Biology:Precambrian body plans

Until the late 1950s, the Precambrian was not believed to have hosted multicellular organisms. However, with radiometric dating techniques, it has been found that fossils initially found in the Ediacara Hills in Southern Australia date back to the late Precambrian. These fossils are body impressions of organisms shaped like disks, fronds and some with ribbon patterns that were most likely tentacles.

These are the earliest multicellular organisms in Earth's history, despite the fact that unicellularity had been around for a long time before that. The requirements for multicellularity were embedded in the genes of some of these cells, specifically choanoflagellates. These are thought to be the precursors for all animals. They are highly related to sponges (Porifera), which are the simplest multicellular animals.

In order to understand the transition to multicellularity during the Precambrian, it is important to look at the requirements for multicellularity—both biological and environmental.

Precambrian

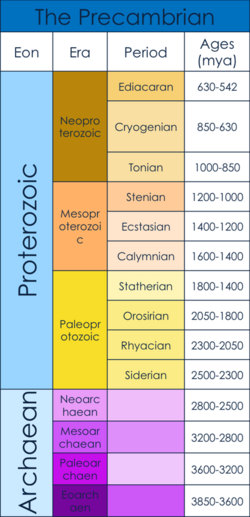

The Precambrian dates from the beginning of Earth's formation (4.6 billion years ago) to the beginning of the Cambrian Period, 539 million years ago.[1][2] The Precambrian consists of the Hadean, Archaean and Proterozoic eons.[1] Specifically, this article examines the Ediacaran, when the first multicellular bodies are believed to have arisen, as well as what caused the rise of multicellularity.[3] This time period arose after the Snowball Earth of the mid Neoproterozoic. The "Snowball Earth" was a period of worldwide glaciation, which is believed to have served as a population bottleneck for the subsequent evolution of multicellular organisms.[4]

Precambrian bodies

The Earth formed around 4.6 billion years ago, with unicellular life emerging somewhat later after the cessation of the Late Heavy Bombardment, a period of intense asteroid impacts possibly caused by migration of the gas giant planets to their current orbits, however multicellularity and bodies are a relatively recent event in Earth's history.[5] Bodies first started appearing towards the end of the Precambrian Era, during the Ediacaran period. The fossils of the Ediacaran period were first found in Southern Australia in the Ediacara Hills, hence the name. However these fossils were initially thought to be part of the Cambrian and it wasn't until the late 1950s when Martin Glaessner identified the fossils as actually being from the Precambrian era. The fossils that were found date to about 600 million years ago and are found in a variety of morphologies.[5]

Fossils of the Ediacaran

For more information, see Ediacaran biota.

The fossils found that date back to the Precambrian lack distinct structures since there were no skeletal forms during this period.[5] Skeletons did not arise until the Cambrian Period when oxygen levels increased. This is because skeletons require collagen, which uses Vitamin C as a cofactor, which requires oxygen.[6] For more information on the rise of oxygen see the section on oxygen. The majority of fossils from this Era come from either Mistaken Point on the East Coast of Canada or the Ediacara Hills in Southern Australia.[5]

Most of the fossils are found as impressions of soft-bodied organisms in the shape of disks, ribbons or fronds.[3][5] There are also trace fossils that provide evidence that some of these Precambrian organisms were most-likely worm-like creatures that were locomotive.[7] Most of these fossils lack any recognizable heads, mouths or digestive organs, and are thought to have fed via absorptive mechanisms and symbiotic relationships with chemoautotrophs (Chemotroph), photoautotrophs (Phototroph) or osmoautotrophs.[1] The ribbon-like fossils resemble tentacled organisms, and are thought to have fed by capturing prey. The frondose fossils resemble sea pens and other cnidarians. The trace fossils suggest that there were annelid type creatures, and the disk fossils resemble sponges. Despite these similarities, much of the identification is speculation since the fossils do not show very distinct structures. Other fossils do not resemble any known lineages.[1]

