Multiple kernel learning

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

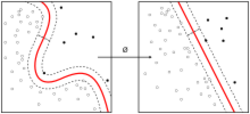

Multiple kernel learning refers to a set of machine learning methods that use a predefined set of kernels and learn an optimal linear or non-linear combination of kernels as part of the algorithm. Reasons to use multiple kernel learning include a) the ability to select for an optimal kernel and parameters from a larger set of kernels, reducing bias due to kernel selection while allowing for more automated machine learning methods, and b) combining data from different sources (e.g. sound and images from a video) that have different notions of similarity and thus require different kernels. Instead of creating a new kernel, multiple kernel algorithms can be used to combine kernels already established for each individual data source.

Multiple kernel learning approaches have been used in many applications, such as event recognition in video,[1] object recognition in images,[2] and biomedical data fusion.[3]

Algorithms

Multiple kernel learning algorithms have been developed for supervised, semi-supervised, as well as unsupervised learning. Most work has been done on the supervised learning case with linear combinations of kernels, however, many algorithms have been developed. The basic idea behind multiple kernel learning algorithms is to add an extra parameter to the minimization problem of the learning algorithm. As an example, consider the case of supervised learning of a linear combination of a set of kernels . We introduce a new kernel , where is a vector of coefficients for each kernel. Because the kernels are additive (due to properties of reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces), this new function is still a kernel. For a set of data with labels , the minimization problem can then be written as

where is an error function and is a regularization term. is typically the square loss function (Tikhonov regularization) or the hinge loss function (for SVM algorithms), and is usually an norm or some combination of the norms (i.e. elastic net regularization). This optimization problem can then be solved by standard optimization methods. Adaptations of existing techniques such as the Sequential Minimal Optimization have also been developed for multiple kernel SVM-based methods.[4]

Supervised learning

For supervised learning, there are many other algorithms that use different methods to learn the form of the kernel. The following categorization has been proposed by Gonen and Alpaydın (2011)[5]

Fixed rules approaches

Fixed rules approaches such as the linear combination algorithm described above use rules to set the combination of the kernels. These do not require parameterization and use rules like summation and multiplication to combine the kernels. The weighting is learned in the algorithm. Other examples of fixed rules include pairwise kernels, which are of the form

- .

These pairwise approaches have been used in predicting protein-protein interactions.[6]

Heuristic approaches

These algorithms use a combination function that is parameterized. The parameters are generally defined for each individual kernel based on single-kernel performance or some computation from the kernel matrix. Examples of these include the kernel from Tenabe et al. (2008).[7] Letting be the accuracy obtained using only , and letting be a threshold less than the minimum of the single-kernel accuracies, we can define

Other approaches use a definition of kernel similarity, such as

Using this measure, Qui and Lane (2009)[8] used the following heuristic to define

Optimization approaches

These approaches solve an optimization problem to determine parameters for the kernel combination function. This has been done with similarity measures and structural risk minimization approaches. For similarity measures such as the one defined above, the problem can be formulated as follows:[9]

where is the kernel of the training set.

Structural risk minimization approaches that have been used include linear approaches, such as that used by Lanckriet et al. (2002).[10] We can define the implausibility of a kernel to be the value of the objective function after solving a canonical SVM problem. We can then solve the following minimization problem:

where is a positive constant. Many other variations exist on the same idea, with different methods of refining and solving the problem, e.g. with nonnegative weights for individual kernels and using non-linear combinations of kernels.

Bayesian approaches

Bayesian approaches put priors on the kernel parameters and learn the parameter values from the priors and the base algorithm. For example, the decision function can be written as

can be modeled with a Dirichlet prior and can be modeled with a zero-mean Gaussian and an inverse gamma variance prior. This model is then optimized using a customized multinomial probit approach with a Gibbs sampler.

[11] These methods have been used successfully in applications such as protein fold recognition and protein homology problems [12][13]

Boosting approaches

Boosting approaches add new kernels iteratively until some stopping criteria that is a function of performance is reached. An example of this is the MARK model developed by Bennett et al. (2002) [14]

The parameters and are learned by gradient descent on a coordinate basis. In this way, each iteration of the descent algorithm identifies the best kernel column to choose at each particular iteration and adds that to the combined kernel. The model is then rerun to generate the optimal weights and .

Semisupervised learning

Semisupervised learning approaches to multiple kernel learning are similar to other extensions of supervised learning approaches. An inductive procedure has been developed that uses a log-likelihood empirical loss and group LASSO regularization with conditional expectation consensus on unlabeled data for image categorization. We can define the problem as follows. Let be the labeled data, and let be the set of unlabeled data. Then, we can write the decision function as follows.

