Earth:Great Oxygenation Event

Stage 1 (3.85–2.45 Ga): Practically no O2 in the atmosphere. The oceans were also largely anoxic with the possible exception of O2 in the shallow oceans.

Stage 2 (2.45–1.85 Ga): O2 produced, rising to values of 0.02 and 0.04 atm, but absorbed in oceans and seabed rock.

Stage 3 (1.85–0.85 Ga): O2 starts to gas out of the oceans, but is absorbed by land surfaces. No significant change in terms of oxygen level.

Stages 4 and 5 (0.85–present): Other O2 reservoirs filled; gas accumulates in atmosphere.[1]

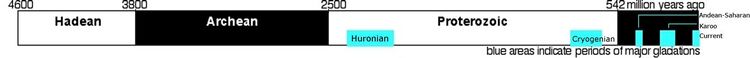

The Great Oxygenation Event, the beginning of which is commonly known in scientific media as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE, also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Crisis, Oxygen Holocaust,[2] Oxygen Revolution, or Great Oxidation) was the biologically induced appearance of dioxygen (O2) in Earth's atmosphere.[3] Geological, isotopic, and chemical evidence suggests that this major environmental change happened around 2.45 billion years ago (2.45 Ga),[4] during the Siderian period, at the beginning of the Proterozoic eon. The causes of the event remain unclear.[5] As of 2016[update], the geochemical and biomarker evidence for the development of oxygenic photosynthesis before the Great Oxidation Event has been mostly inconclusive.[6]

Oceanic cyanobacteria, which evolved into coordinated (but not multicellular or even colonial) macroscopic forms more than 2.3 billion years ago (approximately 200 million years before the GOE),[7] are believed[by whom?] to have become the first microbes to produce oxygen by photosynthesis.[8] Before the GOE, any free oxygen they produced was chemically captured by dissolved iron or by organic matter. The GOE started when oxygen produced by the cyanobacteria started escaping into the atmosphere, after other oxygen reservoirs were filled.

The increased production of oxygen set Earth's original atmosphere off-balance.[9] Free oxygen is toxic to obligate anaerobic organisms, and the rising concentrations may have destroyed most such organisms at the time.[10]

A spike in chromium contained in ancient rock-deposits formed underwater shows the accumulation had been washed off from the continental shelves. Chromium is not easily dissolved and its release from rocks would have required the presence of a powerful acid. One such acid, sulfuric acid (H2SO4), might have formed through bacterial reactions with pyrite.[11] Mats of oxygen-producing cyanobacteria can produce a thin layer, one or two millimeters thick, of oxygenated water in an otherwise anoxic environment even under thick ice; before oxygen started accumulating in the atmosphere, these organisms would already have adapted to oxygen.[12] Additionally, the free oxygen would have reacted with atmospheric methane, a greenhouse gas, greatly reducing its concentration and triggering the Huronian glaciation, possibly the longest episode of glaciation in Earth's history and called "snowball Earth".[13]

Eventually, the evolution of aerobic organisms that consumed oxygen established an equilibrium in its availability. Free oxygen has been an important constituent of the atmosphere ever since.[13]

Timing

The most widely accepted chronology of the Great Oxygenation Event suggests that free oxygen was first produced by prokaryotic and then later eukaryotic organisms that carried out photosynthesis more efficiently, producing oxygen as a waste product. The first oxygen-producing organisms arose long before the GOE,[14] perhaps as early as 3,400 million years ago.[15][16]

Initially, the oxygen they produced would have quickly been removed from the atmosphere by the chemical weathering of reducing (oxidizable) minerals, most notably iron. This 'mass rusting' led to the deposition of iron(III) oxide in the form of banded-iron formations such as the sediments in Minnesota and Pilbara, Western Australia. The saturation of these mineral sinks, and the resulting persistence of oxygen in the atmosphere, led within 50 million years to the start of the GOE.[17] Oxygen could have accumulated very rapidly: at today's rates of photosynthesis (much greater than those in the Precambrian without land plants), modern atmospheric O2 levels could be produced in only 2,000 years.[18]

Another hypothesis is that oxygen producers did not evolve until a few million years before the major rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration.[19] This is based on a particular interpretation of a supposed oxygen indicator used in previous studies, the mass-independent fractionation of sulfur isotopes. This hypothesis would eliminate the need to explain a lag in time between the evolution of oxyphotosynthetic microbes and the rise in free oxygen.

In either case, oxygen did eventually accumulate in the atmosphere, with two major consequences.

