Spherical coordinate system

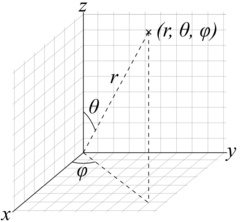

In mathematics, a spherical coordinate system is a coordinate system for three-dimensional space where the position of a given point in space is specified by three numbers, (r, θ, φ): the radial distance of the radial line r connecting the point to the fixed point of origin (which is located on a fixed polar axis, or zenith direction axis, or z-axis); the polar angle θ of the radial line r; and the azimuthal angle φ of the radial line r.

The polar angle θ is measured between the z-axis and the radial line r. The azimuthal angle φ is measured between the orthogonal projection of the radial line r onto the reference x-y-plane—which is orthogonal to the z-axis and passes through the fixed point of origin—and either of the fixed x-axis or y-axis, both of which are orthogonal to the z-axis and to each other. (See graphic re the "physics convention".)

Once the radius is fixed, the three coordinates (r, θ, φ), known as a 3-tuple, provide a coordinate system on a sphere, typically called the spherical polar coordinates. Nota bene: the physics convention is followed in this article; (See both graphics re "physics convention" and re "mathematics convention").

The radial distance from the fixed point of origin is also called the radius, or radial line, or radial coordinate. The polar angle may be called inclination angle, zenith angle, normal angle, or the colatitude. The user may choose to ignore the inclination angle and use the elevation angle instead, which is measured upward between the reference plane and the radial line—i.e., from the reference plane upward (towards to the positive z-axis) to the radial line. The depression angle is the negative of the elevation angle. (See graphic re the "physics convention"—not "mathematics convention".)

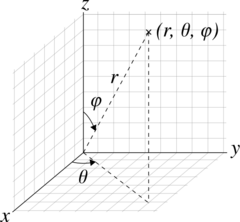

Both the use of symbols and the naming order of tuple coordinates differ among the several sources and disciplines. This article will use the ISO convention[1] frequently encountered in physics, where the naming tuple gives the order as: radial distance, polar angle, azimuthal angle, or [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math]. (See graphic re the "physics convention".) In contrast, the conventions in many mathematics books and texts give the naming order differently as: radial distance, "azimuthal angle", "polar angle", and [math]\displaystyle{ (\rho,\theta,\varphi) }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math]—which switches the uses and meanings of symbols θ and φ. Other conventions may also be used, such as r for a radius from the z-axis that is not from the point of origin. Particular care must be taken to check the meaning of the symbols.

According to the conventions of geographical coordinate systems, positions are measured by latitude, longitude, and height (altitude). There are a number of celestial coordinate systems based on different fundamental planes and with different terms for the various coordinates. The spherical coordinate systems used in mathematics normally use radians rather than degrees; (note 90 degrees equals π/2 radians). And these systems of the mathematics convention may measure the azimuthal angle counterclockwise (i.e., from the south direction x-axis, or 180°, towards the east direction y-axis, or +90°)—rather than measure clockwise (i.e., from the north direction x-axis, or 0°, towards the east direction y-axis, or +90°), as done in the horizontal coordinate system.[2] (See graphic re "mathematics convention".)

The spherical coordinate system of the physics convention can be seen as a generalization of the polar coordinate system in three-dimensional space. It can be further extended to higher-dimensional spaces, and is then referred to as a hyperspherical coordinate system.

Definition

To define a spherical coordinate system, one must designate an origin point in space, O, and two orthogonal directions: the zenith reference direction and the azimuth reference direction. These choices determine a reference plane that is typically defined as containing the point of origin and the x– and y–axes, either of which may be designated as the azimuth reference direction. The reference plane is perpendicular (orthogonal) to the zenith direction, and typically is desiginated "horizontal" to the zenith direction's "vertical". The spherical coordinates of a point P then are defined as follows:

- The radius or radial distance is the Euclidean distance from the origin O to P.

- The inclination (or polar angle) is the signed angle from the zenith reference direction to the line segment OP. (Elevation may be used as the polar angle instead of inclination; see below.)

- The azimuth (or azimuthal angle) is the signed angle measured from the azimuth reference direction to the orthogonal projection of the radial line segment OP on the reference plane.

