Biology:Two-component regulatory system

| Histidine kinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | His_kinase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF06580 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR016380 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 281 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 5iji | ||||||||

| |||||||||

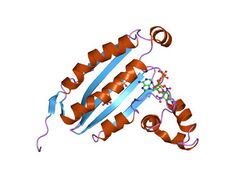

| His Kinase A (phospho-acceptor) domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

solved structure of the homodimeric domain of EnvZ from Escherichia coli by multi-dimensional NMR. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | HisKA | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00512 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0025 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003661 | ||||||||

| SMART | HisKA | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1b3q / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Histidine kinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | HisKA_2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF07568 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0025 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR011495 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Histidine kinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | HisKA_3 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF07730 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0025 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR011712 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Signal transducing histidine kinase, homodimeric domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

structure of CheA domain p4 in complex with TNP-ATP | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | H-kinase_dim | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02895 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR004105 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1b3q / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Histidine kinase N terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | HisK_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09385 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR018984 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Osmosensitive K+ channel His kinase sensor domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | KdpD | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02702 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003852 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In the field of molecular biology, a two-component regulatory system serves as a basic stimulus-response coupling mechanism to allow organisms to sense and respond to changes in many different environmental conditions.[1] Two-component systems typically consist of a membrane-bound histidine kinase that senses a specific environmental stimulus and a corresponding response regulator that mediates the cellular response, mostly through differential expression of target genes.[2] Although two-component signaling systems are found in all domains of life, they are most common by far in bacteria, particularly in Gram-negative and cyanobacteria; both histidine kinases and response regulators are among the largest gene families in bacteria.[3] They are much less common in archaea and eukaryotes; although they do appear in yeasts, filamentous fungi, and slime molds, and are common in plants,[1] two-component systems have been described as "conspicuously absent" from animals.[3]

Mechanism

Two-component systems accomplish signal transduction through the phosphorylation of a response regulator (RR) by a histidine kinase (HK). Histidine kinases are typically homodimeric transmembrane proteins containing a histidine phosphotransfer domain and an ATP binding domain, though there are reported examples of histidine kinases in the atypical HWE and HisKA2 families that are not homodimers.[4] Response regulators may consist only of a receiver domain, but usually are multi-domain proteins with a receiver domain and at least one effector or output domain, often involved in DNA binding.[3] Upon detecting a particular change in the extracellular environment, the HK performs an autophosphorylation reaction, transferring a phosphoryl group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to a specific histidine residue. The cognate response regulator (RR) then catalyzes the transfer of the phosphoryl group to an aspartate residue on the response regulator's receiver domain.[5][6] This typically triggers a conformational change that activates the RR's effector domain, which in turn produces the cellular response to the signal, usually by stimulating (or repressing) expression of target genes.[3]

Many HKs are bifunctional and possess phosphatase activity against their cognate response regulators, so that their signaling output reflects a balance between their kinase and phosphatase activities. Many response regulators also auto-dephosphorylate,[7] and the relatively labile phosphoaspartate can also be hydrolyzed non-enzymatically.[1] The overall level of phosphorylation of the response regulator ultimately controls its activity.[1][8]

Phosphorelays

Some histidine kinases are hybrids that contain an internal receiver domain. In these cases, a hybrid HK autophosphorylates and then transfers the phosphoryl group to its own internal receiver domain, rather than to a separate RR protein. The phosphoryl group is then shuttled to histidine phosphotransferase (HPT) and subsequently to a terminal RR, which can evoke the desired response.[9][10] This system is called a phosphorelay. Almost 25% of bacterial HKs are of the hybrid type, as are the large majority of eukaryotic HKs.[3]

