Biology:Haplogroup L3 (mtDNA)

| Haplogroup L3 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 80,000–60,000 BP,[1] 70,000 BP[2] |

| Possible place of origin | East Africa[3][4][5][2] or Asia[6] |

| Ancestor | L3'4 |

| Descendants | L3a, L3b'f, L3c'd, L3e'i'k'x, L3h, M, N |

| Defining mutations | 769, 1018, 16311[7] |

Haplogroup L3 is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup. The clade has played a pivotal role in the early dispersal of anatomically modern humans.

It is strongly associated with the out-of-Africa migration of modern humans of about 70–50,000 years ago. It is inherited by all modern non-African populations, as well as by some populations in Africa.[8][3]

Origin

Haplogroup L3 arose close to 70,000 years ago, near the time of the recent out-of-Africa event. This dispersal originated in East Africa and expanded to West Asia, and further to South and Southeast Asia in the course of a few millennia, and some research suggests that L3 participated in this migration out of Africa. L3 is also common amongst African Americans and Afro-Brazilians. A 2007 estimate for the age of L3 suggested a range of 104–84,000 years ago.[9] More recent analyses, including Soares et al. (2012) arrive at a more recent date, of roughly 70–60,000 years ago. Soares et al. also suggest that L3 most likely expanded from East Africa into Eurasia sometime around 65–55,000 years ago years ago as part of the recent out-of-Africa event, as well as from East Africa into Central Africa from 60 to 35,000 years ago.[3] In 2016, Soares et al. again suggested that haplogroup L3 emerged in East Africa, leading to the Out-of-Africa migration, around 70–60,000 years ago.[10]

Haplogroups L6 and L4 form sister clades of L3 which arose in East Africa at roughly the same time but which did not participate in the out-of-Africa migration. The ancestral clade L3'4'6 has been estimated at 110 kya, and the L3'4 clade at 95 kya.[8]

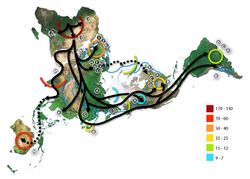

a: Exit of the L3 precursor to Eurasia. b: Return to Africa and expansion to Asia of basal L3 lineages with subsequent differentiation in both continents.

The possibility of an origin of L3 in Asia was also proposed by Cabrera et al. (2018) based on the similar coalescence dates of L3 and its Eurasian-distributed M and N derivative clades (ca. 70 kya), the distant location in Southeast Asia of the oldest known subclades of M and N, and the comparable age of the paternal haplogroup DE. According to this hypothesis, after an initial out-of-Africa migration of bearers of pre-L3 (L3'4*) around 125 kya, there would have been a back-migration of females carrying L3 from Eurasia to East Africa sometime after 70 kya. The hypothesis suggests that this back-migration is aligned with bearers of paternal haplogroup E, which it also proposes to have originated in Eurasia. These new Eurasian lineages are then suggested to have largely replaced the old autochthonous male and female North-East African lineages.[6]

According to other research, though earlier migrations out of Africa of anatomically modern humans occurred, current Eurasian populations descend instead from a later migration from Africa dated between about 65,000 and 50,000 years ago (associated with the migration out of L3).[11][4][12]

Vai et al. (2019) suggest, from a newly discovered old and deeply-rooted branch of maternal haplogroup N found in early Neolithic North African remains, that haplogroup L3 originated in East Africa between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago, and both spread within Africa and left Africa as part of the Out-of-Africa migration, with haplogroup N diverging from it soon after (between 65,000 and 50,000 years ago) either in Arabia or possibly North Africa, and haplogroup M originating in the Middle East around the same time as N.[4]

A study by Lipson et al. (2019) analyzing remains from the Cameroonian site of Shum Laka found them to be more similar to modern-day Pygmy peoples than to West Africans, and suggests that several other groups (including the ancestors of West Africans, East Africans and the ancestors of non-Africans) commonly derived from a human population originating in East Africa between about 80,000-60,000 years ago, which they suggest was also the source and origin zone of haplogroup L3 around 70,000 years ago.[13]

Distribution

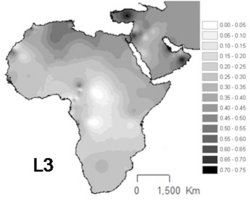

L3 is common in Northeast Africa and some other parts of East Africa,[14] in contrast to others parts of Africa where the haplogroups L1 and L2 represent around two thirds of mtDNA lineages.[15] L3 sublineages are also frequent in the Arabian peninsula.