Firstly, it oxidized atmospheric methane (a strong greenhouse gas) to carbon dioxide (a weaker one) and water. This decreased the greenhouse effect of the Earth's atmosphere, causing planetary cooling, and triggered the Huronian glaciation. Starting around 2.4 billion years ago, this lasted 300-400 million years, and may have been the longest ever snowball Earth episode.[19][20]

Secondly, the increased oxygen concentrations provided a new opportunity for biological diversification, as well as tremendous changes in the nature of chemical interactions between rocks, sand, clay, and other geological substrates and the Earth's air, oceans, and other surface waters. Despite the natural recycling of organic matter, life had remained energetically limited until the widespread availability of oxygen. This breakthrough in metabolic evolution greatly increased the free energy available to living organisms, with global environmental impacts. For example, mitochondria evolved after the GOE, giving organisms the energy to exploit new, more complex morphologies interacting in increasingly complex ecosystems.[21]

Time lag theory

There may have been a gap of up to 900 million years between the start of photosynthetic oxygen production and the geologically rapid increase in atmospheric oxygen about 2.5–2.4 billion years ago. Several hypotheses propose to explain this time lag.

Tectonic trigger

The oxygen increase had to await tectonically driven changes in the Earth, including the appearance of shelf seas, where reduced organic carbon could reach the sediments and be buried.[22] The newly produced oxygen was first consumed in various chemical reactions in the oceans, primarily with iron. Evidence is found in older rocks that contain massive banded iron formations apparently laid down as this iron and oxygen first combined; most present-day iron ore lies in these deposits. Evidence suggests oxygen levels spiked each time smaller land masses collided to form a super-continent. Tectonic pressure thrust up mountain chains, which eroded to release nutrients into the ocean to feed photosynthetic cyanobacteria.[23]

Nickel famine

Early chemosynthetic organisms likely produced methane, an important trap for molecular oxygen, since methane readily oxidizes to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water in the presence of UV radiation. Modern methanogens require nickel as an enzyme cofactor. As the Earth's crust cooled and the supply of volcanic nickel dwindled, oxygen-producing algae began to out-perform methane producers, and the oxygen percentage of the atmosphere steadily increased.[24] From 2.7 to 2.4 billion years ago, the rate of deposition of nickel declined steadily from a level 400 times today's.[25]

Bistability

Another hypothesis posits a model of the atmosphere that exhibits bistability: two steady states of oxygen concentration. The state of stable low oxygen concentration (0.02%) experiences a high rate of methane oxidation. If some event raises oxygen levels beyond a moderate threshold, the formation of an ozone layer shields UV rays and decreases methane oxidation, raising oxygen further to a stable state of 21% or more. The Great Oxygenation Event can then be understood as a transition from the lower to the upper steady states.[26]

Hydrogen gas

Another theory credits the appearance of cyanobacteria with suppressing hydrogen gas and increasing oxygen.

Some bacteria in the early oceans could separate water into hydrogen and oxygen. Under the Sun's rays, hydrogen molecules were incorporated into organic compounds, with oxygen as a by-product. If the hydrogen-heavy compounds were buried, it would have allowed oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere.

However, in 2001 scientists realized that the hydrogen would instead escape into space through a process called methane photolysis, in which methane releases its hydrogen in a reaction with oxygen. This could explain why the early Earth stayed warm enough to sustain oxygen-producing lifeforms.[27]

Late evolution of oxy-photosynthesis theory

The oxygen indicator might have been misinterpreted. During the proposed lag era in the previous theory, there was a change in sediments from mass-independently fractionated (MIF) sulfur to mass-dependently fractionated (MDF) sulfur. This was assumed to show the appearance of oxygen in the atmosphere, since oxygen would have prevented the photolysis of sulfur dioxide, which causes MIF. However, the change from MIF to MDF of sulfur isotopes may instead have been caused by an increase in glacial weathering, or the homogenization of the marine sulfur pool as a result of an increased thermal gradient during the Huronian glaciation period (which in this interpretation was not caused by oxygenation).[19]

Role in mineral diversification

The Great Oxygenation Event triggered an explosive growth in the diversity of minerals, with many elements occurring in one or more oxidized forms near the Earth's surface.[28] It is estimated that the GOE was directly responsible for more than 2,500 of the total of about 4,500 minerals found on Earth today. Most of these new minerals were formed as hydrated and oxidized forms due to dynamic mantle and crust processes.[29] Script error: No such module "Simple horizontal timeline".

