Medicine:Amaurosis fugax

| Amaurosis fugax | |

|---|---|

| |

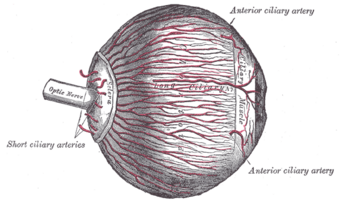

| The arteries of the choroid and iris. The greater part of the sclera has been removed. | |

| Symptoms | Temporary fleeting of vision in one or both eyes |

| Complications | Stroke[1][2] |

| Duration | Seconds to hours |

Amaurosis fugax (Greek: ἀμαύρωσις, amaurosis meaning 'darkening', 'dark', or 'obscure', Latin: fugax meaning 'fleeting') is a painless temporary loss of vision in one or both eyes.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The experience of amaurosis fugax is classically described as a temporary loss of vision in one or both eyes that appears as a "black curtain coming down vertically into the field of vision in one eye;" however, this altitudinal visual loss not the most common form. In one study, only 23.8 percent of patients with transient monocular vision loss experienced the classic "curtain" or "shade" descending over their vision.[4] Other descriptions of this experience include a monocular blindness, dimming, fogging, or blurring.[5] Total or sectorial vision loss typically lasts only a few seconds, but may last minutes or even hours. Duration depends on the cause of the vision loss. Obscured vision due to papilledema may last only seconds, while a severely atherosclerotic carotid artery may be associated with a duration of one to ten minutes.[6] Certainly, additional symptoms may be present with the amaurosis fugax, and those findings will depend on the cause of the transient monocular vision loss.[citation needed]

Cause

Prior to 1990, amaurosis fugax could, "clinically, be divided into four identifiable symptom complexes, each with its underlying pathoetiology: embolic, hypoperfusion, angiospasm, and unknown".[7] In 1990, the causes of amaurosis fugax were better refined by the Amaurosis Fugax Study Group, which has defined five distinct classes of transient monocular blindness based on their supposed cause: embolic, hemodynamic, ocular, neurologic, and idiopathic (or "no cause identified").[8] Concerning the pathology underlying these causes (except idiopathic), "some of the more frequent causes include atheromatous disease of the internal carotid or ophthalmic artery, vasospasm, optic neuropathies, giant cell arteritis, angle-closure glaucoma, increased intracranial pressure, orbital compressive disease, a steal phenomenon, and blood hyperviscosity or hypercoagulability."[9]

Embolic and hemodynamic origin

With respect to embolic and hemodynamic causes, this transient monocular visual loss ultimately occurs due to a temporary reduction in retinal artery, ophthalmic artery, or ciliary artery blood flow, leading to a decrease in retinal circulation which, in turn, causes retinal hypoxia.[10] While, most commonly, emboli causing amaurosis fugax are described as coming from an atherosclerotic carotid artery, any emboli arising from vasculature preceding the retinal artery, ophthalmic artery, or ciliary arteries may cause this transient monocular blindness.[citation needed]

- Atherosclerotic carotid artery: Amaurosis fugax may present as a type of transient ischemic attack (TIA), during which an embolus unilaterally obstructs the lumen of the retinal artery or ophthalmic artery, causing a decrease in blood flow to the ipsilateral retina. The most common source of these athero-emboli is an atherosclerotic carotid artery.[11]

However, a severely atherosclerotic carotid artery may also cause amaurosis fugax due to its stenosis of blood flow, leading to ischemia when the retina is exposed to bright light.[12] "Unilateral visual loss in bright light may indicate ipsilateral carotid artery occlusive disease and may reflect the inability of borderline circulation to sustain the increased retinal metabolic activity associated with exposure to bright light."[13] - Atherosclerotic ophthalmic artery: Will present similarly to an atherosclerotic internal carotid artery.[citation needed]

- Cardiac emboli: Thrombotic emboli arising from the heart may also cause luminal obstruction of the retinal, ophthalmic, and/or ciliary arteries, causing decreased blood flow to the ipsilateral retina; examples being those arising due to (1) atrial fibrillation, (2) valvular abnormalities including post-rheumatic valvular disease, mitral valve prolapse, and a bicuspid aortic valve, and (3) atrial myxomas.[citation needed]

- Temporary vasospasm leading to decreased blood flow can be a cause of amaurosis fugax.[14][15] Generally, these episodes are brief, lasting no longer than five minutes,[16] and have been associated with exercise.[10][17] These vasospastic episodes are not restricted to young and healthy individuals. "Observations suggest that a systemic hemodynamic challenge provoke[s] the release of vasospastic substance in the retinal vasculature of one eye."[16]

