Software:Virtua Racing

| Virtua Racing | |

|---|---|

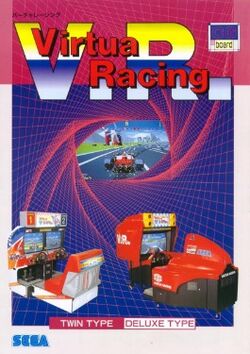

Arcade flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Sega AM2 |

| Publisher(s) | Sega Time Warner (Saturn) |

| Director(s) | Yu Suzuki |

| Designer(s) | Toshihiro Nagoshi |

| Programmer(s) | Yu Suzuki |

| Composer(s) | Takenobu Mitsuyoshi |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Mega Drive/Genesis, 32X, Sega Saturn |

| Release | August 1992

|

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

| Arcade system | Sega Model 1 |

Virtua Racing (V.R.) is a 1992 Formula One racing video game developed by Sega AM2 and published by Sega for arcades. It was initially a proof-of-concept application for exercising the "Model 1", a new 3D graphics platform then under development. The results were so encouraging that Virtua Racing was fully developed into a standalone arcade title.

The original arcade game has three circuits, designated into difficulties. Beginner is Big Forest, intermediate is Bay Bridge and expert is Acropolis. Each level has its own special feature, for example the amusement park in "Big Forest", or the "Bay Bridge" itself, or the tight hairpin of "Acropolis". When selecting a car, the player can choose different transmission types.[2] VR introduced the "V.R. View System" by allowing the player to choose one of four views to play the game. This feature was then used in most other Sega arcade racing games (and is mentioned as a feature in the attract mode of games such as Daytona USA).

Virtua Racing was among the highest-grossing arcade games of 1992 in Japan and North America, 1993 in Europe, Australia and worldwide. It successfully received the award for Most Innovative New Technology from the Amusement & Music Operators Association (AMOA). Virtua Racing is regarded as one of the most influential video games of all time, for laying the foundations for subsequent 3D racing games and for popularizing 3D polygon graphics among a wider audience. It was later ported to home consoles, starting with the Mega Drive/Genesis in 1994.

Arcade cabinet versions

Twin

V.R. was released in a "twin" cabinet – the standard and most common version, which is effectively 2 complete machines built into a single cabinet. The Twin cabinets for the U.S. were manufactured by contract at Grand Products, Inc. in Illinois for Sega and were built using Wells-Gardner 25" monitors. The Twin cabinet that was sold in the rest of the world was built by Sega in Japan and used 29" Nanao monitors.

Also available was an upright (UR), which was a single-player cabinet using the same force-feedback steering as the twin. The cabinet cost between about $18,000 (equivalent to $40,000 in 2024)[3] and £12,000 or $Undefined year "1,992",000 (equivalent to $Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN, check parameters for non-numeric data: |value=Undefined year "1,992"000 (parameter 2). in 2024).[4]

DX

There was also a Deluxe version, known as the V.R. DX cabinet type, which is also a single-player machine and has a 16:9 aspect-ratio Hantarex monitor (the first use of a widescreen aspect ratio monitor in an arcade game), and 6 airbags (3 on each side) built into the seat that will inflate and "nudge" the player when cornering, and one more airbag on the player's back that inflates under braking. The seat is also adjustable via "forward" and "back" buttons using air pressure. V.R. DX's force-feedback steering also uses two pneumatic cylinders to rotate the steering wheel, which differ from the electric motor-and-clutch system that the upright and twin versions use (which have no inbuilt air system), so the steering feel is quite different.

