Biology:Barley

| Barley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Hordeum |

| Species: | H. vulgare

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hordeum vulgare | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Barley (Hordeum vulgare), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9,000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikelets and making it much easier to harvest. Its use then spread throughout Eurasia by 2,000 BC. Barley prefers relatively low temperatures to grow, and well-drained soil. It is relatively tolerant of drought and soil salinity, but is less winter-hardy than wheat or rye.

In 2022, barley was fourth among grains in quantity produced, 155 million tonnes, behind maize, wheat, and rice. Globally 70% of barley production is used as animal feed, while 30% is used as a source of fermentable material for beer, or further distilled into whisky, and as a component of various foods. It is used in soups and stews, and in barley bread of various cultures. Barley grains are commonly made into malt in a traditional and ancient method of preparation. In English folklore, John Barleycorn personifies the grain, and the alcoholic beverages made from it. English pub names such as The Barley Mow allude to barley's role in the production of beer.

Etymology

The Old English word for barley was bere;[3] it survives in the north of Scotland as bere; it is used for a strain of six-row barley grown there.[4] Modern English barley derives from the Old English adjective bærlic, meaning "of barley".[5][6] The word barn derives from Old English bere-aern meaning "barley-store".[5]

The name of the genus is from Latin hordeum, barley, likely related to Latin horrere, to bristle.[7]

Description

Barley is a cereal, a member of the grass family with edible grains. Its flowers are clusters of spikelets arranged in a distinctive herringbone pattern. Each spikelet has a long thin awn (to 160 mm (6.3 in) long), making the ears look tufted. The spikelets are in clusters of three. In six-row barley, all three spikelets in each cluster are fertile; in two-row barley, only the central one is fertile.[8] It is a self-pollinating, diploid species with 14 chromosomes.[9]

The genome of barley was sequenced in 2012 by the International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium and the UK Barley Sequencing Consortium.[10] The genome is organised into seven pairs[11] of nuclear chromosomes (recommended designations: 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H and 7H), and one mitochondrial and one chloroplast chromosome, with a total of 5000 Mbp.[12] Details of the genome are freely available in several barley databases.[13]

Origin

External phylogeny

The barley genus Hordeum is relatively closely related to wheat and rye within the Triticeae, and more distantly to rice within the BOP clade of grasses (Poaceae).[14] The phylogeny of the Triticeae is complicated by horizontal gene transfer between species, so there is a network of relationships rather than a simple inheritance-based tree.[15]

| (Part of Poaceae) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Domestication

Barley was one of the first grains to be domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, an area of relatively abundant water in Western Asia,[17] around 9,000 BC.[18][16] Wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) ranges from North Africa and Crete in the west to Tibet in the east.[9] A study of genome-wide diversity markers found Tibet to be an additional center of domestication of cultivated barley.[19] The earliest archaeological evidence of the consumption of wild barley, Hordeum spontaneum, comes from the Epipaleolithic at Ohalo II at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, where grinding stones with traces of starch were found. The remains were dated to about 23,000 BC.[9][20][21] The earliest evidence for the domestication of barley, in the form of cultivars that cannot reproduce without human assistance, comes from Mesopotamia, specifically the Jarmo region of modern-day Iraq, around 9,000-7,000 BC.[22][23]

Domestication changed the morphology of the barley grain substantially, from an elongated shape to a more rounded spherical one.[24] Wild barley has distinctive genes, alleles, and regulators with potential for resistance to abiotic or biotic stresses; these may help cultivated barley to adapt to climatic changes.[25] Wild barley has a brittle spike; upon maturity, the spikelets separate, facilitating seed dispersal. Domesticated barley has nonshattering spikelets, making it much easier to harvest the mature ears.[9] The nonshattering condition is caused by a mutation in one of two tightly linked genes known as Bt1 and Bt2; many cultivars possess both mutations. The nonshattering condition is recessive, so varieties of barley that exhibit this condition are homozygous for the mutant allele.[9] Domestication in barley is followed by the change of key phenotypic traits at the genetic level.[26]

The wild barley found currently in the Fertile Crescent may not be the progenitor of the barley cultivated in Eritrea and Ethiopia, indicating that it may have been domesticated separately in eastern Africa.[27]