- Giant cell arteritis: Giant cell arteritis can result in granulomatous inflammation within the central retinal artery and posterior ciliary arteries of eye, resulting in partial or complete occlusion, leading to decreased blood flow manifesting as amaurosis fugax. Commonly, amaurosis fugax caused by giant cell arteritis may be associated with jaw claudication and headache. However, it is also not uncommon for these patients to have no other symptoms.[18] One comprehensive review found a two to nineteen percent incidence of amaurosis fugax among these patients.[19]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[20][21]

- Periarteritis nodosa[22]

- Eosinophilic vasculitis[23]

- Hyperviscosity syndrome[24]

- Polycythemia[25]

- Hypercoagulability[26]

- Thrombocytosis[29]

- Subclavian steal syndrome

- Malignant hypertension can cause ischemia of the optic nerve head leading to transient monocular visual loss.[32]

- Drug abuse-related intravascular emboli[8]

- Iatrogenic: Amaurosis fugax can present as a complication following carotid endarterectomy, carotid angiography, cardiac catheterization, and cardiac bypass.[29]

Ocular origin

Ocular causes include:

- Iritis[33]

- Keratitis[24]

- Blepharitis[24]

- Optic disc drusen[29]

- Posterior vitreous detachment[24]

- Closed-angle glaucoma[34]

- Transient elevation of intraocular pressure[8][33]

- Intraocular hemorrhage[8]

- Coloboma[29]

- Myopia[29]

- Orbital hemangioma[35]

- Orbital osteoma[36]

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca[29] testing

Neurologic origin

Neurological causes include:

- Optic neuritis[8]

- Compressive optic neuropathies[8][29]

- Papilledema: "The underlying mechanism for visual obscurations in all of these patients appear to be transient ischemia of the optic nerve head consequent to increased tissue pressure. Axonal swelling, intraneural masses, and increased influx of interstitial fluid may all contribute to increases in tissue pressure in the optic nerve head. The consequent reduction in perfusion pressure renders the small, low-pressure vessels that supply the optic nerve head vulnerable to compromise. Brief fluctuations in intracranial or systemic blood pressure may then result in transient loss of function in the eyes."[37] Generally, this transient visual loss is also associated with a headache and optic disk swelling.

- Multiple sclerosis can cause amaurosis fugax due to a unilateral conduction block, which is a result of demyelination and inflammation of the optic nerve, and "...possibly by defects in synaptic transmission and putative circulating blocking factors."[38]

- Migraine[39]

- Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension[40]

- Intracranial tumor[40]

- Psychogenic[24]

Diagnosis

Despite the temporary nature of the vision loss, those experiencing amaurosis fugax are usually advised to consult a physician immediately as it is a symptom that may herald serious vascular events, including transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.[1][2] Restated, "because of the brief interval between the transient event and a stroke or blindness from temporal arteritis, the workup for transient monocular blindness should be undertaken without delay." If the patient has no history of giant cell arteritis, the probability of vision preservation is high; however, the chance of a stroke reaches that for a hemispheric TIA. Therefore, investigation of cardiac disease is justified.[8]

A diagnostic evaluation should begin with the patient's history, followed by a physical exam, with particular importance being paid to the ophthalmic examination with regards to signs of ocular ischemia. When investigating amaurosis fugax, an ophthalmologic consultation is absolutely warranted if available. Several concomitant laboratory tests should also be ordered to investigate some of the more common, systemic causes listed above, including a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lipid panel, and blood glucose level. If a particular cause is suspected based on the history and physical, additional relevant labs should be ordered.[8]

If laboratory tests are abnormal, a systemic disease process is likely, and, if the ophthalmologic examination is abnormal, ocular disease is likely. However, in the event that both of these routes of investigation yield normal findings or an inadequate explanation, non-invasive duplex ultrasound studies are recommended to identify carotid artery disease. Most episodes of amaurosis fugax are the result of stenosis of the ipsilateral carotid artery.[41] With that being the case, researchers investigated how best to evaluate these episodes of vision loss, and concluded that for patients ranging from 36 to 74 years old, "...carotid artery duplex scanning should be performed...as this investigation is more likely to provide useful information than an extensive cardiac screening (ECG, Holter 24-hour monitoring, and precordial echocardiography)."[41] Additionally, concomitant head CT or MRI imaging is also recommended to investigate the presence of a "clinically silent cerebral embolism."[8]

If the results of the ultrasound and intracranial imaging are normal, "renewed diagnostic efforts may be made," during which fluorescein angiography is an appropriate consideration. However, carotid angiography may not be necessary in the presence of a normal ultrasound and CT.[42]