Many of the organisms, such as Charnia, found in Mistaken Point, were not like any organisms seen today. They had distinct bodies, however were lacking a head and digestive regions. Rather their body was organized in a very simple, fractal-like branching pattern.[8] Every element of the body was finely branched and grew by repetitive branching. This allowed the organism to have a large surface area and maximize nutrient absorption without needing a mouth and digestive system. However, there was minimal genetic information and therefore did not have the requirements that would have allowed them to evolve more efficient feeding techniques. This means they were probably outcompeted by other organisms, and thus became extinct.[8]

The organisms found in the Ediacaran Hills in Southern Australia displayed either radially symmetric body plans or, one organism, Spriggina, displayed the first bilateral symmetry. The Ediacaran Hills are thought to have once had a shallow reef where more light could penetrate the bottom of the ocean floor. This allowed for more diversity of organisms. The organisms found here resemble relatives of the cnidarians, mollusks or annelids.[8]

Charnia

Charnia fossils were originally found in the Charnwood Forest in England , hence named Charnia.[8] These fossils are from marine organisms that lived on the bottom of the ocean floor. The fossils have a fractal body plan and were frond shaped, meaning they resembled broad-leafed plants such as ferns. However they could not have been plants since they resided in the dark depths of the ocean floor. In Charnwood Forest, Charnia was found as an isolated species, however there were many more fossils found on the East Coast of Canada in Mistaken Point in Newfoundland. Charnia was attached to the bottom of the ocean floor, and was strongly current aligned. This is seen because there are disk-like shapes at the bottom of the Charnia fossil, which show where Charnia was tethered, and all the nearby fossils are facing the same direction. These fossils at Mistaken Point were preserved well under volcanic ash and layers of soft mud.[8] It has been determined via radiometric dating of the fossils that Charnia must have lived around 565 million years ago.[4][9]

Dickinsonia

Dickinsonia fossils are another notable fossil from the Ediacaran period, found in Southern Australia and Russia .[10] It remains unknown what type of organism Dickinsonia was; however, it has been considered a polychaete, turbellarian/annelid worm, jellyfish, polyp, protist, lichen or mushroom.[10] They were preserved in quartz sandstones, and date back to around 550 million years ago. Dickinsonia were soft-bodied organisms, that show some evidence of very slow movement.[4] There are faint, circular imprints in the rock which follow a path, and then following the same path there is a more definite circular imprint of the same size. This indicates that the organism probably moved slowly from one feeding area to the next and absorbed nutrients. It is speculated that the organism probably had very small appendages that allowed it to move much like starfish do today.[11]

Spriggina

Spriggina fossils represent the first known organisms with a bilaterally symmetric body plan. They had a head, tail and almost identical halves.[3] They probably had sensory organs in the head and digestive organs in the tail which would have allowed them to find food more efficiently. They were capable of locomotion, which gave them an advantage over other organisms from that era that were either tethered to the bottom of the ocean floor or moved very slowly. Spriggina was soft bodied, which leave the fossils as faint imprints. It is most likely related to annelids, however there is some speculation that it could be related to arthropods since it somewhat resembles trilobite fossils.[3][5]

Trace fossils

The Ediacaran fossils of Southern Australia contain trace fossils, which indicate that there were motile benthic organisms. The organisms that produced the traces in the sediments were all worm-like sediment feeders or detritus feeders (Detritivore). There are a few trace fossils, which resemble arthropod trails. Evidence suggests that arthropod-like organisms existed during the Precambrian. This evidence is in the type of trails left behind; specifically one specimen that shows six pairs of symmetrically placed impressions, which resemble trilobite walking trails.[7]

