Coproduct

In category theory, the coproduct, or categorical sum, is a construction which includes as examples the disjoint union of sets and of topological spaces, the free product of groups, and the direct sum of modules and vector spaces. The coproduct of a family of objects is essentially the "least specific" object to which each object in the family admits a morphism. It is the category-theoretic dual notion to the categorical product, which means the definition is the same as the product but with all arrows reversed. Despite this seemingly innocuous change in the name and notation, coproducts can be and typically are dramatically different from products.

Definition

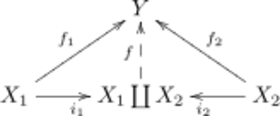

Let [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] be a category and let [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math] be objects of [math]\displaystyle{ C. }[/math] An object is called the coproduct of [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2, }[/math] written [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 \sqcup X_2, }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 \oplus X_2, }[/math] or sometimes simply [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 + X_2, }[/math] if there exist morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ i_1 : X_1 \to X_1 \sqcup X_2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ i_2 : X_2 \to X_1 \sqcup X_2 }[/math] satisfying the following universal property: for any object [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] and any morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 : X_1 \to Y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f_2 : X_2 \to Y, }[/math] there exists a unique morphism [math]\displaystyle{ f : X_1 \sqcup X_2 \to Y }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 = f \circ i_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f_2 = f \circ i_2. }[/math] That is, the following diagram commutes:

The unique arrow [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] making this diagram commute may be denoted [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 \sqcup f_2, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 \oplus f_2, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 + f_2, }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \left[f_1, f_2\right]. }[/math] The morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ i_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ i_2 }[/math] are called canonical injections, although they need not be injections or even monic.

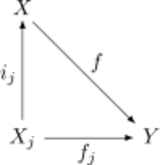

The definition of a coproduct can be extended to an arbitrary family of objects indexed by a set [math]\displaystyle{ J. }[/math] The coproduct of the family [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{ X_j : j \in J \right\} }[/math] is an object [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] together with a collection of morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ i_j : X_j \to X }[/math] such that, for any object [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] and any collection of morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ f_j : X_j \to Y }[/math] there exists a unique morphism [math]\displaystyle{ f : X \to Y }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ f_j = f \circ i_j. }[/math] That is, the following diagram commutes for each [math]\displaystyle{ j \in J }[/math]:

The coproduct [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] of the family [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{ X_j \right\} }[/math] is often denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \coprod_{j\in J}X_j }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \bigoplus_{j \in J} X_j. }[/math]

Sometimes the morphism [math]\displaystyle{ f : X \to Y }[/math] may be denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \coprod_{j \in J} f_j }[/math] to indicate its dependence on the individual [math]\displaystyle{ f_j }[/math]s.

Examples

The coproduct in the category of sets is simply the disjoint union with the maps ij being the inclusion maps. Unlike direct products, coproducts in other categories are not all obviously based on the notion for sets, because unions don't behave well with respect to preserving operations (e.g. the union of two groups need not be a group), and so coproducts in different categories can be dramatically different from each other. For example, the coproduct in the category of groups, called the free product, is quite complicated. On the other hand, in the category of abelian groups (and equally for vector spaces), the coproduct, called the direct sum, consists of the elements of the direct product which have only finitely many nonzero terms. (It therefore coincides exactly with the direct product in the case of finitely many factors.)

Given a commutative ring R, the coproduct in the category of commutative R-algebras is the tensor product. In the category of (noncommutative) R-algebras, the coproduct is a quotient of the tensor algebra (see free product of associative algebras).

In the case of topological spaces, coproducts are disjoint unions with their disjoint union topologies. That is, it is a disjoint union of the underlying sets, and the open sets are sets open in each of the spaces, in a rather evident sense. In the category of pointed spaces, fundamental in homotopy theory, the coproduct is the wedge sum (which amounts to joining a collection of spaces with base points at a common base point).

The concept of disjoint union secretly underlies the above examples: the direct sum of abelian groups is the group generated by the "almost" disjoint union (disjoint union of all nonzero elements, together with a common zero), similarly for vector spaces: the space spanned by the "almost" disjoint union; the free product for groups is generated by the set of all letters from a similar "almost disjoint" union where no two elements from different sets are allowed to commute. This pattern holds for any variety in the sense of universal algebra.

The coproduct in the category of Banach spaces with short maps is the l1 sum, which cannot be so easily conceptualized as an "almost disjoint" sum, but does have a unit ball almost-disjointly generated by the unit ball is the cofactors.[1]

The coproduct of a poset category is the join operation.

Discussion

The coproduct construction given above is actually a special case of a colimit in category theory. The coproduct in a category [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] can be defined as the colimit of any functor from a discrete category [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] into [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math]. Not every family [math]\displaystyle{ \lbrace X_j\rbrace }[/math] will have a coproduct in general, but if it does, then the coproduct is unique in a strong sense: if [math]\displaystyle{ i_j:X_j\rightarrow X }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k_j:X_j\rightarrow Y }[/math] are two coproducts of the family [math]\displaystyle{ \lbrace X_j\rbrace }[/math], then (by the definition of coproducts) there exists a unique isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ f:X\rightarrow Y }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ f \circ i_j = k_j }[/math] for each [math]\displaystyle{ j \in J }[/math].

