Indian numerals

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Indian numerals are the symbols representing numbers in India. These numerals are used in the context of the decimal Hindu–Arabic numeral system, and are distinct from, though related by descent to Arabic numerals.

Devanagari

Below is a list of the Indian numerals in their modern Devanagari form, the corresponding Western Arabic equivalents, their Hindi and Sanskrit pronunciation, and translations in some languages.[1]

| Modern Devanagari |

Western Arabic |

Words for the cardinal number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindi | Sanskrit (wordstem) |

Cognates in other Indo-European languages | |||

| Indo-Iranian | European | ||||

| ० | 0 | śūnya (शून्य) | śūnya (शून्य) | shunna/shunne (Nepali) shunno (Bengali, Sylheti) |

|

| १ | 1 | ek (एक) | eka (एक) | ek (Nepali) yek (Persian) æk (Bengali) ekh (Sylheti) |

eins (German) |

| २ | 2 | do (दो) | dvi (द्वि) | do (Persian) | dva (Russian) due (Italian) tveir (Old Norse) zwei (German) |

| ३ | 3 | tīn (तीन) | tri (त्रि) | tin (Bengali, Nepali, Sylheti) | tri (Russian) tre (Italian) three (English) drei (German) |

| ४ | 4 | cār (चार) | catur (चतुर्) | chahar (Persian) | katër (Albanian) quattro (Italian) četiri (Serbian) chetyre (Russian) ceathair (Irish Gaelic) vier (German) |

| ५ | 5 | [pā͂c] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 3: ͂) (help) (पाँच) | pañca (पञ्चन्) | panj (Persian) | pyat' (Russian) penki (Lithuanian) pięć (Polish) fünf (German) |

| ६ | 6 | chaḥ (छः) | ṣaṭh (षट्) | shesh (Persian) | shest' (Russian) seis (Spanish) seis (Portuguese) sechs (German) |

| ७ | 7 | sāt (सात) | sapta (सप्त) | saat (Nepali) shat (Bengali, Sylheti) |

sette (Italian) sept (French) sete (Portuguese) |

| ८ | 8 | āṭh (आठ) | aṣṭa (अष्ट) | hasht (Persian) | astoņi (Latvian) acht (German)

|

| ९ | 9 | nau (नौ) | nava (नव) | nau (Nepali) noh (Persian) noy (Bengali, Sylheti) |

naw (Welsh) nove (Italian, Portuguese) neun (German) nueve (Spanish, Asturian) |

Since Sanskrit is an Indo-European language, the words for numerals closely resemble those of Greek and Latin. The word "Shunya" for zero was translated into Arabic as "صفر" "sifr", meaning 'nothing' which became the term "zero" in many European languages from Medieval Latin, zephirum.[2]

Variants

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Devanagari digits shapes may vary depending on geographical area.[3][4]

| १ | common |

Nepali |

|---|---|---|

| ५ | "Bombay" variant |

"Calcutta" variant |

| ८ | "Bombay" variant |

"Calcutta" variant |

| ९ | common |

Nepali |

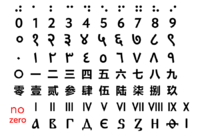

Other Indic scripts

The five Indian languages (Hindi, Marathi, Konkani, Nepali and Sanskrit itself) that have adapted the Devanagari script to their use also naturally employ the numeral symbols above; of course, the names for the numbers vary by language. The table below presents a listing of the symbols used in various modern Indian scripts in comparison to Western and Eastern Arabic numerals:

| Western Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Eastern Arabic | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ |

| Devanagari | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Northern | ||||||||||

| Gujarati | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Gurmukhi (Punjabi) |

੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Lepcha (Sikkim and Bhutan) |

| |||||||||

| Bengali-Assamese | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Odia | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Southern | ||||||||||

| Telugu | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Kannada | ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ |

| Tamil and Grantha | ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

| Malayalam | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

Tamil and Malayalam also have distinct forms for numerals 10, 100, 1000 as ௰, ௱, ௲ and ൰, ൱, ൲, respectively.