Transition from unicellularity to multicellularity

For the majority of Earth’s history life has been unicellular. However, unicellular organisms had the ingredients in them for multicellularity to arise. Despite having the ingredients for multicellularity, organisms were restricted due to the lack of hospitable environmental conditions. The rise of oxygen (The Great Oxygenation Event) led organisms to be able to develop more complex body plans. In order for multicellularity to have occurred, organisms must have been capable of cellular communication, aggregation, and specialized functions. The transition to multicellularity that began the evolution of animals from protozoa is one of the most poorly understood of history’s life events. Understanding choanoflagellates and their relation to sponges is important when positing theories on the origins of multicellularity[12]

Choanoflagellates

Choanoflagellates, also called "collar-flagellates" are unicellular protists that exist in both freshwaters and oceans.[13] Choanoflagellates have a spherical (or ovoid) cell body and a flagellum that is surrounded by a collar composed of actin microvilli.[13][14] The flagellum is used to facilitate movement and food intake. As the flagellum beats, it takes in water through the microvilli attached to the collar, which helps filter out unwanted bacteria and other tiny food particles.[13] Choanoflagellates are composed of approximately 150 species and reproduce by simple division.[15]

Choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta

(also known as Choanoflagellate Proterospongia)

The choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta is a rare freshwater eukaryote consisting of a number of cells embedded in a jelly-like matrix. This organism demonstrates a very primitive level of cell differentiation and specialization.[15] This is seen with flagellated cells and their collar structures that move the cell colony through the water, while the amoeboid cells on the inside serve to divide into new cells to assist in colony growth.

Similar low level cellular differentiation and specification can also be seen in sponges. They also have collar cells (also called choanocytes due to their similarities to choanoflaggellates) and amoeboid cells arranged in a gelatinous matrix. Unlike choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta, sponges also have other cell-types that can perform different functions (see sponges). Also, the collar cells of sponges beat within canals in the sponge body, whereas Salpingoeca rosetta’s collar cells reside on the inside and it lacks internal canals. Despite these minor differences, there is strong evidence that Proterospongia and Metazoa are highly related.[15]

Choanoflagellate Perplexa

These choanoflagellates are able to attach to one another via the pairing of collar microvilli.[16]

Choanoflagellate Codosiga Botrytis and Desmerella

These choanoflagellates are capable of forming colonies via fine intercellular bridges that allow the individual cells to attach. These bridges resemble ring canals that link developing spermatogonia or oogonia in animals.[16]

Sponges (Porifera)

Sponges are some of Earth’s oldest and most ubiquitous animals. The appearance of sponge spicule fossils date back to the Precambrian Era around 580 million years ago.[17] An assemblage of these fossils were found in the Doushanto formation in Southern China. Some circular impressions from the Ediacaran Hills in Southern Australia are also reported to be sponges. They are one of the only lineages of metazoans from this era that continue to survive, and remain relatively unchanged.[17][18] Sponges are such successful organisms due to their simple, yet effective morphology. They do not possess mouths or any digestive, nervous or circulatory systems. Instead they are filter feeders, which means that they obtain food through nutrients in the water.[19] They have pores, called ostia, that water travels through to a chamber called the spongocoel, and exits through a chamber called the osculum.[19] Through this water filtration system, they obtain nutrients that are needed for their survival. Specifically, they intracellularly digest bacteria, micro-algae or colloids.[20]

Sponge skeletons consist of either spongin or calcareous and siliceous spicules with some collagen molecules interspersed.[21] The collagen holds the sponge cells together. Different lineages of sponges are distinguished based on the composition of their skeletons. The three main classes of sponges are Demospongiae, Hexactinellid, and Calcareous.

Demonsponges are the most well-known type of sponge since they are used by humans. They are distinguished by a siliceous skeleton of two and four rayed spicules and contain the protein spongin.

Hexactinellid are also called glass sponges, and are distinguished by a six-rayed glass skeleton. These sponges are also capable of carrying out action potentials.