L3 is subdivided into several clades, two of which spawned the macrohaplogroups M and N that are today carried by most people outside Africa.[15] There is at least one relatively deep non-M, non-N clade of L3 outside Africa, L3f1b6, which is found at a frequency of 1% in Asturias, Spain. It diverged from African L3 lineages at least 10,000 years ago.[16]

According to Maca-Meyer et al. (2001), "L3 is more related to Eurasian haplogroups than to the most divergent African clusters L1 and L2".[17] L3 is the haplogroup from which all modern humans outside Africa derive.[18] However, there is a greater diversity of major L3 branches within Africa than outside of it, the two major non-African branches being the L3 offshoots M and N.

Subclade distribution

L3 has seven equidistant descendants: L3a, L3b'f, L3c'd, L3e'i'k'x, L3h, M, N. Five are African, while two are associated with the Out of Africa event.

- N – Eurasia possibly due to migration from Africa, and North Africa possibly due to back-migration from Eurasia.[3][6][4]

- M – Asia, the Mediterranean Basin, and parts of Africa due to back-migration.[3][6]

- L3a – East Africa.[8][3] Moderate to high frequencies found among the Sanye, Samburu, Iraqw, Yaaku, El-Molo and other minor indigenous populations from the East African Rift Valley. It is infrequent to nonexistent in Sudan and the Sahel zone.[19]

- L3b'f

- L3b – Spread from East Africa in the upper paleolithic to West-Central Africa. Some subclades spread from Central Africa to East Africa with the Bantu migration.[3]

- L3f – Northeast Africa, Sahel, Arabian peninsula, Iberia. Gaalien,[22] Beja[22]

- L3f1

- L3f1a – Carried by migrants from Eastern Africa into the Sahel and Central Africa.[3]

- L3f1b – Carried by migrants from Eastern Africa into the Sahel and Central Africa.[3]

- L3f1b1 – Carried from Central Africa into Southern and Eastern Africa with the Bantu migration.[3]

- L3f1b1a – Settled from East-Central Africa to Central-West Africa and into North Africa and Berber regions.[3]

- L3f1b4 – Carried from Central Africa into Southern and Eastern Africa with the Bantu migration.[3]

- L3f1b1 – Carried from Central Africa into Southern and Eastern Africa with the Bantu migration.[3]

- L3f1b6 – Rare, found in Iberia.[16]

- L3f2 – Primarily distributed in East Africa.[3] Also found in North Africa and Central Africa.[21]

- L3f3 – Spread from Eastern Africa to Chad and the Sahel around 8–9 ka.[3] Found in the Chad Basin.[21][23]

- L3f1

- L3c'd

- L3c – Extremely rare lineage with only two samples found so far in Eastern Africa and the Near East.[3]

- L3d – Spread from East Africa in the upper paleolithic to Central Africa. Some subclades spread to East Africa with the Bantu migration.[3] Found among the Fulani,[8] Chadians,[8] Ethiopians,[24] Akan people,[25] Mozambique,[24] Yemenites,[24] Egyptians, Berbers[26]

- L3e'i'k'x

- L3e – Suggested to have originated in the Central Africa/Sudan region about 45,000 years ago during the upper paleolithic period.[27] It is the most common L3 sub-clade in Bantu-speaking populations.[28] L3e is also the most common L3 subclade amongst African Americans and Afro-Brazilians.[29]

- L3e1 – Spread from West-Central Africa to Southwest Africa with the Bantu migration. Found in Angola (6.8%).[30] Mozambique, Sudanese and Kikuyu of Kenya, as well as in Yemen, the Tikar of Cameroon,[31] and among the Akan people of Ghana.[25]

- L3e5 – Originated in the Chad Basin. Found in Algeria,[32] as well as Burkina Faso, Nigeria, South Tunisia, South Morocco and Egypt[33]

- L3i Almost exclusively found in East Africa.[3]

- L3k – Rare haplogroup primarily found in North Africa and the Sahel.[3][21]

- L3x – Almost exclusively found in East Africa.[3] Found among Ethiopian Oromos,[24] Egyptians[Note 1][34]

- L3e – Suggested to have originated in the Central Africa/Sudan region about 45,000 years ago during the upper paleolithic period.[27] It is the most common L3 sub-clade in Bantu-speaking populations.[28] L3e is also the most common L3 subclade amongst African Americans and Afro-Brazilians.[29]

- L3h – Almost exclusively found in East Africa.[3]