Function

Two-component signal transduction systems enable bacteria to sense, respond, and adapt to a wide range of environments, stressors, and growth conditions.[11] These pathways have been adapted to respond to a wide variety of stimuli, including nutrients, cellular redox state, changes in osmolarity, quorum signals, antibiotics, temperature, chemoattractants, pH and more.[12][13] The average number of two-component systems in a bacterial genome has been estimated as around 30,[14] or about 1–2% of a prokaryote's genome.[15] A few bacteria have none at all – typically endosymbionts and pathogens – and others contain over 200.[16][17] All such systems must be closely regulated to prevent cross-talk, which is rare in vivo.[18]

In Escherichia coli, the osmoregulatory EnvZ/OmpR two-component system controls the differential expression of the outer membrane porin proteins OmpF and OmpC.[19] The KdpD sensor kinase proteins regulate the kdpFABC operon responsible for potassium transport in bacteria including E. coli and Clostridium acetobutylicum.[20] The N-terminal domain of this protein forms part of the cytoplasmic region of the protein, which may be the sensor domain responsible for sensing turgor pressure.[21]

Histidine kinases

Signal transducing histidine kinases are the key elements in two-component signal transduction systems.[22][23] Examples of histidine kinases are EnvZ, which plays a central role in osmoregulation,[24] and CheA, which plays a central role in the chemotaxis system.[25] Histidine kinases usually have an N-terminal ligand-binding domain and a C-terminal kinase domain, but other domains may also be present. The kinase domain is responsible for the autophosphorylation of the histidine with ATP, the phosphotransfer from the kinase to an aspartate of the response regulator, and (with bifunctional enzymes) the phosphotransfer from aspartyl phosphate to water.[26] The kinase core has a unique fold, distinct from that of the Ser/Thr/Tyr kinase superfamily.

HKs can be roughly divided into two classes: orthodox and hybrid kinases.[27][28] Most orthodox HKs, typified by the E. coli EnvZ protein, function as periplasmic membrane receptors and have a signal peptide and transmembrane segment(s) that separate the protein into a periplasmic N-terminal sensing domain and a highly conserved cytoplasmic C-terminal kinase core. Members of this family, however, have an integral membrane sensor domain. Not all orthodox kinases are membrane bound, e.g., the nitrogen regulatory kinase NtrB (GlnL) is a soluble cytoplasmic HK.[6] Hybrid kinases contain multiple phosphodonor and phosphoacceptor sites and use multi-step phospho-relay schemes instead of promoting a single phosphoryl transfer. In addition to the sensor domain and kinase core, they contain a CheY-like receiver domain and a His-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) domain.

Evolution

The number of two-component systems present in a bacterial genome is highly correlated with genome size as well as ecological niche; bacteria that occupy niches with frequent environmental fluctuations possess more histidine kinases and response regulators.[3][29] New two-component systems may arise by gene duplication or by lateral gene transfer, and the relative rates of each process vary dramatically across bacterial species.[30] In most cases, response regulator genes are located in the same operon as their cognate histidine kinase;[3] lateral gene transfers are more likely to preserve operon structure than gene duplications.[30]

In eukaryotes

Two-component systems are rare in eukaryotes. They appear in yeasts, filamentous fungi, and slime molds, and are relatively common in plants, but have been described as "conspicuously absent" from animals.[3] Two-component systems in eukaryotes likely originate from lateral gene transfer, often from endosymbiotic organelles, and are typically of the hybrid kinase phosphorelay type.[3] For example, in the yeast Candida albicans, genes found in the nuclear genome likely originated from endosymbiosis and remain targeted to the mitochondria.[31] Two-component systems are well-integrated into developmental signaling pathways in plants, but the genes probably originated from lateral gene transfer from chloroplasts.[3] An example is the chloroplast sensor kinase (CSK) gene in Arabidopsis thaliana, derived from chloroplasts but now integrated into the nuclear genome. CSK function provides a redox-based regulatory system that couples photosynthesis to chloroplast gene expression; this observation has been described as a key prediction of the CoRR hypothesis, which aims to explain the retention of genes encoded by endosymbiotic organelles.[32][33]

