Biology:Passiflora

| Passiflora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Passiflora incarnata | |

| |

| P. platyloba fruit, often confused with P. quadrangularis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Passifloraceae |

| Subfamily: | Passifloroideae |

| Tribe: | Passifloreae |

| Genus: | Passiflora L. |

| Species | |

|

About 550, see list | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Passiflora, known also as the passion flowers or passion vines, is a genus of about 550 species of flowering plants, the type genus of the family Passifloraceae.

They are mostly tendril-bearing vines, with some being shrubs or trees. They can be woody or herbaceous. Passion flowers produce regular and usually showy flowers with a distinctive corona. The flower is pentamerous and ripens into an indehiscent fruit with numerous seeds. For more information about the fruit of the Passiflora plant, see passionfruit.

List of species

A list of Passiflora species is found at List of Passiflora species.

Distribution

Passiflora has a largely neotropic distribution, unlike its family Passifloraceae, which includes more Old World species (such as the genus Adenia). The vast majority of Passiflora are found in Mexico, Central and South America, although there are additional representatives in the United States , Southeast Asia, and Oceania.[1] New species continue to be identified: for example, P. xishuangbannaensis and P. pardifolia have only been known to the scientific community since 2005 and 2006, respectively.

Some species of Passiflora have been naturalized beyond their native ranges. For example, the blue passion flower (P. caerulea) now grows wild in Spain.[2] The purple passionfruit (P. edulis) and its yellow relative flavicarpa have been introduced in many tropical regions as commercial crops.

Ecology

Passion flowers have unique floral structures, which in most cases require biotic pollination. Pollinators of Passiflora include bumblebees, carpenter bees (Xylocopa varipuncta), wasps, bats, and hummingbirds (especially hermits such as Phaethornis); some others are additionally capable of self-pollination. Passiflora often exhibit high levels of pollinator specificity, which has led to frequent coevolution across the genus. The sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) is a notable example: it, with its immensely elongated bill, is the sole pollinator of 37 species of high Andean Passiflora in the supersection Tacsonia.[3]

The leaves are used for feeding by the larvae of a number of species of Lepidoptera. Famously, they are exclusively targeted by many butterfly species of the tribe Heliconiini. The many defensive adaptations visible on Passiflora include diverse leaf shapes (which help disguise their identity), colored nubs (which mimic butterfly eggs and can deter Heliconians from ovipositing on a seemingly crowded leaf), extrafloral nectaries, trichomes, variegation, and chemical defenses.[4] These, combined with adaptations on the part of the butterflies, were important in the foundation of coevolutionary theory.[5][6]

The following lepidoptera larvae are known to feed on Passiflora:

- Longwing butterflies (Heliconiinae)

- Cydno longwing (Heliconius cydno), one of few Heliconians to feed on multiple species of Passiflora[7]

- Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae), which feeds on several species of Passiflora, such as Passiflora lutea, Passiflora affinis,[8][9] stinking passion flower (P. foetida),[10] and Maypop (P. incarnata)

- American Sara longwing (Heliconius sara)

- Red postman (Heliconius erato)

- Asian leopard lacewing (Cethosia cyane).

- Postman butterfly (Heliconius melpomene) prefer P. menispermifolia and P. oerstedii

- Zebra longwing (Heliconius charithonia) feed on yellow passion flower, two-flowered passion flower (P. biflora), and corky-stemmed passion flower (P. suberosa)

- Banded orange (Dryadula phaetusa) feed on P. tetrastylis

- Julia butterfly (Dryas iulia) feed on yellow passion flower and P. affinis

- Swift moth Cibyra serta

The generally high pollinator and parasite specificity in Passiflora may have led to the tremendous morphological variation in the genus. It is thought to have among the highest foliar diversity among all plant genera,[11] with leaf shapes ranging from unlobed to five-lobed frequently found on the same plant.[12] Coevolution can be a major driver of speciation, and may be responsible for the radiation of certain clades of Passiflora such as Tacsonia.