Spread

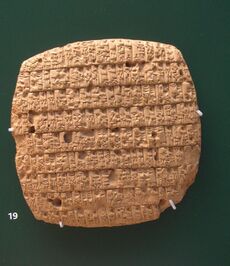

Archaeobotanical evidence shows that barley had spread throughout Eurasia by 2,000 BC.[16] Genetic analysis demonstrates that cultivated barley followed several different routes over time.[16] By 4200 BC domesticated barley had reached Eastern Finland.[28] Barley has been grown in the Korean Peninsula since the Early Mumun Pottery Period (circa 1500–850 BC).[29] Barley (Yava in Sanskrit) is mentioned many times in the Rigveda and other Indian scriptures as a principal grain in ancient India.[30] Traces of barley cultivation have been found in post-Neolithic Bronze Age Harappan civilization 5,700–3,300 years ago.[31] Barley beer was probably one of the first alcoholic drinks developed by Neolithic humans;[32] later it was used as currency.[32] The Sumerian language had a word for barley, akiti. In ancient Mesopotamia, a stalk of barley was the primary symbol of the goddess Shala.[33]

| jt barley determinative/ideogram | <hiero>M34</hiero> |

| jt (common) spelling | <hiero>i-t-U9:M33</hiero> |

| šma determinative/ideogram | <hiero>U9</hiero> |

Rations of barley for workers appear in Linear B tablets in Mycenaean contexts at Knossos and at Mycenaean Pylos.[34] In mainland Greece, the ritual significance of barley possibly dates back to the earliest stages of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The preparatory kykeon or mixed drink of the initiates, prepared from barley and herbs, mentioned in the Homeric hymn to Demeter. The goddess's name may have meant "barley-mother", incorporating the ancient Cretan word δηαί (dēai), "barley".[35][36] The practice was to dry the barley groats and roast them before preparing the porridge, according to Pliny the Elder's Natural History.[37] Tibetan barley has been a staple food in Tibetan cuisine since the fifth century AD. This grain, along with a cool climate that permitted storage, produced a civilization that was able to raise great armies.[38] It is made into a flour product called tsampa that is still a staple in Tibet.[39] In medieval Europe, bread made from barley and rye was peasant food, while wheat products were consumed by the upper classes.[40] Potatoes largely replaced barley in Eastern Europe in the 19th century.[41]

Taxonomy and varieties

Two-row and six-row barley

Spikelets are arranged in triplets which alternate along the rachis. In wild barley (and other Old World species of Hordeum), only the central spikelet is fertile, while the other two are reduced. This condition is retained in certain cultivars known as two-row barleys. A pair of mutations (one dominant, the other recessive) result in fertile lateral spikelets to produce six-row barleys.[9] A mutation in one gene, vrs1, is responsible for the transition from two-row to six-row barley.[42]

In traditional taxonomy, different forms of barley were classified as different species based on morphological differences. Two-row barley with shattering spikes (wild barley) was named Hordeum spontaneum (K. Koch). Two-row barley with nonshattering spikes was named as H. distichon (L.), six-row barley with nonshattering spikes as H. vulgare L. (or H. hexastichum L.), and six-row with shattering spikes as H. agriocrithon Åberg. Because these differences were driven by single-gene mutations, coupled with cytological and molecular evidence, most recent classifications treat these forms as a single species, H. vulgare L.[9]

6-row barley has three fertile spikelets per cluster

Hulless barley

Hulless or "naked" barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f.) is a form of domesticated barley with an easier-to-remove hull. Naked barley is an ancient food crop, but a new industry has developed around uses of selected hulless barley to increase the digestibility the grain, especially for pigs and poultry.[43] Hulless barley has been investigated for several potential new applications as whole grain, bran, and flour.[44]

| Barley production – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions of tonnes |

| 23.4 | |

| 11.3 | |

| 11.2 | |

| 10.0 | |

| 8.5 | |

| 7.0 | |

| World | 154.9[45] |

Production

In 2022, world production of barley was 155 million tonnes, led by Russia accounting for 15% of the world total (table). France , Germany , and Canada were secondary producers. Worldwide barley production was fourth among grains, following maize (1.2 billion tonnes), wheat (808 million tonnes), and rice (776 million tonnes).[46]