The Deluxe version was manufactured in Sega's Japanese factories for worldwide markets, while the Twin version in the US was manufactured domestically by Grand Products. The Deluxe version was priced at $2 per play and the Twin version at $0.75 per play. While Sega had previously charged higher for the R360 cabinet, this was the first time that a mass-production arcade game cost $2 per play.[5] In 1992, the cabinet cost £20,000 or $Undefined year "1,992",000 (equivalent to $Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN, check parameters for non-numeric data: |value=Undefined year "1,992"000 (parameter 2). in 2024) to purchase.[6]

Virtua Formula

Virtua Formula was released in 1993. It was unveiled at the opening of Sega's second arcade amusement park Joypolis, where a whole room with 32 machines was dedicated to the game. Virtua Formula was effectively a "super DX" version of V.R. and the player sat in a full-motion hydraulically actuated Formula One car 'replica' in front of a 50-inch screen. Most of these units were converted into Sega's second-generation Indy car simulator, Indy 500, and are commonly found at larger Sega Gameworks locations in the U.S.

All versions of Virtua Racing are linkable up to 8-players; meaning 4 twin units or 8 DX, UR, or Virtua Formula cabinets can be linked together using fiber-optic cables. In addition to this, there was an optional display known as the Live Monitor that would sit atop the twin cabinets and replay action shots of what was occurring with actual players in a "virtual sportscast" by a virtual commentator, "Virt McPolygon". A four-player Virtua Formula cabinet setup cost around £250,000 or $Undefined year "1,994",000 (equivalent to $Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN, check parameters for non-numeric data: |value=Undefined year "1,994"000 (parameter 2). in 2024) in 1994.[7]

Development

Virtua Racing was developed alongside the Sega Model 1 arcade system, originally called the "CG Board" system prior to completion. The game was directed by Yu Suzuki and designed by Toshihiro Nagoshi.[8]

The origins of Virtua Racing, along with the Model 1, date back to the development of the Mega Drive/Genesis console prior to its launch in 1988. The console was a major leap forward for home video game systems, allowing them to come closer to arcade quality. For Sega's arcade games to remain profitable, they needed to maintain a wide gap between arcade and home video games. At a meeting held during the console's development, Sega decided to begin development on an arcade system capable of producing 3D polygon graphics. This led to the development of the Sega Model 1, along with Virtua Racing, by the early 1990s. They had arcade competitors (Namco and Atari Games) who predated Sega in the use of 3D polygon graphics, displaying up to 2,000 polygons per frame, so Sega increased their Model 1 system's capabilities significantly beyond that to 6,500 polygons per frame.[5]

In 1989, Sega of America's Tom Petit mentioned that Sega was "hiring 400 new engineers to research and develop new technology" and that they "have innovative, revolutionary graphics display systems to come" which would make even Super Monaco GP (their latest arcade racer at the time) "seem like the yesterday of technology."[9] The Sega Model 1 system was developed internally at Sega between 1990 and 1991.[10][11] In 1991, Petit stated that, "next year, you will see a new trend of technology that will be instrumental in providing new vitality for our industry" and that it could "have as much impact on the business as" Hang-On "did to influence our last growth market" back in 1985.[12]

Home console versions

Sega Mega Drive/Genesis

Due to the complexity of the Model 1 board, a home console version seemed unlikely, until 1994 when a cartridge design incorporating the Sega Virtua Processor (SVP) on an extra chip was created to enable a version on the Genesis/Mega Drive. This chip was extremely expensive to manufacture, leading Sega to price the Genesis version of Virtua Racing unusually high: US$100 in the United States[13] and £70 in the United Kingdom.

The game renders 9,000 polygons per second with the SVP chip, significantly higher than what the standard Genesis/Mega Drive hardware is capable of.[14] It also outperformed Nintendo's rival SuperFX chip for the Super NES.[4] The game was incompatible with Majesco Entertainment's re-released Genesis 3 from 1998, and would not work on any Genesis equipped with a Sega 32X.

32X

The Sega 32X version, also known as Virtua Racing Deluxe, was released as launch title for North America in 1994, and then a year later in PAL regions. It was developed by Sega AM2, and published by Sega under the Sega Sports label. It performed a bit more closely to the original arcade version and included two extra cars ("Stock" and "Prototype") as well as two new tracks ("Highland" and "Sand Park").

