Astronomy:(486958) 2014 MU69

| |

| Discovery [1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Hubble Space Telescope |

| Discovery site | Earth's orbit |

| Discovery date | 26 June 2014 |

| Designations | |

| (486958) 2014 MU69 | |

| Ultima Thule (unofficial)[3] 2014 MU69 · PT1 [4] 1110113Y [5] · 11 [6] | |

| Minor planet category | TNO [1] · cubewano [5][7] distant [2] |

| Orbital characteristics [1] | |

| Epoch 4 September 2017 (JD 2458000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 5[1] · 2[2] | |

| Observation arc | 118 days[1] · 851 days[2] |

| |{{{apsis}}}|helion}} | 46.552 AU |

| |{{{apsis}}}|helion}} | 42.364 AU |

| 44.458 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0471 · 0.036[8] |

| Orbital period | 296.44 yr (108,274 d) |

| Mean anomaly | 306.31° |

| Mean motion | 0° 0m 11.88s / day |

| Inclination | 2.4518° · 1.9° [8] |

| Longitude of ascending node | 158.99° |

| 183.66° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 20 km + 18 km[9] (as contact/binary system) |

| Mean diameter | 25–45 km[6] 30 km[10] 30–45 km[5] |

| Geometric albedo | 0.04–0.10 (assumed)[5] 0.04–0.15 (assumed)[6] |

| Apparent magnitude | 26.8[11] |

| Absolute magnitude (H) | 11.1[1] |

(486958) 2014 MU69, previously designated PT1 and 1110113Y, and nicknamed Ultima Thule by the New Horizons team,[3] is a trans-Neptunian object from the Kuiper belt located in the outermost regions of the Solar System. It was discovered by astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope on 26 June 2014.[2] The irregular shaped classical Kuiper belt object is a suspected contact binary or close binary system and measures approximately 30 kilometers (19 miles) in diameter.

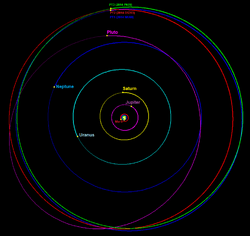

In August 2015, this object was selected as the next target for the New Horizons probe shortly after it had visited Pluto. The flyby will occur on 1 January 2019, which will make it the farthest object in the Solar System ever to be visited by a spacecraft.[4] After four course changes in October and November 2015, New Horizons is on course toward 2014 MU69.[12][13]

On 13 March 2018, NASA announced that (486958) 2014 MU69 would receive the nickname Ultima Thule. The decision was based on the results of a public voting campaign.[14] Ultima Thule /ˈθuːliː/, or Ultima for short, serves as an unofficial name for the object until the IAU decides on an official name at some point after the flyby.[3]

History

Discovery

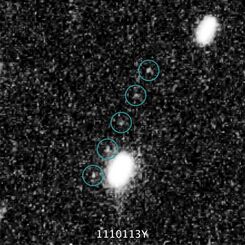

On 26 June 2014, 2014 MU69 was discovered using the Hubble Space Telescope during a preliminary survey to find a suitable Kuiper belt object for the New Horizons probe to fly by. The discovery required the use of the Hubble Space Telescope, because ground-based observations had not found a Kuiper belt object in the zone of space that can be accessed by New Horizons. With an apparent magnitude of nearly 27 2014 MU69 is too faint for all but the most powerful telescopes. The Hubble Space Telescope is also capable of very precise astrometry and hence a reliable orbit determination.[11][15][16]

Designation

When 2014 MU69 was first observed, it was labelled 1110113Y,[17] and nicknamed "11", for short.[6][4] Its existence as a potential target of the New Horizons probe was announced by NASA in October 2014[18][19] and it was unofficially designated as "Potential Target 1", or PT1. Its official designation, 2014 MU69, was assigned by the Minor Planet Center (MPC) in March 2015 after sufficient orbital information was gathered.[4] After further observations pinning down its orbit, it was officially given the permanent minor planet number (486958) on 12 March 2017 (M.P.C. 103886).[20]