The sign of the azimuth is determined by designating the rotation that is the positive sense of turning about the zenith. This choice is arbitrary, and is part of the coordinate system definition. (If the inclination is either zero or 180 degrees (= π radians), the azimuth is arbitrary. If the radius is zero, both azimuth and inclination are arbitrary.)

The elevation is the signed angle from the x-y reference plane to the radial line segment OP, where positive angles are designated as upward, towards the zenith reference. Elevation is 90 degrees (= π/2 radians) minus inclination. Thus, if the inclination is 60 degrees (= π/3 radians), then the elevation is 30 degrees (= π/6 radians).

In linear algebra, the vector from the origin O to the point P is often called the position vector of P.

Conventions

Several different conventions exist for representing spherical coordinates and prescribing the naming order of their symbols. The 3-tuple number set [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math] denotes radial distance, the polar angle—"inclination", or as the alternative, "elevation"—and the azimuthal angle. It is the common practice within the physics convention, as specified by ISO standard 80000-2:2019, and earlier in ISO 31-11 (1992).

As stated above, this article describes the ISO "physics convention"—unless otherwise noted.

However, some authors (including mathematicians) use the symbol ρ (rho) for radius, or radial distance, φ for inclination (or elevation) and θ for azimuth—while others keep the use of r for the radius; all which "provides a logical extension of the usual polar coordinates notation".[3] As to order, some authors list the azimuth before the inclination (or the elevation) angle. Some combinations of these choices result in a left-handed coordinate system. The standard "physics convention" 3-tuple set [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math] conflicts with the usual notation for two-dimensional polar coordinates and three-dimensional cylindrical coordinates, where θ is often used for the azimuth.[3]

Angles are typically measured in degrees (°) or in radians (rad), where 360° = 2π rad. The use of degrees is most common in geography, astronomy, and engineering, where radians are commonly used in mathematics and theoretical physics. The unit for radial distance is usually determined by the context, as occurs in applications of the 'unit sphere', see #Applications.

When the system is used to designate physical three-space, it is customary to assign positive to azimuth angles measured in the counterclockwise sense from the reference direction on the reference plane—as seen from the "zenith" side of the plane. This convention is used in particular for geographical coordinates, where the "zenith" direction is north and the positive azimuth (longitude) angles are measured eastwards from some prime meridian.

| coordinates set order | corresponding local geographical directions (Z, X, Y) |

right/left-handed |

|---|---|---|

| (r, θinc, φaz,right) | (U, S, E) | right |

| (r, φaz,right, θel) | (U, E, N) | right |

| (r, θel, φaz,right) | (U, N, E) | left |

Note: Easting (E), Northing (N), Upwardness (U). In the case of (U, S, E) the local azimuth angle would be measured counterclockwise from S to E.

Unique coordinates

Any spherical coordinate triplet (or tuple) [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math] specifies a single point of three-dimensional space. On the reverse view, any single point has infinitely many equivalent spherical coordinates. That is, the user can add or subtract any number of full turns to the angular measures without changing the angles themselves, and therefore without changing the point. It is convenient in many contexts to use negative radial distances, the convention being [math]\displaystyle{ (-r,-\theta,\varphi) }[/math], which is equivalent to [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi) }[/math] for any r, θ, and φ. Moreover, [math]\displaystyle{ (r,-\theta,\varphi) }[/math] is equivalent to [math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta,\varphi{+}180^\circ) }[/math].

When necessary to define a unique set of spherical coordinates for each point, the user must restrict the range, aka interval, of each coordinate. A common choice is:

- radial distance: r ≥ 0,

- polar angle: 0° ≤ θ ≤ 180°, or 0 rad ≤ θ ≤ π rad,

- azimuth : 0° ≤ φ < 360°, or 0 rad ≤ φ < 2π rad.

But instead of the interval [0°, 360°), the azimuth φ is typically restricted to the half-open interval (−180°, +180°], or (−π, +π ] radians, which is the standard convention for geographic longitude.

For the polar angle θ, the range (interval) for inclination is [0°, 180°], which is equivalent to elevation range (interval) [−90°, +90°]. In geography, the latitude is the elevation.