Sega Saturn

The Sega Saturn version, titled Time Warner Interactive's VR Virtua Racing, and previously known by the working title Virtua Racing Saturn, was released in 1995 and developed and published by Time Warner Interactive. As the developers lacked the original source code, they had to create this version based on observation of the arcade game.[15][16] The Saturn release has the game soundtrack as standard Red Book audio, which can be listened to in any CD player. The Saturn version also includes seven new courses and four new cars, as well as a secret "F-200 Super Car" unlockable via a cheat code, or by placing first in every race with every car. Unlike other versions, it features Grand Prix mode, where players drive a series of cars and the tracks to earn points.[17][18][19]

PlayStation 2

A remake, called Virtua Racing: FlatOut, was released for the PlayStation 2 under the Sega Ages 2500 label. It was released in Japan in 2004 and in North America and Europe in 2005 as part of the Sega Classics Collection titled simply Virtua Racing. It includes three new courses and four new cars.

Nintendo Switch

As part of the Sega Ages series, a port of Virtua Racing for the Nintendo Switch was released digitally in Japan on April 24, 2019, and elsewhere on June 27. Developed by M2,[20] it is a port of the original arcade version with the frame rate increased to 60fps and presented in the 16:9 aspect ratio.[20] Also new to this port is the ability to play online with up to 2 players and offline with up to 8 players on a single system.[20][21] The game also features online leaderboards with downloadable replays for the top 50 players on each track, an additional easier steering option and a Grand Prix mode that increases the number of laps to 20. Virt McPolygon also cameos in the game upon replaying a Grand Prix race.[22]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arcade

The arcade game was a major worldwide commercial success upon release, surpassing Sega's expectations and with high demand exceeding production output. The Deluxe and Twin cabinets were both selling very well, with the expensive Deluxe version selling about a fifth as many units as the less expensive Twin version during 1992.[5] In Japan, Game Machine listed it as the most successful upright/cockpit arcade cabinet of October 1992.[50] In the United States, it debuted at the top of the RePlay arcade earnings chart for deluxe cabinets in October 1992.[51] It remained at the top for the rest of the year[52][53] and much of the following year, from February 1993[54][55][56] to July 1993,[57][58][59] until it was dethroned by Sega AM1's Stadium Cross (with Virtua Racing at number two) in August 1993.[60] Virtua Racing remained at number two in October 1993, below Suzuka 8 Hours.[61] Virtua Racing was America's third top-grossing arcade game during Summer 1993.[62] The game was also a major commercial success in Europe.[5]

Virtua Racing was one of the top ten highest-grossing arcade games of 1992 in Japan[63] and the United States.[64] The following year, it was the highest-grossing dedicated arcade game of 1993 in Japan,[65] and one of America's top five highest-grossing arcade games of 1993.[66][67]

The arcade game was well received by critics upon release. Electronic Gaming Monthly called it a "racing masterpiece" and said its "lifelike racing sensations are extremely impressive and exciting". They called it "one of the most realistic racing games ever" and concluded that it leaves "all other racing games eating its technological dust".[2] Computer and Video Games reviewed Virtua Formula in early 1994, stating that it is "one of the most exciting" arcade driving games and praising the "hydraulic control" of the cabinet. They concluded that, while its graphics are not as "drop-dead stunning" as the more recent Ridge Racer, Virtua Racing still has a greater "heart-pumping sense of speed".[7] Brazilian magazine Ação Games gave the game 4/4 on all four categories, and called it the most complex racing game on Earth.[68]

At Japan's 1992 Gamest Awards (ja), it was nominated for Best Action, Best Direction, and Best Graphics, but lost to Street Fighter II′: Champion Edition, Art of Fighting, and Xexex, respectively.[42] At North America's 1993 AMOA Awards, held by the Amusement & Music Operators Association (AMOA), Virtua Racing won the award for Most Innovative New Technology.[43]