It is unclear why canonical two-component systems are rare in eukaryotes, with many similar functions having been taken over by signaling systems based on serine, threonine, or tyrosine kinases; it has been speculated that the chemical instability of phosphoaspartate is responsible, and that increased stability is needed to transduce signals in the more complex eukaryotic cell.[3] Notably, cross-talk between signaling mechanisms is very common in eukaryotic signaling systems but rare in bacterial two-component systems.[34]

Bioinformatics

Because of their sequence similarity and operon structure, many two-component systems – particularly histidine kinases – are relatively easy to identify through bioinformatics analysis. (By contrast, eukaryotic kinases are typically easily identified, but they are not easily paired with their substrates.)[3] A database of prokaryotic two-component systems called P2CS has been compiled to document and classify known examples, and in some cases to make predictions about the cognates of "orphan" histidine kinase or response regulator proteins that are genetically unlinked to a partner.[35][36]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Two-component signal transduction". Annual Review of Biochemistry 69 (1): 183–215. 2000. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. PMID 10966457.

- ↑ "Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 70 (4): 910–38. Dec 2006. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00020-06. PMID 17158704.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 "Evolution of two-component signal transduction systems". Annual Review of Microbiology 66: 325–47. 2012. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150039. PMID 22746333.

- ↑ Herrou, J; Crosson, S; Fiebig, A (Feb 2017). "Structure and function of HWE/HisKA2-family sensor histidine kinases". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 36: 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.008. PMID 28193573.

- ↑ "Identification of the site of phosphorylation of the chemotaxis response regulator protein, CheY". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 264 (36): 21770–8. Dec 1989. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)88250-7. PMID 2689446.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Phosphorylation site of NtrC, a protein phosphatase whose covalent intermediate activates transcription". Journal of Bacteriology 174 (15): 5117–22. Aug 1992. doi:10.1128/jb.174.15.5117-5122.1992. PMID 1321122.

- ↑ "Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 26 (6): 369–76. Jun 2001. doi:10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01852-7. PMID 11406410.

- ↑ "Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria". Microbiological Reviews 53 (4): 450–90. Dec 1989. doi:10.1128/MMBR.53.4.450-490.1989. PMID 2556636.

- ↑ "Molecular recognition of bacterial phosphorelay proteins". Current Opinion in Microbiology 5 (2): 142–8. Apr 2002. doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00305-3. PMID 11934609.

- ↑ "Keeping signals straight in phosphorelay signal transduction". Journal of Bacteriology 183 (17): 4941–9. Sep 2001. doi:10.1128/jb.183.17.4941-4949.2001. PMID 11489844.

- ↑ "Two-component signal transduction pathways regulating growth and cell cycle progression in a bacterium: a system-level analysis". PLOS Biology 3 (10): e334. Oct 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030334. PMID 16176121.

- ↑ "Histidine protein kinases: key signal transducers outside the animal kingdom". Genome Biology 3 (10): REVIEWS3013. Sep 2002. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-reviews3013. PMID 12372152.

- ↑ "Focus on phosphohistidine". Amino Acids 32 (1): 145–56. Jan 2007. doi:10.1007/s00726-006-0443-6. PMID 17103118.

- ↑ Schaller, GE; Shiu, SH; Armitage, JP (10 May 2011). "Two-component systems and their co-option for eukaryotic signal transduction.". Current Biology 21 (9): R320–30. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.045. PMID 21549954.

- ↑ Salvado, B; Vilaprinyo, E; Sorribas, A; Alves, R (2015). "A survey of HK, HPt, and RR domains and their organization in two-component systems and phosphorelay proteins of organisms with fully sequenced genomes.". PeerJ 3: e1183. doi:10.7717/peerj.1183. PMID 26339559.

- ↑ Wuichet, K; Cantwell, BJ; Zhulin, IB (April 2010). "Evolution and phyletic distribution of two-component signal transduction systems.". Current Opinion in Microbiology 13 (2): 219–25. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2009.12.011. PMID 20133179.