Its provisional designation, 2014 MU69, indicates that it was the 1745th object discovered during the second half of June 2014. A proper name for the object will be selected in due course,[21] after the flyby when its nature is better known.[14] NASA invited suggestions from the public on a nickname to be used in the meantime.[14]

On 13 March 2018, NASA has announced that (486958) 2014 MU69 will be nicknamed Ultima Thule, after a distant place located beyond the "borders of the known world". The popular campaign wrapped up on December 6, 2017. The campaign involved 115,000 participants from around the world, who nominated some 34,000 names. Of those, 37 names reached the ballot for voting and were evaluated for popularity – this included eight names suggested by the New Horizons team and 29 nominated by the public. The team then narrowed its selection to the 29 publicly nominated names and gave preference to names near the top of the polls. Ultima Thule was nominated by about 40 members of the public and one of the highest vote-getters among all name nominees.[3]

Characteristics

In 2014, the object was first estimated to have a diameter of 30–45 km (20–30 mi) based on its brightness and distance.[5] Observations in 2017 concluded that 2014 MU69 is no more than 30 km (20 mi) long and very elongated. It may actually be a close or contact binary.[10] An occultation of a star on July 17, 2017 revealed a two-lobed shape, with diameters of 20 and 18 km (12 and 11 miles), respectively.[9] This means that 2014 MU69 is likely a primordial binary in the Kuiper Belt.[clarification needed][22]

Its orbital period around the Sun is slightly more than 295 years and it has a low inclination and low eccentricity compared to other objects in the Kuiper belt.[23] These orbital properties mean that it is a cold classical Kuiper belt object which is unlikely to have undergone significant perturbations.[5] Observations in May and July 2015 as well as in July and October 2016 greatly reduced the uncertainties in the orbit.[11][2] The updated orbit parameters are available in the MPC database.

2014 MU69 has a red spectrum, and is the smallest Kuiper belt object to have its colors measured.[24]

Between 25 June and 4 July 2017, the Hubble Space Telescope spent 24 orbits observing 2014 MU69, in an effort to both determine its rotation period and further reduce the orbit uncertainty.[25] First results show that the brightness of 2014 MU69 varies by less than 20 percent as it rotates.[9] This places significant constraints on the axis ratio of 2014 MU69 to <1.14 assuming an equatorial view. Together with the fact that its shape has been shown to be very irregular,[10] the small amplitude indicates that its pole is pointed towards Earth. This means that the timing of the New Horizons fly-by does not need to be adjusted to look at the "larger" axis of the object, simplifying the engineering of the fly-by significantly. The small amplitude makes it difficult to uniquely identify the rotation period at this time. Distant satellites of 2014 MU69 have been excluded to a depth of >29th magnitude.[26]

Stellar occultations

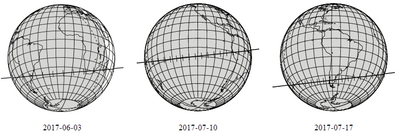

In June and July 2017, 2014 MU69 occulted three background stars.[27] The team behind New Horizons has formed a specialised "KBO Chasers" team to observe these stellar occultations from South America, Africa and the Pacific Ocean.[28][29][30]

On 3 June 2017, two teams of NASA scientists tried to detect the shadow of 2014 MU69 from Argentina and South Africa .[31] When they found that none of their telescopes had observed the object's shadow, it was initially speculated that 2014 MU69 might be neither as large nor as dark as previously expected, and that it might be highly reflective or even a swarm.[32][33] Additional data taken with the Hubble Space Telescope in June and July 2017 revealed that the telescopes had been placed in the wrong location, and that these speculations were wrong.[34][35]

On 10 July 2017, the airborne telescope SOFIA was successfully placed close to the predicted centerline for the second occultation while flying over the Pacific Ocean from Christchurch, New Zealand. The main purpose of those observations was the search for hazardous material like rings or dust near 2014 MU69 that could threaten the New Horizons spacecraft during its flyby in 2019. Data collection has been successful. A preliminary analysis suggested that the central shadow was missed;[36] only in January 2018 it was realized that SOFIA had indeed observed a very brief dip from the central shadow.[37] The data collected by SOFIA will also be valuable to put constraints on dust near 2014 MU69.[38][39] Detailed results of the search for hazardous material were presented on the 49th Meeting of the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences, on 20 October 2017.[40]

