Arnold tongue

In mathematics, particularly in dynamical systems, Arnold tongues (named after Vladimir Arnold)[1][2] are a pictorial phenomenon that occur when visualizing how the rotation number of a dynamical system, or other related invariant property thereof, changes according to two or more of its parameters. The regions of constant rotation number have been observed, for some dynamical systems, to form geometric shapes that resemble tongues, in which case they are called Arnold tongues.[3]

Arnold tongues are observed in a large variety of natural phenomena that involve oscillating quantities, such as concentration of enzymes and substrates in biological processes[4] and cardiac electric waves. Sometimes the frequency of oscillation depends on, or is constrained (i.e., phase-locked or mode-locked, in some contexts) based on some quantity, and it is often of interest to study this relation. For instance, the outset of a tumor triggers in the area a series of substance (mainly proteins) oscillations that interact with each other; simulations show that these interactions cause Arnold tongues to appear, that is, the frequency of some oscillations constrain the others, and this can be used to control tumor growth.[3]

Other examples where Arnold tongues can be found include the inharmonicity of musical instruments, orbital resonance and tidal locking of orbiting moons, mode-locking in fiber optics and phase-locked loops and other electronic oscillators, as well as in cardiac rhythms, heart arrhythmias and cell cycle.[5]

One of the simplest physical models that exhibits mode-locking consists of two rotating disks connected by a weak spring. One disk is allowed to spin freely, and the other is driven by a motor. Mode locking occurs when the freely-spinning disk turns at a frequency that is a rational multiple of that of the driven rotator.

The simplest mathematical model that exhibits mode-locking is the circle map, which attempts to capture the motion of the spinning disks at discrete time intervals.

Standard circle map

Arnold tongues appear most frequently when studying the interaction between oscillators, particularly in the case where one oscillator drives another. That is, one oscillator depends on the other but not the other way around, so they do not mutually influence each other as happens in Kuramoto models, for example. This is a particular case of driven oscillators, with a driving force that has a periodic behaviour. As a practical example, heart cells (the external oscillator) produce periodic electric signals to stimulate heart contractions (the driven oscillator); here, it could be useful to determine the relation between the frequency of the oscillators, possibly to design better artificial pacemakers. The family of circle maps serves as a useful mathematical model for this biological phenomenon, as well as many others.[6]

The family of circle maps are functions (or endomorphisms) of the circle to itself. It is mathematically simpler to consider a point in the circle as being a point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in the real line that should be interpreted modulo [math]\displaystyle{ 2 \pi }[/math], representing the angle at which the point is located in the circle. When the modulo is taken with a value other than [math]\displaystyle{ 2 \pi }[/math], the result still represents an angle, but must be normalized so that the whole range [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 2 \pi] }[/math] can be represented. With this in mind, the family of circle maps is given by:[7]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_{i+1} = g(\theta_i) + \Omega }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] is the oscillator's "natural" frequency and [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is a periodic function that yields the influence caused by the external oscillator. Note that if [math]\displaystyle{ g(\theta) = \theta }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] the particle simply walks around the circle at [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] units at a time; in particular, if [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] is irrational the map reduces to an irrational rotation.

The particular circle map originally studied by Arnold,[8] and which continues to prove useful even nowadays, is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_{i+1} = \theta_i + \Omega + \frac{K}{2 \pi} \sin(2 \pi \theta_i) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is called coupling strength, and [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i }[/math] should be interpreted modulo [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math]. This map displays very diverse behavior depending on the parameters [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math]; if we fix [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = 1/3 }[/math] and vary [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math], the bifurcation diagram around this paragraph is obtained, where we can observe periodic orbits, period-doubling bifurcations as well as possible chaotic behavior.

Deriving the circle map

Another way to view the circle map is as follows. Consider a function [math]\displaystyle{ y(t) }[/math] that decreases linearly with slope [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math]. Once it reaches zero, its value is reset to a certain oscillating value, described by a function [math]\displaystyle{ z(t) = c + b \sin(2 \pi t) }[/math]. We are now interested in the sequence of times [math]\displaystyle{ \{ t_n \} }[/math] at which y(t) reaches zero.