Even with these restrictions, if the polar angle (inclination) is 0° or 180°—elevation is −90° or +90°—then the azimuth angle is arbitrary; and if r is zero, both azimuth and polar angles are arbitrary. To define the coordinates as unique, the user can assert the convention that (in these cases) the arbitrary coordinates are set to zero.

Plotting

To plot any dot from its spherical coordinates (r, θ, φ), where θ is inclination, the user would: move r units from the origin in the zenith reference direction (z-axis); then rotate by the amount of the azimuth angle (φ) about the origin from the designated azimuth reference direction, (i.e., either the x– or y–axis, see Definition, above); and then rotate from the z-axis by the amount of the θ angle.

Applications

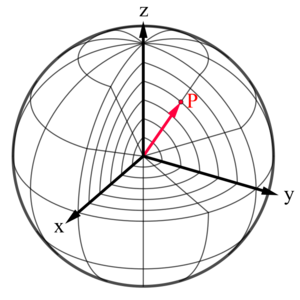

Just as the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system is useful—has a wide set of applications—on a planar surface, a two-dimensional spherical coordinate system is useful on the surface of a sphere. For example, one sphere that is described in Cartesian coordinates with the equation x2 + y2 + z2 = c2 can be described in spherical coordinates by the simple equation r = c. (In this system—shown here in the mathematics convention—the sphere is adapted as a unit sphere, where the radius is set to unity and then can generally be ignored, see graphic.)

This (unit sphere) simplification is also useful when dealing with objects such as rotational matrices. Spherical coordinates are also useful in analyzing systems that have some degree of symmetry about a point, including: volume integrals inside a sphere; the potential energy field surrounding a concentrated mass or charge; or global weather simulation in a planet's atmosphere.

Three dimensional modeling of loudspeaker output patterns can be used to predict their performance. A number of polar plots are required, taken at a wide selection of frequencies, as the pattern changes greatly with frequency. Polar plots help to show that many loudspeakers tend toward omnidirectionality at lower frequencies.

An important application of spherical coordinates provides for the separation of variables in two partial differential equations—the Laplace and the Helmholtz equations—that arise in many physical problems.The angular portions of the solutions to such equations take the form of spherical harmonics. Another application is ergonomic design, where r is the arm length of a stationary person and the angles describe the direction of the arm as it reaches out. The spherical coordinate system is also commonly used in 3D game development to rotate the camera around the player's position[4]

In geography

Instead of inclination, the geographic coordinate system uses elevation angle (or latitude), in the range (aka domain) −90° ≤ φ ≤ 90° and rotated north from the equator plane. Latitude (i.e., the angle of latitude) may be either geocentric latitude, measured (rotated) from the Earth's center—and designated variously by ψ, q, φ′, φc, φg—or geodetic latitude, measured (rotated) from the observer's local vertical, and typically designated φ. The polar angle (inclination), which is 90° minus the latitude and ranges from 0 to 180°, is called colatitude in geography.

The azimuth angle (or longitude) of a given position on Earth, commonly denoted by λ, is measured in degrees east or west from some conventional reference meridian (most commonly the IERS Reference Meridian); thus its domain (or range) is −180° ≤ λ ≤ 180° and a given reading is typically designated "East" or "West". For positions on the Earth or other solid celestial body, the reference plane is usually taken to be the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

Instead of the radial distance r geographers commonly use altitude above or below some local reference surface (vertical datum), which, for example, may be the mean sea level. When needed, the radial distance can be computed from the altitude by adding the radius of Earth, which is approximately 6,360 ± 11 km (3,952 ± 7 miles).

However, modern geographical coordinate systems are quite complex, and the positions implied by these simple formulae may be inaccurate by several kilometers. The precise standard meanings of latitude, longitude and altitude are currently defined by the World Geodetic System (WGS), and take into account the flattening of the Earth at the poles (about 21 km or 13 miles) and many other details.

Planetary coordinate systems use formulations analogous to the geographic coordinate system.