Cultivation

Barley is a crop that prefers relatively low temperatures, 15 to 20 °C in the growing season; it is grown around the world in temperate areas. It grows best in well-drained soil in full sunshine. In the tropics and subtropics, it is grown for food and straw in South Asia, North and East Africa, and in the Andes of South America. In dry regions it requires irrigation.[47] It has a short growing season and is relatively drought tolerant.[40] Barley is more tolerant of soil salinity than other cereals, varying in different cultivars.[48] It has less winter-hardiness than winter wheat and far less than rye.[49]

Like other cereals, barley is typically planted on tilled land. Seed was traditionally scattered, but in developed countries is usually drilled. As it grows it requires soil nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium), often supplied as fertilizers. It to be monitored for pests and diseases, and if necessary treated before these become serious. The stems and ears turn yellow when ripe, and the ears begin to droop. Traditional harvesting was by hand with sickles or scythes; in developed countries, harvesting is mechanised with combine harvesters.[47]

Spraying barley for rust fungus,

New Zealand, 1979Traditional barley harvest by hand with scythes, England, c. 1886.

Photo Peter Henry EmersonHarvesting winter barley with a combine harvester, Germany, 2017

Pests and diseases

Among the insect pests of barley are aphids such as Russian wheat aphid, caterpillars such as of the armyworm moth, barley mealybug, and wireworm larvae of click beetle genera such as Aeolus. Aphid damage can often be tolerated, whereas armyworms can eat whole leaves. Wireworms kill seedlings, and require seed or preplanting treatment.[47]

Serious fungal diseases of barley include powdery mildew caused by Blumeria graminis, leaf scald caused by Rhynchosporium secalis, barley rust caused by Puccinia hordei, crown rust caused by Puccinia coronata, various diseases caused by Cochliobolus sativus, Fusarium ear blight,[50] and stem rust (Puccinia graminis).[51] Bacterial diseases of barley include bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. translucens.[52] Barley is susceptible to several viral diseases, such as barley mild mosaic bymovirus.[53][54] Some viruses, such as barley yellow dwarf virus, vectored by the rice root aphid, can cause serious crop injury.[55]

For durable disease resistance, quantitative resistance is more important than qualitative resistance. The most important foliar diseases have corresponding resistance gene regions on all chromosomes of barley.[11] A large number of molecular markers are available for breeding of resistance to leaf rust, powdery mildew, Rhynchosporium secalis, Pyrenophora teres f. teres, Barley yellow dwarf virus, and the Barley yellow mosaic virus complex.[56][57]

Barley rust, a disease caused by the fungus Puccinia hordei

Food

| |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 515 kJ (123 kcal) |

28.2 g | |

| Sugars | 0.3 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.8 g |

0.4 g | |

2.3 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 0 μg0% 5 μg56 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 7% 0.083 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.062 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 14% 2.063 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 3% 0.135 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 9% 0.115 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 16 μg |

| Vitamin B12 | 0% 0 μg |

| Choline | 3% 13.4 mg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin D | 0% 0 IU |

| Vitamin E | 0% 0.01 mg |

| Vitamin K | 1% 0.8 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 11 mg |

| Copper | 5% 0.105 mg |

| Iron | 10% 1.3 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 22 mg |

| Manganese | 12% 0.259 mg |

| Phosphorus | 8% 54 mg |

| Potassium | 2% 93 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 3 mg |

| Zinc | 9% 0.82 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 68.8 g |

| Cholesterol | 0 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Preparation

Hulled barley (or covered barley) is eaten after removing the inedible, fibrous, outer husk or hull. Once removed, it is called dehulled barley (or pot barley or scotch barley).[58] Pearl barley (or pearled barley) is dehulled to remove most of the bran, and polished.[58] Barley meal, a wholemeal barley flour lighter than wheat meal but darker in colour, is used in gruel.[58] This gruel is known as سويق : sawīq in the Arab world.[59]

With a long history of cultivation in the Middle East, barley is used in a wide range of traditional Arabic, Assyrian, Israelite, Kurdish, and Persian foodstuffs including Keşkek, kashk, and murri. Barley soup is traditionally eaten during Ramadan in Saudi Arabia.[60] Cholent or hamin (in Hebrew) is a traditional Jewish stew often eaten on Sabbath, in numerous recipes by both Mizrachi and Ashkenazi Jews; its original form was a barley porridge.[61]

In Eastern and Central Europe, barley is used in soups and stews such as ričet. In Africa, where it is a traditional food plant, it has the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development, and support sustainable landcare.[62]