- L3h1 – Primarily found in East Africa with branches of L3h1b1 sporadically found in the Sahel and North Africa.[20][21]

- L3h2 – Found in Northeast Africa and Socotra. Split from other L3h branches as early as 65–69 ka during the middle paleolithic.[20][21]

Ancient and historic samples

Haplogroup L3 has been observed in an ancient fossil belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B culture.[35] L3x2a was observed in a 4,500 year old hunter-gather excavated in Mota, Ethiopia, with the ancient fossil found to be most closely related to modern Southwest Ethiopian populations.[36][37] Haplogroup L3 has also been found among ancient Egyptian mummies (1/90; 1%) excavated at the Abusir el-Meleq archaeological site in Middle Egypt, with the rest deriving from Eurasian subclades, which date from the Pre-Ptolemaic/late New Kingdom and Ptolemaic periods. The Ancient Egyptian mummies bore Near eastern genomic component most closely related to modern near easterners.[38] Additionally, haplogroup L3 has been observed in ancient Guanche fossils excavated in Gran Canaria and Tenerife on the Canary Islands, which have been radiocarbon-dated to between the 7th and 11th centuries CE. All of the clade-bearing individuals were inhumed at the Gran Canaria site, with most of these specimens found to belong to the L3b1a subclade (3/4; 75%) with the rest from both islands (8/11; 72%) deriving from Eurasian subclades. The Guanche skeletons also bore an autochthonous Maghrebi genomic component that peaks among modern Berbers, which suggests that they originated from ancestral Berber populations inhabiting northwestern Affoundnat a high ncy[39]

A variety of L3 have been uncovered in ancient remains associated with the Pastoral Neolithic and Pastoral Iron Age of East Africa.[40]

| Culture | Genetic cluster or affinity | Country | Site | Date | Maternal Haplogroup | Paternal Haplogroup | Source |

| Early pastoral | PN | Kenya | Prettejohn's Gully (GsJi11) | 4060–3860 | L3f1b | – | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Kenya | Cole's Burial (GrJj5a) | 3350–3180 | L3i2 | E-V32 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic or Elmenteitan | PN | Kenya | Rigo Cave (GrJh3) | 2710–2380 | L3f | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Kenya | Naishi Rockshelter | 2750–2500 | L3x1a | E-V1515 (prob. E-M293) | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Tanzania | Gishimangeda Cave | 2490–2350 | L3x1 | – | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Kenya | Naivasha Burial Site | 2350–2210 | L3h1a1 | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Kenya | Naivasha Burial Site | 2320–2150 | L3x1a | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Tanzania | Gishimangeda Cave | 2150–2020 | L3i2 | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic or Elmenteitan | PN | Kenya | Njoro River Cave II | 2110–1930 | L3h1a2a1 | – | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | N/A | Tanzania | Gishimangeda Cave | 2000–1900 | L3h1a2a1 | – | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Neolithic | PN | Kenya | Ol Kalou | 1810–1620 | L3d1d | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Iron Age | PIA | Kenya | Kisima Farm, C4 | 1060–940 | L3h1a1 | E-M75 (excl. M98) | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Iron Age | PIA | Kenya | Emurua Ole Polos (GvJh122) | 420–160 | L3h1a1 | E-M293 | Prendergast 2019 |

| Pastoral Iron Age | PN outlier | Kenya | Kokurmatakore | N/A | L3a2a | E-M35 (not E-M293) | Prendergast 2019 |

Tree

This phylogenetic tree of haplogroup L3 subclades is based on the paper by Mannis van Oven and Manfred Kayser Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation[7] and subsequent published research.[41]

Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA)