In astronomy

A series of astronomical coordinate systems are used to measure the elevation angle from several fundamental planes. These reference planes include: the observer's horizon, the galactic equator (defined by the rotation of the Milky Way), the celestial equator (defined by Earth's rotation), the plane of the ecliptic (defined by Earth's orbit around the Sun), and the plane of the earth terminator (normal to the instantaneous direction to the Sun).

Coordinate system conversions

As the spherical coordinate system is only one of many three-dimensional coordinate systems, there exist equations for converting coordinates between the spherical coordinate system and others.

Cartesian coordinates

The spherical coordinates of a point in the ISO convention (i.e. for physics: radius r, inclination θ, azimuth φ) can be obtained from its Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) by the formulae

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} r &= \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2} \\ \theta &= \arccos\frac{z}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}} = \arccos\frac{z}{r}= \begin{cases} \arctan\frac{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}{z} &\text{if } z \gt 0 \\ \pi +\arctan\frac{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}{z} &\text{if } z \lt 0 \\ +\frac{\pi}{2} &\text{if } z = 0 \text{ and } xy \neq 0 \\ \text{undefined} &\text{if } x=y=z = 0 \\ \end{cases} \\ \varphi &= \sgn(y)\arccos\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}} = \begin{cases} \arctan(\frac{y}{x}) &\text{if } x \gt 0, \\ \arctan(\frac{y}{x}) + \pi &\text{if } x \lt 0 \text{ and } y \geq 0, \\ \arctan(\frac{y}{x}) - \pi &\text{if } x \lt 0 \text{ and } y \lt 0, \\ +\frac{\pi}{2} &\text{if } x = 0 \text{ and } y \gt 0, \\ -\frac{\pi}{2} &\text{if } x = 0 \text{ and } y \lt 0, \\ \text{undefined} &\text{if } x = 0 \text{ and } y = 0. \end{cases} \end{align} }[/math]

The inverse tangent denoted in φ = arctan y/x must be suitably defined, taking into account the correct quadrant of (x, y). See the article on atan2.

Alternatively, the conversion can be considered as two sequential rectangular to polar conversions: the first in the Cartesian xy plane from (x, y) to (R, φ), where R is the projection of r onto the xy-plane, and the second in the Cartesian zR-plane from (z, R) to (r, θ). The correct quadrants for φ and θ are implied by the correctness of the planar rectangular to polar conversions.

These formulae assume that the two systems have the same origin, that the spherical reference plane is the Cartesian xy plane, that θ is inclination from the z direction, and that the azimuth angles are measured from the Cartesian x axis (so that the y axis has φ = +90°). If θ measures elevation from the reference plane instead of inclination from the zenith the arccos above becomes an arcsin, and the cos θ and sin θ below become switched.

Conversely, the Cartesian coordinates may be retrieved from the spherical coordinates (radius r, inclination θ, azimuth φ), where r ∈ [0, ∞), θ ∈ [0, π], φ ∈ [0, 2π), by [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} x &= r \sin\theta \, \cos\varphi, \\ y &= r \sin\theta \, \sin\varphi, \\ z &= r \cos\theta. \end{align} }[/math]

Cylindrical coordinates

Cylindrical coordinates (axial radius ρ, azimuth φ, elevation z) may be converted into spherical coordinates (central radius r, inclination θ, azimuth φ), by the formulas

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} r &= \sqrt{\rho^2 + z^2}, \\ \theta &= \arctan\frac{\rho}{z} = \arccos\frac{z}{\sqrt{\rho^2 + z^2}}, \\ \varphi &= \varphi. \end{align} }[/math]

Conversely, the spherical coordinates may be converted into cylindrical coordinates by the formulae

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \rho &= r \sin \theta, \\ \varphi &= \varphi, \\ z &= r \cos \theta. \end{align} }[/math]

These formulae assume that the two systems have the same origin and same reference plane, measure the azimuth angle φ in the same senses from the same axis, and that the spherical angle θ is inclination from the cylindrical z axis.

Generalization

It is also possible to deal with ellipsoids in Cartesian coordinates by using a modified version of the spherical coordinates.