The six-row variety bere is cultivated in Orkney, Shetland, Caithness and the Western Isles of the Scottish Highlands and Islands. When milled into beremeal, it is used locally in bread, biscuits, and the traditional beremeal bannock.[63]

In Japanese cuisine, barley is mixed with rice and steamed as mugimeshi.[64] The naval surgeon Takaki Kanehiro introduced it into institutional cooking to combat beriberi, endemic in the armed forces in the 19th century. It became standard prison fare, and remains a staple in the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[65]

Nutrition

Cooked barley is 69% water, 28% carbohydrates, 2% protein, and 0.4% fat (table). In a 100-gram (3.5 oz) reference serving, cooked barley provides 515 kilojoules (123 kcal) of food energy and is a good source (10% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of essential nutrients, including, dietary fibre, the B vitamin, niacin (14% DV), and dietary minerals, including iron (10% DV) and manganese (12% DV) (table).[66]

Health implications

According to Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration, consuming at least 3 grams per day of barley beta-glucan can lower levels of blood cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.[67][68] Eating whole-grain barley, a high-fibre grain, improves regulation of blood sugar (i.e., reduces blood glucose response to a meal).[69] Consuming breakfast cereals containing barley over weeks to months improves cholesterol levels and glucose regulation.[70] Barley contains gluten, which makes it an unsuitable grain for consumption by people with gluten-related disorders, such as coeliac disease, non-coeliac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy sufferers.[71] Nevertheless, some wheat allergy patients can tolerate barley.[72]

Uses

Beer, whisky, and soft drinks

Barley, made into malt, is a key ingredient in beer and whisky production. Two-row barley is traditionally used in German and English beers. Six-row barley was traditionally used in US beers, but both varieties are in common usage now.[73] Distilled from green beer,[74] Scottish and Irish whisky are made primarily from barley.[75] About 25% of American barley is used for malting, for which barley is the best-suited grain.[76] Accordingly, barley is often assessed by its malting enzyme content.[11] Barley wine is a style of strong beer from the English brewing tradition. An 18th century alcoholic drink of the same name was made by boiling barley in water, then mixing the barley water with white wine, borage, lemon and sugar. In the 19th century, a different barley wine was prepared from recipes of ancient Greek origin.[5]

Nonalcoholic drinks such as barley water[5] and roasted barley tea have been made by boiling barley in water.[77] In Italy, barley is sometimes used as coffee substitute, caffè d'orzo (barley coffee).[78]

Animal feed

Some 70% of the world's barley production is used as livestock feed,[79] for example for cattle feeding in western Canada.[80] In 2014, an enzymatic process was devised to make a high-protein fish feed from barley, suitable for carnivorous fish such as trout and salmon.[81]

Other uses

Barley straw has been placed in mesh bags and floated in fish ponds or water gardens to help prevent algal growth without harming pond plants and animals. The technique's effectiveness is at best mixed.[82] Barley grains were once used for measurement in England, there being nominally three or four barleycorns to the inch.[83] By the 19th century, this had been superseded by standard inch measures.[84]

Culture and folklore

In English folklore, the figure of John Barleycorn in the folksong of the same name is a personification of barley, and of the alcoholic beverages made from it: beer and whisky. In the song, John Barleycorn is represented as suffering attacks, death, and indignities that correspond to the various stages of barley cultivation, such as reaping and malting; but he is revenged by getting the men drunk: "And little Sir John and the nut-brown bowl / Proved the strongest man at last."[85][86] The folksong "Elsie Marley" celebrates an alewife of County Durham with lines such as "And do you ken Elsie Marley, honey? / The wife that sells the barley, honey". The antiquary Cuthbert Sharp records that Elsie Marley was "a handsome, buxom, bustling landlady, and brought good custom to the [ale] house by her civility and attention."[87]

English pub names such as The Barley Mow,[88] John Barleycorn,[85] Malt Shovel,[89] and Mash Tun[90] allude to barley's role in the production of beer.[88]

English pub names such as The Barley Mow (like this pub at Clifton Hampden) allude to the use of barley to make the beer available inside.[88]

References

- ↑ "Hordeum vulgare". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=40874.

- ↑ "Hordeum vulgare L.". http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-419563.

- ↑ Clark Hall, J. R. (2002). "A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary". A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press. p. 43.

