Biology:Separase

Generic protein structure example |

Separase, also known as separin, is a cysteine protease responsible for triggering anaphase by hydrolysing cohesin, which is the protein responsible for binding sister chromatids during the early stage of anaphase.[1] In humans, separin is encoded by the ESPL1 gene.[2]

History

In S. cerevisiae, separase is encoded by the esp1 gene. Esp1 was discovered by Kim Nasmyth and coworkers in 1998.[3][4] In 2021, structures of human separase were determined in complex with either securin or CDK1-cyclin B1-CKS1 using cryo-EM by scientists of the University of Geneva.[5]

Function

Stable cohesion between sister chromatids before anaphase and their timely separation during anaphase are critical for cell division and chromosome inheritance. In vertebrates, sister chromatid cohesion is released in 2 steps via distinct mechanisms. The first step involves phosphorylation of STAG1 or STAG2 in the cohesin complex. The second step involves cleavage of the cohesin subunit SCC1 (RAD21) by separase, which initiates the final separation of sister chromatids.[7]

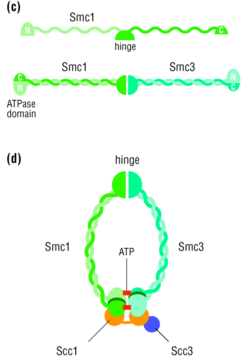

In S. cerevisiae, Esp1 is coded by ESP1 and is regulated by the securin Pds1. The two sister chromatids are initially bound together by the cohesin complex until the beginning of anaphase, at which point the mitotic spindle pulls the two sister chromatids apart, leaving each of the two daughter cells with an equivalent number of sister chromatids. The proteins that bind the two sister chromatids, disallowing any premature sister chromatid separation, are a part of the cohesin protein family. One of these cohesin proteins crucial for sister chromatid cohesion is Scc1. Esp1 is a separase protein that cleaves the cohesin subunit Scc1 (RAD21), allowing sister chromatids to separate at the onset of anaphase during mitosis.[4]

Regulation

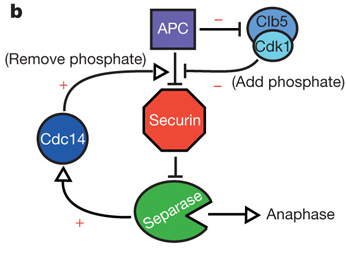

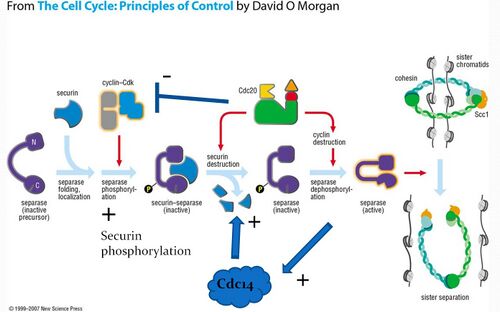

When the cell is not dividing, separase is prevented from cleaving cohesin through its association with either securin or upon phosphorylation of a specific serine residue in separase by the cyclin-CDK complex. Separase phosphorylation leads to a stable association with CDK1-cyclin B1. Securin or CDK1-cyclin B binding is mutually exclusive. In both complexes, separase is inhibited by pseudosubstrate motifs that block substrate binding at the catalytic site and at nearby docking sites. However, while securin contains its own pseudosubstrate motifs to occlude substrate binding, the CDK1–cyclin B complex inhibits separase by rigidifying pseudosubstrate motifs from flexible loops in separase itself, leading to an auto-inhibition of the proteolytic activity of separase.[5] Regulation through these distinct binding partners provides two layers of negative regulation to prevent inappropriate cohesin cleavage. Note that separase cannot function without initially forming the securin-separase complex in most organisms. This is because securin helps properly fold separase into the functional conformation. However, yeast does not appear to require securin to form functional separase because anaphase occurs in yeast even with a securin deletion.[6]

On the signal for anaphase, securin is ubiquitinated and hydrolysed, releasing separase for dephosphorylation by the APC-Cdc20 complex. Active separase can then cleave Scc1 for release of the sister chromatids.

Separase initiates the activation of Cdc14 in early anaphase[9] and Cdc14 has been found to dephosphorylate securin, thereby increasing its efficiency as a substrate for degradation. The presence of this positive feedback loop offers a potential mechanism for giving anaphase a more switch-like behavior.[8]

References

- ↑ "ESPL1 - Separin - Homo sapiens (Human) - ESPL1 gene & protein". 2010-10-05. https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q14674.

- ↑ "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. V. The coding sequences of 40 new genes (KIAA0161-KIAA0200) deduced by analysis of cDNA clones from human cell line KG-1". DNA Research 3 (1): 17–24. February 1996. doi:10.1093/dnares/3.1.17. PMID 8724849.

- ↑ "An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast". Cell 93 (6): 1067–1076. June 1998. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81211-8. PMID 9635435.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1". Nature 400 (6739): 37–42. July 1999. doi:10.1038/21831. PMID 10403247. Bibcode: 1999Natur.400...37U.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Structural basis of human separase regulation by securin and CDK1-cyclin B1". Nature 596 (7870): 138–142. August 2021. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03764-0. PMID 34290405.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The cell cycle: principles of control. London: Published by New Science Press in association with Oxford University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-87893-508-6.

- ↑ "Separase is recruited to mitotic chromosomes to dissolve sister chromatid cohesion in a DNA-dependent manner". Cell 137 (1): 123–132. April 2009. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.040. PMID 19345191.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Positive feedback sharpens the anaphase switch". Nature 454 (7202): 353–357. July 2008. doi:10.1038/nature07050. PMID 18552837. Bibcode: 2008Natur.454..353H.

- ↑ "Separase, polo kinase, the kinetochore protein Slk19, and Spo12 function in a network that controls Cdc14 localization during early anaphase". Cell 108 (2): 207–220. January 2002. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00618-9. PMID 11832211.

Further reading

- "Requirement for ESP1 in the nuclear division of Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Molecular Biology of the Cell 3 (12): 1443–1454. December 1992. doi:10.1091/mbc.3.12.1443. PMID 1493337.

- "An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast". Cell 93 (6): 1067–1076. June 1998. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81211-8. PMID 9635435.

- "A novel role of the budding yeast separin Esp1 in anaphase spindle elongation: evidence that proper spindle association of Esp1 is regulated by Pds1". The Journal of Cell Biology 152 (1): 27–40. January 2001. doi:10.1083/jcb.152.1.27. PMID 11149918.

- "Haploinsufficiency of cohesin protease, Separase, promotes regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells in mice". Stem Cells 38 (12): 1624–1636. September 2020. doi:10.1002/stem.3280. PMID 32997844.

External links

- separase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20041117073907/http://ncbi.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Nucleotide

- Video by David Morgan explaining action of securin and separin (in MP4 format): http://media.hhmi.org/ibio/morgan/morgan_3.mp4

- and in other formats: [1]

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

|