Biology:Malassezia

| Malassezia | |

|---|---|

| |

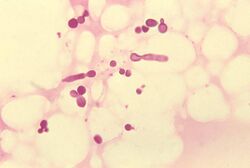

| Malassezia furfur in skin scale from a patient with tinea versicolor | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision: | Ustilaginomycotina |

| Class: | Malasseziomycetes Denchev & T.Denchev (2014) |

| Order: | Malasseziales R.T.Moore (1980) |

| Family: | Malasseziaceae Denchev & R.T.Moore (2009) |

| Genus: | Malassezia Baill. (1889)[1] |

| Type species | |

| Malassezia furfur (C.P.Robin) Baill. (1889)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Malassezia (formerly known as Pityrosporum) is a genus of fungi. It is the sole genus in family Malasseziaceae, which is the only family in order Malasseziales, itself the single member of class Malasseziomycetes.[3] Malassezia species are naturally found on the skin surfaces of many animals, including humans. In occasional opportunistic infections, some species can cause hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation on the trunk and other locations in humans. Allergy tests for these fungi are available. It is believed French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat suffered from a fungal infection from Malassezia restricta, which lead to his frequent bathing in a medicinal substance.[4]

Systematics

Due to progressive changes in their nomenclature, some confusion exists about the naming and classification of Malassezia yeast species. Work on these yeasts has been complicated because they require specific growth media and grow very slowly in laboratory culture.[6]

Malassezia was originally identified by the French scientist Louis-Charles Malassez in the late nineteenth century;[7] he associated it with the condition seborrhoeic dermatitis.[8] Raymond Sabouraud identified a dandruff-causing organism in 1904 and called it Pityrosporum Malassezii,[9] honoring Malassez, but at the species level as opposed to the genus level. When it was determined that the organisms were the same, the term "Malassezia" was judged to possess priority.[10]

In the mid-twentieth century, it was reclassified into two species:

- Pityrosporum (Malassezia) ovale, which is lipid-dependent and found only on humans. P. ovale was later divided into two species, P. ovale and P. orbiculare, but current sources consider these terms to refer to a single species of fungus, with M. furfur the preferred name.[11]

- Pityrosporum (Malassezia) pachydermatis, which is lipophilic but not lipid-dependent. It is found on the skin of most animals.

In the mid-1990s, scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, discovered additional species.[12]

Malassezia is the sole genus in the family Malasseziaceae, which was validated by Cvetomir Denchev and Royall T. Moore in 2009.[13] The order Malasseziales had been previously proposed by Moore in 1980,[14] and later emended by Begerow and colleagues in 2000. At this time the order was classified as a member of unknown class placement in the subdivision Ustilaginomycotina.[15] In 2014, Cvetomir and Teodor Denchev circumscribed the class Malasseziomycetes to contain the group.[16]

Description

Malassezia demonstrates a rapid growth rate, typically maturing within 5 days when incubated at temperatures ranging from 30–35 °C (86–95 °F). Growth is less optimal at 25 °C (77 °F), and certain species struggle at 37 °C (99 °F). These organisms can proliferate on media infused with cycloheximide. An essential factor for the growth of Malassezia is the presence of long-chain fatty acids, with M. pachydermatis being an exception. The most conventional cultivation method involves overlaying solid media with a layer of olive oil. However, for nurturing some clinically relevant species, such as the challenging-to-cultivate M. restricta, more intricate culture media may be required. For the most efficient recovery of Malassezia, it has been recommended to collect blood through a lipid infusion catheter and subsequently use lysis-centrifugation—a recommendation backed by multiple comparative studies.[17]

The yeast-like cells of Malassezia, measuring between 1.5–4.5 μm by 3–7 μm, are characterised as phialides featuring tiny collarettes (a small, collar-like flange or lip at the mouth of a phialide from which spores or conidia are produced and released). These collarettes are challenging to identify using standard light microscopes. A defining characteristic of cells from this genus is their morphology: one end is round, while the other has a distinctly blunt termination. This latter end is where singular, broad-based bud-like structures emerge, although in certain species, these structures might be narrower. To effectively visualise the organism's shape, a staining technique involving safranin is recommended, followed by observation under oil immersion. Furthermore, Calcofluor-white staining provides an enhanced clarity of the cell wall and its unique contour. While Malassezia typically lacks hyphal elements, rudimentary forms can sporadically be present.[17]

Species

Species Fungorum accepts 22 species of Malassezia.[18] The following list gives the name of the fungus, the taxonomic authority (those who first described the fungus, or who transferred it into Malassezia from another genus; standardized author abbreviations are used), and the name of the organism from which the fungus was isolated, if not human.

- Malassezia arunalokei Honnavar, Rudramurthy, G.S.Prasad & Chakrabarti[19]

- Malassezia brasiliensis F.J.Cabañes, S.D.A.Coutinho, M.R.Bragulat & G.Castellá[20] – from lesions on the beak of turquoise-fronted amazon parrot

- Malassezia caprae J.Cabañes & Boekhout[21] – from skin of goat

- Malassezia cuniculi J.Cabañes & G.Castellá[22] – from healthy skin of external ear canal of rabbit

- Malassezia dermatis Sugita, M.Takash., A.Nishikawa & Shinoda[23]

- Malassezia equi Nell, S.A.James, C.J.Bond, B.Hunt & Herrtage[24] – from skin of horse

- Malassezia equina J.Cabañes & Boekhout[21] – from skin of horse

- Malassezia furfur (C.P.Robin) Baill.