On 17 July 2017, the Hubble Space Telescope was used to check for debris around 2014 MU69, setting constraints on rings and debris within the Hill sphere of 2014 MU69 at distances of up to 75,000 km from the main body.[41] For the third and final occultation, team members set up another ground-based "fence line" of 24 small, mobile telescopes along the predicted ground track of the occultation shadow in southern Argentina (Chubut and Santa Cruz Provinces) to try to better constrain, or even determine, the size of 2014 MU69.[29][42] The average spacing between these telescopes was as small as 4.5 km (2.8 mi).[43] Using the latest observations from Hubble, the position of 2014 MU69 was known with much better precision than for the June 3 occultation, and this time the shadow of 2014 MU69 was successfully observed by at least five of the mobile telescopes.[42] Combined with the SOFIA observations, this will put good constraints on possible debris near 2014 MU69.[39][35]

Results from the occultation on 17 July show that 2014 MU69 has a very irregular shape (an "extreme prolate spheroid"), or may even be a close or contact binary.[10][44] According to the number and duration of the observed chords, 2014 MU69 has two "lobes", with diameters of 20 km and 18 km, respectively.[9] A preliminary analysis of all collected data did suggest that 2014 MU69 may be accompanied by an orbiting moonlet, which is about 200-300km away.[45][46] However, it was later realized that a problem with the data processing software was responsible for a shift in the apparent location of the target. After accounting for the software bug, the short dip observed on 10 July is now considered to be a detection of the primary body.[37]

There have been two potentially useful 2014 MU69 occultations predicted for 2018: One on 16 July, one on 4 August. Neither of these was as good as the three 2017 events.[27]

No attempts were made to observe the 16 July 2018 occultation, which took place over the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean. For the 4 August 2018 event, two teams, consisting of about 50 researchers in total, went to locations in Senegal and Colombia.[47]

The event gathered media attention in Senegal, where it was used as an opportunity for science outreach.[48] Despite some stations being affected by bad weather, the event was successfully observed, as reported by the New Horizons team.[49] Initially, it was unclear whether a chord on the target had been recorded. On 6 September 2018, NASA confirmed that the star has indeed been seen to dip by at least one observer, providing important information about the size and shape of 2014 MU69.[50]

Hubble observations were carried out on 4 August 2018, to support the occultation campaign.[51][47] Hubble could not be placed in the narrow path of the occultation, but due to the favourable location of Hubble at the time of the event, the space telescope was able to probe the region down to 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) from 2014 MU69. This is much closer than the 20,000 kilometres (12,000 mi) region that could be observed during the 17 July 2017 occultation. No brightness changes of the target star have been seen by Hubble, ruling out any optically thick rings or debris down to 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) from Ultima Thule.[50]

Detailed results of the 2017 and 2018 occultation campaigns will be presented at the 50th meeting of the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences, on 26 October 2018.[52]

Exploration

Having completed its flyby of Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft has been maneuvered for a flyby of 2014 MU69. Closest approach will occur at 12:33 am, January 1, 2019 (EST),[46] at which point it will be 43.4 astronomical unit|AU from the Sun in the constellation Sagittarius.[53][54][55][56] At this distance, the one-way transit time for radio signals between Earth and New Horizons will be 6 hours.[46] The first image from New Horizons was taken on August 16, 2018, more than four months before the flyby.[57] If obstacles are detected, the spacecraft has the option of diverting to a more distant rendezvous until mid-December 2018.[46]

2014 MU69 is the first object to be targeted for a flyby that was discovered after the visiting spacecraft was launched.[11] New Horizons is planned to come within 3,500 km (2,200 mi) of 2014 MU69, three times closer than the spacecraft's earlier encounter with Pluto. Images with a resolution as fine as 30 m (98 ft) to 70 m (230 ft) are expected.[46][58]