The problem can be written as

where is the loss function (weighted negative log-likelihood in this case), is the regularization parameter (Group LASSO in this case), and is the conditional expectation consensus (CEC) penalty on unlabeled data. The CEC penalty is defined as follows. Let the marginal kernel density for all the data be

where (the kernel distance between the labeled data and all of the labeled and unlabeled data) and is a non-negative random vector with a 2-norm of 1. The value of is the number of times each kernel is projected. Expectation regularization is then performed on the MKD, resulting in a reference expectation and model expectation . Then, we define

where is the Kullback-Leibler divergence. The combined minimization problem is optimized using a modified block gradient descent algorithm. For more information, see Wang et al.[15]

Unsupervised learning

Unsupervised multiple kernel learning algorithms have also been proposed by Zhuang et al. The problem is defined as follows. Let be a set of unlabeled data. The kernel definition is the linear combined kernel . In this problem, the data needs to be "clustered" into groups based on the kernel distances. Let be a group or cluster of which is a member. We define the loss function as . Furthermore, we minimize the distortion by minimizing . Finally, we add a regularization term to avoid overfitting. Combining these terms, we can write the minimization problem as follows.

where . One formulation of this is defined as follows. Let be a matrix such that means that and are neighbors. Then, . Note that these groups must be learned as well. Zhuang et al. solve this problem by an alternating minimization method for and the groups . For more information, see Zhuang et al.[16]

Libraries

Available MKL libraries include

- SPG-GMKL: A scalable C++ MKL SVM library that can handle a million kernels.[17]

- GMKL: Generalized Multiple Kernel Learning code in MATLAB, does and regularization for supervised learning.[18]

- (Another) GMKL: A different MATLAB MKL code that can also perform elastic net regularization[19]

- SMO-MKL: C++ source code for a Sequential Minimal Optimization MKL algorithm. Does -n orm regularization.[20]

- SimpleMKL: A MATLAB code based on the SimpleMKL algorithm for MKL SVM.[21]

- MKLPy: A Python framework for MKL and kernel machines scikit-compliant with different algorithms, e.g. EasyMKL[22] and others.

References

- ↑ Lin Chen, Lixin Duan, and Dong Xu, "Event Recognition in Videos by Learning From Heterogeneous Web Sources," in IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2013, pp. 2666-2673

- ↑ Serhat S. Bucak, Rong Jin, and Anil K. Jain, Multiple Kernel Learning for Visual Object Recognition: A Review. T-PAMI, 2013.

- ↑ Yu et al. L2-norm multiple kernel learning and its application to biomedical data fusion. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11:309

- ↑ Francis R. Bach, Gert R. G. Lanckriet, and Michael I. Jordan. 2004. Multiple kernel learning, conic duality, and the SMO algorithm. In Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning (ICML '04). ACM, New York, NY, USA

- ↑ Mehmet Gönen, Ethem Alpaydın. Multiple Kernel Learning Algorithms Jour. Mach. Learn. Res. 12(Jul):2211−2268, 2011

- ↑ Ben-Hur, A. and Noble W.S. Kernel methods for predicting protein-protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jun;21 Suppl 1:i38-46.

- ↑ Hiroaki Tanabe, Tu Bao Ho, Canh Hao Nguyen, and Saori Kawasaki. Simple but effective methods for combining kernels in computational biology. In Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Research, Innovation and Vision for the Future, 2008.

- ↑ Shibin Qiu and Terran Lane. A framework for multiple kernel support vector regression and its applications to siRNA efficacy prediction. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, 6(2):190–199, 2009

- ↑ Gert R. G. Lanckriet, Nello Cristianini, Peter Bartlett, Laurent El Ghaoui, and Michael I. Jordan. Learning the kernel matrix with semidefinite programming. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 5:27–72, 2004a

- ↑ Gert R. G. Lanckriet, Nello Cristianini, Peter Bartlett, Laurent El Ghaoui, and Michael I. Jordan. Learning the kernel matrix with semidefinite programming. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2002

- ↑ Mark Girolami and Simon Rogers. Hierarchic Bayesian models for kernel learning. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning, 2005

- ↑ Theodoros Damoulas and Mark A. Girolami. Combining feature spaces for classification. Pattern Recognition, 42(11):2671–2683, 2009

- ↑ Theodoros Damoulas and Mark A. Girolami. Probabilistic multi-class multi-kernel learning: On protein fold recognition and remote homology detection. Bioinformatics, 24(10):1264–1270, 2008

- ↑ Kristin P. Bennett, Michinari Momma, and Mark J. Embrechts. MARK: A boosting algorithm for heterogeneous kernel models. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2002

- ↑ Wang, Shuhui et al. S3MKL: Scalable Semi-Supervised Multiple Kernel Learning for Real-World Image Applications. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA, VOL. 14, NO. 4, AUGUST 2012

- ↑ J. Zhuang, J. Wang, S.C.H. Hoi & X. Lan. Unsupervised Multiple Kernel Learning. Jour. Mach. Learn. Res. 20:129–144, 2011

- ↑ Ashesh Jain, S. V. N. Vishwanathan and Manik Varma. SPG-GMKL: Generalized multiple kernel learning with a million kernels. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Beijing, China, August 2012

- ↑ M. Varma and B. R. Babu. More generality in efficient multiple kernel learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, Canada, June 2009

- ↑ Yang, H., Xu, Z., Ye, J., King, I., & Lyu, M. R. (2011). Efficient Sparse Generalized Multiple Kernel Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 22(3), 433-446

- ↑ S. V. N. Vishwanathan, Z. Sun, N. Theera-Ampornpunt and M. Varma. Multiple kernel learning and the SMO algorithm. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, B. C., Canada, December 2010.

- ↑ Alain Rakotomamonjy, Francis Bach, Stephane Canu, Yves Grandvalet. SimpleMKL. Journal of Machine Learning Research, Microtome Publishing, 2008, 9, pp.2491-2521.

- ↑ Fabio Aiolli, Michele Donini. EasyMKL: a scalable multiple kernel learning algorithm. Neurocomputing, 169, pp.215-224.

|