- ↑ "Dictionary of the Scots Language: "DSL - DOST Bere, Beir"". http://www.dsl.ac.uk/dsl/getent4.php?plen=18327&startset=1964317&query=BEAR&fhit=bere&dregion=form&dtext=snd#fhit.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ayto, John (1990). The glutton's glossary : a dictionary of food and drink terms. London: Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-415-02647-5. https://archive.org/details/gluttonsglossary00ayto. "barley water was used."

- ↑ "Barley". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8. https://www.oed.com/dictionary/barley_n?tab=factsheet#27369726.

- ↑ "hordeum noun". Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hordeum.

- ↑ "Hordeum vulgare — common barley". Native Plant Trust. https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/hordeum/vulgare/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria (2000). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 59–69. ISBN 978-0-19-850357-6.

- ↑ The International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium (2012). "A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome". Nature 491 (7426): 711–716. doi:10.1038/nature11543. PMID 23075845. Bibcode: 2012Natur.491..711T. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11543.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Hayes, Patrick M. et al. (2003). "Genetic diversity for quantitatively inherited agronomic and malting quality traits". in Roland von Bothmer. Diversity in Barley (Hordeum vulgare). Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier. pp. 201–226. doi:10.1016/S0168-7972(03)80012-9. ISBN 978-0-444-50585-9. OCLC 162130976.

- ↑ mapview. "barley genome at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/map_search.cgi?chr=barley.inf.

- ↑ "Background: The barley genome". UK Barley Sequencing Consortium. 2024. https://www.barleygenome.org.uk/genome/background.

- ↑ Soreng, Robert J.; Peterson, Paul M.; Romaschenko, Konstantin; Davidse, Gerrit; Zuloaga, Fernando O. et al. (2015). "A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae)". Journal of Systematics and Evolution 53 (2): 117–137. doi:10.1111/jse.12150.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Jones, Martin K.; Kovaleva, Olga (18 July 2018). "Barley heads east: Genetic analyses reveal routes of spread through diverse Eurasian landscapes". PLOS ONE 13 (7): e0196652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196652. PMID 30020920. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1396652L.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Jones, Martin K.; Kovaleva, Olga (18 July 2018). "Barley heads east: Genetic analyses reveal routes of spread through diverse Eurasian landscapes". PLOS ONE 13 (7): e0196652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196652. PMID 30020920. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1396652L.

- ↑ Badr, A.; M, K.; Sch, R.; El Rabey, H.; Effgen, S. et al. (2000-04-01). "On the Origin and Domestication History of Barley (Hordeum vulgare)". Molecular Biology and Evolution 17 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026330. PMID 10742042.

- ↑ Mascher, Martin; Schuenemann, Verena J; Davidovich, Uri; Marom, Nimrod; Himmelbach, Axel et al. (2016). "Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley". Nat. Genet. 48 (9): 1089–1093. doi:10.1038/ng.3611. PMID 27428749. https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/en/publications/15d655f0-3be9-4ed4-9338-7c34a1e08754.

- ↑ Dai, Fei et al. (2012-10-16). "Tibet is one of the centers of domestication of cultivated barley". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (42): 16969–16973. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215265109. PMID 23033493. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..10916969D.

- ↑ Nadel, Dani; Piperno, Dolores R.; Holst, Irene; Snir, Ainit; Weiss, Ehud (December 2012). "New evidence for the processing of wild cereal grains at Ohalo II, a 23 000-year-old campsite on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel". Antiquity 86 (334): 990–1003. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00048201. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00048201. "Traces of starch found on a large flat stone discovered in the hunter-fisher-gatherer site of Ohalo II famously represent the first identification of Upper Palaeolithic grinding of grasses. Given the importance of this discovery for the use of edible grain, further analyses have now been undertaken. Meticulous sampling combined with good preservation allow the authors to demonstrate that the Ohalo II stone was certainly used for the routine processing of wild cereals, wheat, barley and now oats among them, around 23 000 years ago.".

- ↑ Snir, Ainit; Nadel, Dani; Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Melamed, Yoel; Sternberg, Marcelo; Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Weiss, Ehud (July 22, 2015). "The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming". PLOS ONE 10 (7): e0131422. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422. PMID 26200895. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1031422S.

- ↑ Ucko, Peter John; Dimbleby, G. W. (1 January 2007). The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals. Transaction Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-202-36557-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=6lY9Q4vnrCEC&pg=PA164. "This feature allows us to describe the Jarmo barley as the earliest "domesticated" two-row barley yet found."