Treatment

Fleeting loss of vision does not in itself require any treatment, but it may indicate an underlying condition, sometimes serious, that must be treated. If the diagnostic workup reveals a systemic disease process, directed therapies to treat the underlying cause are required. If the amaurosis fugax is caused by an atherosclerotic lesion, use of aspirin as an anticoagulant is indicated, and a carotid endarterectomy considered based on the location and grade of the stenosis. Generally, if the carotid artery is still patent, the greater the stenosis, the greater the indication for endarterectomy. "Amaurosis fugax appears to be a particularly favorable indication for carotid endarterectomy. Left untreated, this event carries a high risk of stroke; after carotid endarterectomy, which has a low operative risk, there is a very low postoperative stroke rate."[43] However, the rate of subsequent stroke after amaurosis is significantly less than after a hemispheric TIA, therefore there remains debate as to the precise indications for which a carotid endarterectomy should be performed. If the full diagnostic workup is completely normal, patient observation is recommended.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: time window for prevention is very short". Neurology 64 (5): 817–20. March 2005. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000152985.32732.EE. PMID 15753415.

- ↑ "'Transient monocular blindness' versus 'amaurosis fugax'". Neurology 39 (12): 1622–4. December 1989. doi:10.1212/wnl.39.12.1622. PMID 2685658.

- ↑ "Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis". N Engl J Med 325 (7): 445–53. August 1991. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. PMID 1852179.

- ↑ "Transient monocular blindness". Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 18 (3): 299–305. August 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.1990.tb00624.x. PMID 2261177.

- ↑ "Clinical features of transient monocular blindness and the likelihood of atherosclerotic lesions of the internal carotid artery". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71 (2): 247–9. August 2001. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.2.247. PMID 11459904.

- ↑ "Amaurosis fugax. An overview". J Clin Neuroophthalmol 9 (3): 185–9. September 1989. PMID 2529279.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 "Current management of amaurosis fugax. The Amaurosis Fugax Study Group". Stroke 21 (2): 201–8. February 1990. doi:10.1161/01.str.21.2.201. PMID 2406992.

- ↑ "Cerebrovascular disease". Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 3 (5th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1998. pp. 3420–6. ISBN 0-683-30232-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Exercise-induced vasospastic amaurosis fugax". Arch. Ophthalmol. 120 (2): 220–2. February 2002. PMID 11831932. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/269443. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ↑ "Amaurosis Fugax and Stenosis of the Ophthalmic Artery". Vasc Endovascular Surg 35 (2): 141–2. 2001. doi:10.1177/153857440103500210. PMID 11668383.

- ↑ "Light-induced amaurosis fugax". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 131 (5): 674–6. May 2001. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00874-6. PMID 11336956.

- ↑ "Unilateral visual loss in bright light. An unusual symptom of carotid artery occlusive disease". Arch. Neurol. 36 (11): 675–6. November 1979. doi:10.1001/archneur.1979.00500470045007. PMID 508123.

- ↑ "Transient monocular blindness associated with hemiplegia". Arch. Ophthalmol. 47 (2): 167–203. 1952. doi:10.1001/archopht.1952.01700030174005. PMID 14894017.

- ↑ "Ocular complications of atherosclerosis: what do they mean?". Semin Neurol 6 (2): 185–93. June 1986. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041462. PMID 3332423.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Transient monocular blindness caused by vasospasm". N. Engl. J. Med. 325 (12): 870–3. September 1991. doi:10.1056/NEJM199109193251207. PMID 1875972.

- ↑ "Exercise-induced transient visual events in young healthy adults". J Clin Neuroophthalmol 9 (3): 178–80. 1989. PMID 2529277.

- ↑ "Occult giant cell arteritis: ocular manifestations". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 125 (4): 521–6. April 1998. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80193-7. PMID 9559738.

- ↑ "Temporal arteritis". Am. J. Med. 67 (5): 839–52. November 1979. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)90744-7. PMID 389046.

- ↑ "Transient visual symptoms in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome". Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 9 (1): 49–57. March 2001. doi:10.1076/ocii.9.1.49.3980. PMID 11262668.

- ↑ "Retinal arterial occlusive disease in systemic lupus erythematosus". Arch. Ophthalmol. 95 (9): 1580–5. September 1977. doi:10.1001/archopht.1977.04450090102008. PMID 901267.

- ↑ "Macula-sparing monocular blackouts. Clinical and pathologic investigations of intermittent choroidal vascular insufficiency in a case of periarteritis nodosa". Arch. Ophthalmol. 91 (5): 367–70. May 1974. doi:10.1001/archopht.1974.03900060379006. PMID 4150748.

- ↑ "Eosinophilic vasculitis leading to amaurosis fugax in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome". Arch. Intern. Med. 146 (10): 2059–60. 1986. doi:10.1001/archinte.146.10.2059. PMID 3767551.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 "Amaurosis Fugax-A Clinical Review". The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice 4 (2): 1–6. April 2006. http://ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/vol4num2/Bacigalupi.pdf.

