Orthogonal functions

In mathematics, orthogonal functions belong to a function space that is a vector space equipped with a bilinear form. When the function space has an interval as the domain, the bilinear form may be the integral of the product of functions over the interval:

The functions and are orthogonal when this integral is zero, i.e. whenever . As with a basis of vectors in a finite-dimensional space, orthogonal functions can form an infinite basis for a function space. Conceptually, the above integral is the equivalent of a vector dot product; two vectors are mutually independent (orthogonal) if their dot-product is zero.

Suppose is a sequence of orthogonal functions of nonzero L2-norms . It follows that the sequence is of functions of L2-norm one, forming an orthonormal sequence. To have a defined L2-norm, the integral must be bounded, which restricts the functions to being square-integrable.

Trigonometric functions

Several sets of orthogonal functions have become standard bases for approximating functions. For example, the sine functions sin nx and sin mx are orthogonal on the interval when and n and m are positive integers. For then

and the integral of the product of the two sine functions vanishes.[1] Together with cosine functions, these orthogonal functions may be assembled into a trigonometric polynomial to approximate a given function on the interval with its Fourier series.

Polynomials

If one begins with the monomial sequence on the interval and applies the Gram–Schmidt process, then one obtains the Legendre polynomials. Another collection of orthogonal polynomials are the associated Legendre polynomials.

The study of orthogonal polynomials involves weight functions that are inserted in the bilinear form:

For Laguerre polynomials on the weight function is .

Both physicists and probability theorists use Hermite polynomials on , where the weight function is or .

Chebyshev polynomials are defined on and use weights or .

Zernike polynomials are defined on the unit disk and have orthogonality of both radial and angular parts.

Binary-valued functions

Walsh functions and Haar wavelets are examples of orthogonal functions with discrete ranges.

Rational functions

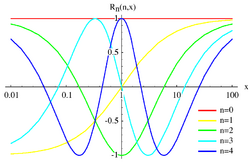

Legendre and Chebyshev polynomials provide orthogonal families for the interval [−1, 1] while occasionally orthogonal families are required on [0, ∞). In this case it is convenient to apply the Cayley transform first, to bring the argument into [−1, 1]. This procedure results in families of rational orthogonal functions called Legendre rational functions and Chebyshev rational functions.

In differential equations

Solutions of linear differential equations with boundary conditions can often be written as a weighted sum of orthogonal solution functions (a.k.a. eigenfunctions), leading to generalized Fourier series.

See also

- Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- Hilbert space

- Karhunen–Loève theorem

- Lauricella's theorem

- Wannier function

References

- ↑ Antoni Zygmund (1935) Trigonometrical Series, page 6, Mathematical Seminar, University of Warsaw

- George B. Arfken & Hans J. Weber (2005) Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 6th edition, chapter 10: Sturm-Liouville Theory — Orthogonal Functions, Academic Press.

- Price, Justin J. (1975). "Topics in orthogonal functions". American Mathematical Monthly 82: 594–609. doi:10.2307/2319690. http://www.maa.org/programs/maa-awards/writing-awards/topics-in-orthogonal-functions. Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- Giovanni Sansone (translated by Ainsley H. Diamond) (1959) Orthogonal Functions, Interscience Publishers.

External links

- Orthogonal Functions, on MathWorld.

|