Ports

GamePro named the Genesis/Mega Drive version the best Genesis game shown at the 1994 Consumer Electronics Show, commenting: "While obviously a great deal of graphic clarity, detail, and color was lost, the game play is stunningly faithful to the coin-op. ... this is the best version [of Virtua Racing] you'll see until Sega's mystery 32-bit home system leaves orbit".[44] In their later review, they complimented the game on its inclusion of all the elements of the arcade version aside from the support for up to eight players, and remarked that though the graphics are not as good as the arcade version, they feature faster-moving polygons than any other cartridge game. They criticized the audio and low longevity but nonetheless concluded "VR is the best 16-bit racer yet".[69]The four reviewers in Electronic Gaming Monthly criticized the audio but held that the game, though not as good as the arcade version, was the best racer yet seen on cartridge-based systems.[26] Famitsu magazine scored the Mega Drive version of the game 33 out of 40, calling it a "groundbreaking" port;[28] Diehard GameFan stated that "the speed, graphic intensity and addictive gameplay that made the arcade game a major hit are all included in this awe inspiring release".[30] Mega placed the game at number 4 in their Top Mega Drive Games of All Time.[70]

GamePro gave the 32X version a highly positive review, stating that it successfully addressed the Genesis version's longevity problem with its new cars and new tracks. They also praised the improved graphics, details, and controls, and the retention of on-the-fly view switching even in two-player split-screen mode.[71] Next Generation reviewed the 32X version of the game, Virtua Racing Deluxe, and stated that "VR Deluxe is a near-perfect conversion of a game that's still fun to play".[34]

The two sports reviewers of Electronic Gaming Monthly gave the Saturn version scores of 8 and 7 out of 10, with the first reviewer praising the added content and overall improvement over the previous home ports, and the second reviewer saying that the game is enjoyable but doesn't fully use the graphical capabilities of the Saturn.[27] GamePro similarly remarked: "This version not only looks better than both the Genesis and 32X versions, it also has a ton more options". They remarked that the graphics are not as good as Daytona USA, but that the game has better music and is more fun to play.[72] A reviewer for Next Generation felt that Virtua Racing was antiquated by this time, particularly with the imminent release of Sega Rally Championship on the Saturn. However, he acknowledged that the game had enough historical impact to draw its share of loyalists, and said the Saturn version "is not only arcade-perfect, it also contains crucial features not present in the original".[35] Rich Leadbetter of Sega Saturn Magazine praised the additional tracks and cars as giving the game more depth than an arcade racer, but countered that what most gamers wanted was a straight conversion of the coin-op Virtua Racing, not a home-oriented remake. He concluded that the Saturn version is good on its own terms, but completely overshadowed by the Saturn conversion of Sega Rally Championship, which was to be released just a few weeks after.[40] Maximum made the same comments but were more vehement in their criticism of the fact that the Saturn version is not a straight conversion of the arcade game.[37]

Legacy

In 1994, it appeared at 4th place on Mega's list of Top Mega Drive Games of All Time.[47] In 1995, Flux magazine rated the arcade version 36th in its "Top 100 Video Games."[73] In 1996, the arcade, 32X, and Saturn versions (but not the Genesis version) appeared at 11th place on Next Generation's list of Top 100 Games of All Time. They noted that their ranking it higher than any other racing game on the list (including Sega Rally Championship and Daytona USA) was deliberate, since Virtua Racing "drives better".[48] In 1996, GamesMaster ranked the arcade version 32nd on their "Top 100 Games of All Time."[74] In 1998, Saturn Power listed the game 92nd in its Top 100 Sega Saturn Games.[75] the felt that Virtua Racing is "not as arcade perfect as it should’ve been."[76]

Impact

In January 1993, RePlay magazine reported that "Sega credits Virtua Racing with a huge impact on the rest of the coin-op market" and "believes its new hi-tech driver has single-handedly lifted the simulator niche" into "a growth market." While acknowledging they had arcade competitors who had introduced 3D polygon graphics before them, Sega of America's Tom Petit and Ken Anderson said in December 1992 that Sega approached 3D polygons in their own way with Virtua Racing, which had much more advanced technology, was more successful than earlier attempts, and pushed Sega to the forefront of 3D polygon technology. Petit and Anderson noted the game was drawing large casual audiences, stating "it's bringing new people into locations" who "never played before" or "ordinarily wouldn't enter an amusement environment" but "word of mouth, the new technology and so on are bringing in new players" both young and old, male and female.[5]

