Astronomy:Perturbation

| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

In astronomy, perturbation is the complex motion of a massive body subjected to forces other than the gravitational attraction of a single other massive body.[1] The other forces can include a third (fourth, fifth, etc.) body, resistance, as from an atmosphere, and the off-center attraction of an oblate or otherwise misshapen body.[2]

Introduction

The study of perturbations began with the first attempts to predict planetary motions in the sky. In ancient times the causes were unknown. Isaac Newton, at the time he formulated his laws of motion and of gravitation, applied them to the first analysis of perturbations,[2] recognizing the complex difficulties of their calculation.[3] Many of the great mathematicians since then have given attention to the various problems involved; throughout the 18th and 19th centuries there was demand for accurate tables of the position of the Moon and planets for marine navigation.

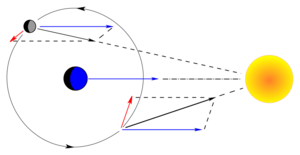

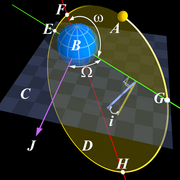

The complex motions of gravitational perturbations can be broken down. The hypothetical motion that the body follows under the gravitational effect of one other body only is a conic section, and can be described in geometrical terms. This is called a two-body problem, or an unperturbed Keplerian orbit. The differences between that and the actual motion of the body are perturbations due to the additional gravitational effects of the remaining body or bodies. If there is only one other significant body then the perturbed motion is a three-body problem; if there are multiple other bodies it is an n-body problem. A general analytical solution (a mathematical expression to predict the positions and motions at any future time) exists for the two-body problem; when more than two bodies are considered analytic solutions exist only for special cases. Even the two-body problem becomes insoluble if one of the bodies is irregular in shape.[4]

Most systems that involve multiple gravitational attractions present one primary body which is dominant in its effects (for example, a star, in the case of the star and its planet, or a planet, in the case of the planet and its satellite). The gravitational effects of the other bodies can be treated as perturbations of the hypothetical unperturbed motion of the planet or satellite around its primary body.

Mathematical analysis

General perturbations

In methods of general perturbations, general differential equations, either of motion or of change in the orbital elements, are solved analytically, usually by series expansions. The result is usually expressed in terms of algebraic and trigonometric functions of the orbital elements of the body in question and the perturbing bodies. This can be applied generally to many different sets of conditions, and is not specific to any particular set of gravitating objects.[5] Historically, general perturbations were investigated first. The classical methods are known as variation of the elements, variation of parameters or variation of the constants of integration. In these methods, it is considered that the body is always moving in a conic section, however the conic section is constantly changing due to the perturbations. If all perturbations were to cease at any particular instant, the body would continue in this (now unchanging) conic section indefinitely; this conic is known as the osculating orbit and its orbital elements at any particular time are what are sought by the methods of general perturbations.[2]

General perturbations takes advantage of the fact that in many problems of celestial mechanics, the two-body orbit changes rather slowly due to the perturbations; the two-body orbit is a good first approximation. General perturbations is applicable only if the perturbing forces are about one order of magnitude smaller, or less, than the gravitational force of the primary body.[4] In the Solar System, this is usually the case; Jupiter, the second largest body, has a mass of about 1/1000 that of the Sun.

General perturbation methods are preferred for some types of problems, as the source of certain observed motions are readily found. This is not necessarily so for special perturbations; the motions would be predicted with similar accuracy, but no information on the configurations of the perturbing bodies (for instance, an orbital resonance) which caused them would be available.[4]

Special perturbations

In methods of special perturbations, numerical datasets, representing values for the positions, velocities and accelerative forces on the bodies of interest, are made the basis of numerical integration of the differential equations of motion.[6] In effect, the positions and velocities are perturbed directly, and no attempt is made to calculate the curves of the orbits or the orbital elements.[2]

Special perturbations can be applied to any problem in celestial mechanics, as it is not limited to cases where the perturbing forces are small.[4] Once applied only to comets and minor planets, special perturbation methods are now the basis of the most accurate machine-generated planetary ephemerides of the great astronomical almanacs.[2][7] Special perturbations are also used for modeling an orbit with computers.

