Biology:Basal body

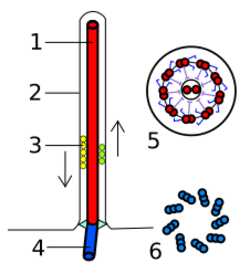

A basal body (synonymous with basal granule, kinetosome, and in older cytological literature with blepharoplast) is a protein structure found at the base of a eukaryotic undulipodium (cilium or flagellum). The basal body was named by Theodor Wilhelm Engelmann in 1880.[1][2] It is formed from a centriole and several additional protein structures, and is, essentially, a modified centriole.[3][4] The basal body serves as a nucleation site for the growth of the axoneme microtubules. Centrioles, from which basal bodies are derived, act as anchoring sites for proteins that in turn anchor microtubules, and are known as the microtubule organizing center (MTOC). These microtubules provide structure and facilitate movement of vesicles and organelles within many eukaryotic cells.

Assembly, structure

Cilia and basal bodies form during quiescence or the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Before the cell enters G1 phase, i.e. before the formation of the cilium, the mother centriole serves as a component of the centrosome.

In cells that are destined to have only one primary cilium, the mother centriole differentiates into the basal body upon entry into G1 or quiescence. Thus, the basal body in such a cell is derived from the centriole. The basal body differs from the mother centriole in at least 2 aspects. First, basal bodies have basal feet, which are anchored to cytoplasmic microtubules and are necessary for polarized alignment of the cilium. Second, basal bodies have pinwheel-shaped transition fibers that originate from the appendages of mother centriole.[5]

In multiciliated cells, however, in many cases basal bodies are not made from centrioles but are generated de novo from a special protein structure called the deuterosome.[6]

Function

During cell cycle dormancy, basal bodies organize primary cilia and reside at the cell cortex in proximity to plasma membrane. On cell cycle entry, cilia resorb and the basal body migrates to the nucleus where it functions to organize centrosomes. Centrioles, basal bodies, and cilia are important for mitosis, polarity, cell division, protein trafficking, signaling, motility and sensation.[7]

Mutations in proteins that localize to basal bodies are associated with several human ciliary diseases, including Bardet–Biedl syndrome,[8] orofaciodigital syndrome,[9][10] Joubert syndrome,[11] cone-rod dystrophy,[12][13] Meckel syndrome,[14] and nephronophthisis.[15]

Regulation of basal body production and spatial orientation is a function of the nucleotide-binding domain of γ-tubulin.[16]

Plants lack centrioles and only lower plants (such as mosses and ferns) with motile sperm have flagella and basal bodies.[17]

References

- ↑ Engelmann, T. W. (1880). Zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Flimmerzellen. Pflugers Arch. 23, 505–535.

- ↑ Bloodgood, R. A. (2009). "From Central to Rudimentary to Primary: The History of an Underappreciated Organelle Whose Time Has Come.The Primary Cilium". Primary Cilia. Methods in Cell Biology. 94. pp. 3–52. doi:10.1016/S0091-679X(08)94001-2. ISBN 9780123750242.

- ↑ Schrøder, Jacob M.; Larsen, Jesper; Komarova, Yulia; Akhmanova, Anna; Thorsteinsson, Rikke I.; Grigoriev, Ilya; Manguso, Robert; Christensen, Søren T. et al. (2011). "EB1 and EB3 promote cilia biogenesis by several centrosome-related mechanisms". Journal of Cell Science 124 (15): 2539–2551. doi:10.1242/jcs.085852. PMID 21768326.

- ↑ Benjamin Lewin (2007). Cells. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 359. ISBN 978-0-7637-3905-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=2VEGC8j9g9wC&pg=PA359. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ↑ Kim, S.; Dynlacht, B. D. (2013). "Assembling a primary cilium". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 25 (4): 506–511. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.011. PMID 23747070.

- ↑ Klos Dehring, D. A.; Vladar, E. K.; Werner, M. E.; Mitchell, J. W.; Hwang, P.; Mitchell, B. J. (2013). "Deuterosome-mediated centriole biogenesis". Developmental Cell 27 (1): 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.021. PMID 24075808.

