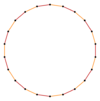

Icosidigon

| Regular icosidigon | |

|---|---|

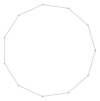

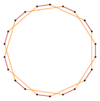

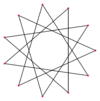

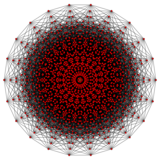

A regular icosidigon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 22 |

| Schläfli symbol | {22}, t{11} |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D22), order 2×22 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | ≈163.636° |

| Dual polygon | Self |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

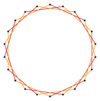

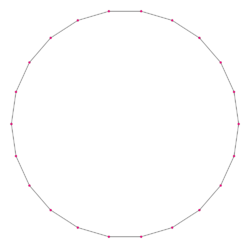

In geometry, an icosidigon (or icosikaidigon) or 22-gon is a twenty-two-sided polygon. The sum of any icosidigon's interior angles is 3600 degrees.

Regular icosidigon

The regular icosidigon is represented by Schläfli symbol {22} and can also be constructed as a truncated hendecagon, t{11}.

The area of a regular icosidigon is: (with t = edge length)

- [math]\displaystyle{ A = 5.5t^2 \cot \frac{\pi}{22}. }[/math]

Construction

As 22 = 2 × 11, the icosidigon can be constructed by truncating a regular hendecagon. However, the icosidigon is not constructible with a compass and straightedge, since 11 is not a Fermat prime. Consequently, the icosidigon cannot be constructed even with an angle trisector, because 11 is not a Pierpont prime. It can, however, be constructed with the neusis method.

Symmetry

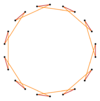

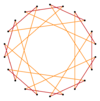

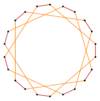

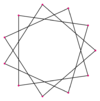

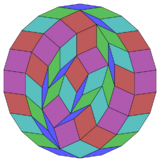

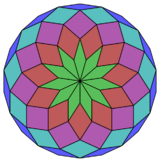

The regular icosidigon has Dih22 symmetry, order 44. There are 3 subgroup dihedral symmetries: Dih11, Dih2, and Dih1, and 4 cyclic group symmetries: Z22, Z11, Z2, and Z1.

These 8 symmetries can be seen in 10 distinct symmetries on the icosidigon, a larger number because the lines of reflections can either pass through vertices or edges. John Conway labels these by a letter and group order.[1] The full symmetry of the regular form is r44 and no symmetry is labeled a1. The dihedral symmetries are divided depending on whether they pass through vertices (d for diagonal) or edges (p for perpendiculars), and i when reflection lines path through both edges and vertices. Cyclic symmetries n are labeled as g for their central gyration orders.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g22 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can seen as directed edges.

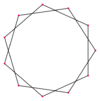

The highest symmetry irregular icosidigons are d22, an isogonal icosidigon constructed by eleven mirrors which can alternate long and short edges, and p22, an isotoxal icosidigon, constructed with equal edge lengths, but vertices alternating two different internal angles. These two forms are duals of each other and have half the symmetry order of the regular icosidigon.

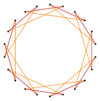

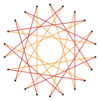

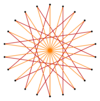

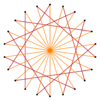

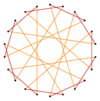

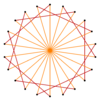

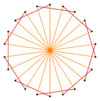

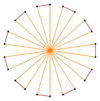

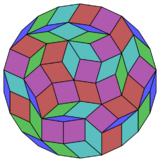

Dissection

Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into m(m-1)/2 parallelograms. In particular this is true for regular polygons with evenly many sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. For the regular icosidigon, m=11, and it can be divided into 55: 5 sets of 11 rhombs. This decomposition is based on a Petrie polygon projection of a 11-cube.[2]

11-cube |

|

|

|

|

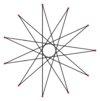

Related polygons

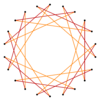

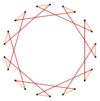

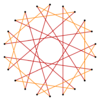

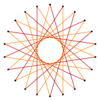

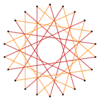

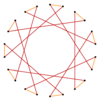

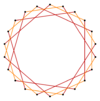

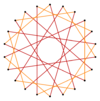

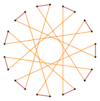

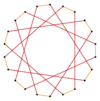

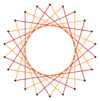

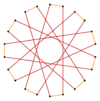

An icosidigram is a 22-sided star polygon. There are 4 regular forms given by Schläfli symbols: {22/3}, {22/5}, {22/7}, and {22/9}. There are also 7 regular star figures using the same vertex arrangement: 2{11}, 11{2}.

There are also isogonal icosidigrams constructed as deeper truncations of the regular hendecagon {11} and hendecagrams {11/2}, {11/3}, {11/4} and {11/5}.[3]

References

- ↑ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275-278)

- ↑ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ↑ The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugène Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and its History, (1994), Metamorphoses of polygons, Branko Grünbaum