- ↑ "Peripheral arterial occlusion and amaurosis fugax as the first manifestation of polycythemia vera. A case report". Blut 48 (3): 177–80. March 1984. doi:10.1007/BF00320341. PMID 6697006.

- ↑ "Transient monocular blindness and increased platelet aggregability treated with aspirin. A case report". Neurology 22 (3): 280–5. March 1972. doi:10.1212/wnl.22.3.280. PMID 5062262.

- ↑ "Protein C deficiency: a cause of amaurosis fugax?". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 50 (3): 361–2. March 1987. doi:10.1136/jnnp.50.3.361. PMID 3559620.

- ↑ "Amaurosis fugax associated with antiphospholipid antibodies". Annals of Neurology 25 (3): 228–32. March 1989. doi:10.1002/ana.410250304. PMID 2729913.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 "Amaurosis Fugax and Not So Fugax—Vascular Disorders of the Eye". Practical viewing of the optic disc. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. 2003. pp. 269–344. ISBN 0-7506-7289-7. http://intl.elsevierhealth.com/e-books/pdf/783.pdf. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ "Recurrent ischemic attacks in two young adults with lupus anticoagulant". Stroke 14 (3): 377–9. 1983. doi:10.1161/01.STR.14.3.377. PMID 6419415.

- ↑ "Thromboembolism in patients with the 'lupus'-type circulating anticoagulant". Arch. Intern. Med. 144 (3): 510–5. March 1984. doi:10.1001/archinte.144.3.510. PMID 6367679.

- ↑ "Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. V. Hypertensive optic neuropathy". Ophthalmology 93 (1): 74–87. January 1986. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33773-4. PMID 3951818.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Amaurosis fugax. A unselected material". Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 61 (4): 583–8. August 1983. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb04348.x. PMID 6637419.

- ↑ "Transient monocular visual loss from narrow-angle glaucoma". Arch. Neurol. 41 (9): 991–3. September 1984. doi:10.1001/archneur.1984.04050200097026. PMID 6477235.

- ↑ "Amaurosis fugax secondary to presumed cavernous hemangioma of the orbit". Ann Ophthalmol 13 (10): 1205–9. October 1981. PMID 7316347.

- ↑ "Osteoma: an unusual cause of amaurosis fugax". Mayo Clin. Proc. 54 (4): 258–60. April 1979. PMID 423606.

- ↑ "Transient visual obscurations with elevated optic discs". Annals of Neurology 16 (4): 489–94. October 1984. doi:10.1002/ana.410160410. PMID 6497356.

- ↑ "The pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis: the mechanisms underlying the production of symptoms and the natural history of the disease". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 354 (1390): 1649–73. October 1999. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0510. PMID 10603618.

- ↑ "Characteristics and prevalence of transient visual disturbances indicative of migraine visual aura". Cephalalgia 19 (5): 479–84. June 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019005479.x. PMID 10403062."Transient visual disturbances during migraine without aura attacks". Headache 42 (9): 930–3. October 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02216.x. PMID 12390623."Complicated migraine. A study of permanent neurological and visual defects caused by migraine". Lancet 2 (7265): 1072–5. November 1962. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(62)90782-1. PMID 14022628."Retinal migraine". Headache 10 (1): 9–13. April 1970. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1970.hed1001009.x. PMID 5444866."Migraine complicated by ischaemic papillopathy". Lancet 2 (7723): 521–3. September 1971. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(71)90440-5. PMID 4105666."Ocular migraine in a young man resulting in unilateral transient blindness and retinal edema". Pediatr Ophthalmol. 8: 173–6. 1971."Ocular migraine in a patient with cluster headaches". Headache 20 (5): 253–7. September 1980. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1980.hed2005253.x. PMID 7451120.Corbett JJ. (1983). "Neuro-ophthalmologic complications of migraine and cluster headaches". Neurol. Clin. 1 (4): 973–95. doi:10.1016/S0733-8619(18)31134-4. PMID 6390159.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Hedges TR (1984). "The terminology of transient visual loss due to vascular insufficiency". Stroke 15 (5): 907–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.15.5.907. PMID 6474546.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "The source of embolism in amaurosis fugax and retinal artery occlusion". Int Ophthalmol 18 (2): 83–6. 1994. doi:10.1007/BF00919244. PMID 7814205. http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/1/1/136.pdf.

- ↑ "Carotid endarterectomy for amaurosis fugax without angiography". Am. J. Surg. 152 (2): 172–4. August 1986. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(86)90236-9. PMID 3526933.

- ↑ "Late results after carotid endarterectomy for amaurosis fugax". J. Vasc. Surg. 6 (4): 333–40. October 1987. doi:10.1016/0741-5214(87)90003-6. PMID 3656582.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|