- ↑ Clark, Helena H. (1967). "The Origin and Early History of the Cultivated Barleys: A Botanical and Archaeological Synthesis". The Agricultural History Review 15 (1): 10–11.

- ↑ Hughes, N.; Oliveira, H. R.; Fradgley, N.; Corke, F.; Cockram, J.; Doonan, J. H.; Nibau, C. (14 March 2019). "μCT trait analysis reveals morphometric differences between domesticated temperate small grain cereals and their wild relatives". The Plant Journal (Wiley-Blackwell) 99 (1): 98–111. doi:10.1111/tpj.14312. PMID 30868647.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaolei et al. (2018-05-15). "Genomic adaptation to drought in wild barley is driven by edaphic natural selection at the Tabigha Evolution Slope". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (20): 5223–5228. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721749115. PMID 29712833. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.5223W.

- ↑ Yan, S.; Sun, D.; Sun, G. (2015-03-26). "Genetic divergence in domesticated and non-domesticated gene regions of barley chromosomes". PLOS ONE 10 (3): e0121106. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121106. PMID 25812037. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1021106Y.

- ↑ Orabi, Jihad; Backes, Gunter; Wolday, Asmelash; Yahyaoui, Amor; Jahoor, Ahmed (2007-03-29). "The Horn of Africa as a centre of barley diversification and a potential domestication site". Theoretical and Applied Genetics 114 (6): 1117–1127. doi:10.1007/s00122-007-0505-5. PMID 17279366.

- ↑ "Maanviljely levisi Suomeen Itä-Aasiasta jo 7000 vuotta sitten - Ajankohtaista - Tammikuu 2013 - Humanistinen tiedekunta - Helsingin yliopisto" (in Finnish). http://www.helsinki.fi/hum/ajankohtaista/2013/01/0128b.htm.

- ↑ Crawford, Gary W.; Gyoung-Ah Lee (2003). "Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula". Antiquity 77 (295): 87–95. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00061378.

- ↑ Witzel, Michael E. J.. "The Linguistic History of Some Indian Domestic Plants". Harvard University. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/8954814/Witzel_Linguistic.pdf?sequence=1.

- ↑ "Indus Valley civilization". IIT Kharagpur. https://iitkgp.org/content/iit-kgp-researchers-say-indus-valley-civilization-india-older-thought.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Pellechia, Thomas (2006). Wine : the 8,000-year-old story of the wine trade. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56025-871-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=K6OTKiIlyAIC&q=barley+beer+first+drink&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=05LXAAAAMAAJ&q=Inana.

- ↑ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–. ISBN 0-521-29037-6. https://archive.org/details/mycenaeanworld00chad.

- ↑ Tobin, Vincent Arieh (1991). "Isis and Demeter: symbols of divine motherhood". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 28: 187–200. doi:10.2307/40000579. OCLC 936727983. "Demeter's name, therefore, could be interpreted in Greek to mean 'barley-mother'".

- ↑ J. Dobraszczyk, Bogdan (2001). Cereals and cereal products: chemistry and technology. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8342-1767-6.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. Natural History, xviii.72.

- ↑ Fernandez, Felipe Armesto (2001). Civilizations: Culture, Ambition and the Transformation of Nature. Simon & Schuster. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-7432-1650-0.

- ↑ Dreyer, June Teufel; Sautman, Barry (2006). Contemporary Tibet: politics, development, and society in a disputed region. Armonk, New York: Sharpe. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7656-1354-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ou4f4q8gGcIC&q=tsampa&pg=PA262.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 McGee 1986, p. 235

- ↑ Roden, Claudia (1997). The Book of Jewish Food. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-394-53258-5. https://archive.org/details/bookofjewishfood00rode/page/135.

- ↑ Komatsuda, Takao et al. (2007-01-23). "Six-rowed barley originated from a mutation in a homeodomain-leucine zipper I-class homeobox gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (4): 1424–1429. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608580104. PMID 17220272. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.1424K.

- ↑ Bhatty, R. S. (1999). "The potential of hull-less barley". Cereal Chemistry 76 (5): 589–599. doi:10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.5.589.

- ↑ Bhatty, R. S. (2011). "β-glucan and flour yield of hull-less barley". Cereal Chemistry 76 (2): 314–315. doi:10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.2.314.

