Special unitary group

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

| Group theory → Lie groups Lie groups |

|---|

|

In mathematics, the special unitary group of degree n, denoted SU(n), is the Lie group of n × n unitary matrices with determinant 1.

The matrices of the more general unitary group may have complex determinants with absolute value 1, rather than real 1 in the special case.

The group operation is matrix multiplication. The special unitary group is a normal subgroup of the unitary group U(n), consisting of all n×n unitary matrices. As a compact classical group, U(n) is the group that preserves the standard inner product on .[lower-alpha 1] It is itself a subgroup of the general linear group,

The SU(n) groups find wide application in the Standard Model of particle physics, especially SU(2) in the electroweak interaction and SU(3) in quantum chromodynamics.[1]

The simplest case, SU(1), is the trivial group, having only a single element. The group SU(2) is isomorphic to the group of quaternions of norm 1, and is thus diffeomorphic to the 3-sphere. Since unit quaternions can be used to represent rotations in 3-dimensional space (uniquely up to sign), there is a surjective homomorphism from SU(2) to the rotation group SO(3) whose kernel is {+I, −I}.[lower-alpha 2] Since the quaternions can be identified as the even subalgebra of the Clifford Algebra Cl(3), SU(2) is in fact identical to one of the symmetry groups of spinors, Spin(3), that enables a spinor presentation of rotations.

Properties

The special unitary group SU(n) is a strictly real Lie group (vs. a more general complex Lie group). Its dimension as a real manifold is n2 − 1. Topologically, it is compact and simply connected.[2] Algebraically, it is a simple Lie group (meaning its Lie algebra is simple; see below).[3]

The center of SU(n) is isomorphic to the cyclic group , and is composed of the diagonal matrices ζ I for ζ an nth root of unity and I the n × n identity matrix.

Its outer automorphism group for n ≥ 3 is while the outer automorphism group of SU(2) is the trivial group.

A maximal torus of rank n − 1 is given by the set of diagonal matrices with determinant 1. The Weyl group of SU(n) is the symmetric group Sn, which is represented by signed permutation matrices (the signs being necessary to ensure that the determinant is 1).

The Lie algebra of SU(n), denoted by , can be identified with the set of traceless anti‑Hermitian n × n complex matrices, with the regular commutator as a Lie bracket. Particle physicists often use a different, equivalent representation: The set of traceless Hermitian n × n complex matrices with Lie bracket given by −i times the commutator.

Lie algebra

The Lie algebra of consists of n × n skew-Hermitian matrices with trace zero.[4] This (real) Lie algebra has dimension n2 − 1. More information about the structure of this Lie algebra can be found below in § Lie algebra structure.

Fundamental representation

In the physics literature, it is common to identify the Lie algebra with the space of trace-zero Hermitian (rather than the skew-Hermitian) matrices. That is to say, the physicists' Lie algebra differs by a factor of from the mathematicians'. With this convention, one can then choose generators Ta that are traceless Hermitian complex n × n matrices, where:

where the f are the structure constants and are antisymmetric in all indices, while the d-coefficients are symmetric in all indices.

As a consequence, the commutator is:

and the corresponding anticommutator is:

The factor of i in the commutation relation arises from the physics convention and is not present when using the mathematicians' convention.

The conventional normalization condition is

The generators satisfy the Jacobi identity:[5]

By convention, in the physics literature the generators are defined as the traceless Hermitian complex matrices with a prefactor: for the group, the generators are chosen as where are the Pauli matrices, while for the case of one defines where are the Gell-Mann matrices.[6] With these definitions, the generators satisfy the following normalization condition:

Adjoint representation

In the (n2 − 1)-dimensional adjoint representation, the generators are represented by (n2 − 1) × (n2 − 1) matrices, whose elements are defined by the structure constants themselves:

The group SU(2)

Using matrix multiplication for the binary operation, SU(2) forms a group,[7]

where the overline denotes complex conjugation.

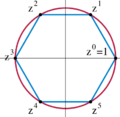

Diffeomorphism with the 3-sphere S3

If we consider as a pair in where and , then the equation becomes

This is the equation of the 3-sphere S3. This can also be seen using an embedding: the map

where denotes the set of 2 by 2 complex matrices, is an injective real linear map (by considering diffeomorphic to and diffeomorphic to ). Hence, the restriction of φ to the 3-sphere (since modulus is 1), denoted S3, is an embedding of the 3-sphere onto a compact submanifold of , namely φ(S3) = SU(2).

