Interval exchange transformation

In mathematics, an interval exchange transformation[1] is a kind of dynamical system that generalises circle rotation. The phase space consists of the unit interval, and the transformation acts by cutting the interval into several subintervals, and then permuting these subintervals. They arise naturally in the study of polygonal billiards and in area-preserving flows.

Formal definition

Let and let be a permutation on . Consider a vector of positive real numbers (the widths of the subintervals), satisfying

Define a map called the interval exchange transformation associated with the pair as follows. For let

Then for , define

if lies in the subinterval . Thus acts on each subinterval of the form by a translation, and it rearranges these subintervals so that the subinterval at position is moved to position .

Properties

Any interval exchange transformation is a bijection of to itself that preserves the Lebesgue measure. It is continuous except at a finite number of points.

The inverse of the interval exchange transformation is again an interval exchange transformation. In fact, it is the transformation where for all .

If and (in cycle notation), and if we join up the ends of the interval to make a circle, then is just a circle rotation. The Weyl equidistribution theorem then asserts that if the length is irrational, then is uniquely ergodic. Roughly speaking, this means that the orbits of points of are uniformly evenly distributed. On the other hand, if is rational then each point of the interval is periodic, and the period is the denominator of (written in lowest terms).

If , and provided satisfies certain non-degeneracy conditions (namely there is no integer such that ), a deep theorem which was a conjecture of M.Keane and due independently to William A. Veech[2] and to Howard Masur[3] asserts that for almost all choices of in the unit simplex the interval exchange transformation is again uniquely ergodic. However, for there also exist choices of so that is ergodic but not uniquely ergodic. Even in these cases, the number of ergodic invariant measures of is finite, and is at most .

Interval maps have a topological entropy of zero.[4]

Odometers

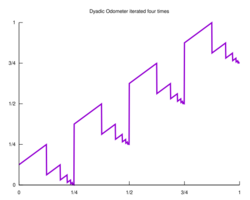

The dyadic odometer can be understood as an interval exchange transformation of a countable number of intervals. The dyadic odometer is most easily written as the transformation

defined on the Cantor space The standard mapping from Cantor space into the unit interval is given by

This mapping is a measure-preserving homomorphism from the Cantor set to the unit interval, in that it maps the standard Bernoulli measure on the Cantor set to the Lebesgue measure on the unit interval. A visualization of the odometer and its first three iterates appear on the right.

Higher dimensions

Two and higher-dimensional generalizations include polygon exchanges, polyhedral exchanges and piecewise isometries.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Keane, Michael (1975), "Interval exchange transformations", Mathematische Zeitschrift 141: 25–31, doi:10.1007/BF01236981.

- ↑ "Gauss measures for transformations on the space of interval exchange maps", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 115 (1): 201–242, 1982, doi:10.2307/1971391.

- ↑ Masur, Howard (1982), "Interval exchange transformations and measured foliations", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 115 (1): 169–200, doi:10.2307/1971341.

- ↑ Matthew Nicol and Karl Petersen, (2009) "Ergodic Theory: Basic Examples and Constructions", Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science, Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30440-3_177

- ↑ Piecewise isometries – an emerging area of dynamical systems, Arek Goetz

References

- Artur Avila and Giovanni Forni, Weak mixing for interval exchange transformations and translation flows, arXiv:math/0406326v1, https://arxiv.org/abs/math.DS/0406326

|