Though its use of 3D polygon graphics was predated by arcade rivals Namco (Winning Run in 1988) and Atari Games (Hard Drivin' in 1989), Virtua Racing had vastly improved visuals in terms of polygon count, frame rate, and overall scene complexity, and displayed multiple camera angles and 3D human non-player characters, which all contributed to a greater sense of immersion. Virtua Racing is regarded as one of the most influential video games of all time, for laying the foundations for subsequent 3D racing games and for popularizing 3D polygonal graphics among a wider audience.[77][78]

In 2015, it appeared at 3rd place on IGN's list of The Top 10 Most Influential Racing Games Ever, behind Pole Position and Gran Turismo. According to Luke Reilly, while Winning Run was the first racing game with 3D polygons, Virtua Racing's "bleeding-edge 3D models, complex backdrops, and blistering framerate were unlike anything we’d ever seen". He added that it "allowed us to toggle between four different views, including chase cam and first-person view" which is "hard to imagine a modern racing game without" and said it "showed the masses what the future of racing games was going to look like".[49] In 2019, a Nintendo Life article by Ken Horowitz called it "one of the most influential coin-ops" of all time.[8]

Patent dispute

In 1992, Sega applied for a Japanese patent involving an innovative feature they developed for Virtua Racing: changing the 3D camera viewpoint with the press of a button. Sega also used the feature in later games such as Daytona USA. It took five years for the patent to process before the patent was successfully granted to Sega in 1997. By that time, camera change buttons had become a common feature in 3D video games. This would mean Sega could earn royalties from 3D video games that used a camera change button feature.[79]

Due to being a common feature used in many 3D video games, Sega received royalties from other companies using the feature in their games, both in Japan and internationally. Atari, for example, paid Sega royalties for using the feature in Atari Jaguar games. Sega also successfully took legal action against Nintendo, among other companies, for using the feature in their games. In the late 1990s, Nintendo and Sony Computer Entertainment decided to work together to challenge Sega's patent in Japanese courts. They found that the 3D camera change button feature of Virtua Racing was used in an earlier title, Star Wars: Attack on the Death Star, a Star Wars video game developed by Japanese company M.N.M Software (later called Mindware) for the Sharp X68000 computer and released exclusively for the Japanese market in 1991. That game's development was led by Mikito Ichikawa, who attended court to testify. Sega's patent was eventually revoked as a result of Ichikawa's testimony, but Ichikawa himself never received any compensation from Nintendo or other companies. However, Ichikawa revealed that the Star Wars game wasn't the first either, but the first game to use the feature was Magical Shot, a billiards game also developed by M.N.M Software for the X68000 and released exclusively for the Japanese market in 1991.[80]

References

- ↑ Famitsu DC (February 2002). Sega Arcade History. Enterbrain. pp. 125. https://retrocdn.net/images/3/35/Sega_Arcade_History_JP_EnterBrain_Book-1.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Electronic Gaming Monthly, issue 40 (November 1992), page 54

- ↑ Kline, Stephen; Dyer-Witheford, Nick; Peuter, Greig De (2003). Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7735-2591-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=gw5V10iLEsUC&pg=PA138.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Prescreen: Virtua Racing". Edge (6 (March 1994)): 32–3. January 27, 1994. https://retrocdn.net/images/9/9b/Edge_UK_006.pdf#page=32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Sega's Riding High: big sales for 'Virtua Racing' signal new era for Sega & the biz; Tom Petit & Ken Anderson explain how hi-tech is remaking coin-op". RePlay 18 (4): 75–83. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-18-issue-no.-4-january-1993-600DPI/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2018%2C%20Issue%20No.%204%20-%20January%201993/page/75.

- ↑ Andy Crane, Take That (December 17, 1992). "Feature: 'Take That' on Virtua Racing". Bad Influence!. Series 1. Episode 8. Event occurs at 9:36. ITV. CITV. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Computer and Video Games, issue 149 (April 1994), page 86

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Horowitz, Ken (May 6, 2019). "The History Of Virtua Racing, One Of The Most Influential Coin-Ops Of All Time". Nintendo Life. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2019/05/feature_the_history_of_virtua_racing_one_of_the_most_influential_coin-ops_of_all_time.