Origin of eukaryotes

It has been proposed that a local rise in oxygen levels due to cyanobacterial photosynthesis in ancient microenvironments was highly toxic to the surrounding biota, and that this selective pressure drove the evolutionary transformation of an archaeal lineage into the first eukaryotes.[30] Oxidative stress involving production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) might have acted in synergy with other environmental stresses (such as ultraviolet radiation and/or desiccation) to drive selection in an early archaeal lineage towards eukaryosis. This archaeal ancestor may already have had DNA repair mechanisms based on DNA pairing and recombination and possibly some kind of cell fusion mechanism.[31][32] The detrimental effects of internal ROS (produced by endosymbiont proto-mitochondria) on the archaeal genome could have promoted the evolution of meiotic sex from these humble beginnings.[31] Selective pressure for efficient DNA repair of oxidative DNA damages may have driven the evolution of eukaryotic sex involving such features as cell-cell fusions, cytoskeleton-mediated chromosome movements and emergence of the nuclear membrane.[30] Thus the evolution of eukaryotic sex and eukaryogenesis were likely inseparable processes that evolved in large part to facilitate DNA repair.[30][33] Constant pressure of endogenous ROS has been proposed to explain the ubiquitous maintenance of meiotic sex in eukaryotes.[31]

See also

- Geological history of oxygen

- Iodide

- Medea hypothesis

- Pasteur point

- Rare Earth hypothesis

- Stromatolite

References

- ↑ Holland, Heinrich D. "The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences. Vol. 361. 2006. pp. 903–915.

- ↑ Margulis, Lynn; Sagan, Dorion (1986). "Chapter 6, "The Oxygen Holocaust"". Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Microbial Evolution. California: University of California Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780520210646. https://books.google.com/books?id=eo_sMMRxgAUC&lpg=PA99&ots=oWKooBsh1G&dq=oxygen%20holocaust&pg=PA99#v=onepage&q=oxygen%20holocaust&f=false.

- ↑ Sosa Torres, Martha E.; Saucedo-Vázquez, Juan P.; Kroneck, Peter M.H. (2015). "Chapter 1, Section 2 "The rise of dioxygen in the atmosphere"". in Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres. Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 15. Springer. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_1.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (3 October 2013). "Earth's Oxygen: A Mystery Easy to Take for Granted". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/03/science/earths-oxygen-a-mystery-easy-to-take-for-granted.html. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ "University of Zurich. "Great Oxidation Event: More oxygen through multicellularity". ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 January 2013.". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/01/130117084856.htm.

- ↑ Planavsky, Noah J. (24 January 2014). "Evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis half a billion years before the Great Oxidation Event". Nature 7: 283–286. doi:10.1038/ngeo2122. Bibcode: 2014NatGe...7..283P. http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v7/n4/full/ngeo2122.html. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Flannery, D. T.; R.M. Walter (2012). "Archean tufted microbial mats and the Great Oxidation Event: new insights into an ancient problem". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 59 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/08120099.2011.607849. Bibcode: 2012AuJES..59....1F.

- ↑ "The Rise of Oxygen - Astrobiology Magazine" (in en-US). http://www.astrobio.net/news-exclusive/the-rise-of-oxygen/.

- ↑ "University of Zurich. "Great Oxidation Event: More oxygen through multicellularity." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 January 2013". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/01/130117084856.htm.

- ↑ Hentges, David J. (1996), Baron, Samuel, ed., "Anaerobes: General Characteristics", Medical Microbiology (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston), ISBN 0963117211, PMID 21413255, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7638/, retrieved 2018-07-07

- ↑ "Evidence of Earliest Oxygen-Breathing Life on Land Discovered". http://www.livescience.com/16714-oxygen-breathing-life-chromium.html.

- ↑ Oxygen oasis in Antarctic lake reflects Earth in distant past

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Frei, R.; Gaucher, C.; Poulton, S. W.; Canfield, D. E. (2009). "Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes". Nature 461 (7261): 250–253. doi:10.1038/nature08266. PMID 19741707. Bibcode: 2009Natur.461..250F. Lay summary.

- ↑ Dutkiewicz, A.; Volk, H.; George, S. C.; Ridley, J.; Buick, R. (2006). "Biomarkers from Huronian oil-bearing fluid inclusions: an uncontaminated record of life before the Great Oxidation Event". Geology 34 (6): 437. doi:10.1130/G22360.1. Bibcode: 2006Geo....34..437D.