The bracts of the stinking passion flower are covered by hairs which exude a sticky fluid. Many small insects get stuck to this and get digested to nutrient-rich goo by proteases and acid phosphatases. Since the insects usually killed are rarely major pests, this passion flower seems to be a protocarnivorous plant.[13]

Banana passion flower or "banana poka" (P. tarminiana), originally from Central Brazil , is an invasive weed, especially on the islands of Hawaii. It is commonly spread by feral pigs eating the fruits. It overgrows and smothers stands of endemic vegetation, mainly on roadsides. Blue passion flower (P. caerulea) is holding its own in Spain these days, and it probably needs to be watched so that unwanted spreading can be curtailed.[2]

On the other hand, some species are endangered due to unsustainable logging and other forms of habitat destruction. For example, the Chilean passion flower (P. pinnatistipula) is a rare vine growing in the Andes from Venezuela to Chile between 2,500 and 3,800 meters altitude, and in Coastal Central Chile, where it occurs in woody Chilean Mediterranean forests. P. pinnatistipula has a round fruit, unusual in Tacsonia group species like banana passion flower and P. mixta, with their elongated tubes and brightly red to rose-colored petals.

Notable and sometimes economically significant pathogens of Passiflora are several sac fungi of the genus Septoria (including S. passiflorae), the undescribed proteobacterium called "Pseudomonas tomato" (pv. passiflorae), the Potyvirus passionfruit woodiness virus, and the Carlavirus Passiflora latent virus.

Use by humans

Ornamental

A number of species of Passiflora are cultivated outside their natural range for both their flowers and fruit. Hundreds of hybrids have been named; hybridizing is currently being done extensively for flowers, foliage and fruit. The following hybrids and cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

- 'Amethyst'[14]

- P. × exoniensis[15] (Exeter passion flower)

- P. × violacea[16]

During the Victorian era the flower (which in all but a few species lasts only one day) was very popular, and many hybrids were created using the winged-stem passion flower (P. alata), the blue passion flower (P. caerulea) and other tropical species.

Many cool-growing Passiflora from the Andes Mountains can be grown successfully for their beautiful flowers and fruit in cooler Mediterranean climates, such as the Monterey Bay and San Francisco in California and along the western coast of the U.S. into Canada . One blue passion flower or hybrid even grew to large size at Malmö Central Station in Sweden.[17]

Passion flowers have been a subject of studies investigating extranuclear inheritance; paternal inheritance of chloroplast DNA has been documented in this genus.[18] The plastome of the two-flowered passion flower (P. biflora) has been sequenced.

The French name for this plant has lent itself to La Famille Passiflore, a highly successful children's book series by Geneviève Huriet, and an animated series based upon it. These have been translated into English as Beechwood Bunny Tales and The Bellflower Bunnies.

Fruit

Most species have round or elongated edible fruit from two to eight inches long and an inch to two inches across, depending upon the species or cultivar.

- The passion fruit or maracujá (P. edulis) is cultivated extensively in the Caribbean, South America, south Florida and South Africa for its fruit, which is used as a source of juice. A small pink fruit which wrinkles easily and a larger shiny yellow to orange fruit are traded under this name. The latter is usually considered just a variety flavicarpa, but seems to be more distinct in fact.[citation needed]

- Sweet granadilla (P. ligularis) is another widely grown species. In large parts of Africa and Australia it is the plant called "passionfruit": confusingly, in South Africa n English the latter species is more often called "granadilla" (without an adjective). Its fruit is somewhat intermediate between the two sold as P. edulis.

- Maypop (P. incarnata), a common species in the southeastern US. This is a subtropical representative of this mostly tropical family. However, unlike the more tropical cousins, this particular species is hardy enough to withstand the cold down to −20 °C (−4 °F) before its roots die (it is native as far north as Pennsylvania and has been cultivated as far north as Boston and Chicago .) The fruit is sweet, yellowish, and roughly the size of a chicken's egg; it enjoys some popularity as a native plant with edible fruit and few pests.

- Giant granadilla (giant tumbo or badea, P. quadrangularis), water lemon (P. laurifolia) and sweet calabash (P. maliformis) are Passiflora species locally famed for their fruit, but not widely known elsewhere yet.

- Wild maracuja are the fruit of P. foetida, which are popular in Southeast Asia.

- Banana passionfruits are the very elongated fruits of P. tripartita var. mollissima and P. tarminiana. These are locally eaten, but their invasive properties make them a poor choice to grow outside of their native range.[19][20]

Traditional medicine

This section needs more medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (September 2015) |

P. incarnata (maypop) leaves and roots have a long history of use among Native Americans in North America and were adapted by the European colonists. The fresh or dried leaves of maypop are used to make a tea that is used for insomnia, hysteria, and epilepsy, and is also valued for its analgesic properties.[21] P. edulis (passion fruit) and a few other species are used in Central and South America for similar purposes. Once dried, the leaves can also be smoked.