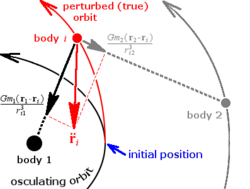

Cowell's formulation

Cowell's formulation (so named for Philip H. Cowell, who, with A.C.D. Cromellin, used a similar method to predict the return of Halley's comet) is perhaps the simplest of the special perturbation methods.[8] In a system of [math]\displaystyle{ \ n\ }[/math] mutually interacting bodies, this method mathematically solves for the Newtonian forces on body [math]\displaystyle{ \ i\ }[/math] by summing the individual interactions from the other [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] bodies:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\ddot{r}}_i = \sum_{\underset{j \ne i}{j=1}}^n \ G\ m_j \frac{\ (\mathbf{r}_j-\mathbf{r}_i)\ }{\ \| \mathbf{r}_j-\mathbf{r}_i \|^3 } }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \ \mathbf{\ddot{r}}_i\ }[/math] is the acceleration vector of body [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is the gravitational constant, [math]\displaystyle{ \ m_j\ }[/math] is the mass of body [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \ \mathbf{r}_i\ }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ \mathbf{r}_j\ }[/math] are the position vectors of objects [math]\displaystyle{ \ i\ }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ j\ }[/math] respectively, and [math]\displaystyle{ \ r_{ij} \equiv \| \mathbf{r}_j-\mathbf{r}_i \|\ }[/math] is the distance from object [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] to object [math]\displaystyle{ \ j\ }[/math], all vectors being referred to the barycenter of the system. This equation is resolved into components in [math]\displaystyle{ \ x\ , }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \ y\ , }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ z\ , }[/math] and these are integrated numerically to form the new velocity and position vectors. This process is repeated as many times as necessary. The advantage of Cowell's method is ease of application and programming. A disadvantage is that when perturbations become large in magnitude (as when an object makes a close approach to another) the errors of the method also become large.[9] However, for many problems in celestial mechanics, this is never the case. Another disadvantage is that in systems with a dominant central body, such as the Sun, it is necessary to carry many significant digits in the arithmetic because of the large difference in the forces of the central body and the perturbing bodies, although with high precision numbers built into modern computers this is not as much of a limitation as it once was.[10]

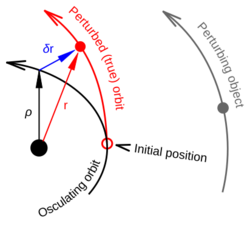

Encke's method

Encke's method begins with the osculating orbit as a reference and integrates numerically to solve for the variation from the reference as a function of time.[11] Its advantages are that perturbations are generally small in magnitude, so the integration can proceed in larger steps (with resulting lesser errors), and the method is much less affected by extreme perturbations. Its disadvantage is complexity; it cannot be used indefinitely without occasionally updating the osculating orbit and continuing from there, a process known as rectification.[9] Encke's method is similar to the general perturbation method of variation of the elements, except the rectification is performed at discrete intervals rather than continuously.[12]

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\rho} }[/math] be the radius vector of the osculating orbit, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] the radius vector of the perturbed orbit, and [math]\displaystyle{ \delta \mathbf{r} }[/math] the variation from the osculating orbit,

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \delta \mathbf{r} = \mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho} }[/math], and the equation of motion of [math]\displaystyle{ \delta \mathbf{r} }[/math] is simply

()

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{\delta \mathbf{r}} = \mathbf{\ddot{r}} - \boldsymbol{\ddot{\rho}} }[/math].

()

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\ddot{r}} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\ddot{\rho}} }[/math] are just the equations of motion of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\rho}, }[/math]

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\ddot{r}} = \mathbf{a}_{\text{per}} - {\mu \over r^3} \mathbf{r} }[/math] for the perturbed orbit and

()

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\ddot{\rho}} = - {\mu \over \rho^3} \boldsymbol{\rho} }[/math] for the unperturbed orbit,

()

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = G(M+m) }[/math] is the gravitational parameter with [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] the masses of the central body and the perturbed body, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{a}_{\text{per}} }[/math] is the perturbing acceleration, and [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] are the magnitudes of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\rho} }[/math].

Substituting from equations (3) and (4) into equation (2),

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{\delta \mathbf{r}} = \mathbf{a}_{\text{per}} + \mu \left( {\boldsymbol{\rho} \over \rho^3} - {\mathbf{r} \over r^3} \right), }[/math]

()

which, in theory, could be integrated twice to find [math]\displaystyle{ \delta \mathbf{r} }[/math]. Since the osculating orbit is easily calculated by two-body methods, [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\rho} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \delta \mathbf{r} }[/math] are accounted for and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] can be solved. In practice, the quantity in the brackets, [math]\displaystyle{ {\boldsymbol{\rho} \over \rho^3} - {\mathbf{r} \over r^3} }[/math], is the difference of two nearly equal vectors, and further manipulation is necessary to avoid the need for extra significant digits.[13][14] Encke's method was more widely used before the advent of modern computers, when much orbit computation was performed on mechanical calculating machines.

Periodic nature

In the Solar System, many of the disturbances of one planet by another are periodic, consisting of small impulses each time a planet passes another in its orbit. This causes the bodies to follow motions that are periodic or quasi-periodic – such as the Moon in its strongly perturbed orbit, which is the subject of lunar theory. This periodic nature led to the discovery of Neptune in 1846 as a result of its perturbations of the orbit of Uranus.