- ↑ Caredona, Tanai (6 March 2018). "Early Archean origin of heterodimeric Photosystem I". Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00548. https://www.heliyon.com/article/e00548. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Howard, Victoria (7 March 2018). "Photosynthesis Originated A Billion Years Earlier Than We Thought, Study Shows.". Astrobiology Magazine. https://www.astrobio.net/also-in-news/photosynthesis-originated-billion-years-earlier-thought-study-shows/. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Anbar, A.; Duan, Y.; Lyons, T.; Arnold, G.; Kendall, B.; Creaser, R.; Kaufman, A.; Gordon, G. et al. (2007). "A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event?". Science 317 (5846): 1903–1906. doi:10.1126/science.1140325. PMID 17901330. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317.1903A.

- ↑ Dole, M. (1965). "The Natural History of Oxygen". The Journal of General Physiology 49 (1): Suppl:Supp5–27. doi:10.1085/jgp.49.1.5. PMID 5859927.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Robert E. Kopp; Joseph L. Kirschvink; Isaac A. Hilburn; Cody Z. Nash (2005). "The Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth: A climate disaster triggered by the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (32): 11131–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504878102. PMID 16061801. PMC 1183582. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10211131K. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/0504878102v1.

- ↑ First breath: Earth's billion-year struggle for oxygen New Scientist, #2746, 5 February 2010 by Nick Lane.

- ↑ Sperling, Erik; Frieder, Christina; Raman, Akkur; Girguis, Peter; Levin, Lisa; Knoll, Andrew (Aug 2013). "Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 13446–13451. doi:10.1073/pnas.1312778110. PMID 23898193. PMC 3746845. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..11013446S. http://www.pnas.org/content/110/33/13446.full. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ↑ Lenton, T. M.; H. J. Schellnhuber; E. Szathmáry (2004). "Climbing the co-evolution ladder". Nature 431 (7011): 913. doi:10.1038/431913a. PMID 15496901. Bibcode: 2004Natur.431..913L.

- ↑ American, Scientific. "Abundant Oxygen Indirectly Due to Tectonics". http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/5C271294-EE45-D925-BEBBEF03016A7CF4/.

- ↑ American, Scientific. "Breathing Easy Thanks to the Great Oxidation Event". http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/breathing-easy-thanks-to-great-oxid-09-04-13/.

- ↑ Kurt O. Konhauser (2009). "Oceanic nickel depletion and a methanogen famine before the Great Oxidation Event". Nature 458 (7239): 750–753. doi:10.1038/nature07858. PMID 19360085. Bibcode: 2009Natur.458..750K.

- ↑ Goldblatt, C.; T.M. Lenton; A.J. Watson (2006). "The Great Oxidation at 2.4 Ga as a bistability in atmospheric oxygen due to UV shielding by ozone". Geophysical Research Abstracts 8: 00770. http://www.cosis.net/abstracts/EGU06/00770/EGU06-J-00770.pdf.

- ↑ Franzen, Harald. "New Theory Explains How Earth's Early Atmosphere Became Oxygen-Rich". http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/new-theory-explains-how-e/.

- ↑ Sverjensky, Dimitri A.; Lee, Namhey (2010-02-01). "The Great Oxidation Event and Mineral Diversification" (in en). Elements 6 (1): 31–36. doi:10.2113/gselements.6.1.31. ISSN 1811-5209. http://elements.geoscienceworld.org/content/6/1/31.

- ↑ "Evolution of Minerals", Scientific American, March 2010

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "Uniting sex and eukaryote origins in an emerging oxygenic world". Biol. Direct 5: 53. August 2010. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-5-53. PMID 20731852.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "How oxygen gave rise to eukaryotic sex". Proc. Biol. Sci. 285 (1872). February 2018. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2706. PMID 29436502.

- ↑ Bernstein H, Bernstein C. Sexual communication in archaea, the precursor to meiosis. pp. 103-117 in Biocommunication of Archaea (Guenther Witzany, ed.) 2017. Springer International Publishing ISBN 978-3-319-65535-2 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-65536-9

- ↑ Bernstein, H., Bernstein, C. Evolutionary origin and adaptive function of meiosis. In “Meiosis”, Intech Publ (Carol Bernstein and Harris Bernstein editors), Chapter 3: 41-75 (2013).

External links

- First breath: Earth's billion-year struggle for oxygen New Scientist, #2746, 5 February 2010 by Nick Lane. [1]