The medical utility of only a few species of Passiflora has been scientifically studied.[22] In initial study in 2001 for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, maypop extract performed as well as oxazepam but with fewer short-term side effects.[23] It was recommended to follow up with long-term studies to confirm these results.

A study performed on mice demonstrated that Passiflora alata has a genotoxic effect on cells, and suggested further research was recommended before this one species is considered safe for human consumption.[24]

In another study performed with non-smoking patients, it demonstrates that oral administration of Passifora incarnata following extubation for patients surgery reduced the patients coughing versus the control group. By administering Passiflora incarnata orally with the correct dosage, it can result in antitussive activities without impairing the patient drastically. The results presented show a decrease of post extubation cough after out-patient surgery but it was only recorded early on. With this information, further research can be applied to create other medications for coughing but the authors note the limitations on the study included short observation period as well as a small sample size.[25]

Passionflower herb (Passiflorae herba) from P. incarnata is listed in the European Pharmacopoeia. The herbal drug should contain not less than 1.5% total flavonoids expressed as vitexin.[citation needed]

Passionflower is reputed to have sedative effects and has been used in sedative products in Europe, but in 1978, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibited its use in over-the-counter sedative preparations because it had not been proven safe and effective. In 2011, the University of Maryland Medical Center reported that passionflower "... can trigger side effects and can interact with other herbs, supplements, or medications. For these reasons, you should take herbs with care, under the supervision of a health care provider."[26][27]

Passionflower is classified as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for use in foods in the US,[28] and is “possibly safe when used orally and appropriately for short-term medicinal purposes,” “possibly unsafe when used in excessive amounts,” but unsafe when used orally during pregnancy since “...passionflower constituents show evidence of uterine stimulation.” The database suggests it is possibly effective for adjustment disorder with anxious mood, anxiety, and opiate withdrawal, but it “can cause dizziness, confusion, sedation, and ataxia” and there are some reports of more severe side effects including vasculitis and altered consciousness.

Chemistry

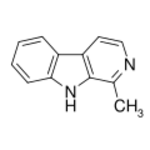

Many species of Passiflora have been found to contain beta-carboline harmala alkaloids,[22][29][30] some of which are MAO inhibitors. The flower and fruit have only traces of these chemicals, but the leaves and the roots often contain more.[30] The most common of these alkaloids is harman, but harmaline, harmalol, harmine, and harmol are also present.[22][29] The species known to bear such alkaloids include: P. actinea, P. alata (winged-stem passion flower), P. alba, P. bryonioides (cupped passion flower), P. caerulea (blue passion flower), P. capsularis, P. decaisneana, P. edulis (passion fruit), P. eichleriana, P. foetida (stinking passion flower), P. incarnata (maypop), P. quadrangularis (giant granadilla), P. suberosa, P. subpeltata and P. warmingii.[22][29]

Other compounds found in passion flowers are coumarins (e.g. scopoletin and umbelliferone), maltol, phytosterols (e.g. lutenin) and cyanogenic glycosides (e.g. gynocardin) which render some species, i.e. P. adenopoda, somewhat poisonous. Many flavonoids and their glycosides have been found in Passiflora, including apigenin, benzoflavone, homoorientin, 7-isoorientin, isoshaftoside, isovitexin (or saponaretin), kaempferol, lucenin, luteolin, n-orientin, passiflorine (named after the genus), quercetin, rutin, saponarin, shaftoside, vicenin and vitexin. Maypop, blue passion flower (P. caerulea), and perhaps others contain the flavone chrysin. Also documented to occur at least in some Passiflora in quantity are the hydrocarbon nonacosane and the anthocyanidin pelargonidin-3-diglycoside.[22][29][31]

The genus is rich in organic acids including formic, butyric, linoleic, linolenic, malic, myristic, oleic and palmitic acids as well as phenolic compounds, and the amino acid α-alanine. Esters like ethyl butyrate, ethyl caproate, n-hexyl butyrate and n-hexyl caproate give the fruits their flavor and appetizing smell. Sugars, contained mainly in the fruit, are most significantly d-fructose, d-glucose and raffinose. Among enzymes, Passiflora was found to be rich in catalase, pectin methylesterase and phenolase.[22][29]

Etymology and names

The "Passion" in "passion flower" refers to the passion of Jesus in Christian theology. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish Christian missionaries adopted the unique physical structures of this plant, particularly the numbers of its various flower parts, as symbols of the last days of Jesus and especially his crucifixion:[32]

- The pointed tips of the leaves were taken to represent the Holy Lance.