- ↑ "Pedal To The Metal: Sega Set To Speed, Swing, Sidekick Into The 1990s With New Fall Line". Vending Times 29 (10): 52–5. August 1989. https://archive.org/details/VendingTimesVOL29NO10August1989Clearscan/page/n47.

- ↑ "Sega Enterprises Ltd.". Lockheed Martin. 1996. http://www.real3d.com/sega.html.

- ↑ "Second Hand Smoke – One up, two down". Tom's Hardware. October 22, 1999. http://www.thg.ru/smoke/19991022/print.html.

- ↑ "Special Report: Tom Petit (Sega Enterprises)". RePlay 16 (4): 80, 82. January 1991. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-16-issue-no.-4-january-1991-600dpi/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2016%2C%20Issue%20No.%204%20-%20January%201991/page/44.

- ↑ "Sega's SVP Chip to be Sold Separately". GamePro (IDG) (67): 174. April 1994.

- ↑ "Virtua Racing (Genesis)". http://ign.com/games/virtua-racing/gen-6398.

- ↑ Digital Foundry (May 1, 2019). DF Retro: Virtua Racing Switch vs Every Console Port vs Model 1 Arcade!. Retrieved September 2, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Bob (2021-03-04). "Sega Saturn Virtua Racing Documentary" (in en-US). https://www.retrorgb.com/sega-saturn-virtua-racing-documentary.html.

- ↑ "Virtua Racing - Sega Saturn Review". 1996. https://www.csoon.com/issue13/vr_sat.htm.

- ↑ (in en) Sega Saturn Manual: V. R. Virtua Racing. Time Warner Interactive. 1995. pp. 10. https://archive.org/details/V._R._Virtua_Racing_1995_Time_Warner_Interactive_US/page/n5/mode/2up.

- ↑ "Time Warner Interactive's VR Virtua Racing" (in en). https://www.gamespot.com/games/time-warner-interactives-vr-virtua-racing/cheats/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Wong, Alistair (2019-04-25). "M2 Talks About The Long Process Of How Virtua Racing Ended Up On The Nintendo Switch" (in en-US). https://www.siliconera.com/m2-talks-about-the-long-process-of-how-virtua-racing-ended-up-on-the-nintendo-switch/.

- ↑ 株式会社インプレス (2019-04-25). "「SEGA AGES バーチャレーシング」本日発売! オンライン2P対戦とオフライン最大8P対戦がプレイできる" (in ja). https://game.watch.impress.co.jp/docs/news/1181544.html.

- ↑ "Review: SEGA AGES Virtua Racing - A Truly Historic Remaster Effort By M2". June 27, 2019. https://www.nintendolife.com/reviews/switch-eshop/sega_ages_virtua_racing. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ↑ Computer and Video Games, issue 152, pages 107–111

- ↑ Computer and Video Games, issue 157, pages 132–134

- ↑ "Virtua Racing". Edge (16): 88–89. January 1995. https://segaretro.org/index.php?title=File:Edge_UK_016.pdf&page=88. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Semdra, Ed; Carpenter, Danyon; Manuel, Al; Sushi-X (June 1994). "Review Crew". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Sendai Publishing) 7 (6): 33. ISSN 1058-918X. https://archive.gamehistory.org/item/5553408b-1354-4287-ae4f-cd2fd062f33a.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Saturn Virtua Racing (Sega Saturn) by Time Warner Int.". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis) (75): 124. October 1995.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "バーチャレーシング (メガドライブ)の関連情報 | ゲーム・エンタメ最新情報のファミ通.com". http://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?m=pc&a=page_h_title&title_id=7648.