This model tells us that at time [math]\displaystyle{ t_{n-1} }[/math] it is valid that [math]\displaystyle{ y(t_{n-1}) = c + b \sin(2 \pi t_{n-1}) }[/math]. From this point, [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] will then decrease linearly until [math]\displaystyle{ t_n }[/math], where the function [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] is zero, thus yielding:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} 0 &= y(t_{n-1}) - a \cdot (t_{n} - t_{n-1}) \\[0.5em] 0 &= \left[ c + b \sin(2 \pi t_{n-1}) \right] - a t_n + a t_{n-1} \\[0.5em] t_n &= \frac{1}{a} \left[ c + b \sin(2 \pi t_{n-1}) \right] + t_{n-1} \\[0.5em] t_n &= t_{n-1} + \frac{c}{a} + \frac{b}{a} \sin(2 \pi t_{n-1}) \end{align} }[/math]

and by choosing [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = c/a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ K = 2 \pi b/a }[/math] we obtain the circle map discussed previously:

- [math]\displaystyle{ t_n = t_{n-1} + \Omega + \frac{K}{2\pi} \sin(2 \pi t_{n-1}). }[/math]

Glass, L. (2001) argues that this simple model is applicable to some biological systems, such as regulation of substance concentration in cells or blood, with [math]\displaystyle{ y(t) }[/math] above representing the concentration of a certain substance.

In this model, a phase-locking of [math]\displaystyle{ N:M }[/math] would mean that [math]\displaystyle{ y(t) }[/math] is reset exactly [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] times every [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] periods of the sinusoidal [math]\displaystyle{ z(t) }[/math]. The rotation number, in turn, would be the quotient [math]\displaystyle{ N/M }[/math].[7]

Properties

Consider the general family of circle endomorphisms:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_{i+1} = g(\theta_i) + \Omega }[/math]

where, for the standard circle map, we have that [math]\displaystyle{ g(\theta) = \theta + (K / 2 \pi) \sin(2 \pi \theta) }[/math]. Sometimes it will also be convenient to represent the circle map in terms of a mapping [math]\displaystyle{ f(\theta) }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_{i+1} = f(\theta_i) = \theta_i + \Omega + \frac{K}{2 \pi} \sin(2 \pi \theta_i). }[/math]

We now proceed to listing some interesting properties of these circle endomorphisms.

P1. [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is monotonically increasing for [math]\displaystyle{ K \lt 1 }[/math], so for these values of [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] the iterates [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i }[/math] only move forward in the circle, never backwards. To see this, note that the derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f'(\theta) = 1 + K \cos(2 \pi \theta) }[/math]

which is positive as long as [math]\displaystyle{ K \lt 1 }[/math].

P2. When expanding the recurrence relation, one obtains a formula for [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_n }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_n = \theta_0 + n \Omega + \frac{K}{2 \pi} \sum_{i = 0}^{n-1} \sin(2 \pi \theta_i). }[/math]

P3. Suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_n = \theta_0 \bmod 1 }[/math], so they are periodic fixed points of period [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. Since the sine oscillates at frequency 1 Hz, the number of oscillations of the sine per cycle of [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i }[/math] will be [math]\displaystyle{ M = (\theta_n - \theta_0) \cdot 1 }[/math], thus characterizing a phase-locking of [math]\displaystyle{ n : M }[/math].[7]

P4. For any [math]\displaystyle{ p \in \mathbb{N} }[/math], it is true that [math]\displaystyle{ f(\theta + p) = f(\theta) + p }[/math], which in turn means that [math]\displaystyle{ f(\theta + p) = f(\theta) \bmod{1} }[/math]. Because of this, for many purposes it does not matter if the iterates [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i }[/math] are taken modulus [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] or not.

