Solvable group

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, more specifically in the field of group theory, a solvable group or soluble group is a group that can be constructed from abelian groups using extensions. Equivalently, a solvable group is a group whose derived series terminates in the trivial subgroup.

Motivation

Historically, the word "solvable" arose from Galois theory and the proof of the general unsolvability of quintic equations. Specifically, a polynomial equation is solvable in radicals if and only if the corresponding Galois group is solvable[1] (note this theorem holds only in characteristic 0). This means associated to a polynomial

there is a tower of field extensions

such that

- where , so is a solution to the equation where

- contains a splitting field for

Example

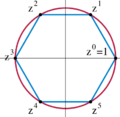

For example, the smallest Galois field extension of

containing the element

gives a solvable group. It has associated field extensions

giving a solvable group of Galois extensions containing the following composition factors:

- with group action , and minimal polynomial .

- with group action , and minimal polynomial .

- with group action , and minimal polynomial containing the 5th roots of unity excluding .

- with group action , and minimal polynomial .

, where is the identity permutation. All of the defining group actions change a single extension while keeping all of the other extensions fixed. For example, an element of this group is the group action . A general element in the group can be written as for a total of 80 elements.

It is worthwhile to note that this group is not abelian itself. For example:

In fact, in this group, . The solvable group is isometric to , defined using the semidirect product and direct product of the cyclic groups. In the solvable group, is not a normal subgroup.

Definition

A group G is called solvable if it has a subnormal series whose factor groups (quotient groups) are all abelian, that is, if there are subgroups 1 = G0 < G1 < ⋅⋅⋅ < Gk = G such that Gj−1 is normal in Gj, and Gj /Gj−1 is an abelian group, for j = 1, 2, ..., k.

Or equivalently, if its derived series, the descending normal series

where every subgroup is the commutator subgroup of the previous one, eventually reaches the trivial subgroup of G. These two definitions are equivalent, since for every group H and every normal subgroup N of H, the quotient H/N is abelian if and only if N includes the commutator subgroup of H. The least n such that G(n) = 1 is called the derived length of the solvable group G.

For finite groups, an equivalent definition is that a solvable group is a group with a composition series all of whose factors are cyclic groups of prime order. This is equivalent because a finite group has finite composition length, and every simple abelian group is cyclic of prime order. The Jordan–Hölder theorem guarantees that if one composition series has this property, then all composition series will have this property as well. For the Galois group of a polynomial, these cyclic groups correspond to nth roots (radicals) over some field. The equivalence does not necessarily hold for infinite groups: for example, since every nontrivial subgroup of the group Z of integers under addition is isomorphic to Z itself, it has no composition series, but the normal series {0, Z}, with its only factor group isomorphic to Z, proves that it is in fact solvable.

Examples

Abelian groups

The basic example of solvable groups are abelian groups. They are trivially solvable since a subnormal series is formed by just the group itself and the trivial group. But non-abelian groups may or may not be solvable.

Nilpotent groups

More generally, all nilpotent groups are solvable. In particular, finite p-groups are solvable, as all finite p-groups are nilpotent.

Quaternion groups

In particular, the quaternion group is a solvable group given by the group extension

where the kernel

is the subgroup generated by

.

Group extensions

Group extensions form the prototypical examples of solvable groups. That is, if

and

are solvable groups, then any extension

defines a solvable group

. In fact, all solvable groups can be formed from such group extensions.

Non-abelian group which is non-nilpotent

A small example of a solvable, non-nilpotent group is the symmetric group S3. In fact, as the smallest simple non-abelian group is A5, (the alternating group of degree 5) it follows that every group with order less than 60 is solvable.

Finite groups of odd order

The Feit–Thompson theorem states that every finite group of odd order is solvable. In particular this implies that if a finite group is simple, it is either a prime cyclic or of even order.

Non-example

The group S5 is not solvable — it has a composition series {E, A5, S5} (and the Jordan–Hölder theorem states that every other composition series is equivalent to that one), giving factor groups isomorphic to A5 and C2; and A5 is not abelian. Generalizing this argument, coupled with the fact that An is a normal, maximal, non-abelian simple subgroup of Sn for n > 4, we see that Sn is not solvable for n > 4. This is a key step in the proof that for every n > 4 there are polynomials of degree n which are not solvable by radicals (Abel–Ruffini theorem). This property is also used in complexity theory in the proof of Barrington's theorem.

Subgroups of GL2

Consider the subgroups

of

for some field

. Then, the group quotient

can be found by taking arbitrary elements in

, multiplying them together, and figuring out what structure this gives. So

Note the determinant condition on

implies

, hence

is a subgroup (which are the matrices where

). For fixed

, the linear equation

implies

, which is an arbitrary element in

since

. Since we can take any matrix in

and multiply it by the matrix

with

, we can get a diagonal matrix in

. This shows the quotient group

.

Remark

Notice that this description gives the decomposition of

as

where

acts on

by

. This implies

. Also, a matrix of the form

corresponds to the element

in the group.

