Social:Chamalal language

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Chamalal | |

|---|---|

| чамалалдуб мичӏчӏ çamalaldub miçʿçʿ | |

| Pronunciation | [t͡ʃʼamalaldub mit͡sʼ] |

| Native to | North Caucasus |

| Region | Southwestern Dagestan[1] |

| Ethnicity | Chamalal people |

Native speakers | 5,171 (2020)[2] |

Northeast Caucasian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | cji |

| Glottolog | cham1309[3] |

Chamalal | |

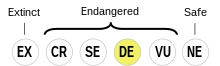

Chamalal is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

Chamalal (also called Camalal or Chamalin) is an Andic language of the Northeast Caucasian language family spoken in southwestern Dagestan, Russia by approximately 5,100 ethnic Chamalals. It has three quite distinct dialects, Gadyri, Gakvari, and Gigatl.[4]

Classification

Chamalal has three distinct dialects: Gadyri (Gachitl-Kvankhi), Gakvari (Agvali-Richaganik-Tsumada-Urukh), and Gigatl (Hihatl). There are also two more dialects: Kwenkhi, Tsumada.

Derived languages

Gigatl (Hihatl) and Chamalal proper (with Gadyri, Gakvari, Tsumada and Kwenkhi dialects) are considered to be sublanguages.

Geographic distribution

The approximately 500 ethnic speakers live in eight villages in the Tsumadinsky District on the left bank of the Andi-Koisu river in the Dagestan Republic and in the Chechnya Republic. The speakers are mostly Muslim, primarily following Sunni Islam since the 8th or 9th century.

Official status

There are no countries with Chamalal as an official language.

History

Chamalal is spoken in southwestern Dagestan, Russia by indigenous Chamalals since the 8th or 9th century. The ethnic population is approximately 5,000, with around 5,100 speakers.[2] The language has a 6b (threatened) status.[5]

Writing system

Chamalal is an unwritten language. Avar and Russian are used in school, and Avar is also used for literary purposes.

References

- ↑ Ethnologue language map of European Russia, with Chamalal in the inset with reference number 10

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 7. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОСТЕЙ ПО РОДНОМУ ЯЗЫКУ

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Chamalal". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/cham1309.

- ↑ Lewis, M. Paul, ed (2015). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (18th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. https://www.ethnologue.com/18/.

- ↑ "Чамалинский язык | Малые языки России". https://minlang.iling-ran.ru/lang/chamalinskiy-yazyk.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Stephen (2005). "Review: The Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus, Vols. 1-4". Language 81 (4): 993–996. doi:10.1353/lan.2005.0161.

- "Back Matter". Historische Sprachforschung / Historical Linguistics 109 (2). 1996.

- Blažek, Václav (2002). "The 'beech'-argument — State-of-the-Art". Historische Sprachforschung / Historical Linguistics 115 (2): 190–217.

- Friedman, Victor (2005). "Review:The Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus, Volume 3: The North East Caucasian Languages, Part 1". The Slavic and East European Journal 49 (3): 537–539. doi:10.2307/20058337.

- Greppin, John A. C. (1996). "New Data on the Hurro-Urartian Substratum in Armenian". Historische Sprachforschung / Historical Linguistics 109 (1): 40–44.

- Harris, Alice C. (2009). "Exuberant Exponence in Batsbi". Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 27 (2): 267–303. doi:10.1007/s11049-009-9070-8.

- Haspelmath, Martin (1996). "Review:The Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus, Vol. 4: North East Caucasian Languages, Part 2". Language 72 (1): 126–129. doi:10.2307/416797.

- Kolga, M.; Tõnurist, I.; Vaba, L.; Viikberg, J. (1993). The Red book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire.

- Magomedova, P. T. (2004). "Chamalal". The Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus. 3: The North East Caucasian Languages, Part 1. pp. 3–65.

- Schulze, Wolfgang (2005). "Grammars for East Caucasian". Anthropological Linguistics 47 (3): 321–352.

- Szczśniak, Andrew L. (1963). "A Brief Index of Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Asiatic Russia". Anthropological Linguistics 5 (6): 1–29.

- Tuite, Kevin; Schulze, Wolfgang (1998). "A Case of Taboo-Motivated Lexical Replacement in the Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus". Anthropological Linguistics 40 (3): 363–383.

- Voegelin, C. F.; Voegelin, F. M. (1966). "Index of Languages of the World". Anthropological Linguistics 8 (6): i-xiv, 1-222.

Further reading

- "The Chamalals". The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. 1993. https://redbook.verbix.com/chamalals.shtml.

|