Let P be an ellipsoid specified by the level set

[math]\displaystyle{ ax^2 + by^2 + cz^2 = d. }[/math]

The modified spherical coordinates of a point in P in the ISO convention (i.e. for physics: radius r, inclination θ, azimuth φ) can be obtained from its Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) by the formulae

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} x &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{a}} r \sin\theta \, \cos\varphi, \\ y &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{b}} r \sin\theta \, \sin\varphi, \\ z &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{c}} r \cos\theta, \\ r^{2} &= ax^2 + by^2 + cz^2. \end{align} }[/math]

An infinitesimal volume element is given by

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}V = \left|\frac{\partial(x, y, z)}{\partial(r, \theta, \varphi)}\right| \, dr\,d\theta\,d\varphi = \frac{1}{\sqrt{abc}} r^2 \sin \theta \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi = \frac{1}{\sqrt{abc}} r^2 \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\Omega. }[/math]

The square-root factor comes from the property of the determinant that allows a constant to be pulled out from a column:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{vmatrix} ka & b & c \\ kd & e & f \\ kg & h & i \end{vmatrix} = k \begin{vmatrix} a & b & c \\ d & e & f \\ g & h & i \end{vmatrix}. }[/math]

Integration and differentiation in spherical coordinates

The following equations (Iyanaga 1977) assume that the colatitude θ is the inclination from the positive z axis, as in the physics convention discussed.

The line element for an infinitesimal displacement from (r, θ, φ) to (r + dr, θ + dθ, φ + dφ) is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}\mathbf{r} = \mathrm{d}r\,\hat{\mathbf r} + r\,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\hat{\boldsymbol\theta } + r \sin{\theta} \, \mathrm{d}\varphi\,\mathbf{\hat{\boldsymbol\varphi}}, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \hat{\mathbf r} &= \sin \theta \cos \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf x} + \sin \theta \sin \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf y} + \cos \theta \,\hat{\mathbf z}, \\ \hat{\boldsymbol\theta} &= \cos \theta \cos \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf x} + \cos \theta \sin \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf y} - \sin \theta \,\hat{\mathbf z}, \\ \hat{\boldsymbol\varphi} &= - \sin \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf x} + \cos \varphi \,\hat{\mathbf y} \end{align} }[/math] are the local orthogonal unit vectors in the directions of increasing r, θ, and φ, respectively, and x̂, ŷ, and ẑ are the unit vectors in Cartesian coordinates. The linear transformation to this right-handed coordinate triplet is a rotation matrix, [math]\displaystyle{ R = \begin{pmatrix} \sin\theta\cos\varphi&\sin\theta\sin\varphi&\hphantom{-}\cos\theta\\ \cos\theta\cos\varphi&\cos\theta\sin\varphi&-\sin\theta\\ -\sin\varphi&\cos\varphi &\hphantom{-}0 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

This gives the transformation from the spherical to the cartesian, the other way around is given by its inverse. Note: the matrix is an orthogonal matrix, that is, its inverse is simply its transpose.

The Cartesian unit vectors are thus related to the spherical unit vectors by: [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{bmatrix}\mathbf{\hat x} \\ \mathbf{\hat y} \\ \mathbf{\hat z} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \sin\theta\cos\varphi & \cos\theta\cos\varphi & -\sin\varphi \\ \sin\theta\sin\varphi & \cos\theta\sin\varphi & \hphantom{-}\cos\varphi \\ \cos\theta & -\sin\theta & \hphantom{-}0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \boldsymbol{\hat{r}} \\ \boldsymbol{\hat\theta} \\ \boldsymbol{\hat\varphi} \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

The general form of the formula to prove the differential line element, is[5] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}\mathbf{r} = \sum_i \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x_i} \,\mathrm{d}x_i = \sum_i \left|\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x_i}\right| \frac{\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x_i}}{\left|\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x_i}\right|} \, \mathrm{d}x_i = \sum_i \left|\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x_i}\right| \,\mathrm{d}x_i \, \hat{\boldsymbol{x}}_i, }[/math] that is, the change in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf r }[/math] is decomposed into individual changes corresponding to changes in the individual coordinates.