Calcareous sponges are characterized by a calcium carbonate skeleton and comprise less than 5% of sponges.[21]

Cells

Sponges have around 6 different types of cells that can perform different functions.[21] Sponges are a good model for studying the origin of multicellularity because the cells are capable of communicating with one another and re-aggregating. In an experiment conducted by Henry Van Peters Wilson in 1910, it was found that cells from dissociated sponges could send out signals and recognize each other to form a new individual.[22] This suggests that the cells that compose sponges are capable of independent living, however once multicellularity was possible then aggregating together to form one organism was a more efficient way of living.

The most notable cell types of sponges are the goblet-shaped cells called choanocytes, so named for their similarity to choanoflagellates.[21] The similarities between these two cells types makes scientists believe that choanoflagellates are the sister taxa to metazoa. The flagella of these cells are what drive the water movement through the sponge body.[23] The cell body of choanocytes is what is responsible for nutrient absorption. In some species these cells can develop into gametes.[21]

The Pinacocytes are the cells on the exterior of the sponge that line the cell body. They are tightly packed together and very thin.[21]

The mesenchyme lines the region between the pinacocytes and the choanocytes. They contain a matrix composed of proteins and spicules.[21]

Archaeocytes are special types of cells, in that they can transform into all of the other cell types. They will do what is needed in the sponge body, such as ingest and digest food, transport nutrients to other cells in the sponge body. These cells are also capable of developing into gametes in some sponge species.[21]

The sclerocytes are responsible for the secretion of spicules. In species of sponges that use spongin instead of calcaerous and silicaceous spicules, the sclerocytes are replaced by spongocytes, which secrete spongin skeletal fibres.[21]

The myocytes and porocytes are responsible for contraction of the sponge. These contractions are analogous to muscle contractions in other organisms, since sponges do not have muscles. They are responsible for regulating the water flow through the sponge.[21]

The formation of multicellularity

The formation of multicellularity was a pivotal point in the evolution of life on Earth. Shortly after multicellularity arose, there was an immense increase in the diversity of living organisms at the beginning of the Cambrian Era, called the Cambrian Explosion. Multicellularity is believed to have evolved multiple times on Earth because it was a beneficial life strategy for organisms.[24] For multicellularity to occur, cells need to be capable of self-replication, cell-cell adhesion and cell-cell communication. There also must have been available oxygen and selective pressures in the environment.

Theory of cellular division: S. Rosetta

Work by Fairclough, Dayel and King suggests that S. Rosetta can exist in either single-cellular form or in colonies of 4-50 cells, which arrange themselves in tight knit packs of spheres.[16] This was established by performing an experiment involving the introduction of prey bacterium Algoriphagus species to a sample of uni-celled S. Rosetta organism and monitored the activity for 12 hours. Results of this study demonstrated that cell colonies were formed through cell-division of the initial solitary S. Rosetta cell rather than by cell aggregation. Further studies to support the theory of cell-proliferation were done by introducing then removing the drug aphidicolin which serves to block cell-division. When the drug was introduced, cell division stopped and colony formation resulted through cell-cell aggregation. When the drug was removed, cell-division dominated once again.[16]

Building blocks for cell-adhesion

By looking at the genome of the Choanoflagellate, "Monosiga brevicollis", scientists have inferred that choanoflagellates play a key role in the development of multicellularity.[13] Nicole King has done work looking at the genome of Monisiga brevicollis, and has found key protein domains that are shared between metazoans and choanoflagellates. These domains play a role in cell signalling and adhesion processes in metazoans. The finding that choanoflagellates also have these genes is an incredible discovery because it was previously thought that only metazoans had genes responsible for cell-cell communication and aggregation. This suggests that these domains play a key role in the origins of multicellularity since it ties a unicellular organism (choanoflagellates) to multicellular organisms (metazoans). It shows that the components required for multicellularity were present in the common ancestor between metazoans and choanoflagellates.[13]