- The tendrils represent the whips used in the flagellation of Christ.

- The ten petals and sepals represent the ten faithful apostles (excluding St. Peter the denier and Judas Iscariot the betrayer).

- The flower's radial filaments, which can number more than a hundred and vary from flower to flower, represent the crown of thorns.

- The chalice-shaped ovary with its receptacle represents a hammer or the Holy Grail.

- The 3 stigmas represent the 3 nails and the 5 anthers below them the 5 wounds (four by the nails and one by the lance).

- The blue and white colors of many species' flowers represent Heaven and Purity.

The flower has been given names related to this symbolism throughout Europe since that time. In Spain , it is known as espina de Cristo ("thorn of Christ'"). Older Germanic names[33] include Christus-Krone ("Christ's crown"), Christus-Strauss ("Christ's bouquet"[34]), Dorn-Krone ("crown of thorns"), Jesus-Lijden ("Jesus' passion"), Marter ("passion"[35]) or Muttergottes-Stern ("Mother of God's star"[36]).

Outside the Roman Catholic heartland, the regularly shaped flowers have reminded people of the face of a clock. In Israel they are known as "clock-flower" (שעונית) and in Greece as "clock plant" (ρολογιά); in Japan too, they are known as tokeisō (時計草, "clock plant"). In Hawaiian, they are called lilikoʻi;[37] lī is a string used for tying fabric together, such as a shoelace, and liko means "to spring forth leaves".[38]

In India , blue passionflowers are called Krishnakamala in Karnataka and Maharashtra, while in Uttar Pradesh and generally north it is colloquially called "Paanch Paandav" (referring to the five Pandavas in the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata). The five anthers are interpreted as the five Pandavas, the divine Krishna is at the centre, and the radial filaments are opposing hundred. The colour blue is moreover associated with Krishna as the colour of his aura.

In northern Peru and Bolivia, the banana passionfruits are known as tumbos. This is one possible source of the name of the Tumbes region of Peru.

In Turkey, the shape of the flowers have reminded people of Rota Fortunae, thus it called Çarkıfelek.

Taxonomy

Passiflora is the most species rich genus of both the family Passifloraceae and the tribe Passifloreae. With over 550 species, an extensive hierarchy of infrageneric ranks is required to represent the relationships of the species. The infrageneric classification of Passiflora not only uses the widely used ranks of subgenus, section and series, but also the rank of supersection.

The New World species of Passiflora were first divided among 22 subgenera by Killip (1938) in the first monograph of the genus.[11] More recent work has reduced these to 4, which are commonly accepted today (in order from most basally to most recently branching):[39]

- Astrophea (Americas, ~60 species), trees and shrubs with simple, unlobed leaves

- Passiflora (Americas, ~250 species), woody vines with large flowers and elaborate corolla

- Deidamioides (Americas, 13 species), woody or herbaceous vines

- Decaloba (Americas, Asia and Australasia, ~230 species), herbaceous vines with palmately veined leaves

Some studies have shown that the segregate Old World genera Hollrungia and Tetrapathaea are nested within Passiflora, and form a fifth subgenus (Tetrapathaea).[40] Other studies support the current 4 subgenus classification.[41]

Relationships below the subgenus level are not known with certainty and are an active area of research. The Old World species form two clades - supersection Disemma (part of subgenus Decaloba) and subgenus Tetrapathaea. The former is composed of 21 species divided into sections Disemma (3 Australian species), Holrungiella (1 New Guinean species) and Octandranthus (17 south and east Asian species).[42]

The remaining (New World) species of subgenus Decaloba are divided into 7 supersections. Supersection Pterosperma includes 4 species from Central America and southern Mexico. Supersection Hahniopathanthus includes 5 species from Central America, Mexico and northernmost South America. Supersection Cicea includes 19 species, with apetalous flowers. Supersection Bryonioides includes 21 species, with a distribution centered on Mexico. Supersection Auriculata includes 8 species from South America, one of which is also found in Central America. Supersection Multiflora includes 19 species. Supersection Decaloba includes 123 species.[43]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Krosnick, S.E.; Porter-Utley, K.E.; MacDougal, J.M.; Jørgensen, P.M.; McDade, L.A. (2013). "New insights into the evolution of Passiflora subgenus Decaloba (Passifloraceae): phylogenetic relationships and morphological synapomorphies". Systematic Botany 38 (3): 692–713. doi:10.1600/036364413x670359. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364413X670359.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dana et al. [2001]

- ↑ Abrahamczyk, S. (2014). "Escape from extreme specialization: passionflowers, bats and the sword-billed hummingbird". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 281 (1795): 20140888. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0888. PMC 4213610. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0888.

