Hectogon

| Regular hectogon | |

|---|---|

A regular hectogon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 100 |

| Schläfli symbol | {100}, t{50}, tt{25} |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D100), order 2×100 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | 176.4° |

| Dual polygon | Self |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

In geometry, a hectogon or hecatontagon or 100-gon[1][2] is a hundred-sided polygon.[3][4] The sum of all hectogon's interior angles are 17640 degrees.

Regular hectogon

A regular hectogon is represented by Schläfli symbol {100} and can be constructed as a truncated pentacontagon, t{50}, or a twice-truncated icosipentagon, tt{25}.

One interior angle in a regular hectogon is 1762⁄5°, meaning that one exterior angle would be 33⁄5°.

The area of a regular hectogon is (with t = edge length)

and its inradius is

The circumradius of a regular hectogon is

Because 100 = 22 × 52, the number of sides contains a repeated Fermat prime (the number 5). Thus the regular hectogon is not a constructible polygon.[5] Indeed, it is not even constructible with the use of an angle trisector, as the number of sides is neither a product of distinct Pierpont primes, nor a product of powers of two and three.[6] It is not known if the regular hectogon is neusis constructible.

However, a hectogon is constructible using an auxiliary curve such as an Archimedean spiral. A 72° angle is constructible with compass and straightedge, so a possible approach to constructing one side of a hectogon is to construct a 72° angle using compass and straightedge, use an Archimedean spiral to construct a 14.4° angle, and bisect one of the 14.4° angles twice.

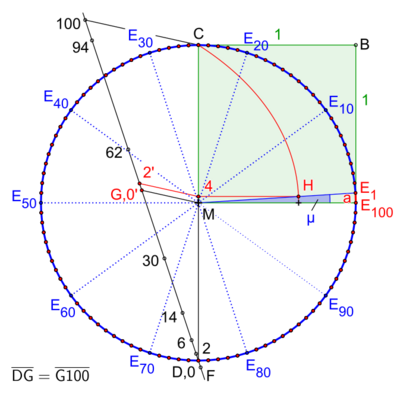

Exact construction with help the quadratrix of Hippias

Symmetry

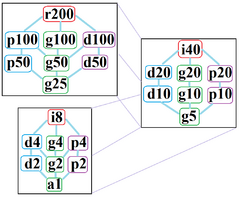

The regular hectogon has Dih100 dihedral symmetry, order 200, represented by 100 lines of reflection. Dih100 has 8 dihedral subgroups: (Dih50, Dih25), (Dih20, Dih10, Dih5), (Dih4, Dih2, and Dih1). It also has 9 more cyclic symmetries as subgroups: (Z100, Z50, Z25), (Z20, Z10, Z5), and (Z4, Z2, Z1), with Zn representing π/n radian rotational symmetry.

John Conway labels these lower symmetries with a letter and order of the symmetry follows the letter.[7] r200 represents full symmetry and a1 labels no symmetry. He gives d (diagonal) with mirror lines through vertices, p with mirror lines through edges (perpendicular), i with mirror lines through both vertices and edges, and g for rotational symmetry.

These lower symmetries allows degrees of freedom in defining irregular hectogons. Only the g100 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can seen as directed edges.

Dissection

Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into m(m-1)/2 parallelograms. [8] In particular this is true for regular polygons with evenly many sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. For the regular hectogon, m=50, it can be divided into 1225: 25 squares and 24 sets of 50 rhombs. This decomposition is based on a Petrie polygon projection of a 50-cube.

|

|

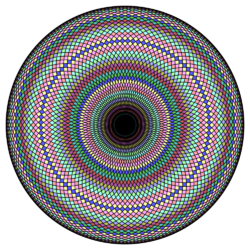

Hectogram

A hectogram is a 100-sided star polygon. There are 19 regular forms[9] given by Schläfli symbols {100/3}, {100/7}, {100/9}, {100/11}, {100/13}, {100/17}, {100/19}, {100/21}, {100/23}, {100/27}, {100/29}, {100/31}, {100/33}, {100/37}, {100/39}, {100/41}, {100/43}, {100/47}, and {100/49}, as well as 30 regular star figures with the same vertex configuration.

| Picture |  {100/3} |

{100/7} |

{100/11} |

{100/13} |

{100/17} |

{100/19} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interior angle | 169.2° | 154.8° | 140.4° | 133.2° | 118.8° | 111.6° |

| Picture |  {100/21} |

{100/23} |

{100/27} |

{100/29} |

{100/31} |

{100/37} |

| Interior angle | 104.4° | 97.2° | 82.8° | 75.6° | 68.4° | 46.8° |

| Picture |  {100/39} |

{100/41} |

{100/43} |

{100/47} |

{100/49} |

|

| Interior angle | 39.6° | 32.4° | 25.2° | 10.8° | 3.6° |

See also

References

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Gorini, Catherine A. (2009), The Facts on File Geometry Handbook, Infobase Publishing, p. 110, ISBN 9781438109572, https://books.google.com/books?id=PlYCcvgLJxYC&pg=PA110.

- ↑ The New Elements of Mathematics: Algebra and Geometry by Charles Sanders Peirce (1976), p.298

- ↑ Constructible Polygon

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-14. https://web.archive.org/web/20150714082609/http://www.math.iastate.edu/thesisarchive/MSM/EekhoffMSMSS07.pdf. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- ↑ The Symmetries of Things, Chapter 20

- ↑ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ↑ 19 = 50 cases - 1 (convex) - 10 (multiples of 5) - 25 (multiples of 2)+ 5 (multiples of 2 and 5)

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Hectogon". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Hectogon.html.

- Naming Polygons and Polyhedra

- hecatonagon