- ↑ 読者 クロスレビュー: V.R.(バーチャレーシング). Weekly Famicom Tsūshin. No.299. Pg.38. September 9, 1994.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Diehard GameFan, volume 2, issue 7 (June 1994), page 24

- ↑ "File:HobbyConsolas ES 053.pdf - Retro CDN". https://retrocdn.net/index.php?title=File:HobbyConsolas_ES_053.pdf&page=99. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ↑ Humphreys, Andrew (March 1994). "Virtua Racing". Hyper (4): 22–24. https://archive.org/details/hyper-004/page/22/mode/2up.

- ↑ Hopkinson, Russell (April 1995). "Virtua Racing Deluxe". Hyper (17): 34–35. https://archive.org/details/hyper-017/page/34/mode/2up. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Finals". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (1): 93. January 1995.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Virtua Racing". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (12): 181. December 1995.

- ↑ Electronic Games, issue 57 (August 1994), page 84

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Maximum Reviews: Virtua Racing". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine (Emap International Limited) (3): 145. January 1996.

- ↑ Mega rating, issue 19, page 25, April 1994

- ↑ "Game Index". MegaTech (42 (June 1995)): 30–1. May 31, 1995. https://archive.org/details/megatech-42/page/n29/mode/2up.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Leadbetter, Richard (January 1996). "Review: Virtua Racing". Sega Saturn Magazine (Emap International Limited) (3): 88–89.

- ↑ "Virtua Racing Deluxe". Ultimate Future Games (2): 88–89. January 1995. https://archive.org/details/Ultimate_Future_Games_Issue_02_1995-01_Future_Publishing_GB/page/n77/mode/2up?q=%22killer+instinct%22. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Gamest, The Best Game 2: Gamest Mook, Vol. 112, pages 6–26

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "The AMOA Awards". RePlay 19 (2): 87. November 1993. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-19-issue-no.-2-november-1993/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2019%2C%20Issue%20No.%202%20-%20November%201993/page/87.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "CES Showstoppers". GamePro (IDG) (67): 74–81. April 1994.

- ↑ GameFan, volume 3, issue 1 (January 1995), pages 68–75

- ↑ "VideoGames Best of '94". VideoGames - The Ultimate Gaming Magazine (74 (March 1995)): 44–7. February 1995. https://archive.org/details/Video_Games_The_Ultimate_Gaming_Magazine_Issue_74_March_1995/page/n45/mode/2up.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Mega, issue 26 (November 1994), page 74

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Top 100 Games of All Time, Next Generation, September 1996, pages 66 and 68

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "The Top 10 Most Influential Racing Games Ever – IGN". April 3, 2015. http://ign.com/articles/2015/04/03/the-top-10-most-influential-racing-games-ever?page=2.

- ↑ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25 – アップライト, コックピット型TVゲーム機 (Upright/Cockpit Videos)". Game Machine (ja) (Amusement Press, Inc. (ja)) (436): 29. October 15, 1992.

- ↑ "Electronic Games 1993–03". March 1993. https://archive.org/stream/Electronic-Games-1993-03/Electronic%20Games%201993-03#page/n15/mode/1up.

- ↑ "RePlay: The Players' Choice". RePlay 18 (2): 4. November 1992. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-18-issue-no.-2-november-1992-600DPI/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2018%2C%20Issue%20No.%202%20-%20November%201992/page/4/mode/1up.

- ↑ "RePlay: The Players' Choice". RePlay 18 (3): 13. December 1992. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-18-issue-no.-3-december-1992-600DPI/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2018%2C%20Issue%20No.%203%20-%20December%201992%20%28Compressed%29/page/13.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops: Feb. 1993". Electronic Games 1 (7 (April 1993)): 12. March 16, 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-04/page/n11.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops of March 1993". Electronic Games 1 (8 (May 1993)): 14. April 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-05/page/n13.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops of April 1993". Electronic Games 1 (9 (June 1993)): 14. May 11, 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-06/page/n13.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops of May 1993". Electronic Games 1 (10 (July 1993)): 14. June 22, 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-07/page/n13.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops of June 1993". Electronic Games 1 (11 (August 1993)): 16. July 22, 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-08/page/n15.

- ↑ "Top Coin-Ops of July 1993". Electronic Games 1 (12 (September 1993)): 14. August 24, 1993. https://archive.org/details/Electronic-Games-1993-09/page/n13.