- ↑ de Castro, É.C.P.; Zagrobelny, M.; Cardoso, M.Z.; Bak, S. (2017). "The arms race between heliconiine butterflies and Passiflora plants - new insights on an ancient subject". Biological Reviews. doi:10.1111/brv.12357. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12357.

- ↑ Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. (1964). "Butterflies and Plants: A Study in Coevolution". Evolution 18 (4): 586–608. doi:10.2307/2406212. https://www.doi.org/10.2307/2406212.

- ↑ Benson, W.W; Brown, K.S.; Gilbert, L.E. (1975). "Coevolution of plants and herbivores: passion flower butterflies". Evolution 29: 659–680. doi:10.2307/2407076. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1975.tb00861.x.

- ↑ Merrill, R.M.; Naisbit, R.E.; Mallet, J.; Jiggins, C.D. (2013). "Ecological and genetic factors influencing the transition between host-use strategies in sympatric Heliconius butterflies". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26: 1959–1967. doi:10.1111/jeb.12194.

- ↑ Knight, R.J.; Payne, J.A.; Schnell, R.J.; Amis, A.A. (1995). "‘Byron Beauty’, An Ornamental Passion Vine for the Temperate Zone". HortScience 30 (5): 1112. http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/30/5/1112.full.pdf.

- ↑ Neck, Raymond W. (1976). "Lepidopteran Foodplant Records from Texas". Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 15 (2): 75–82. http://lepidopteraresearchfoundation.org/journals/15/PDF15/15-075.pdf. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ↑ Soule, J.A. 2012. Butterfly Gardening in Southern Arizona. Tierra del Soule Press, Tucson, AZ

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Killip, E.P. (1938). The American Species of Passifloraceae. Chicago, US: Field Museum of Natural History.

- ↑ Chitwood, D.; Otoni, W. (2017). "Divergent leaf shapes among Passiflora species arise from a shared juvenile morphology". Plant Direct 1 (5). doi:10.1002/pld3.28. https://doi.org/10.1002/pld3.28.

- ↑ Radhamani et al. (1995)

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora 'Amethyst' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. http://apps.rhs.org.uk/plantselector/plant?plantid=4588. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora × exoniensis AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. http://apps.rhs.org.uk/plantselector/plant?plantid=5880. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora × violacea AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. http://apps.rhs.org.uk/plantselector/plant?plantid=5915. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Petersen (1966)

- ↑ E.g. Hansen et al. (2006)

- ↑ Smith, Clifford W.. "Impact of Alien Plants on Hawai‘i's Native Biota". University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110713071816/http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/cw_smith/impact.htm. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health and the National Park Service (17 February 2011). "Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States". http://www.invasiveplantatlas.org/subject.html?sub=6142. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ UMMC (2008) [|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Duke (2008)

- ↑ Akhondzadeh, S. (October 2001). "Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial with oxazepam". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 26 (5): 363–367. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00367.x.

- ↑ Boeira, JM; Fenner, R; Betti, AH et al. (March 2010). "Toxicity and genotoxicity evaluation of Passiflora alata Curtis (Passifloraceae)". J Ethnopharmacol 128 (2): 526–32. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.037. PMID 19799991.

- ↑ Saliminia, Alireza; Azimaraghi, Omid (June 12, 2017). "Preoperative Oral Passiflora Incarnata Reduces Coughing Following Extubation: A Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study". Archives of Anesthesiology and Critical Care 3 (3): 338–341. ISSN 2423-5849. http://aacc.tums.ac.ir/index.php/aacc/article/view/118.

- ↑ "Passionflower". nih.gov. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/871.html.

- ↑ "Passionflower". University of Maryland Medical Center. http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/herb/passionflower.

- ↑ "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". fda.gov. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=172.510.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Drugs.com (2008)

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Medicinal Plants of North America: A Field Guide By Jim Meuninck, p. 38, https://books.google.com/books?id=AVOsBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA38&ots=2Mqv0Yy6Jx&dq=native%20%22north%20america%22%20%22beta-Carboline%22&pg=PA38#v=onepage&q=beta-Carboline&f=false

- ↑ Dhawan, et al. (2002)

- ↑ Roger L. Hammer (6 January 2015). Everglades Wildflowers: A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Historic Everglades, including Big Cypress, Corkscrew, and Fakahatchee Swamps. Falcon Guides. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-1-4930-1459-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=-S0aBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA206.

