Astronomy:Nu Octantis

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Octans |

| Right ascension | 21h 41m 28.64977s[1] |

| Declination | −77° 23′ 24.1563″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.73[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| A | |

| Evolutionary stage | Subgiant[3] |

| Spectral type | K1IV[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.89[4] |

| B−V color index | +1.00[4] |

| B | |

| Evolutionary stage | white dwarf[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +34.40[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +66.41[1] mas/yr Dec.: −239.10[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 45.25 ± 0.25[6] mas |

| Distance | 73.5±0.68 ly (22.54±0.21 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 2.3±0.16[7] |

| Orbit[3] | |

| Period (P) | 1050.74+0.20 −0.10 days |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 2.61±0.03 AU |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.2366±0.0003 |

| Inclination (i) | 71.8+0.7 −0.6° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 86.5±0.3° |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 74.88+0.06 −0.14° |

| Semi-amplitude (K2) (secondary) | 7.0648+0.0050 −0.0009 km/s |

| Details[3] | |

| Nu Octantis A | |

| Mass | 1.57±0.06 M☉ |

| Radius | 5.04±0.10 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 13.2±0.3 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.23+0.02 −0.03 cgs |

| Temperature | 4,811.0±4.2[8] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | +0.18±0.04[9] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 2.0[9] km/s |

| Age | 2.70±0.35 Gyr |

| Nu Octantis B | |

| Mass | 0.57±0.01 M☉ |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Exoplanet Archive | Oct data |

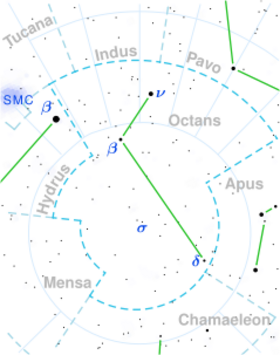

ν Octantis, Latinised as Nu Octantis, is a binary star in the constellation of Octans. Unusually for having such a late greek letter in its name, it is the brightest star in this faint constellation at apparent magnitude +3.7. It is located at 22.54 parsecs (73.5 light-years) from Earth, and is moving away at a radial velocity of +34.4 km/s. The primary star has an exoplanet whose orbit lies halfway between both stars.

Characteristics

This is a spectroscopic binary system,[11] meaning the binarity was inferred from periodic Doppler shifts in the spectral lines, which correspond to the motion of the stars.[12] Both stars take 1,050 days (2.9 years) to complete an orbit around each other, being separated by a semi-major axis of 2.61 astronomical units at a somewhat elliptical orbit.[3]

The primary has a spectral type of K1IV, with the luminosity class IV indicating that it is a subgiant star that has fused up all the hydrogen at its core and has expanded. Nu Octantis A has 1.57 times the mass of the Sun, but has expanded to 5.04 times the radius of the Sun.[9] Its photosphere has cooled to an effective temperature of 4,811 K[8] and now is radiating 13.2 times as much luminosity as the Sun.[3]

The secondary star is a white dwarf with 0.57 times the mass of the Sun. When it was on the main sequence, it had a mass of 2.36+0.13

−0.15 M☉ and was closer to its primary, at 1.31±0.07 AU. When it evolved to a red giant, and then to a white dwarf, it lost most of its mass, thus increasing the orbital separation. The primary star accreted about 0.2 M☉ from the secondary during this period.[3]

Nu Octantis is unusual on that its Bayer designation would suggest it is one of the faintest stars in the constellation, but is actually the brightest, over one magnitude brighter than Alpha Octantis. It seems that Lacaille (who lettered the Bayer stars in Octans) believed that Nu Octantis was a double star (like Mu Octantis) of small angular separation, rather than a single bright star.[13]

Planetary system

In 2009, the system was hypothesised to contain a superjovian exoplanet based on variations in the radial velocity.[6] A prograde solution was quickly ruled out[14] but a retrograde solution remains a possibility, although a study posited that it may instead be due to the secondary star being itself a close binary,[15] since the formation of a planet in such a system would be difficult due to gravitational perturbations.[16] Further evidence ruling out a stellar variability and favouring the existence of the planet was gathered by 2021.[7] With new radial velocity measurements, a study in 2025 confirmed the planet's existence.[3]