History

A decimal place system has been traced back to c. 500 in India. Before that epoch, the Brahmi numeral system was in use; that system did not encompass the concept of the place-value of numbers. Instead, Brahmi numerals included additional symbols for the tens, as well as separate symbols for hundred and thousand.

The Indian place-system numerals spread to neighboring Persia, where they were picked up by the conquering Arabs. In 662, Severus Sebokht - a Nestorian bishop living in Syria wrote:

I will omit all discussion of the science of the Indians ... of their subtle discoveries in astronomy — discoveries that are more ingenious than those of the Greeks and the Babylonians - and of their valuable methods of calculation which surpass description. I wish only to say that this computation is done by means of nine signs. If those who believe that because they speak Greek they have arrived at the limits of science would read the Indian texts they would be convinced even if a little late in the day that there are others who know something of value.[5]

The addition of zero as a tenth positional digit is documented from the 7th century by Brahmagupta, though the earlier Bakhshali Manuscript, written sometime before the 5th century, also included zero. But it is in Khmer numerals of modern Cambodia where the first extant material evidence of zero as a numerical figure, dating its use back to the seventh century, is found.[6]

As it was from the Arabs that the Europeans learned this system, the Europeans called them Arabic numerals; the Arabs refer to their numerals as Indian numerals. In academic circles they[which?] are called the Hindu–Arabic or Indo–Arabic numerals.

The significance of the development of the positional number system is probably best described by the French mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace (1749–1827) who wrote:

It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by the means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position, as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit, but its very simplicity, the great ease which it has lent to all computations, puts our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions, and we shall appreciate the grandeur of this achievement when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest minds produced by antiquity.

Tobias Dantzig[7] had this to say in Number:[8][9]

This long period of nearly five thousand years saw the rise and fall of many civilizations, each leaving behind a heritage of literature, art, philosophy, and religion. But what was the net achievement in the field of reckoning, the earliest art practiced by man? An inflexible numeration so crude as to make progress well nigh impossible, and a calculating device so limited in scope that even elementary calculations called for the services of an expert. [...] man used these devices for thousands of years [...] without contributing a single important idea to the system!

[...] even when compared with the slow growth of ideas during the Dark Ages, the history of reckoning presents a peculiar picture of desolate stagnation.

When viewed in this light, the achievements of the unknown Hindu, who some time in the first centuries of our era discovered the principle of position assumes the importance of a world event.

See also

- Western Arabic numerals

- Eastern Arabic numerals

- Bengali-Assamese numerals

- Tamil numerals

- Sinhala numerals

- Indian numbering system

- Khmer numerals

- Burmese numerals

- Thai numerals

- Lao numerals

- Javanese numerals

- Balinese numerals

References

- Notes

- ↑ List of numbers in various languages

- ↑ "zero - Origin and meaning of zero by Online Etymology Dictionary". http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=zero.

- ↑ Devanagari for TEX version 2.17, page 21

- ↑ "Alternate digits in Devanagari". Scriptsource.org. http://scriptsource.org/cms/scripts/page.php?item_id=entry_detail&uid=hvzj8v9yrg. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ↑ "Arabic numerals". http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/PrintHT/Arabic_numerals.html.

- ↑ Diller, Anthony (1996). New zeroes and Old Khmer. Australian National University. http://www.lc.mahidol.ac.th/Documents/Publication/MKS/25/diller1996new.pdf.

- ↑ The father of George Dantzig.

- ↑ Dantzig, Tobias (1954), Number / The Language of Science (4th ed.), The Free Press (Macmillan), pp. 29–30, ISBN 0-02-906990-4

- ↑ Geometry By Roger Fenn, Springer, 2001

- Sources

- Georges Ifrah, The Universal History of Numbers. John Wiley, 2000.

- Sanskrit Siddham (Bonji) Numbers

- Karl Menninger, Number Words and Number Symbols - A Cultural History of Numbers ISBN 0-486-27096-3 [1]

- David Eugene Smith and Louis Charles Karpinski, The Hindu-Arabic Numerals (1911) [2]