Borel subgroups

For a linear algebraic group its Borel subgroup is defined as a subgroup which is closed, connected, and solvable in , and it is the maximal possible subgroup with these properties (note the first two are topological properties). For example, in and the group of upper-triangular, or lower-triangular matrices are two of the Borel subgroups. The example given above, the subgroup in is the Borel subgroup.

Borel subgroup in GL3

In

there are the subgroups

Notice

, hence the Borel group has the form

Borel subgroup in product of simple linear algebraic groups

In the product group

the Borel subgroup can be represented by matrices of the form

where

is an

upper triangular matrix and

is a

upper triangular matrix.

Z-groups

Any finite group whose p-Sylow subgroups are cyclic is a semidirect product of two cyclic groups, in particular solvable. Such groups are called Z-groups.

OEIS values

Numbers of solvable groups with order n are (start with n = 0)

- 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 5, 2, 2, 1, 5, 1, 2, 1, 14, 1, 5, 1, 5, 2, 2, 1, 15, 2, 2, 5, 4, 1, 4, 1, 51, 1, 2, 1, 14, 1, 2, 2, 14, 1, 6, 1, 4, 2, 2, 1, 52, 2, 5, 1, 5, 1, 15, 2, 13, 2, 2, 1, 12, 1, 2, 4, 267, 1, 4, 1, 5, 1, 4, 1, 50, ... (sequence A201733 in the OEIS)

Orders of non-solvable groups are

- 60, 120, 168, 180, 240, 300, 336, 360, 420, 480, 504, 540, 600, 660, 672, 720, 780, 840, 900, 960, 1008, 1020, 1080, 1092, 1140, 1176, 1200, 1260, 1320, 1344, 1380, 1440, 1500, ... (sequence A056866 in the OEIS)

Properties

Solvability is closed under a number of operations.

- If G is solvable, and H is a subgroup of G, then H is solvable.[2]

- If G is solvable, and there is a homomorphism from G onto H, then H is solvable; equivalently (by the first isomorphism theorem), if G is solvable, and N is a normal subgroup of G, then G/N is solvable.[3]

- The previous properties can be expanded into the following "three for the price of two" property: G is solvable if and only if both N and G/N are solvable.

- In particular, if G and H are solvable, the direct product G × H is solvable.

Solvability is closed under group extension:

- If H and G/H are solvable, then so is G; in particular, if N and H are solvable, their semidirect product is also solvable.

It is also closed under wreath product:

- If G and H are solvable, and X is a G-set, then the wreath product of G and H with respect to X is also solvable.

For any positive integer N, the solvable groups of derived length at most N form a subvariety of the variety of groups, as they are closed under the taking of homomorphic images, subalgebras, and (direct) products. The direct product of a sequence of solvable groups with unbounded derived length is not solvable, so the class of all solvable groups is not a variety.

Burnside's theorem

Burnside's theorem states that if G is a finite group of order paqb where p and q are prime numbers, and a and b are non-negative integers, then G is solvable.

Related concepts

Supersolvable groups

As a strengthening of solvability, a group G is called supersolvable (or supersoluble) if it has an invariant normal series whose factors are all cyclic. Since a normal series has finite length by definition, uncountable groups are not supersolvable. In fact, all supersolvable groups are finitely generated, and an abelian group is supersolvable if and only if it is finitely generated. The alternating group A4 is an example of a finite solvable group that is not supersolvable.

If we restrict ourselves to finitely generated groups, we can consider the following arrangement of classes of groups:

- cyclic < abelian < nilpotent < supersolvable < polycyclic < solvable < finitely generated group.

Virtually solvable groups

A group G is called virtually solvable if it has a solvable subgroup of finite index. This is similar to virtually abelian. Clearly all solvable groups are virtually solvable, since one can just choose the group itself, which has index 1.

Hypoabelian

A solvable group is one whose derived series reaches the trivial subgroup at a finite stage. For an infinite group, the finite derived series may not stabilize, but the transfinite derived series always stabilizes. A group whose transfinite derived series reaches the trivial group is called a hypoabelian group, and every solvable group is a hypoabelian group. The first ordinal α such that G(α) = G(α+1) is called the (transfinite) derived length of the group G, and it has been shown that every ordinal is the derived length of some group (Malcev 1949).

p-solvable

A finite group is p-solvable for some prime p if every factor in the composition series is a p-group or has order prime to p. A finite group is solvable iff it is p-solvable for every p. [4]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Milne. Field Theory. pp. 45. https://www.jmilne.org/math/CourseNotes/FT.pdf.

- ↑ Rotman (1995), Theorem 5.15, p. 102, at Google Books

- ↑ Rotman (1995), Theorem 5.16, p. 102, at Google Books

- ↑ "p-solvable-groups". https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/P-solvable_group.

References

- Malcev, A. I. (1949), "Generalized nilpotent algebras and their associated groups", Mat. Sbornik, New Series 25 (67): 347–366

- Rotman, Joseph J. (1995), An Introduction to the Theory of Groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 148 (4 ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-94285-8

External links

|