The science objectives of the flyby include characterizing the geology and morphology of 2014 MU69, mapping the surface composition (searching for ammonia, carbon monoxide, methane, and water ice). Searches will be conducted of the surrounding environment to detect possible orbiting moonlets, a coma, or rings.[46]

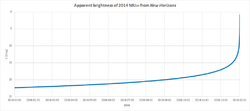

New Horizons made its first detection of 2014 MU69 on 16 August 2018, from a distance of 107 million mi (172 million km). At that time, 2014 MU69 was visible at magnitude 20, in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius.[59] 2014 MU69 is expected to be magnitude 18 by mid-November, and magnitude 15 by mid-December. It will reach naked eye brightness (magnitude 6) just 3-4 hours before closest approach.[60]

Gallery

Size of 2014 MU69 comparison: Massachusetts coast and Rosetta's target, comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

New Horizons trajectory and the orbits of Pluto and 2014 MU69.

2014 MU69 briefly blocked the light from an unnamed star (center) during an occultation on 17 July 2017.

2014 MU69 as a binary object

(artist's concept; 4 August 2017).[36]2014 MU69 as a single object

(artist's concept; 4 August 2017).[36]

See also

- List of minor planets targeted for spacecraft visitation

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 486958 (2014 MU69)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2486958. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "486958 (2014 MU69)". Minor Planet Center. http://www.minorplanetcenter.net/db_search/show_object?object_id=486958. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "New Horizons Chooses Nickname for ‘Ultimate’ Flyby Target". NASA. 13 March 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/new-horizons-chooses-nickname-for-ultimate-flyby-target. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Talbert, Tricia (28 August 2015). "NASA's New Horizons Team Selects Potential Kuiper Belt Flyby Target". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-new-horizons-team-selects-potential-kuiper-belt-flyby-target. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Lakdawalla, Emily (15 October 2014). "Finally! New Horizons has a second target". Planetary Society blog. Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141015230432/http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2014/10151024-finally-new-horizons-has-a-kbo.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Buie, Marc (15 October 2014). "New Horizons HST KBO Search Results: Status Report". Space Telescope Science Institute. p. 23. http://www.stsci.edu/institute/stuc/oct-2014/New-Horizons.pdf.

- ↑ Marc W. Buie. "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 486958". SwRI (Space Science Department). http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~buie/kbo/astrom/486958.html. Retrieved 2018-02-18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stern, Alan (August 2015). "OPAG: We Did It!". Presentation to the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) of the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Universities Space Research Association. p. 33. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/opag/meetings/aug2015/presentations/day-2/13_stern.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Alan Stern (8 August 2017). "The PI's Perspective: The Heroes of the DSN and the 'Summer of MU69'". New Horizons – NASA. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/PI-Perspectives.php?page=piPerspective_08_08_2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "New Horizons' Next Target Just Got a Lot More Interesting". 3 August 2017. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/new-horizons-next-target-just-got-a-lot-more-interesting.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Lakdawalla, Emily (1 September 2015). "New Horizons extended mission target selected". Planetary Society blog. Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/09011608-new-horizons-extended-mission-pt1.html.

- ↑ Dunn, Marcia (22 October 2015). "NASA's New Horizons on new post-Pluto mission". AP News. http://apnews.excite.com/article/20151022/us-sci--pluto-next_stop-3b1bf3f8fc.html. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ "NASA's New Horizons Completes Record-Setting Kuiper Belt Targeting Maneuvers". New Horizons Team. 5 November 2015. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20151105. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Help Nickname New Horizons’ Next Flyby Target". NASA. November 6, 2017. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/help-nickname-new-horizons-next-flyby-target. "NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt is looking for your ideas on what to informally name its next flyby destination, a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) past Pluto."

- ↑ J. R. Spencer et al. (2015). "The Successful Search for a Post-Pluto KBO Flyby Target for New Horizons Using the Hubble Space Telescope". European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC) Abstract (Copernicus Office). http://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC2015/EPSC2015-417.pdf.