- ↑ Pearson, C. G.; Giddings Jr, T. H.; Winey, M. (2009). "Basal body components exhibit differential protein dynamics during nascent basal body assembly". Molecular Biology of the Cell 20 (3): 904–914. doi:10.1091/mbc.e08-08-0835. PMID 19056680.

- ↑ Ansley, S. J.; Badano, J. L.; Blacque, O. E.; Hill, J.; Hoskins, B. E.; Leitch, C. C.; Kim, J. C.; Ross, A. J. et al. (2003). "Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome". Nature 425 (6958): 628–633. doi:10.1038/nature02030. PMID 14520415. Bibcode: 2003Natur.425..628A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14520415/.

- ↑ Ferrante, M. I.; Zullo, A.; Barra, A.; Bimonte, S.; Messaddeq, N.; Studer, M.; Dollé, P.; Franco, B. (2006). "Oral-facial-digital type I protein is required for primary cilia formation and left-right axis specification". Nature Genetics 38 (1): 112–117. doi:10.1038/ng1684. PMID 16311594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16311594/.

- ↑ Romio, L.; Fry, A. M.; Winyard, P. J.; Malcolm, S.; Woolf, A. S.; Feather, S. A. (2004). "OFD1 is a centrosomal/Basal body protein expressed during mesenchymal-epithelial transition in human nephrogenesis". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 15 (10): 2556–2568. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000140220.46477.5C. PMID 15466260.

- ↑ Arts, H. H.; Doherty, D.; Van Beersum, S. E.; Parisi, M. A.; Letteboer, S. J.; Gorden, N. T.; Peters, T. A.; Märker, T. et al. (2007). "Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome". Nature Genetics 39 (7): 882–888. doi:10.1038/ng2069. PMID 17558407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17558407/.

- ↑ Kobayashi, A.; Higashide, T.; Hamasaki, D.; Kubota, S.; Sakuma, H.; An, W.; Fujimaki, T.; McLaren, M. J. et al. (2000). "HRG4 (UNC119) mutation found in cone-rod dystrophy causes retinal degeneration in a transgenic model". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 41 (11): 3268–3277. PMID 11006213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11006213/.

- ↑ Shu, X.; Fry, A. M.; Tulloch, B.; Manson, F. D.; Crabb, J. W.; Khanna, H.; Faragher, A. J.; Lennon, A. et al. (2005). "RPGR ORF15 isoform co-localizes with RPGRIP1 at centrioles and basal bodies and interacts with nucleophosmin". Human Molecular Genetics 14 (9): 1183–1197. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi129. PMID 15772089.

- ↑ Kyttälä, M.; Tallila, J.; Salonen, R.; Kopra, O.; Kohlschmidt, N.; Paavola-Sakki, P.; Peltonen, L.; Kestilä, M. (2006). "MKS1, encoding a component of the flagellar apparatus basal body proteome, is mutated in Meckel syndrome". Nature Genetics 38 (2): 155–157. doi:10.1038/ng1714. PMID 16415886. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16415886/.

- ↑ Winkelbauer, M. E.; Schafer, J. C.; Haycraft, C. J.; Swoboda, P.; Yoder, B. K. (2005). "The C. Elegans homologs of nephrocystin-1 and nephrocystin-4 are cilia transition zone proteins involved in chemosensory perception". Journal of Cell Science 118 (Pt 23): 5575–5587. doi:10.1242/jcs.02665. PMID 16291722. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16291722/.

- ↑ Shang, Y.; Tsao, C. C.; Gorovsky, M. A. (2005). "Mutational analyses reveal a novel function of the nucleotide-binding domain of gamma-tubulin in the regulation of basal body biogenesis". The Journal of Cell Biology 171 (6): 1035–1044. doi:10.1083/jcb.200508184. PMID 16344310.

- ↑ Philip E. Pack, Ph.D., Cliff's Notes: AP Biology 4th edition.

External links

- Histology image: 21804loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Ultrastructure of the Cell: ciliated epithelium, cilia and basal bodies"

|