To apply this to the present case, one needs to calculate how [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf r }[/math] changes with each of the coordinates. In the conventions used, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} = \begin{bmatrix} r \sin\theta \, \cos\varphi \\ r \sin\theta \, \sin\varphi \\ r \cos\theta \end{bmatrix}. }[/math]

Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial r} = \begin{bmatrix} \sin\theta \, \cos\varphi \\ \sin\theta \, \sin\varphi \\ \cos\theta \end{bmatrix}=\mathbf{\hat r}, \quad \frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial \theta} = \begin{bmatrix} r \cos\theta \, \cos\varphi \\ r \cos\theta \, \sin\varphi \\ -r \sin\theta \end{bmatrix}=r\,\hat{\boldsymbol\theta }, \quad \frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial \varphi} = \begin{bmatrix} -r \sin\theta \, \sin\varphi \\ \hphantom{-}r \sin\theta \, \cos\varphi \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = r \sin\theta\,\mathbf{\hat{\boldsymbol\varphi}} . }[/math]

The desired coefficients are the magnitudes of these vectors:[5] [math]\displaystyle{ \left|\frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial r}\right| = 1, \quad \left|\frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial \theta}\right| = r, \quad \left|\frac{\partial\mathbf r}{\partial \varphi}\right| = r \sin\theta. }[/math]

The surface element spanning from θ to θ + dθ and φ to φ + dφ on a spherical surface at (constant) radius r is then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}S_r = \left\|\frac{\partial {\mathbf r}}{\partial \theta} \times \frac{\partial {\mathbf r}}{\partial \varphi}\right\| \mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi = \left|r {\hat \boldsymbol\theta} \times r \sin \theta {\boldsymbol\hat \varphi} \right|= r^2 \sin\theta \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi ~. }[/math]

Thus the differential solid angle is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}\Omega = \frac{\mathrm{d}S_r}{r^2} = \sin\theta \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi. }[/math]

The surface element in a surface of polar angle θ constant (a cone with vertex the origin) is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}S_\theta = r \sin\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi \,\mathrm{d}r. }[/math]

The surface element in a surface of azimuth φ constant (a vertical half-plane) is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}S_\varphi = r \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\theta. }[/math]

The volume element spanning from r to r + dr, θ to θ + dθ, and φ to φ + dφ is specified by the determinant of the Jacobian matrix of partial derivatives, [math]\displaystyle{ J =\frac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(r,\theta,\varphi)} =\begin{pmatrix} \sin\theta\cos\varphi & r\cos\theta\cos\varphi & -r\sin\theta\sin\varphi\\ \sin\theta\sin\varphi & r\cos\theta\sin\varphi & \hphantom{-}r\sin\theta\cos\varphi\\ \cos\theta & -r\sin\theta & \hphantom{-}0 \end{pmatrix}, }[/math] namely [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}V = \left|\frac{\partial(x, y, z)}{\partial(r, \theta, \varphi)}\right| \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi= r^2 \sin\theta \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi = r^2 \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\Omega ~. }[/math]

Thus, for example, a function f(r, θ, φ) can be integrated over every point in R3 by the triple integral [math]\displaystyle{ \int\limits_0^{2\pi} \int\limits_0^\pi \int\limits_0^\infty f(r, \theta, \varphi) r^2 \sin\theta \,\mathrm{d}r \,\mathrm{d}\theta \,\mathrm{d}\varphi ~. }[/math]

The del operator in this system leads to the following expressions for the gradient and Laplacian for scalar fields, [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \nabla f &= {\partial f \over \partial r}\hat{\mathbf r} + {1 \over r}{\partial f \over \partial \theta}\hat{\boldsymbol\theta} + {1 \over r\sin\theta}{\partial f \over \partial \varphi}\hat{\boldsymbol\varphi}, \\[8pt] \nabla^2 f &= {1 \over r^2}{\partial \over \partial r} \left(r^2 {\partial f \over \partial r}\right) + {1 \over r^2 \sin\theta}{\partial \over \partial \theta} \left(\sin\theta {\partial f \over \partial \theta}\right) + {1 \over r^2 \sin^2\theta}{\partial^2 f \over \partial \varphi^2} \\[8pt] & = \left(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r^2} + \frac{2}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\right) f + {1 \over r^2 \sin\theta}{\partial \over \partial \theta} \left(\sin\theta \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}\right) f + \frac{1}{r^2 \sin^2\theta}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \varphi^2}f ~, \\[8pt] \end{align} }[/math]And it leads to the following expressions for the divergence and curl of vector fields,