- ↑ Marzell (1927)

- ↑ "Christ's flower" is a mistranslation of Marzell (1927)

- ↑ "Martyr" is a mistranslation of Marzell (1927)

- ↑ Muttergottes-Schuzchen (or -Schurzchen) is a nonsensical misreading of Marzell (1927)

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of lilikoʻi". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press. http://wehewehe.org/gsdl2.85/cgi-bin/hdict?a=q&j=pk&l=en&q=lilikoi.

- ↑ Pukui et al. (1992)

- ↑ Feuillet, C.; MacDougal, J. (2004). "A new infrageneric classification of Passiflora L. (Passifloraceae)". Passiflora 13 (2): 34–35, 37–38.

- ↑ Krosnick, S.E.; Ford, A.J.; Freudenstein, J.V. (2009). "Taxonomic Revision of Passiflora Subgenus Tetrapathea Including the Monotypic Genera Hollrungia and Tetrapathea (Passifloraceae), and a New Species of Passiflora". Systematic Botany 34 (2): 375–385. doi:10.1600/036364409788606343.

- ↑ Hansen, K.A.; Gilbert, L.E.; Simpson, B.B.; Downie, S.R.; Cervi, A.C.; Jansen, R.K. (2006). "Phylogenetic Relationships and Chromosome Number Evolution in Passiflora". Systematic Botany 31 (1): 138–150. doi:10.1600/036364406775971769.

- ↑ Shawn Elizabeth Krosnick, Ph.D. thesis, Phylogenetic relationships and patterns of morphological evolution in the Old Word species of Passiflora (subgenus Decaloba: supersection Disemma and subgenus Tetrapathaea)

- ↑ "MBG: Research: Passiflora Research Network". mobot.org. http://www.mobot.org/mobot/research/passiflora/.

References

- Akhondzadeh, Shahin; Naghavi, H.R.; Vazirian, M.; Shayeganpour, A.; Rashidi, H.; Khani, M. (2001). "Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial with oxazepam" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 26 (5): 363–367. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00367.x. http://jerrycott.com/user/passionanxiety.pdf. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- Dana, E.D.; Sanz-Elorza, M. & Sobrino, E. [2001]: Plant Invaders in Spain Check-List. PDF fulltext

- Dhawan, Kamaldeep; Kumar, Suresh; Sharma, Anupam (2002). "Beneficial Effects of Chrysin and Benzoflavone on Virility in 2-Year-Old Male Rats". Journal of Medicinal Food 5 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1089/109662002753723214.

- Drugs.com [2008]: Passion Flower. Retrieved 2008-NOV-01.

- Duke, James A. [2008]: Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases – Passiflora spp. Retrieved 2008-NOV-01.

- Hansen, A. Katie; Escobar, Linda K.; Gilbert, Lawrence E.; Jansen, Robert K. (2006). "Paternal, maternal, and biparental inheritance of the chloroplast genome in Passiflora (Passifloraceae): implications for phylogenic studies" (PDF). American Journal of Botany 94 (1): 42–46. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.1.42. PMID 21642206. http://www.amjbot.org/cgi/reprint/94/1/42.pdf.

- Marzell, Heinrich (1927): Deutsches Wörterbuch der Pflanzennamen ["German Plant Name Dictionary"]. Leipzig.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel Hoyt; Mookini, Esther T. & Nishizawa, Yu Mapuana (1992): New Pocket Hawaiian Dictionary with a Concise Grammars and Given Names in Hawaiian. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. ISBN:0-8248-1392-8

- Petersen, Elly (1966): Passionsblume ["Passion flowers"]. In: Praktisches Gartenlexikon der Büchergilde (2nd ed.): 270-271 [in German]. Büchergilde Gutenberg. Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, Zürich.

- Radhamani, T.R.; Sudarshana, L.; Krishnan, R. (1995). "Defence and carnivory: dual roles of bracts". Passiflora foetida. Journal of Biosciences 20 (5): 657–664. doi:10.1007/BF02703305.

- University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) (2008): Passionflower. Retrieved 2008-NOV-01.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Passion-flower. |

- The Passiflora Society International

- Killip, The American Species of Passifloraceae, Fieldiana, Bot. 19 (1938)

- Passiflora online

- Passiflora edulis

- Passiflora Picture Gallery

- Chilean Passiflora pictures

- A list of Heliconius Butterflies and the Passiflora species their larvae consume

Wikidata ☰ Q161185 entry

|