As with any universal property, the coproduct can be understood as a universal morphism. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta : C\rightarrow C\times C }[/math] be the diagonal functor which assigns to each object [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] the ordered pair [math]\displaystyle{ \left(X, X\right) }[/math] and to each morphism [math]\displaystyle{ f : X\rightarrow Y }[/math] the pair [math]\displaystyle{ \left(f, f\right) }[/math]. Then the coproduct [math]\displaystyle{ X + Y }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is given by a universal morphism to the functor [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] from the object [math]\displaystyle{ \left(X, Y\right) }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ C\times C }[/math].

The coproduct indexed by the empty set (that is, an empty coproduct) is the same as an initial object in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math].

If [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] is a set such that all coproducts for families indexed with [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] exist, then it is possible to choose the products in a compatible fashion so that the coproduct turns into a functor [math]\displaystyle{ C^J\rightarrow C }[/math]. The coproduct of the family [math]\displaystyle{ \lbrace X_j\rbrace }[/math] is then often denoted by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \coprod_{j\in J} X_j }[/math]

and the maps [math]\displaystyle{ i_j }[/math] are known as the natural injections.

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Hom}_C\left(U, V\right) }[/math] denote the set of all morphisms from [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] (that is, a hom-set in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math]), we have a natural isomorphism

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Hom}_C\left(\coprod_{j\in J}X_j,Y\right) \cong \prod_{j\in J}\operatorname{Hom}_C(X_j,Y) }[/math]

given by the bijection which maps every tuple of morphisms

- [math]\displaystyle{ (f_j)_{j\in J} \in \prod_{j \in J}\operatorname{Hom}(X_j,Y) }[/math]

(a product in Set, the category of sets, which is the Cartesian product, so it is a tuple of morphisms) to the morphism

- [math]\displaystyle{ \coprod_{j\in J} f_j \in \operatorname{Hom}\left(\coprod_{j\in J}X_j,Y\right). }[/math]

That this map is a surjection follows from the commutativity of the diagram: any morphism [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is the coproduct of the tuple

- [math]\displaystyle{ (f\circ i_j)_{j \in J}. }[/math]

That it is an injection follows from the universal construction which stipulates the uniqueness of such maps. The naturality of the isomorphism is also a consequence of the diagram. Thus the contravariant hom-functor changes coproducts into products. Stated another way, the hom-functor, viewed as a functor from the opposite category [math]\displaystyle{ C^\operatorname{op} }[/math] to Set is continuous; it preserves limits (a coproduct in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is a product in [math]\displaystyle{ C^\operatorname{op} }[/math]).

If [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] is a finite set, say [math]\displaystyle{ J = \lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace }[/math], then the coproduct of objects [math]\displaystyle{ X_1,\ldots,X_n }[/math] is often denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ X_1\oplus\ldots\oplus X_n }[/math]. Suppose all finite coproducts exist in C, coproduct functors have been chosen as above, and 0 denotes the initial object of C corresponding to the empty coproduct. We then have natural isomorphisms

- [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus (Y \oplus Z)\cong (X\oplus Y)\oplus Z\cong X\oplus Y\oplus Z }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus 0 \cong 0\oplus X \cong X }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus Y \cong Y\oplus X. }[/math]

These properties are formally similar to those of a commutative monoid; a category with finite coproducts is an example of a symmetric monoidal category.

If the category has a zero object [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math], then we have a unique morphism [math]\displaystyle{ X\rightarrow Z }[/math] (since [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math] is terminal) and thus a morphism [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus Y\rightarrow Z\oplus Y }[/math]. Since [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math] is also initial, we have a canonical isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ Z\oplus Y\cong Y }[/math] as in the preceding paragraph. We thus have morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus Y\rightarrow X }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus Y\rightarrow Y }[/math], by which we infer a canonical morphism [math]\displaystyle{ X\oplus Y\rightarrow X\times Y }[/math]. This may be extended by induction to a canonical morphism from any finite coproduct to the corresponding product. This morphism need not in general be an isomorphism; in Grp it is a proper epimorphism while in Set* (the category of pointed sets) it is a proper monomorphism. In any preadditive category, this morphism is an isomorphism and the corresponding object is known as the biproduct. A category with all finite biproducts is known as a semiadditive category.

If all families of objects indexed by [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] have coproducts in [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math], then the coproduct comprises a functor [math]\displaystyle{ C^J\rightarrow C }[/math]. Note that, like the product, this functor is covariant.

See also

References

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 5 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98403-8.

External links

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of coproducts in the category of finite sets. Written by Jocelyn Paine.

|