- ↑ S. B. Porter (2017). "Ultra-High Resolution Orbit Determination of (486958) 2014 MU69: Predicting an Occultation with 1% of an Orbit". 504.02. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ↑ "Hubble Survey Finds Two Kuiper Belt Objects to Support New Horizons Mission". HubbleSite news release. Space Telescope Science Institute. 1 July 2014. http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2014/35/image/a/.

- ↑ "NASA's Hubble Telescope Finds Potential Kuiper Belt Targets for New Horizons Pluto Mission". HubbleSite. 15 October 2014. http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2014/47/.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (15 October 2014). "Hubble Telescope Spots Post-Pluto Targets for New Horizons Probe". Space.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141015233156/http://www.space.com/27445-hubble-telescope-new-horizons-kuiper-belt.html.

- ↑ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. http://www.minorplanetcenter.net/iau/ECS/MPCArchive/MPCArchive_TBL.html. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ↑ Stern, Alan (28 April 2017). "No Sleeping Back on Earth!". https://blogs.nasa.gov/pluto/2017/04/28/no-sleeping-back-on-earth/. Retrieved 2017-09-18. "we’re going to give 2014 MU69 a real name, rather than just the “license plate” designator it has now. The details of how we’ll name it are still being worked out"

- ↑ A. H. Parker (2017). "Multiplicity of the New Horizons Extended Mission Target (486958) 2014 MU69". 504.04. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ Porter, S. B.; Parker, A. H., eds. "Orbits and Accessibility of Potential New Horizons KBO Encounter Targets" (PDF). 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015). http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2015/pdf/1301.pdf.

- ↑ "Scientists Determine Color of Kuiper Belt Objects JR1 and MU69 | Planetary Science, Space Exploration" (in en-US). Sci-News.com. http://www.sci-news.com/space/color-kuiper-belt-objects-04290.html. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Lightcurve of New Horizons Encounter TNO 2014 MU69". http://archive.stsci.edu/proposal_search.php?mission=hst&id=14627. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ S. D. Benecchi (2017). "The HST Lightcurve of (486958) 2014MU69". 504.07. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Mission Support of the New Horizons 2014 MU69 Encounter via Stellar Occultations". http://www.boulder.swri.edu/MU69_occ/case.html. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "2014MU69 occultation campaign". http://www.boulder.swri.edu/MU69_occ/. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "KBO Chasers". http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Mission/KBO-Chasers.php. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ M. W. Buie (2017). "Overview of the strategies and results of the 2017 occultation campaigns involving (486958) 2014 MU69". 504.01. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ A. J. Verbiscer (2017). "Portable Telescopic Observations of the 3 June 2017 Stellar Occultation by New Horizons Kuiper Extended Mission Target (486958) 2014 MU69". 504.05. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ "New Mysteries Surround New Horizons’ Next Flyby Target: NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft doesn’t zoom past its next science target until New Year’s Day 2019, but the Kuiper Belt object, known as 2014 MU69, is already revealing surprises.". 5 July 2017. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/new-mysteries-surround-new-horizons-next-flyby-target.

- ↑ "The Case of the Dog that Didn’t Bark in the Night". 7 July 2017. https://cdan4th.wordpress.com/2017/07/07/mu69occ_4/.

- ↑ "June 3rd got the hazard search we wanted done but didn't put telescopes in the right place because back then we didn't have the MU69 orbit prediction well enough in hand. Subsequent HST June–July data helped with that.". 20 July 2017. http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?showtopic=5368&st=412&start=405.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "The #mu69occ campaign: Occam's razor wins again...". 21 July 2017. http://cosmos4u.blogspot.de/2017/07/the-mu69occ-campaign-occams-razor-wins.html.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Chang, Kenneth (8 August 2017). "Chasing Shadows for a Glimpse of a Tiny World Beyond Pluto". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/science/new-horizons-nasa-pluto-mu69-occultations.html. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "New Horizons prepares for encounter with 2014 MU69". 24 January 2018. http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2018/0124-new-horizons-prepares-for-2014mu69.html.

- ↑ "SOFIA to Make Advance Observations of Next New Horizons Flyby Object". 10 July 2017. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20170710.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "SOFIA in Right Place at Right Time to Study Next New Horizons Flyby Object". 11 July 2017. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20170711.