[math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \cdot \mathbf{A} = \frac{1}{r^2}{\partial \over \partial r}\left( r^2 A_r \right) + \frac{1}{r \sin\theta}{\partial \over \partial\theta} \left( \sin\theta A_\theta \right) + \frac{1}{r \sin \theta} {\partial A_\varphi \over \partial \varphi}, }[/math][math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \nabla \times \mathbf{A} = {} & \frac{1}{r\sin\theta} \left[{\partial \over \partial \theta} \left( A_\varphi\sin\theta \right) - {\partial A_\theta \over \partial \varphi}\right] \hat{\mathbf r} \\[4pt] & {} + \frac 1 r \left[{1 \over \sin\theta}{\partial A_r \over \partial \varphi} - {\partial \over \partial r} \left( r A_\varphi \right) \right] \hat{\boldsymbol\theta} \\[4pt] & {} + \frac 1 r \left[{\partial \over \partial r} \left( r A_\theta \right) - {\partial A_r \over \partial \theta}\right] \hat{\boldsymbol\varphi}, \end{align} }[/math]

Further, the inverse Jacobian in Cartesian coordinates is [math]\displaystyle{ J^{-1} = \begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{x}{r}&\dfrac{y}{r}&\dfrac{z}{r}\\\\ \dfrac{xz}{r^2\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}&\dfrac{yz}{r^2\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}&\dfrac{-\left(x^2 + y^2\right)}{r^2\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}\\\\ \dfrac{-y}{x^2+y^2}&\dfrac{x}{x^2+y^2}&0 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] The metric tensor in the spherical coordinate system is [math]\displaystyle{ g = J^T J }[/math].

Distance in spherical coordinates

In spherical coordinates, given two points with φ being the azimuthal coordinate [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\mathbf r} &= (r,\theta,\varphi), \\ {\mathbf r'} &= (r',\theta',\varphi') \end{align} }[/math] The distance between the two points can be expressed as [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\mathbf D} &= \sqrt{r^2+r'^2-2rr'(\sin{\theta}\sin{\theta'}\cos{(\varphi-\varphi')} + \cos{\theta}\cos{\theta'})} \end{align} }[/math]

Kinematics

In spherical coordinates, the position of a point or particle (although better written as a triple[math]\displaystyle{ (r,\theta, \varphi) }[/math]) can be written as[6] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} = r \mathbf{\hat r} . }[/math] Its velocity is then[6] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{r}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \dot{r} \mathbf{\hat r} + r\,\dot\theta\,\hat{\boldsymbol\theta } + r\,\dot\varphi \sin\theta\,\mathbf{\hat{\boldsymbol\varphi}} }[/math] and its acceleration is[6] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{a} = {} & \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{v}}{\mathrm{d}t} \\[1ex] = {} & \hphantom{+}\; \left( \ddot{r} - r\,\dot\theta^2 - r\,\dot\varphi^2\sin^2\theta \right)\mathbf{\hat r} \\ & {} + \left( r\,\ddot\theta + 2\dot{r}\,\dot\theta - r\,\dot\varphi^2\sin\theta\cos\theta \right) \hat{\boldsymbol\theta } \\ & {} + \left( r\ddot\varphi\,\sin\theta + 2\dot{r}\,\dot\varphi\,\sin\theta + 2 r\,\dot\theta\,\dot\varphi\,\cos\theta \right) \hat{\boldsymbol\varphi} \end{align} }[/math]

The angular momentum is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{L} = \mathbf{r} \times \mathbf{p} = \mathbf{r} \times m\mathbf{v} = m r^2 \left(- \dot\varphi \sin\theta\,\mathbf{\hat{\boldsymbol\theta}} + \dot\theta\,\hat{\boldsymbol\varphi }\right) }[/math] Where [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is mass. In the case of a constant φ or else θ = π/2, this reduces to vector calculus in polar coordinates.