Therefore, as a manifold, S3 is diffeomorphic to SU(2), which shows that SU(2) is simply connected and that S3 can be endowed with the structure of a compact, connected Lie group.

Isomorphism with group of versors

Quaternions of norm 1 are called versors since they generate the rotation group SO(3): The SU(2) matrix:

can be mapped to the quaternion

This map is in fact a group isomorphism. Additionally, the determinant of the matrix is the squared norm of the corresponding quaternion. Clearly any matrix in SU(2) is of this form and, since it has determinant 1, the corresponding quaternion has norm 1. Thus SU(2) is isomorphic to the group of versors.[8]

Relation to spatial rotations

Every versor is naturally associated to a spatial rotation in 3 dimensions, and the product of versors is associated to the composition of the associated rotations. Furthermore, every rotation arises from exactly two versors in this fashion. In short: there is a 2:1 surjective homomorphism from SU(2) to SO(3); consequently SO(3) is isomorphic to the quotient group SU(2)/{±I}, the manifold underlying SO(3) is obtained by identifying antipodal points of the 3-sphere S3, and SU(2) is the universal cover of SO(3).

Lie algebra

The Lie algebra of SU(2) consists of 2 × 2 skew-Hermitian matrices with trace zero.[9] Explicitly, this means

The Lie algebra is then generated by the following matrices,

which have the form of the general element specified above.

This can also be written as using the Pauli matrices.

These satisfy the quaternion relationships and The commutator bracket is therefore specified by

The above generators are related to the Pauli matrices by and This representation is routinely used in quantum mechanics to represent the spin of fundamental particles such as electrons. They also serve as unit vectors for the description of our 3 spatial dimensions in loop quantum gravity. They also correspond to the Pauli X, Y, and Z gates, which are standard generators for the single qubit gates, corresponding to 3d rotations about the axes of the Bloch sphere.

The Lie algebra serves to work out the representations of SU(2).

SU(3)

The group SU(3) is an 8-dimensional simple Lie group consisting of all 3 × 3 unitary matrices with determinant 1.

Topology

The group SU(3) is a simply-connected, compact Lie group.[10] Its topological structure can be understood by noting that SU(3) acts transitively on the unit sphere in . The stabilizer of an arbitrary point in the sphere is isomorphic to SU(2), which topologically is a 3-sphere. It then follows that SU(3) is a fiber bundle over the base S5 with fiber S3. Since the fibers and the base are simply connected, the simple connectedness of SU(3) then follows by means of a standard topological result (the long exact sequence of homotopy groups for fiber bundles).[11]

The SU(2)-bundles over S5 are classified by since any such bundle can be constructed by looking at trivial bundles on the two hemispheres and looking at the transition function on their intersection, which is a copy of S4, so

Then, all such transition functions are classified by homotopy classes of maps

and as rather than , SU(3) cannot be the trivial bundle SU(2) × S5 ≅ S3 × S5, and therefore must be the unique nontrivial (twisted) bundle. This can be shown by looking at the induced long exact sequence on homotopy groups.

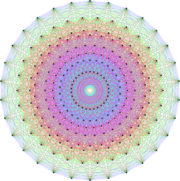

Representation theory

The representation theory of SU(3) is well-understood.[12] Descriptions of these representations, from the point of view of its complexified Lie algebra , may be found in the articles on Lie algebra representations or the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for SU(3).

Lie algebra

The generators, T, of the Lie algebra of SU(3) in the defining (particle physics, Hermitian) representation, are

where λa, the Gell-Mann matrices, are the SU(3) analog of the Pauli matrices for SU(2):

These λa span all traceless Hermitian matrices H of the Lie algebra, as required. Note that λ2, λ5, λ7 are antisymmetric.

They obey the relations

or, equivalently,

The f are the structure constants of the Lie algebra, given by

while all other fabc not related to these by permutation are zero. In general, they vanish unless they contain an odd number of indices from the set {2, 5, 7}.[lower-alpha 3]

The symmetric coefficients d take the values

They vanish if the number of indices from the set {2, 5, 7} is odd.