Cell signaling and cell communication

Neither sponges nor the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens appear to be equipped with neuron synapses, however they both possess several factors related to the same synaptic function.[25] Therefore, it is likely that central features involved in synaptic transmission arose early in metazoan evolution, most likely around the time that much of the life on Earth was transitioning to multicellularity. It was found that the Munc18/syntaxin 1 complex could be an important component for the production of the SNARE protein. The secretion of SNARE protein from synaptic vesicles is believed to be critical for neuronal communication. The Munc18/syntaxin 1 complex found in M. brevicollis is both structurally and functionally similar to the metazoan complex. This suggests that it constitutes an important step in the reaction pathway toward SNARE assembly. It is believed that the common ancestor of choanoflagellates and metazoans used this primordial secretion machinery as a precursor to synaptic communication. This mechanism would eventually be used for cell-cell communication in animals.[25]

Reasons for the development of multicellularity

Despite the fact that prokaryotic cells contained the building blocks required for multicellularity to arise, this transition did not occur for around 1500 million years after the origins of the first eukaryotic cell.[12] Scientists have proposed two major theories for the reason that multicellularity arose so late after the appearance of life on Earth.

Predation theory for multicellularity

This theory postulates that multicellularity arose as a means for prey to escape predation. Larger prey are less likely to be preyed upon, and larger predators are more likely to catch prey. Therefore it is likely that multicellularity arose when the first predators evolved. By assembling as a larger, multicelled organism, prey could escape the attempts of a predator.[12] Therefore multicellularity was selectively favoured over unicellularity. This can be seen in a simple experiment conducted by Boraas et al. (1998).[26] When a predatory protist, Ochromonas valencia, was introduced to a prey population of Chlorella vulgaris, it was seen that within less than 100 generations of the prey species a multicellular growth form of the alga became dominant. This is interesting because before the predator was introduced, the population of Chlorella vulgaris retained its unicellular growth form for thousands of generations. It is likely that it would have remained unicellular indefinitely if the selective pressure that was induced by the predators had not been introduced. After multiple generations with the predator, the algal species retained a growth form of 8-10 cells, which was large enough to avoid the predator, but small enough that each cell still had access to nutrients.[26] This predator-prey relationship provides a likely reason for why it was beneficial for organisms to be multicellular.

Rise in oxygen levels theory for multicellularity

Despite the fact that organisms had the potential to become multicellular it is likely that it was not actually possible until the late Neoproterozoic. This is because multicellularity requires oxygen, and before the late Neoproterozoic there was very limited oxygen availability.[12] After the melting of the “Snowball Earth” during the mid Neoproterozoic, nutrients that were trapped in the ice flooded the oceans.[8] Surviving bacteria flourished due to the increased nutrient levels. Among these microbes were cyanobacteria and other oxygen producing bacteria, which led to the massive rise in oxygen levels. The increased oxygen availability allowed it to be used by cells in order to manufacture collagen. Collagen is the key component for cell aggregation, It is a rope-like molecule that “ties” cells together. Oxygen is required for collagen synthesis because ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) is essential for this process to occur.[6] A key component in the ascorbic acid molecule is oxygen (chemical formula C6H8O6).[27] Therefore, it is evident that the rise in oxygen is a crucial step to the rise of multicellularity since it is essential for the synthesis of collagen.[8]

Building blocks found in both sponges and humans

Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals and is an essential molecule in the formation of bones, skin and other connective tissue. Different types of collagen have been found in all multicellular organisms, including sponges.