The corresponding angular momentum operator then follows from the phase-space reformulation of the above, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{L}= -i\hbar ~\mathbf{r} \times \nabla =i \hbar \left(\frac{\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}{\sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial}{\partial\phi} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\phi}} \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\right). }[/math]

The torque is given as[6] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\tau} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{L}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \mathbf{r} \times \mathbf{F} = -m \left(2r\dot{r}\dot{\varphi}\sin\theta + r^2\ddot{\varphi}\sin{\theta} + 2r^2\dot{\theta}\dot{\varphi}\cos{\theta} \right)\hat{\boldsymbol\theta} + m \left(r^2\ddot{\theta} + 2r\dot{r}\dot{\theta} - r^2\dot{\varphi}^2\sin\theta\cos\theta \right) \hat{\boldsymbol\varphi} }[/math]

The kinetic energy is given as[6] [math]\displaystyle{ E_k = \frac{1}{2}m \left[ \left(\dot{r}^2\right) + \left(r\dot{\theta}\right)^2 + \left(r\dot{\varphi}\sin\theta\right)^2 \right] }[/math]

See also

- Celestial coordinate system

- Coordinate system – Method for specifying point positions

- Del in cylindrical and spherical coordinates – Mathematical gradient operator in certain coordinate systems

- Double Fourier sphere method

- Elevation (ballistics) – Angle in ballistics

- Euler angles – Description of the orientation of a rigid body

- Gimbal lock – Loss of one degree of freedom in a three-dimensional, three-gimbal mechanism

- Hypersphere – N-sphere embedded in an (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space

- Jacobian matrix and determinant – Matrix of all first-order partial derivatives of a vector-valued function

- List of canonical coordinate transformations

- Sphere – Set of points equidistant from a center

- Spherical harmonic

- Theodolite

- Vector fields in cylindrical and spherical coordinates – Vector field representation in 3D curvilinear coordinate systems

- Yaw, pitch, and roll

Notes

- ↑ "ISO 80000-2:2019 Quantities and units – Part 2: Mathematics" (in en). 19 May 2020. pp. 20–21. https://www.iso.org/standard/64973.html.

- ↑ Duffett-Smith, P and Zwart, J, p. 34.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eric W. Weisstein (2005-10-26). "Spherical Coordinates". MathWorld. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SphericalCoordinates.html.

- ↑ "Video Game Math: Polar and Spherical Notation" (in en-AU). https://aie.edu/articles/video-game-math-polar-and-spherical-notation/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Line element (dl) in spherical coordinates derivation/diagram". Stack Exchange. October 21, 2011. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/74503.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Reed, Bruce Cameron (2019). Keplerian ellipses : the physics of the gravitational two-body problem. Morgan & Claypool Publishers, Institute of Physics. San Rafael [California] (40 Oak Drive, San Rafael, CA, 94903, US). ISBN 978-1-64327-470-6. OCLC 1104053368. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1104053368.

Bibliography

- Iyanaga, Shōkichi; Kawada, Yukiyosi (1977). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mathematics. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262090162.

- Morse PM, Feshbach H (1953). Methods of Theoretical Physics, Part I. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 658. ISBN 0-07-043316-X.

- Margenau H, Murphy GM (1956). The Mathematics of Physics and Chemistry. New York: D. van Nostrand. pp. 177–178. https://archive.org/details/mathematicsofphy0002marg.

- Korn GA, Korn TM (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 174–175. ASIN B0000CKZX7.

- Sauer R, Szabó I (1967). Mathematische Hilfsmittel des Ingenieurs. New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 95–96.

- Moon P, Spencer DE (1988). "Spherical Coordinates (r, θ, ψ)". Field Theory Handbook, Including Coordinate Systems, Differential Equations, and Their Solutions (corrected 2nd ed., 3rd print ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 24–27 (Table 1.05). ISBN 978-0-387-18430-2.

- Duffett-Smith P, Zwart J (2011). Practical Astronomy with your Calculator or Spreadsheet, 4th Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 34. ISBN 978-0521146548.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Spherical coordinates", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/s086660

- MathWorld description of spherical coordinates

- Coordinate Converter – converts between polar, Cartesian and spherical coordinates

fi:Koordinaatisto#Pallokoordinaatisto

|