- L1-6

- L2-6

- L2'3'4'6

- L3'4'6

- L3'4

- L3

- L3a

- L3a1

- L3a1a

- L3a1b

- L3a2

- L3a2a

- L3a1

- L3b'f

- L3b

- L3b1

- L3b1a

- L3b1a1

- L3b1a2

- L3b1a3

- L3b1a4

- L3b1a5

- L3b1a5a

- L3b1a6

- L3b1a7

- L3b1a7

- L3b1a8

- L3b1a9

- L3b1a9a

- L3b1a10

- L3b1a11

- L3b1b

- L3b1b1

- L3b1a

- L3b2

- L3b2a

- L3b2a

- L3b3

- L3b1

- L3f

- L3f1

- L3f1a

- L3f1a1

- L3f1b

- L3f1b1

- L3f1b2

- L3f1b2a

- L3f1b3

- L3f1b4

- L3f1b4a

- L3f1b4a1

- L3f1b4b

- L3f1b4c

- L3f1b4a

- L3f1b5

- L3f1a

- L3f2

- L3f2a

- L3f2b

- L3f3

- L3f3a

- L3f3b

- L3f1

- L3b

- L3c'd

- L3c

- L3d

- L3d1-5

- L3d1

- L3d1a

- L3d1a1

- L3d1a1a

- L3d1a1

- L3d1b

- L3d1b1

- L3d1c

- L3d1d

- L3d1a

- 199

- L3d2

- L3d5

- L3d3

- L3d3a

- L3d4

- L3d5

- L3d1

- L3d1-5

- L3e'i'k'x

- L3e

- L3e1

- L3e1a

- L3e1a1

- L3e1a1a

- 152

- L3e1a2

- L3e1a3

- L3e1a1

- L3e1b

- L3e1c

- L3e1d

- L3e1e

- L3e1a

- L3e2

- L3e2a

- L3e2a1

- L3e2a1a

- L3e2a1b

- L3e2a1b1

- L3e2a1

- L3e2b

- L3e2b1

- L3e2b1a

- L3e2b2

- L3e2b3

- L3e2b1

- L3e2a

- L3e3'4'5

- L3e3'4

- L3e3

- L3e3a

- L3e3b

- L3e3b1

- L3e4

- L3e3

- L3e5

- L3e3'4

- L3e1

- L3i

- L3i1

- L3i1a

- L3i1b

- L3i2

- L3i1

- L3k

- L3k1

- L3x

- L3x1

- L3x1a

- L3x1a1

- L3x1a2

- L3x1b

- L3x1a

- L3x2

- L3x2a

- L3x2a1

- L3x2a1a

- L3x2a1

- L3x2b

- L3x2a

- L3x1

- L3e

- L3h

- L3h1

- L3h1a

- L3h1a1

- L3h1a2

- L3h1a2a

- L3h1a2b

- L3h1b

- L3h1b1

- L3h1b1a

- L3h1b1a1

- L3h1b1a

- L3h1b2

- L3h1b1

- L3h1a

- L3h2

- L3h1

- M

- N

- L3a

- L3

- L3'4

- L3'4'6

- L2'3'4'6

- L2-6

See also

|

Phylogenetic tree of human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial Eve (L) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L0 | L1–6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CZ | D | E | G | Q | O | A | S | R | I | W | X | Y | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | Z | B | F | R0 | pre-JT | P | U | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HV | JT | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | V | J | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Soares et al. 2011. Point estimates of 71.6 kya by Soares et al. (2009) and of 70.2 by Fernandes et al. (2015).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lipson, Mark (22 January 2020). "Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history". Nature 577 (7792): 665–669. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1929-1. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 8545173694. PMID 31969706. Bibcode: 2020Natur.577..665L.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 Soares, P.; Alshamali, F.; Pereira, J. B.; Fernandes, V.; Silva, N. M.; Afonso, C.; Costa, M. D.; Musilova, E. et al. (2011-11-16). "The Expansion of mtDNA Haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa" (in en). Molecular Biology and Evolution 29 (3): 915–927. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr245. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 22096215.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Sci Rep 9 (1): 3530. March 2019. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39802-1. PMID 30837540. Bibcode: 2019NatSR...9.3530V.

- ↑ Osman, Maha M.. "Mitochondrial HVRI and whole mitogenome sequence variations portray similar scenarios on the genetic structure and ancestry of northeast Africans". Meta Gene. http://81.95.108.158/return-files/Mitochondrial%20HVRI.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology 18 (1): 98. June 2018. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMID 29921229.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Van Oven, Mannis; Kayser, Manfred (2009). "Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation". Human Mutation 30 (2): E386–94. doi:10.1002/humu.20921. PMID 18853457.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Behar, Doron M.; Villems, Richard; Soodyall, Himla; Blue-Smith, Jason; Pereira, Luisa; Metspalu, Ene; Scozzari, Rosaria; Makkan, Heeran et al. (2008). "The Dawn of Human Matrilineal Diversity". The American Journal of Human Genetics 82 (5): 1130–40. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.002. PMID 18439549. PMC 2427203. http://public-files.prbb.org/publicacions/84a384f0-834c-012c-a7dc-000c293b26d5.pdf.

- ↑ Gonder, M. K.; Mortensen, H. M.; Reed, F. A.; De Sousa, A.; Tishkoff, S. A. (2006). "Whole-mtDNA Genome Sequence Analysis of Ancient African Lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (3): 757–68. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl209. PMID 17194802.