It has been found that sponges do have a gene sequence coding for collagen type IV which is a diagnostic feature of the basal lamina.[28]

It has also been found that 29 types of collagen have been found to exist in humans. This vast group can further be divided into several families according to their primary structures and supramolecular organization. Among the many types of collagens, only the fibrillar and the basement membrane (type IV) collagens have been found in the sponges and cnidarians, which are the two earliest branching metazoan lineages. Studies have focused on the origin of fibrillar collagen molecules. In Sponges, there exist three clades of fibrillar molecules, A, B and C. It is proposed that only the B clade fibrillar collagens preserved their characteristic modular structure from sponge to human.[29]

In mammals, the fibrillar collagens involved in the formation of cross-striated fibrils are types I–III, V, and XI. Type II and type XI collagens compose the fibrils present in cartilage. These can be distinguished from collagens located in non-cartilaginous tissues, which include type I, III, and V collagens.[29]

Protein

Additional research on sponge proteins found that of 42 sponge proteins that were analysed, all of them had homologous proteins that are found in humans. An identity score of 53% was given to the similarity among sponge and human proteins, compared to a score of 42% when the same sequence was compared to that of C. elegans.[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Valentine, J.W (1994). "Late Precambrian bilaterians: grades and clades.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91 (15): 6751–6757. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6751. PMID 8041693. Bibcode: 1994PNAS...91.6751V.

- ↑ "Stratigraphic Chart 2022". International Stratigraphic Commission. February 2022. https://stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2022-02.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Erwin, Douglas; Valentine, James; Jablonski, David (1997). "The Origin of Body Plans: Recent fossil finds and new insights into animal development are providing fresh perspectives on the riddle of the explosion of animals during the Early Cambrian". American Scientist 85: 126–137. http://www.americanscientist.org/issues/postComment.aspx?id=951&y=1999&no=2&page=7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Narbonne, Guy; Gehling, James (2003). "Life after snowball: The oldest complex Ediacaran fossils". Geology 31 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0027:lastoc>2.0.co;2. Bibcode: 2003Geo....31...27N. Archived from the original on 2004-10-31. https://web.archive.org/web/20041031202040/http://geol.queensu.ca/people/narbonne/LifeAfterSnowball1.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Glaessner, Martin (1959). "The Oldest Fossil Faunas of South Australia". Geologische Rundschau 47 (2): 522–531. doi:10.1007/bf01800671. Bibcode: 1959GeoRu..47..522G. http://download-v2.springer.com/static/pdf/845/art%253A10.1007%252FBF01800671.pdf?token2=exp=1428003666~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F845%2Fart%25253A10.1007%25252FBF01800671.pdf*~hmac=5a1968a0f2d83b49bc3e284c1e0daf488bd22ba1804621c9dad7378cc6fd5333.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Towe, Kenneth (1970). "Oxygen-Collagen Priority and the Early Metazoan FossilRecord". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 65 (4): 781–788. doi:10.1073/pnas.65.4.781. PMID 5266150. Bibcode: 1970PNAS...65..781T.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Glaessner, Martin (1969). "Trace fossils from the Precambrian and basal Cambrian". Lethaia 2 (4): 369–393. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1969.tb01258.x. http://journals2.scholarsportal.info.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/details/00241164/v02i0004/369_tfftpabc.xml&janrain=false&linkcolor=0074be.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Attenborough, David. "First Life". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xR-yMiyquG4&spfreload=10.

- ↑ Antcliffe, Jonathan; Brasier, Martin (2008). "Charnia at 50: Developmental Models for Ediacaran Fronds". Palaeontology 51 (1): 1475–4983. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00738.x. Bibcode: 2008Palgy..51...11A.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Retallack, Gregory (2007). "Growth, decay and burial compaction of Dickinsonia, an iconic Ediacaran fossil". Alcheringa 31 (3): 215–240. doi:10.1080/03115510701484705.

- ↑ Sperling, Erik; Vinther, Jakob (2010). "A placozoan affinity for Dickinsonia and the evolution of late Proterozoic metazoan feeding modes.". Evolution & Development 12 (2): 201–209. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00404.x. PMID 20433459.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 King, Nicole (September 2004). "The Unicellular Ancestry of Animal Development". Developmental Cell 7 (3): 313–325. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.010. PMID 15363407. http://sv.epfl.ch/files/content/sites/svnew2/files/shared/LSS%20Seminars/King_2004_DevCell.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 King, Nicole (2008). "The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans". Nature 451 (7180): 783–788. doi:10.1038/nature06617. PMID 18273011. Bibcode: 2008Natur.451..783K.

