Engineering:STS-28

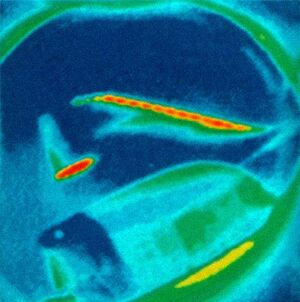

Infrared view of Columbia's left wing during reentry, photographed by the SILTS experiment. | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-28 STS-28R |

|---|---|

| Mission type | DoD satellites deployment |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1989-061A |

| SATCAT no. | 20164 |

| Mission duration | 5 days, 1 hour, 0 minutes, 8 seconds (achieved) |

| Distance travelled | 3,400,000 km (2,100,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 81 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Landing mass | 90,816 kg (200,215 lb) |

| Payload mass | 19,600 kg (43,200 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | August 8, 1989, 12:37:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center, LC-39B |

| Contractor | Rockwell International |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | August 13, 1989, 13:37:08 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Air Force Base, Runway 17 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 289 km (180 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 306 km (190 mi) |

| Inclination | 57.00° |

| Period | 90.50 minutes |

| Instruments | |

| |

STS-28 mission patch  Standing: Mark N. Brown, James C. Adamson Seated: Richard N. Richards, Brewster H. Shaw, David Leestma | |

STS-28 was the 30th NASA Space Shuttle mission, the fourth shuttle mission dedicated to United States Department of Defense (DoD) purposes, and the eighth flight of Space Shuttle Columbia. The mission launched on August 8, 1989, and traveled 3,400,000 km (2,100,000 mi) during 81 orbits of the Earth, before landing on runway 17 of Edwards Air Force Base, California , on August 13, 1989. STS-28 was also Columbia's first flight since January 1986, when it had flown STS-61-C, the mission directly preceding the Challenger disaster of STS-51-L. The mission details of STS-28 are classified, but the payload is widely believed to have been the first SDS-2 relay communications satellite. The altitude of the mission was between 295 km (183 mi) and 307 km (191 mi).[1]

The mission was officially designated STS-28R as the original STS-28 designator belonged to STS-51-J, the 21st Space Shuttle mission. Official documentation for that mission contained the designator STS-28 throughout. As STS-51-L was designated STS-33, future flights with the STS-26 through STS-33 designators would require the R in their documentation to avoid conflicts in tracking data from one mission to another.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Brewster H. Shaw Third and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Richard N. Richards First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | James C. Adamson First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | David Leestma Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Mark N. Brown First spaceflight | |

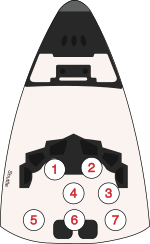

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[2] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Shaw | Shaw | |

| S2 | Richards | Richards | |

| S3 | Adamson | Brown | |

| S4 | Leestma | Leestma | |

| S5 | Brown | Adamson |

Mission summary

Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) lifted off from Pad 39B, Launch Complex 39 at Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on August 8, 1989. The launch took place at 8:37:00 a.m. EDT.

During STS-28, Columbia deployed two satellites: USA-40[3] and USA-41.[4] Early reports speculated that STS-28's primary payload was an Advanced KH-11 photo-reconnaissance satellite. Later reports, and amateur satellite observations, suggest that USA-40 was instead a second-generation Satellite Data System (SDS) relay,[5] similar to those likely launched on STS-38 and STS-53. These satellites had the same bus design as the LEASAT satellites deployed on other shuttle missions, and were likely deployed in the same fashion.[citation needed]

The mission marked the first flight of a 5 kg (11 lb) human skull, which served as the primary element of "Detailed Secondary Objective 469", also known as the In-flight Radiation Dose Distribution (IDRD) experiment. This joint NASA/DoD experiment was designed to examine the penetration of radiation into the human cranium during spaceflight. The female skull was seated in a plastic matrix, representative of tissue, and sliced into ten layers. Hundreds of thermoluminescent dosimeters were mounted in the skull's layers to record radiation levels at multiple depths. This experiment, which also flew on STS-36 and STS-31, was located in the shuttle's mid-deck lockers on all three flights, recording radiation levels at different orbital inclinations.[6]

During the flight, the crew shut down a thruster in the reaction control system (RCS) after receiving indications of a leak. An RCS heater also malfunctioned during the flight. Post-flight analysis of STS-28 discovered unusual heating of the thermal protection system (TPS) during re-entry, caused by an early transition to turbulent plasma flow around the vehicle. A detailed report identified protruding gap filler as the likely cause.[7] This filler material was the same material that was removed during a spacewalk during STS-114, the Space Shuttle's post-Columbia disaster Return to Flight mission, in 2005.

The Shuttle Lee-side Temperature Sensing (SILTS) infrared camera package made its second flight aboard Columbia on this mission. The cylindrical pod and surrounding black tiles on the orbiter's vertical stabilizer housed an imaging system, designed to map thermodynamic conditions during reentry, on the surfaces visible from the top of the tail fin. Ironically, the camera faced the port wing of Columbia, which was breached by superheated plasma on its disastrous final flight, destroying the wing and, later, the orbiter. The SILTS system was used for only six missions before being deactivated, but the pod remained for the duration of Columbia's career.[8] Columbia's thermal protection system was also upgraded to a similar configuration as Discovery and Atlantis in between the loss of Challenger and STS-28, with many of the white LRSI tiles replaced with felt insulation blankets in order to reduce weight and turnaround time. One other minor modification that debuted on STS-28 was the move of Columbia's name from its payload bay doors to the fuselage, allowing the orbiter to be easily recognized while in orbit.

Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 9:37:08 a.m. EDT on August 13, 1989, after a mission lasting 5 days, 1 hour, 0 minutes, and 8 seconds. Because of a software glitch with the weight-on-wheels sensors installed on the landing gear, the crew was instructed to touch down on the runway as softly as possible. This instruction resulted in a touchdown airspeed of 154 knots, the slowest of the entire Shuttle program by a wide margin and barely above the Orbiter's stall speed[9]

Gallery

Alaska's Saint Elias Mountains and Malaspina Glacier imaged from orbit.

See also

References

- ↑ "STS-28 payload". https://www.space-track.org/basicspacedata/query/class/satcat/intldes/1989-061A/current/y/format/html/emptyresult/show.

- ↑ "STS-28". Spacefacts. http://spacefacts.de/mission/english/sts-28.htm.

- ↑ "1989-061B". NASA. https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1989-061B.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "1989-061C". National Space Science Data Center. https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1989-061C.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Cassutt, Michael (August 2009). "Secret Space Shuttles". Air & Space magazine. http://www.airspacemag.com/space/secret-space-shuttles-35318554/?all.

- ↑ Macknight, Nigel, Space Year 1991, p. 41 ISBN:0-87938-482-4

- ↑ "STS-28R – Early Boundary Layer Transition". http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/news/columbia/sts28r_earlyboundary.pdf.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Shuttle Infrared Leeside Temperature Sensing[|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Hale, Wayne (29 July 2015). "Pilot Error is Never Root Cause". https://waynehale.wordpress.com/2015/07/29/pilot-error-is-never-root-cause/.

External links

|