- ↑ "A Genetic Perspective on African Prehistory". Africa from MIS 6-2. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology (1): 383–405. March 2016. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7520-5_18. ISBN 978-94-017-7519-9. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/27955/1/Soares%20et%20al%20%202016%20chapter%20preprint.pdf.

- ↑ "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology 26 (6): 827–833. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. PMID 26853362.

- ↑ "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-chromosomal Haplogroup and its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics 212 (4): 1421–1428. June 2019. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMID 31196864.

- ↑ Ancient Human DNA from Shum Laka (Cameroon) in the Context of African Population History, by Lipson Mark et al., 2019 | page=5

- ↑ Martina Kujanova; Luisa Pereira; Veronica Fernandes; Joana B. Pereira; Viktor Cerny (2009). "Near Eastern Neolithic Genetic Input in a Small Oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 140 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078. PMID 19425100.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wallace, D; Brown, MD; Lott, MT (1999). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in human evolution and disease". Gene 238 (1): 211–30. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00295-4. PMID 10570998.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Pardiñas, AF; Martínez, JL; Roca, A; García-Vazquez, E; López, B (2014). "Over the sands and far away: Interpreting an Iberian mitochondrial lineage with ancient Western African origins". Am. J. Hum. Biol. 26 (6): 777–83. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22601. PMID 25130626.

- ↑ Maca-Meyer, Nicole; González, Ana M; Larruga, José M; Flores, Carlos; Cabrera, Vicente M (2001). "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genetics 2: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. PMID 11553319.

- ↑ "Cambridge DNA Services -". https://www.cambridgedna.com/genealogy-dna-ancient-migrations-slideshow.php?view=step3.

- ↑ Boru, Hirbo, Jibril (2011) (in en). Complex Genetic History of East African Human Populations. p. 118. https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/11443/Hirbo_umd_0117E_11892.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 See Supplemental_TreeUpdatedOctober.xls under the Supplementary data of Soares et al. 2011

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Hernández, Candela L; Soares, Pedro; Dugoujon, Jean M; Novelletto, Andrea; Rodríguez, Juan N; Rito, Teresa; Oliveira, Marisa; Melhaoui, Mohammed et al. (2015). "Early Holocenic and Historic mtDNA African Signatures in the Iberian Peninsula: The Andalusian Region as a Paradigm". PLOS ONE 10 (10): e0139784. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139784. PMID 26509580. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1039784H. Supplementary data doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139784.s006.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Mohamed, Hisham Yousif Hassan. "Genetic Patterns of Y-chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation, with Implications to the Peopling of the Sudan". University of Khartoum. http://khartoumspace.uofk.edu/bitstream/handle/123456789/6376/Genetic%20Patterns%20of%20Y-chromosome%20and%20Mitochondrial.pdf?sequence=1.

- ↑ Černý, Viktor; Fernandes, Verónica; Costa, Marta D; Hájek, Martin; Mulligan, Connie J; Pereira, Luísa (2009). "Migration of Chadic speaking pastoralists within Africa based on population structure of Chad Basin and phylogeography of mitochondrial L3f haplogroup". BMC Evolutionary Biology 9: 63. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-63. PMID 19309521.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Kivisild, T; Reidla, M; Metspalu, E; Rosa, A; Brehm, A; Pennarun, E; Parik, J; Geberhiwot, T et al. (2004). "Ethiopian Mitochondrial DNA Heritage: Tracking Gene Flow Across and Around the Gate of Tears". The American Journal of Human Genetics 75 (5): 752–70. doi:10.1086/425161. PMID 15457403.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Fendt, Liane; Röck, Alexander; Zimmermann, Bettina; Bodner, Martin; Thye, Thorsten; Tschentscher, Frank; Owusu-Dabo, Ellis; Göbel, Tanja M.K. et al. (2012). "MtDNA diversity of Ghana: a forensic and phylogeographic view". Forensic Science International: Genetics 6 (2): 244–49. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2011.05.011. PMID 21723214.

- ↑ Sheet1 – PLOS Pathogens

- ↑ Salas, Antonio; Richards, Martin; De la Fe, Tomás; Lareu, María-Victoria; Sobrino, Beatriz; Sánchez-Diz, Paula; Macaulay, Vincent; Carracedo, Ángel (2002-11). "The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (5): 1082–1111. ISSN 0002-9297. PMID 12395296

- ↑ Anderson, S. 2006, Phylogenetic and phylogeographic analysis of African mitochondrial DNA variation.