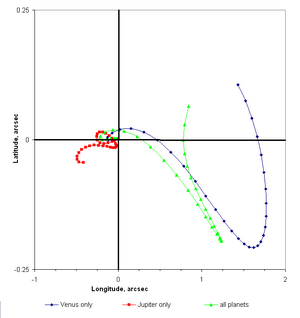

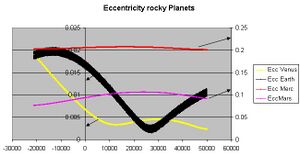

On-going mutual perturbations of the planets cause long-term quasi-periodic variations in their orbital elements, most apparent when two planets' orbital periods are nearly in sync. For instance, five orbits of Jupiter (59.31 years) is nearly equal to two of Saturn (58.91 years). This causes large perturbations of both, with a period of 918 years, the time required for the small difference in their positions at conjunction to make one complete circle, first discovered by Laplace.[2] Venus currently has the orbit with the least eccentricity, i.e. it is the closest to circular, of all the planetary orbits. In 25,000 years' time, Earth will have a more circular (less eccentric) orbit than Venus. It has been shown that long-term periodic disturbances within the Solar System can become chaotic over very long time scales; under some circumstances one or more planets can cross the orbit of another, leading to collisions.[15]

The orbits of many of the minor bodies of the Solar System, such as comets, are often heavily perturbed, particularly by the gravitational fields of the gas giants. While many of these perturbations are periodic, others are not, and these in particular may represent aspects of chaotic motion. For example, in April 1996, Jupiter's gravitational influence caused the period of Comet Hale–Bopp's orbit to decrease from 4,206 to 2,380 years, a change that will not revert on any periodic basis.[16]

See also

- Formation and evolution of the Solar System

- Frozen orbit

- Molniya orbit

- Nereid one of the outer moons of Neptune with a high orbital eccentricity of ~0.75 and is frequently perturbed

- Osculating orbit

- Orbit modeling

- Orbital resonance

- Proper orbital elements

- Stability of the Solar System

References

- Bibliography

- Bate, Roger R.; Mueller, Donald D.; White, Jerry E. (1971). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-60061-0. https://archive.org/details/fundamentalsofas00bate.

- Moulton, Forest Ray (1914). An Introduction to Celestial Mechanics (2nd revised ed.). Macmillan. https://archive.org/details/anintroductiont04moulgoog.

- Roy, A. E. (1988). Orbital Motion (3rd ed.). Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-85274-229-0.

- Footnotes

- ↑ Bate, Mueller, White (1971): ch. 9, p. 385.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Moulton (1914): ch. IX

- ↑ Newton in 1684 wrote: "By reason of the deviation of the Sun from the center of gravity, the centripetal force does not always tend to that immobile center, and hence the planets neither move exactly in ellipses nor revolve twice in the same orbit. Each time a planet revolves it traces a fresh orbit, as in the motion of the Moon, and each orbit depends on the combined motions of all the planets, not to mention the action of all these on each other. But to consider simultaneously all these causes of motion and to define these motions by exact laws admitting of easy calculation exceeds, if I am not mistaken, the force of any human mind." (quoted by Prof G E Smith (Tufts University), in "Three Lectures on the Role of Theory in Science" 1. Closing the loop: Testing Newtonian Gravity, Then and Now); and Prof R F Egerton (Portland State University, Oregon) after quoting the same passage from Newton concluded: "Here, Newton identifies the "many body problem" which remains unsolved analytically."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Roy (1988): ch. 6, 7.

- ↑ Bate, Mueller, White (1971): p. 387; sec. 9.4.3, p. 410.

- ↑ Bate, Mueller, White (1971), pp. 387–409.

- ↑ See, for instance, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Development Ephemeris.

- ↑ Cowell, P.H.; Crommelin, A.C.D. (1910). "Investigation of the Motion of Halley's Comet from 1759 to 1910". Greenwich Observations in Astronomy (Bellevue, for His Majesty's Stationery Office: Neill & Co.) 71: O1. Bibcode: 1911GOAMM..71O...1C.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Danby, J.M.A. (1988). Fundamentals of Celestial Mechanics (2nd ed.). Willmann-Bell, Inc.. chapter 11. ISBN 0-943396-20-4.

- ↑ Herget, Paul (1948). The Computation of Orbits. author published. p. 91 ff.

- ↑ Encke, J. F. (1854). Über die allgemeinen Störungen der Planeten. pp. 319–397. https://books.google.com/books?id=t5VCAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Battin (1999), sec. 10.2.

- ↑ Bate, Mueller, White (1971), sec. 9.3.

- ↑ Roy (1988), sec. 7.4.

- ↑ see references at Stability of the Solar System

- ↑ Don Yeomans (1997-04-10). "Comet Hale–Bopp Orbit and Ephemeris Information". JPL/NASA. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/comet/ephemjpl8.html.

Further reading

- P.E. El'Yasberg: Introduction to the Theory of Flight of Artificial Earth Satellites

External links

- Solex (by Aldo Vitagliano) predictions for the position/orbit/close approaches of Mars

- Gravitation Sir George Biddell Airy's 1884 book on gravitational motion and perturbations, using little or no math.(at Google books)