A generic SU(3) group element generated by a traceless 3×3 Hermitian matrix H, normalized as tr(H2) = 2, can be expressed as a second order matrix polynomial in H:[13]

LP where

Lie algebra structure

As noted above, the Lie algebra of SU(n) consists of n × n skew-Hermitian matrices with trace zero.[14]

The complexification of the Lie algebra is , the space of all n × n complex matrices with trace zero.[15] A Cartan subalgebra then consists of the diagonal matrices with trace zero,[16] which we identify with vectors in whose entries sum to zero. The roots then consist of all the n(n − 1) permutations of (1, −1, 0, ..., 0).

A choice of simple roots is

So, SU(n) is of rank n − 1 and its Dynkin diagram is given by An−1, a chain of n − 1 nodes: Script error: No such module "Dynkin"....Script error: No such module "Dynkin"..[17] Its Cartan matrix is

Its Weyl group or Coxeter group is the symmetric group Sn, the symmetry group of the (n − 1)-simplex.

Generalized special unitary group

For a field F, the generalized special unitary group over F, SU(p, q; F), is the group of all linear transformations of determinant 1 of a vector space of rank n = p + q over F which leave invariant a nondegenerate, Hermitian form of signature (p, q). This group is often referred to as the special unitary group of signature p q over F. The field F can be replaced by a commutative ring, in which case the vector space is replaced by a free module.

Specifically, fix a Hermitian matrix A of signature p q in , then all

satisfy

Often one will see the notation SU(p, q) without reference to a ring or field; in this case, the ring or field being referred to is and this gives one of the classical Lie groups. The standard choice for A when is

However, there may be better choices for A for certain dimensions which exhibit more behaviour under restriction to subrings of .

Example

An important example of this type of group is the Picard modular group which acts (projectively) on complex hyperbolic space of dimension two, in the same way that acts (projectively) on real hyperbolic space of dimension two. In 2005 Gábor Francsics and Peter Lax computed an explicit fundamental domain for the action of this group on HC2.[18]

A further example is , which is isomorphic to .

Important subgroups

In physics the special unitary group is used to represent fermionic symmetries. In theories of symmetry breaking it is important to be able to find the subgroups of the special unitary group. Subgroups of SU(n) that are important in GUT physics are, for p > 1, n − p > 1,

where × denotes the direct product and U(1), known as the circle group, is the multiplicative group of all complex numbers with absolute value 1.

For completeness, there are also the orthogonal and symplectic subgroups,

Since the rank of SU(n) is n − 1 and of U(1) is 1, a useful check is that the sum of the ranks of the subgroups is less than or equal to the rank of the original group. SU(n) is a subgroup of various other Lie groups,

See Spin group and Simple Lie group for E6, E7, and G2.

There are also the accidental isomorphisms: SU(4) = Spin(6), SU(2) = Spin(3) = Sp(1),[lower-alpha 4] and U(1) = Spin(2) = SO(2).

One may finally mention that SU(2) is the double covering group of SO(3), a relation that plays an important role in the theory of rotations of 2-spinors in non-relativistic quantum mechanics.

SU(1, 1)

where denotes the complex conjugate of the complex number u.

This group is isomorphic to SL(2,ℝ) and Spin(2,1)[19] where the numbers separated by a comma refer to the signature of the quadratic form preserved by the group. The expression in the definition of SU(1,1) is an Hermitian form which becomes an isotropic quadratic form when u and v are expanded with their real components.

An early appearance of this group was as the "unit sphere" of coquaternions (split-quaternions), introduced by James Cockle in 1852. Let

Then the 2×2 identity matrix, and and the elements i, j, and k all anticommute, as in quaternions. Also is still a square root of −I2 (negative of the identity matrix), whereas are not, unlike in quaternions. For both quaternions and coquaternions, all scalar quantities are treated as implicit multiples of I2 and notated as 1.

The coquaternion with scalar w, has conjugate similar to Hamilton's quaternions. The quadratic form is

Note that the 2-sheet hyperboloid corresponds to the imaginary units in the algebra so that any point p on this hyperboloid can be used as a pole of a sinusoidal wave according to Euler's formula.