- ↑ E. F. Young (2017). "Debris search around (486958) 2014 MU69: Results from SOFIA and ground-based occultation campaigns". 504.06. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ J. Kammer (2017). "Probing the Hill Sphere of 2014 MU69 with HST FGS". 216.04. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "NASA's New Horizons Team Strikes Gold in Argentina". 19 July 2017. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20170719.

- ↑ "2014 MU69 presentation". https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3i7oVvbtAXgSEJNRFNkTU82Q00/view.

- ↑ A. M. Zangari (2017). "A stellar occultation by (486958) 2014 MU69: results from the 2017 July 17 portable telescope campaign". 504.03. https://dps49.abstractcentral.com/s1agxt/com.scholarone.s1agxt.s1agxt/S1A.html?&a=3987&b=1593989&c=43467&d=17&e=36573917&f=17&g=null&h=BROWSE_THE_PROGRAM&i=N&j=N&k=N&l=Y&m=Ni8N2nyNme3AGxIoteIxc0ieCYQ&r=ASjv5PkA6REkbiGTKaRPqg**.c027vkqs1as_ac&n=0&o=1502361552130&q=Y&p=https://dps49.abstractcentral.com&x=Y&z=.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (12 December 2017). "New Horizons strikes distant gold". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-42333783. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 Green, Jim (December 12, 2017). "New Horizons Explores the Kuiper Belt". 2017 American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting in New Orleans: 12-15. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/Press-Conferences/December-12-2017.php. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "New Horizons team prepares for stellar occultation ahead of Ultima Thule flyby". Space Daily. http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/New_Horizons_team_prepares_for_stellar_occultation_ahead_of_Ultima_Thule_flyby_999.html.

- ↑ "AFIPS participation to NASA expedition in Senegal". 2018. https://africapss.org/research/afips-participation-to-nasa-expedition-in-senegal/.

- ↑ "New Horizons Team Reports Initial Success in Observing Ultima Thule". JHUAPL. 4 August 2018. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20180804.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Bill Keeter (6 September 2018). "New Horizons Team Successfully Observes Next Target, Sets the Stage for Ultima Thule Flyby". NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/new-horizons-team-successfully-observes-next-target-sets-the-stage-for-ultima-thule-flyby.

- ↑ Buie, Marc (9 February 2018). "New Horizons support observations for 2014MU69 encounter - HST Proposal 15450". NASA. https://archive.stsci.edu/proposal_search.php?id=15450&mission=hst.

- ↑ Buie, M.; Porter, S. B.; Verbiscer, A.; Leiva, R.; Keeney, B. A.; Tsang, C.; Baratoux, D.; Skrutskie, M. et al. (26 October 2018). "Pre-encounter update on (486958) 2014MU69 and occultation results from 2017 and 2018". 50th Meeting of the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences. 509.06. https://aas.org/meetings/dps50. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ "Maneuver Moves New Horizons Spacecraft toward Next Potential Target". 23 October 2015. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20151023. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "New Horizons Continues Toward Potential Kuiper Belt Target". 26 October 2015. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20151026b. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "On Track: New Horizons Carries Out Third KBO Targeting Maneuver". 29 October 2015. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20151029. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Asteroid 2014 MU69". The Sky Live. http://theskylive.com/planetarium?obj=2014mu69&date=2019-01-01&h=00&m=00. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ "Ultima in View". 2018-08-28. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20180828. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ↑ "New Horizons Files Flight Plan for 2019 Flyby". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. 6 September 2017. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20170906.

- ↑ "Ultima in View: NASA’s New Horizons Makes First Detection of Kuiper Belt Flyby Target". NASA. 28 August 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/ultima-in-view-nasa-s-new-horizons-makes-first-detection-of-kuiper-belt-flyby-target.

- ↑ "JPL Horizons". JPL. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons.cgi.

External links

- "Pluto probe gets new assignment", Amanda Barnett, CNN, 28 August 2015

- (486958) 2014 MU69 at the JPL Small-Body Database