- ↑ Bandelt, HJ; Alves-Silva, J; Guimarães, PE; Santos, MS; Brehm, A; Pereira, L; Coppa, A; Larruga, JM et al. (2001). "Phylogeography of the human mitochondrial haplogroup L3e: a snapshot of African prehistory and Atlantic slave trade". Annals of Human Genetics 65 (Pt 6): 549–63. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6560549.x. PMID 11851985.

- ↑ Plaza, Stéphanie; Salas, Antonio; Calafell, Francesc; Corte-Real, Francisco; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Carracedo, Ángel; Comas, David (2004). "Insights into the western Bantu dispersal: mtDNA lineage analysis in Angola". Human Genetics 115 (5): 439–47. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1164-0. PMID 15340834. http://docdro.id/4zBD60N.

- ↑ Bandelt, H. J.; Alves-Silva, J.; Guimarães, P. E.; Santos, M. S.; Brehm, A.; Pereira, L.; Coppa, A.; Larruga, J. M. et al. (Nov 2011). "Phylogeography of the human mitochondrial haplogroup L3e: a snapshot of African prehistory and Atlantic slave trade". Annals of Human Genetics 65 (Pt 6): 549–563. doi:10.1017/S0003480001008892. ISSN 0003-4800. PMID 11851985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11851985/.

- ↑ Asmahan Bekada; Lara R. Arauna; Tahria Deba; Francesc Calafell; Soraya Benhamamouch; David Comas (September 24, 2015). "Genetic Heterogeneity in Algerian Human Populations". PLOS ONE 10 (9): e0138453. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138453. PMID 26402429. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1038453B.; S5 Table

- ↑ Fadhlaoui-Zid, K.; Plaza, S.; Calafell, F.; Ben Amor, M.; Comas, D.; Bennamar, A.; Gaaied, El (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Heterogeneity in Tunisian Berbers". Annals of Human Genetics 68 (Pt 3): 222–33. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00096.x. PMID 15180702.

- ↑ Stevanovitch, A.; Gilles, A.; Bouzaid, E.; Kefi, R.; Paris, F.; Gayraud, R. P.; Spadoni, J. L.; El-Chenawi, F. et al. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt". Annals of Human Genetics 68 (Pt 1): 23–39. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x. PMID 14748828.

- ↑ Fernández, Eva (2014). "Ancient DNA analysis of 8000 BC near eastern farmers supports an early neolithic pioneer maritime colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLOS Genetics 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. PMID 24901650.

- ↑ See supplementary materials from Llorente, M. Gallego; Jones, E. R.; Eriksson, A.; Siska, V.; Arthur, K. W.; Arthur, J. W.; Curtis, M. C.; Stock, J. T. et al. (13 November 2015). "Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture in Eastern Africa". Science 350 (6262): 820–822. doi:10.1126/science.aad2879. PMID 26449472. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350..820L.

- ↑ Llorente, M. Gallego; Jones, E. R.; Eriksson, A.; Siska, V.; Arthur, K. W.; Arthur, J. W.; Curtis, M. C.; Stock, J. T. et al. (2015-11-13). "Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture in Eastern Africa". Science 350 (6262): 820–822. doi:10.1126/science.aad2879. PMID 26449472. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350..820L.

- ↑ Schuenemann, Verena J. (2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMID 28556824. Bibcode: 2017NatCo...815694S.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Varela (2017). "Genomic Analyses of Pre-European Conquest Human Remains from the Canary Islands Reveal Close Affinity to Modern North Africans". Current Biology 27 (1–7): 3396–3402.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.059. PMID 29107554.

- ↑ Prendergast, Mary E.; Lipson, Mark; Sawchuk, Elizabeth A.; Olalde, Iñigo; Ogola, Christine A.; Rohland, Nadin; Sirak, Kendra A.; Adamski, Nicole et al. (2019-05-30). "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa" (in en). Science 365 (6448): eaaw6275. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31147405. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365.6275P.

- ↑ "PhyloTree.org | tree | L3". http://phylotree.org/tree/L3.htm.

Notes

- ↑ GUR46 on table 1. is a mtDNA haplogroup L3x2a.

External links

- General

- Ian Logan's Mitochondrial DNA Site

- Haplogroup L3

- Mannis van Oven's PhyloTree.org – mtDNA subtree L3

- Spread of Haplogroup L3, from National Geographic