1989-01666.

Web articles

- "China's Constitutional Rights: A Grand Illusion". Cato Institute. 1 September 2021. https://www.cato.org/blog/chinas-constitutional-rights-grand-illusion.

- Wang Weiguang (25 September 2014). "坚持人民民主专政,并不输理" (in Chinese). People's Daily. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2014/0925/c1001-25733854.html.

Footnotes

- ↑ Ball, Terence; Dagger, Richard, eds (2019). "Communism". Encyclopædia Britannica (revised ed.). https://www.britannica.com/topic/communism. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ↑ Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1935). Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation?. London: Longmans.

- ↑ Sloan, Pat (1937). Soviet Democracy. London: Left Book Club; Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- ↑ Farber, Samuel (1992). "Before Stalinism: The Rise and Fall of Soviet Democracy". Studies in Soviet Thought 44 (3): 229–230.

- ↑ Garafola, Cristina L. (23 September 2016). "People's Liberation Army Reforms and Their Ramifications". RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/blog/2016/09/pla-reforms-and-their-ramifications.html.

- ↑ Samuel P., Huntington (1970). Authoritarian Politics in Modern Society: The Dynamics of Established One-party Systems. Basic Books (AZ).

- ↑ Lowy, Michael (1986). "Mass Organization, Party and State: Democracy in its Transition to Socialism". Transition and Development: Problems of Third World Socialism (94): 264.

- ↑ Amandae, Sonja (2003). Rationalizing Capitalist Democracy: The Cold War Origins of Rational Choice Liberalism. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ "Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 25 January 2006. https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=17403&lang=en.

- ↑ McFarland, Sam; Ageyev, Vladimir; Abalakina-Paap, Marina (1992). "Authoritarianism in the Former Soviet Union". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63 (6): 1004–1010. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.1004.

- ↑ Parenti, Michael (1997). Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism. San Francisco: City Lights Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-87286-330-9.

- ↑ Ellman, Michael (2014). Socialist Planning. Cambridge University Press . p. 372. ISBN:1107427320.

- ↑ Cereseto, S.; Waitzkin, H. (1986). "Economic development, political-economic system, and the physical quality of life.". American Journal of Public Health 76 (6): 661–666. doi:10.2105/ajph.76.6.661. PMID 3706593.

- ↑ Navarro, V. (1992). "Has socialism failed? An analysis of health indicators under socialism". International Journal of Health Services 23 (2): 583–601. doi:10.2190/B2TP-3R5M-Q7UP-DUA2. PMID 1399170.

- ↑ Ther, Philipp (2016). Europe Since 1989: A History. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780691167374. https://press.princeton.edu/titles/10812.html. "As a result of communist modernization, living standards in Eastern Europe rose."

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard G. (November 1996). Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN:0415092353.

- ↑ McAaley, Alastair. Russia and the Baltics: Poverty and Poverty Research in a Changing World. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache%3A8M3JFdbXA7sJ%3Awww.crop.org%2Fviewfile.aspx%3Fid%3D381+&cd=10&ct=clnk&gl=nz. Retrieved 18 July 2016.