- ↑ "Electronic Games 1993–10". October 1993. https://archive.org/stream/Electronic-Games-1993-10/Electronic%20Games%201993-10#page/n13/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Electronic Games 1993–12". December 1993. https://archive.org/stream/Electronic-Games-1993-12/Electronic%20Games%201993-12#page/n16/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Game Center Poll: Top Games". RePlay 19 (2): 142. November 1993. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-19-issue-no.-2-november-1993/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2019%2C%20Issue%20No.%202%20-%20November%201993/page/142.

- ↑ "Count Down Hot 100: Hot 10!". Famicom Tsūshin (226): 83. April 16, 1993. https://archive.org/details/famitsu-issue-226-apr-1993/page/83.

- ↑ "The Bottom Line". RePlay 18 (4): 32, 34. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-18-issue-no.-4-january-1993-600DPI/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2018%2C%20Issue%20No.%204%20-%20January%201993/page/32.

- ↑ "Overseas Readers Column: "SF II: CE Turbo" And "Lethal Enforcers" Top". Game Machine (ja) (Amusement Press, Inc. (ja)) (464): 36. January 1–15, 1994. https://onitama.tv/gamemachine/pdf/19940101p.pdf#page=19.

- ↑ "ACME '94: Play Meter, AAMA salute best games". Play Meter 20 (5): ACME 73–4. April 1994. https://archive.org/details/play-meter-volume-20-number-5-april-1994/Play%20Meter%20-%20Volume%2020%2C%20Number%205%20-%20April%201994/page/n144.

- ↑ "AMOA Award Nominees: Game Awards". RePlay 19 (1): 59. October 1993. https://archive.org/details/re-play-volume-19-issue-no.-1-october-1993-600dpi/RePlay%20-%20Volume%2019%2C%20Issue%20No.%201%20-%20October%201993/page/n56/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Ação Games". https://archive.org/details/acao_games_50/acao_games_31/page/n33/mode/2up.

- ↑ "ProReview: Virtua Racing". GamePro (IDG) (69): 36–38. June 1994.

- ↑ Mega magazine issue 26, page 74, Maverick Magazines, November 1994

- ↑ "ProReview: Virtua Racing Deluxe". GamePro (IDG) (76): 60–61. January 1995.

- ↑ "ProReview: Virtua Racing". GamePro (IDG) (85): 50. October 1995.

- ↑ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux (Harris Publications) (4): 28. April 1995. https://archive.org/details/flux-issue-4/page/n29/mode/2up.

- ↑ "Top 100 Games of All Time". GamesMaster (44): 77. July 1996. https://retrocdn.net/images/c/cf/GamesMaster_UK_044.pdf.

- ↑ "Top 100 Sega Saturn Games". Saturn Power (9): 95. January 1998. https://retrocdn.net/images/7/70/SaturnPower_UK_09.pdf.

- ↑ "Top 100 Sega Saturn Games". Saturn Power (9): 95. January 1998. https://retrocdn.net/images/7/70/SaturnPower_UK_09.pdf.

- ↑ "Virtua Racing – Arcade (1992)". 15 Most Influential Games of All Time. GameSpot. March 14, 2001. http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/15influential/p13_01.html.

- ↑ "The Art of Virtua Fighter". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (11): 1. November 1995. https://archive.org/details/nextgen-issue-011/page/n1/mode/2up. "Then in 1992, he changed gaming forever with Virtua Racing. Overnight, 'polygons' became the buzz-word of the industry ...".

- ↑ "News: Japanese Patent Victory for Sega". Computer and Video Games (195 (February 1998)): 6–7. January 14, 1998. https://archive.org/details/Computer_and_Video_Games_Issue_195_1998-02_EMAP_Images_GB/page/n7/mode/2up.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (December 18, 2015). "How Star Wars Helped Nintendo Defeat One Of Sega's Most Ludicrous Patents". Nintendo Life. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2015/12/how_star_wars_helped_nintendo_defeat_one_of_segas_most_ludicrous_patents.

|