The hyperboloid is stable under SU(1, 1), illustrating the isomorphism with Spin(2, 1). The variability of the pole of a wave, as noted in studies of polarization, might view elliptical polarization as an exhibit of the elliptical shape of a wave with pole . The Poincaré sphere model used since 1892 has been compared to a 2-sheet hyperboloid model,[20] and the practice of SU(1, 1) interferometry has been introduced.

When an element of SU(1, 1) is interpreted as a Möbius transformation, it leaves the unit disk stable, so this group represents the motions of the Poincaré disk model of hyperbolic plane geometry. Indeed, for a point [z, 1] in the complex projective line, the action of SU(1,1) is given by

since in projective coordinates

Writing complex number arithmetic shows

where

Therefore, so that their ratio lies in the open disk.[21]

See also

- Unitary group

- Projective special unitary group, PSU(n)

- Orthogonal group

- Generalizations of Pauli matrices

- Representation theory of SU(2)

Footnotes

- ↑ For a characterization of U(n) and hence SU(n) in terms of preservation of the standard inner product on , see Classical group.

- ↑ For an explicit description of the homomorphism SU(2) → SO(3), see Connection between SO(3) and SU(2).

- ↑ So fewer than 1⁄6 of all fabcs are non-vanishing.

- ↑ Sp(n) is the compact real form of . It is sometimes denoted USp(2n). The dimension of the Sp(n)-matrices is 2n × 2n.

Citations

- ↑ Halzen, Francis; Martin, Alan (1984). Quarks & Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-88741-2. https://archive.org/details/quarksleptonsint0000halz.

- ↑ Hall 2015, Proposition 13.11

- ↑ Wybourne, B.G. (1974). Classical Groups for Physicists. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0471965057.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Proposition 3.24

- ↑ Georgi, Howard (2018-05-04) (in en). Lie Algebras in Particle Physics: From Isospin to Unified Theories (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780429499210. ISBN 978-0-429-49921-0. Bibcode: 2018laip.book.....G. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780429499210.

- ↑ Georgi, Howard (2018-05-04) (in en). Lie Algebras in Particle Physics: From Isospin to Unified Theories (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780429499210. ISBN 978-0-429-49921-0. Bibcode: 2018laip.book.....G. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780429499210.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Exercise 1.5

- ↑ Savage, Alistair. "LieGroups". http://alistairsavage.ca/mat4144/notes/MAT4144-5158-LieGroups.pdf.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Proposition 3.24

- ↑ Hall 2015 Proposition 13.11

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 13.2

- ↑ Hall 2015 Chapter 6

- ↑ Rosen, S P (1971). "Finite Transformations in Various Representations of SU(3)". Journal of Mathematical Physics 12 (4): 673–681. doi:10.1063/1.1665634. Bibcode: 1971JMP....12..673R.; Curtright, T L; Zachos, C K (2015). "Elementary results for the fundamental representation of SU(3)". Reports on Mathematical Physics 76 (3): 401–404. doi:10.1016/S0034-4877(15)30040-9. Bibcode: 2015RpMP...76..401C.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Proposition 3.24

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 3.6

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 7.7.1

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 8.10.1

- ↑ Francsics, Gabor; Lax, Peter D. (September 2005). "An explicit fundamental domain for the Picard modular group in two complex dimensions". arXiv:math/0509708.

- ↑ Gilmore, Robert (1974). Lie Groups, Lie Algebras and some of their Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 52, 201−205.

- ↑ Mota, R.D.; Ojeda-Guillén, D.; Salazar-Ramírez, M.; Granados, V.D. (2016). "SU(1,1) approach to Stokes parameters and the theory of light polarization". Journal of the Optical Society of America B 33 (8): 1696–1701. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.33.001696. Bibcode: 2016JOSAB..33.1696M.

- ↑ Siegel, C. L. (1971). Topics in Complex Function Theory. 2. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 13–15. ISBN 0-471-79080 X.

References

- Hall, Brian C. (2015), Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 222 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3319134666

- Iachello, Francesco (2006), Lie Algebras and Applications, Lecture Notes in Physics, 708, Springer, ISBN 3540362363

|