- ↑ "Barley production in 2022; Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (from pick lists)". FAOSTAT, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database. 2024. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

- ↑ "Comparison of world production values in 2022; maize-wheat-rice-barley". FAOSTAT, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database. 2024. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#compare.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Barley". https://plantvillage.psu.edu/topics/barley/infos.

- ↑ Witzel, Katja; Matros, Andrea; Strickert, Marc; Kaspar, Stephanie; Peukert, Manuela; Mühling, Karl H.; Börner, Andreas; Mock, Hans-Peter (2014). "Salinity Stress in Roots of Contrasting Barley Genotypes Reveals Time-Distinct and Genotype-Specific Patterns for Defined Proteins". Molecular Plant 7 (2): 336–355. doi:10.1093/mp/sst063. PMID 24004485.

- ↑ "Winter-hardiness". Stockinger Lab, Ohio State University. https://stockingerlab.osu.edu/winter-hardiness.

- ↑ Parry, D. W.; Jenkinson, P.; McLeod, L. (1995). "Fusarium ear blight (scab) in small grain cereals—a review". Plant Pathology 44 (2): 207–238. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.1995.tb02773.x.

- ↑ Djurle, Annika; Young, Beth; Berlin, Anna; Vågsholm, Ivar; Blomström, Anne-Lie; Nygren, Jim; Kvarnheden, Anders (2022). "Addressing biohazards to food security in primary production". Food Security 14 (6): 1475–1497. doi:10.1007/s12571-022-01296-7.

- ↑ Mathre, D. E. (1997). Compendium of barley diseases. American Phytopathological Society. pp. 120.

- ↑ Brunt, A. A.; Crabtree, K.; Dallwitz, M. J. et al., eds (20 August 1996). "Plant Viruses Online: Descriptions and Lists from the VIDE Database". http://image.fs.uidaho.edu/vide/refs.htm.

- ↑ "Barley mild mosaic bymovirus". http://image.fs.uidaho.edu/vide/descr059.htm.

- ↑ Jedlinski, H. (1981). "Rice Root Aphid, Rhopalosiphum rufiabdominalis, a Vector of Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus in Illinois, and the Disease Complex". Plant Disease (American Phytopathological Society) 65 (12): 975. doi:10.1094/pd-65-975.

- ↑ Chelkowski, Jerzy; Tyrka, Miroslaw; Sobkiewicz, Andrzej (2003). "Resistance genes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and their identification with molecular marker". Journal of Applied Genetics 44 (3): 291–309. PMID 12923305.

- ↑ Miedaner, T.; Korzun, V. (2012). "Marker-Assisted Selection for Disease Resistance in Wheat and Barley Breeding". Phytopathology 102 (6): 560–566. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-05-11-0157. PMID 22568813.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Simon, André (1963). Guide to Good Food and Wines: A Concise Encyclopedia of Gastronomy Complete and Unabridged. London: Collins. p. 150.

- ↑ Tabari (1987). "Muhammad at Al-Madina, A. D. 622-626/ijrah-4 A. H.". The History of Al-Tabari. VII: The Foundation of the Community. SUNY Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-88706-344-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=ctvk-fdtklYC&q=barley+sawiq&pg=PA89.

- ↑ Long, David E. (2005). Culture and customs of Saudi Arabia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-313-32021-7. https://archive.org/details/culturecustomsof00long/page/50.

- ↑ Marks, Gil (2010). "Cholent/Schalet". Encyclopedia of Jewish Foods. HMH. pp. 40.

- ↑ National Research Council (1996-02-14). "Other Cultivated Grains". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. 1. National Academies Press. p. 243. doi:10.17226/2305. ISBN 978-0-309-04990-0. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2305&page=237. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Martin, Peter; Chang, Xianmin (June 2008). "Bere Whisky: rediscovering the spirit of an old barley". The Brewer & Distiller International 4 (6): 41–43. http://www.ibd.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Sano, Anna; Tsuyukubo, Mika; Mabashi, Yuka; Murakami, Yukie; Narita, Hiroshi; Kasai, Midori; Ookura, Tetsuya (2017). "Translocation of Barley β-amylase into Rice Grains during Cooking Rice Mixed with Barley (Mugimeshi)". Food Science and Technology Research 23 (4): 621–625. doi:10.3136/fstr.23.621.