P5 (translational symmetry).[9][7] Suppose that for a given [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] there is a [math]\displaystyle{ n : M }[/math] phase-locking in the system. Then, for [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega' = \Omega + p }[/math] with integer [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], there would be a [math]\displaystyle{ n : (M + np) }[/math] phase-locking. This also means that if [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_0, \dots, \theta_n }[/math] is a periodic orbit for parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math], then it is also a periodic orbit for any [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega' = \Omega + p, p \in \mathbb{N} }[/math].

P6. For [math]\displaystyle{ K = 0 }[/math] there will be phase-locking whenever [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] is a rational. Moreover, let [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = p/q \in \mathbb{Q} }[/math], then the phase-locking is [math]\displaystyle{ q : p }[/math].

Mode locking

For small to intermediate values of K (that is, in the range of K = 0 to about K = 1), and certain values of Ω, the map exhibits a phenomenon called mode locking or phase locking. In a phase-locked region, the values θn advance essentially as a rational multiple of n, although they may do so chaotically on the small scale.

The limiting behavior in the mode-locked regions is given by the rotation number.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \omega=\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{\theta_n}{n}. }[/math][10]

which is also sometimes referred to as the map winding number.

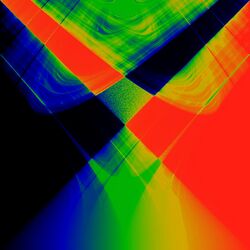

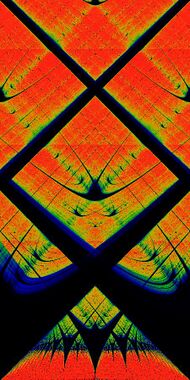

The phase-locked regions, or Arnold tongues, are illustrated in yellow in the figure to the right. Each such V-shaped region touches down to a rational value Ω = p/q in the limit of K → 0. The values of (K,Ω) in one of these regions will all result in a motion such that the rotation number ω = p/q. For example, all values of (K,Ω) in the large V-shaped region in the bottom-center of the figure correspond to a rotation number of ω = 1/2. One reason the term "locking" is used is that the individual values θn can be perturbed by rather large random disturbances (up to the width of the tongue, for a given value of K), without disturbing the limiting rotation number. That is, the sequence stays "locked on" to the signal, despite the addition of significant noise to the series θn. This ability to "lock on" in the presence of noise is central to the utility of the phase-locked loop electronic circuit.[citation needed]

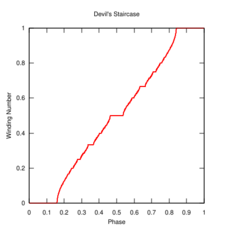

There is a mode-locked region for every rational number p/q. It is sometimes said that the circle map maps the rationals, a set of measure zero at K = 0, to a set of non-zero measure for K ≠ 0. The largest tongues, ordered by size, occur at the Farey fractions. Fixing K and taking a cross-section through this image, so that ω is plotted as a function of Ω, gives the "Devil's staircase", a shape that is generically similar to the Cantor function. One can show that for K<1, the circle map is a diffeomorphism, there exist only one stable solution. However, as K>1 this holds no longer, and one can find regions of two overlapping locking regions. For the circle map it can be shown that in this region, no more than two stable mode locking regions can overlap, but if there is any limit to the number of overlapping Arnold tongues for general synchronised systems is not known.[citation needed]

The circle map also exhibits subharmonic routes to chaos, that is, period doubling of the form 3, 6, 12, 24,....

Chirikov standard map

The Chirikov standard map is related to the circle map, having similar recurrence relations, which may be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \theta_{n+1} &= \theta_n + p_n + {\frac K {2\pi}} \sin(2\pi\theta_n)\\ p_{n+1} &= \theta_{n+1} - \theta_n \end{align} }[/math]

with both iterates taken modulo 1. In essence, the standard map introduces a momentum pn which is allowed to dynamically vary, rather than being forced fixed, as it is in the circle map. The standard map is studied in physics by means of the kicked rotor Hamiltonian.

Applications

Arnold tongues have been applied to the study of

- Cardiac rhythms - see (Glass, L. Guevara, M.R.) and (McGuinness, M. Hong, Y.)