The binary components in the Nu Octantis system were initially separated by 1.3 AU, which overlap with the current orbital separation of the planet. Therefore, the planet did not form in its current orbit, but either migrated from a longer, circumbinary orbit, or originated from a protoplanetary disc that formed after the death of the white dwarf's progenitor.[3]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 2.19±0.11 MJ | 1.24±0.02 | 402.4+7.7 −6.0 |

0.195+0.050 −0.037 |

108.2° | — |

See also

- Gamma Cephei and Nu2 Canis Majoris, another similar-sized giant stars hosting a jovian planet

- Beta Hydri

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V. Vizier catalog entry

- ↑ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters 38 (5): 331. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. Bibcode: 2012AstL...38..331A. Vizier catalog entry

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Cheng, Ho Wan; Trifonov, Trifon; Lee, Man Hoi; Cantalloube, Faustine; Reffert, Sabine; Ramm, David; Quirrenbach, Andreas (May 2025). "A retrograde planet in a tight binary star system with a white dwarf" (in en). Nature 641 (8064): 866–870. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09006-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 40399630. Bibcode: 2025Natur.641..866C. https://rdcu.be/enkbR.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mallama, A. (2014). "Sloan Magnitudes for the Brightest Stars". The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers 42 (2): 443. Bibcode: 2014JAVSO..42..443M.Vizier catalog entry

- ↑ Wilson, R. E. (1953). "General Catalogue of Stellar Radial Velocities". Carnegie Institute Washington D.C. Publication (Carnegie Institution for Science). Bibcode: 1953GCRV..C......0W.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ramm, D. J.; Pourbaix, D.; Hearnshaw, J. B.; Komonjinda, S. (April 2009). "Spectroscopic orbits for K giants β Reticuli and ν Octantis: what is causing a low-amplitude radial velocity resonant perturbation in ν Oct?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 394 (3): 1695–1710. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14459.x. Bibcode: 2009MNRAS.394.1695R.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ramm, D J; Robertson, P et al. (2021). "A photospheric and chromospheric activity analysis of the quiescent retrograde-planet host ν Octantis A". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 502 (2): 2793–2806. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab078.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ramm, D. J. (2015-06-01). "Line-depth-ratio temperatures for the close binary ν Octantis: new evidence supporting the conjectured circumstellar retrograde planet" (in en). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 449 (4): 4428–4442. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv533. ISSN 0035-8711. Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.449.4428R.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ramm, D. J. (2016). "The conjectured S-type retrograde planet in ν Octantis: more evidence including four years of iodine-cell radial velocities". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 460 (4): 3706–3719. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1106. Bibcode: 2016MNRAS.460.3706R.

- ↑ "* nu. Oct". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=%2A+nu.+Oct.

- ↑ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (2): 869–879. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.389..869E.

- ↑ Struve, Otto; Huang, Su Shu (1958). Flügge, S.. ed (in en). Spectroscopic Binaries. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 243–273. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45906-1_8. ISBN 978-3-642-45906-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45906-1_8. Retrieved 2025-05-26.

- ↑ Lynn, W. T. (April 1911). "The constellation Octans" (in en). The Observatory 34: 160. ISSN 0029-7704. Bibcode: 1911Obs....34..160L. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1911Obs....34..160L/abstract.

- ↑ Eberle, J.; Cuntz, M. (October 2010). "On the reality of the suggested planet in the ν Octantis system". The Astrophysical Journal 721 (2): L168–L171. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/721/2/L168. Bibcode: 2010ApJ...721L.168E.

- ↑ Morais, M. H. M.; Correia, A. C. M. (February 2012). "Precession due to a close binary system: an alternative explanation for ν-Octantis?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 419 (4): 3447–3456. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19986.x. Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.419.3447M.

- ↑ Gozdziewski, K.; Slonina, M.; Migaszewski, C.; Rozenkiewicz, A. (March 2013). "Testing a hypothesis of the ν Octantis planetary system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 430 (1): 533–545. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts652. Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.430..533G.

|