- ↑ Shi, X; Wegener-Feldbrügge, S; Huntley, S; Hamann, N; Hedderich, R; Søgaard-Andersen, L (January 2008). "Bioinformatics and experimental analysis of proteins of two-component systems in Myxococcus xanthus.". Journal of Bacteriology 190 (2): 613–24. doi:10.1128/jb.01502-07. PMID 17993514.

- ↑ "Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways". Annual Review of Genetics 41: 121–45. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170548. PMID 18076326.

- ↑ "Response-regulator phosphorylation and activation: a two-way street?". Trends in Microbiology 8 (4): 153–6. Apr 2000. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01707-8. PMID 10754569.

- ↑ "The kdp system of Clostridium acetobutylicum: cloning, sequencing, and transcriptional regulation in response to potassium concentration". Journal of Bacteriology 179 (14): 4501–12. Jul 1997. doi:10.1128/jb.179.14.4501-4512.1997. PMID 9226259.

- ↑ "KdpD and KdpE, proteins that control expression of the kdpABC operon, are members of the two-component sensor-effector class of regulators". Journal of Bacteriology 174 (7): 2152–9. Apr 1992. doi:10.1128/jb.174.7.2152-2159.1992. PMID 1532388.

- ↑ "Protein aspartate phosphatases control the output of two-component signal transduction systems". Trends in Genetics 12 (3): 97–101. Mar 1996. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(96)81420-X. PMID 8868347.

- ↑ "Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 26 (6): 369–76. Jun 2001. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01852-7. PMID 11406410.

- ↑ "Solution structure of the homodimeric core domain of Escherichia coli histidine kinase EnvZ". Nature Structural Biology 6 (8): 729–34. Aug 1999. doi:10.1038/11495. PMID 10426948.

- ↑ "Structure of CheA, a signal-transducing histidine kinase". Cell 96 (1): 131–41. Jan 1999. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80966-6. PMID 9989504.

- ↑ "Bacteriophytochromes: new tools for understanding phytochrome signal transduction". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 11 (6): 511–21. Dec 2000. doi:10.1006/scdb.2000.0206. PMID 11145881.

- ↑ "Protein histidine kinases and signal transduction in prokaryotes and eukaryotes". Trends in Genetics 10 (4): 133–8. Apr 1994. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(94)90215-1. PMID 8029829.

- ↑ "Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins". Annual Review of Genetics 26: 71–112. 1992. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. PMID 1482126.

- ↑ "Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations". Journal of Bacteriology 188 (12): 4169–82. Jun 2006. doi:10.1128/JB.01887-05. PMID 16740923.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The evolution of two-component systems in bacteria reveals different strategies for niche adaptation". PLOS Computational Biology 2 (11): e143. Nov 2006. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020143. PMID 17083272. Bibcode: 2006PLSCB...2..143A.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial two-component signaling systems in Candida albicans". Eukaryotic Cell 12 (6): 913–22. Jun 2013. doi:10.1128/EC.00048-13. PMID 23584995.

- ↑ "The ancestral symbiont sensor kinase CSK links photosynthesis with gene expression in chloroplasts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (29): 10061–6. Jul 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803928105. PMID 18632566. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10510061P.

- ↑ "Why chloroplasts and mitochondria retain their own genomes and genetic systems: Colocation for redox regulation of gene expression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (33): 10231–8. Aug 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500012112. PMID 26286985. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11210231A.

- ↑ "Crosstalk and the evolution of specificity in two-component signaling". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (15): 5550–5. Apr 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317178111. PMID 24706803. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111.5550R.

- ↑ "P2CS: a database of prokaryotic two-component systems". Nucleic Acids Research 39 (Database issue): D771–6. Jan 2011. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1023. PMID 21051349.

- ↑ "P2CS: updates of the prokaryotic two-component systems database". Nucleic Acids Research 43 (Database issue): D536–41. Jan 2015. doi:10.1093/nar/gku968. PMID 25324303.

External links

- http://www.p2cs.org: The Prokaryotic 2-Component Systems Database

|