- Synchronisation of a resonant tunneling diode oscillators[11]

Gallery

See also

Notes

- ↑ Arnol'd, V.I. (1961). "Small denominators. I. Mapping the circle onto itself". Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk. Seriya Matematicheskaya 25 (1): 21–86. http://mi.mathnet.ru/eng/izv3366. Section 12 in page 78 has a figure showing Arnold tongues.

- ↑ Translation to english of Arnold's paper: S. Adjan; V. I. Arnol'd; S. P. Demuškin; Ju. S. Gurevič; S. S. Kemhadze; N. I. Klimov; Ju. V. Linnik; A. V. Malyšev et al.. Eleven Papers on Number Theory, Algebra and Functions of a Complex Variable. 46. American Mathematical Society Translations Series 2. https://bookstore.ams.org/trans2-46/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Jensen, M.H.; Krishna, S. (2012). "Inducing phase-locking and chaos in cellular oscillators by modulating the driving stimuli". FEBS Letters 586 (11): 1664–1668. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.044. PMID 22673576.

- ↑ Gérard, C.; Goldbeter, A. (2012). "The cell cycle is a limit cycle". Mathematical Modelling of Natural Phenomena 7 (6): 126–166. doi:10.1051/mmnp/20127607.

- ↑ Nakao, M.; Enkhkhudulmur, T.E.; Katayama, N.; Karashima, A. (2014). "Entrainability of cell cycle oscillator models with exponential growth of cell mass". Conference of Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE. pp. 6826–6829.

- ↑ Glass, L. (2001). "Synchronization and rhythmic processes in physiology". Nature 410 (6825): 277–284. doi:10.1038/35065745. PMID 11258383. Bibcode: 2001Natur.410..277G.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Glass, L.; Perez, R. (1982). "Fine structure of phase locking". Physical Review Letters 48 (26): 1772. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.1772. Bibcode: 1982PhRvL..48.1772G.

- ↑ He studied it using cosine instead of sine; see page 78 of Arnol'd, V.I. (1961).

- ↑ Guevara, M.R.; Glass, L. (1982). "Phase locking, period doubling bifurcations and chaos in a mathematical model of a periodically driven oscillator: A theory for the entrainment of biological oscillators and the generation of cardiac dysrhythmias". Journal of Mathematical Biology 14 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1007/BF02154750. PMID 7077182.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric. "Map Winding Number". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/MapWindingNumber.html.

- ↑ Romeira, B.; Figueiredo, J.M.; Ironside, C.N.; Slight, T. (2009). "Chaotic dynamics in resonant tunneling optoelectronic voltage controlled oscillators". IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 21 (24): 1819–1821. doi:10.1109/LPT.2009.2034129. Bibcode: 2009IPTL...21.1819R.

References

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Circle Map". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CircleMap.html.

- Boyland, P.L. (1986). "Bifurcations of circle maps: Arnol'd tongues, bistability and rotation intervals". Communications in Mathematical Physics 106 (3): 353–381. doi:10.1007/BF01207252. Bibcode: 1986CMaPh.106..353B. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104115779.

- Gilmore, R.; Lefranc, M. (2002). The Topology of Chaos: Alice in Stretch and Squeezeland. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-40816--6. - Provides a brief review of basic facts in section 2.12.

- Glass, L.; Guevara, M.R.; Shrier, A.; Perez, R. (1983). "Bifurcation and chaos in a periodically stimulated cardiac oscillator". Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 7 (1–3): 89–101. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(83)90119-7. Bibcode: 1983PhyD....7...89G. - Performs a detailed analysis of heart cardiac rhythms in the context of the circle map.

- McGuinness, M.; Hong, Y.; Galletly, D.; Larsen, P. (2004). "Arnold tongues in human cardiorespiratory systems". Chaos 14 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1063/1.1620990. PMID 15003038. Bibcode: 2004Chaos..14....1M.

External links

- Circle map with interactive Java applet

|