- ↑ King, Nicole; Carrol, Sean B. (September 10, 2001). "A receptor tyrosine kinase from choanoflagellates: Molecular insights into early animal evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (26): 15032–15037. doi:10.1073/pnas.261477698. PMID 11752452. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...9815032K.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Waggoner, Ben. "Introduction to the Choanoflagellata: Where it all began for the animals". Berkeley. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/protista/choanos.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Dayel, Mark; Alegado, Rosanna; Fairclough, Stephen; Levin, Tera; Nichols, Scott; McDonald, Kent; King, Nicole (September 2011). "Cell differentiation and morphogenesis in the colony-forming choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta". Developmental Biology 357 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.003. PMID 21699890.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Li, Chia-Wei; Chen, Jun-Yuan; Hua, Tzu-En (February 1998). "Precambrian sponges with cellular structures". Science 279 (5352): 879–882. doi:10.1126/science.279.5352.879. PMID 9452391. Bibcode: 1998Sci...279..879L.

- ↑ Gehling, James; Rigby, Keith (1996). "Long expected sponges from the Neoproterozoic Ediacara fauna of South Australia". Journal of Paleontology 70 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1017/S0022336000023283.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Collins, Allen G.; Waggoner, Ben. "Porifera: More on Morphology". Berkeley. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/porifera/poriferamm.html.

- ↑ Dupont, Samuel; Corre, Erwan; Li, Yanyan; Vacelet, Jean; Bourguet-Kondracki, Marie-Lise (December 2013). "First insights into the microbiome of a carnivorous sponge". FEMS Microbiology Ecology 86 (3): 520–531. doi:10.1111/1574-6941.12178. PMID 23845054.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 Collins, Allen G.. "Porifera: The Cells". Berkeley. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/porifera/pororg.html.

- ↑ Larroux, Claire (2006). "Developmental expression of transcription factor genes in a demosponge: insights into the origin of metazoan multicellularity". Evolution and Development 8 (2): 150–173. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142x.2006.00086.x. PMID 16509894.

- ↑ Myers, Phil. "Porifera Sponges". http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Porifera/.

- ↑ Iwasa, Janet; Szostak, Jack. "A Timeline of Life's Evolution". http://exploringorigins.org/timeline.html.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Buckhardt, Pawel (August 2, 2011). "Primordial neurosecretory apparatus identified in the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (37): 15264–15269. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106189108. PMID 21876177. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10815264B.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Boraas, Martin; Seale, Dianne; Boxhorn, Joseph (1998). "Phagotrophy by a flagellate selects for colonial prey: A possible origin of multicellularity". Evolutionary Ecology 12 (2): 153–164. doi:10.1023/A:1006527528063.

- ↑ Naidu, Akhilender (2003). "Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery ? An overview". Nutrition Journal 2 (7): 7. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-2-7. PMID 14498993.

- ↑ Tyler, Seth (2003). "Epithelium—the primary building block for metazoan complexity". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.55. PMID 21680409.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Exposito, Jean-Yves; Larroux, Claire; Cluzel, Caroline; Valcourt, Ulrich; Lethias, Claire; Degnan, Bernard (2008). "Demosponge and Sea Anemone Fibrillar Collagen Diversity Reveals the Early Emergence of A/C Clades and the Maintenance of the Modular Structure of Type V/XI Collagens from Sponge to Human". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (42): 28226–28235. doi:10.1074/jbc.M804573200. PMID 18697744.

- ↑ Gamulin, Vera; Muller, Isabel; Muller, Werner (2008). "Sponge proteins are more similar to those of Homo sapiens than to Caenorhabditis elegans.". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 71 (4): 821–828. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2000.tb01293.x.

|