- ↑ Yoji, Yamazaki (2008). "Kanehiro Takaki : The Great Naval Surgeon Nicknamed the "Barley Baron"". 日本腹部救急医学会雑誌 (CiNii) 28. doi:10.11231/jaem.28.873. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1390001204733516160?lang=en. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ↑ USDA Database entry Accessed 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "21 CFR Part 101 [Docket No. 2004P-0512, Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soluble Dietary Fiber From Certain Foods and Coronary Heart Disease"]. US Food and Drug Administration. 22 May 2006. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=101.81.

- ↑ "Summary of Health Canada's Assessment of a Health Claim about Barley Products and Blood Cholesterol Lowering". Health Canada. 12 July 2012. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/label-etiquet/claims-reclam/assess-evalu/barley-orge-eng.php.

- ↑ Harris, Kristina A.; Kris-Etherton, Penny M. (2010). "Effects of Whole Grains on Coronary Heart Disease Risk". Current Atherosclerosis Reports 12 (6): 368–376. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0136-1.

- ↑ Williams, P. G. (September 2014). "The benefits of breakfast cereal consumption: a systematic review of the evidence base". Advances in Nutrition 5 (5): 636S–673S. doi:10.3945/an.114.006247. PMID 25225349.

- ↑ Tovoli, F.; Masi, C.; Guidetti, E.; Negrini, G.; Paterini, P.; Bolondi, L. (March 2015). "Clinical and Diagnostic Aspects of Gluten Related Disorders". World Journal of Clinical Cases 3 (3): 275–84. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275. PMID 25789300.

- ↑ Pietzak, M. (January 2012). "Celiac disease, wheat allergy, and gluten sensitivity: when gluten free is not a fad". Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 36 (1 Suppl): 68S–75S. doi:10.1177/0148607111426276. PMID 22237879.

- ↑ Ogle, Maureen (2006). Ambitious brew : the story of American beer. Orlando: Harcourt. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-0-15-101012-7. https://archive.org/details/ambitiousbrewsto00maur. "and six-row barley was traditionally used in US beers."

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 481

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 490

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 471

- ↑ Clarke, R. J., ed (1988). Coffee. London: Elsevier Applied Science. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-85166-103-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=n9ZEMquvPoYC&q=mugicha&pg=PA84.

- ↑ "Caffè d'orzo: il caffè senza caffeina" (in Italian). https://www.cibo360.it/alimentazione/cibi/bevande_analcoliche/caffe_orzo.htm.

- ↑ Akar, Taner; Avci, Muzaffer; Dusunceli, Fazil (15 June 2004). "Barley: Post-Harvest Operations". Food and Agriculture Organization. https://www.fao.org/3/a-au997e.pdf.

- ↑ "Corn or Barley for Feeding Steers?". Government of Ontario. http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock/beef/news/vbn0804a3.htm.

- ↑ Avant, Sandra (2014-07-14). "Process Turns Barley into High-protein Fish Food". USDA Agricultural Research Service. https://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2014/140714.htm.

- ↑ Lembi, Carole A.. "Barley straw for algae control". Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana. http://www.btny.purdue.edu/pubs/APM/APM-1-W.pdf.

- ↑ "Barleycorn". Collins Dictionary. 2023. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/barleycorn.

- ↑ George Long (1842). "Standard Measure, Weight". The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 26, Ungulata - Wales. C. Knight. p. 436. https://archive.org/details/pennycyclopdias16longgoog.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-7204-8021-4. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofsymb0000vrie/page/34.

- ↑ "John Barleycorn Must Die". University of Arkansas Press. https://www.uapress.com/product/john-barleycorn-must-die/.

- ↑ Sharp, Cuthbert (1834). "The Bishoprick Garland or a Collection of Legends, Songs, Ballads, &c.". p. 48. https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/82881/SC_CuthbertSharp_ed_Bishoprick_1834.pdf;jsessionid=B5030120D13E39DBC005322747FB6553?sequence=2.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 "A history of British pub names". The History Press. https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/a-history-of-british-pub-names/.

- ↑ "Middle Level". Lynn Advertiser: p. 8. 19 March 1870.

- ↑ "The Mash Tun: Brighton's Beating Heart". https://www.mashtun.pub/.

Sources

- McGee, Harold (1986). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-440277-0.

Wikidata ☰ Q11577 entry

|