- Malassezia globosa Midgley, E.Guého & J.Guillot[25]

- Malassezia japonica Sugita, M.Takash., M.Kodama, Tsuboi & A.Nishikawa[26]

- Malassezia muris (Gluge & d'Ukedem ex Guég.) Escomel – skin of mouse

- Malassezia nana A.Hirai, R.Kano, Makimura, H.Yamag. & A.Haseg.[27] – from discharge from ear of cat

- Malassezia obtusa Midgley, J.Guillot & E.Guého[28]

- Malassezia ochoterenai Maecke[29]

- Malassezia pachydermatis (Weidman) C.W.Dodge[30] – from skin of Indian rhinoceros

- Malassezia psittaci F.J.Cabañes, S.D.A.Coutinho, M.R.Bragulat & G.Castellá[31] – from lesions on the beak of blue-headed parrot

- Malassezia restricta E.Guého, J.Guillot & Midgley[32]

- Malassezia slooffiae J.Guillot, Midgley & E.Guého[33] – from skin of pig

- Malassezia sympodialis R.B.Simmons & E.Guého[34]

- Malassezia tropica (Castell.) Schmitter

- Malassezia vespertilionis J.M.Lorch & Vanderwolf[35] – from vesper bats in subfamily Myotinae

- Malassezia yamatoensis Sugita, M.Takash., Tajima, Tsuboi & A.Nishikawa[36]

Role in human diseases

Dermatitis and dandruff

Identification of Malassezia on skin has been aided by the application of molecular or DNA-based techniques. These investigations show that the Malassezia species causing most skin disease in humans, including the most common cause of dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis, is M. globosa (though M. restricta is also involved).[25] The skin rash of tinea versicolor (pityriasis versicolor) is also due to infection by this fungus.

As the fungus requires fat to grow,[12] it is most common in areas with many sebaceous glands: on the scalp,[37] face, and upper part of the body. When the fungus grows too rapidly, the natural renewal of cells is disturbed, and dandruff appears with itching (a similar process may also occur with other fungi or bacteria).

A project in 2007 sequenced the genome of dandruff-causing Malassezia globosa and found it to have 4,285 genes.[38][39] M. globosa uses eight different types of lipase, along with three phospholipases, to break down the oils on the scalp. Any of these 11 proteins would be a suitable target for dandruff medications.

The number of specimens of M. globosa on a human head can be up to ten million.[37]

M. globosa has been predicted to have the ability to reproduce sexually,[40] but this has not been observed.

Research

Malassezia is among the many mycobiota undergoing laboratory research to investigate whether it is associated with types of disease.[41] Translocation of Malassezia spp. from the intestines into pancreatic neoplasms has been associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and the fungi may promote tumor progression through activation of host complement.[42][43]

The yeast M. restricta, normally found in the skin, is linked to disorders like Crohn's disease and inflammatory bowel disease when found in the gut, especially for those with the N12 CARD9 allele, which provokes a stronger inflammatory response to the yeast.[44]

References

- ↑ Baillon, Henri Ernest (1889) (in fr). Traité de botanique médicale cryptogamique. Paris: Octave Doin. p. 234. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5409. OCLC 2139870. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/4328778.

- ↑ "Synonymy: Malassezia Baill., Traité Bot. Méd. Crypt.: 234 (1889)". Species Fungorum. http://www.speciesfungorum.org/Names/SynSpecies.asp?RecordID=8831.

- ↑ Wijayawardene, Nalin; Hyde, Kevin; Al-Ani, Laith Khalil Tawfeeq; Somayeh, Dolatabadi; Stadler, Marc; Haelewaters, Danny et al. (2020). "Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa". Mycosphere 11: 1060–1456. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/8.

- ↑ "Mystery of Jean-Paul Marat’s bathing habit… - The Good Life France" (in en-US). 2021-06-14. https://thegoodlifefrance.com/mystery-of-jean-paul-marats-bathing-habit/.

- ↑ Ran Yuping (2016). "Observation of Fungi, Bacteria, and Parasites in Clinical Skin Samples Using Scanning Electron Microscopy". in Janecek, Milos. Modern Electron Microscopy in Physical and Life Sciences. InTech. doi:10.5772/61850. ISBN 978-953-51-2252-4.

- ↑ Theelen, Bart; Cafarchia, Claudia; Gaitanis, Georgios; Bassukas, Ioannis Dimitrios; Boekhout, Teun; Dawson, Thomas L. (2018). "Malassezia ecology, pathophysiology, and treatment". Medical Mycology 56 (suppl 1): S10–S25. doi:10.1093/mmy/myx134. PMID 29538738.

- ↑ Malassez, L. (1874). "Note sur le champignon du pityriasis simple" (in fr). Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry 2: 451–464.

- ↑ Dawson, Thomas L. (2019). "Malassezia: The Forbidden Kingdom Opens". Cell Host Microbe 25 (3): 345–347. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.010. PMID 30870616.

- ↑ Sabouraud, R. (1904) (in fr). Maladies du cuir chevelu: II. Les maladies desquamatives. Paris: Masson et Cie. p. 646. https://archive.org/details/willan-71517/page/646/mode/2up.

- ↑ "The genus Malassezia and human disease". Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 69 (4): 265–70. 2003. PMID 17642908. http://www.ijdvl.com/article.asp?issn=0378-6323;year=2003;volume=69;issue=4;spage=265;epage=270;aulast=Inamadar.

- ↑ Template:Fitzpatrick 6

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The genus Malassezia with description of four new species". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 69 (4): 337–355. May 1996. doi:10.1007/BF00399623. PMID 8836432.

- ↑ Denchev, C.M.; Moore, R.T. (2009). "Validation of Malasseziaceae and Ceraceosoraceae (Exobasidiomycetes)". Mycotaxon 110: 379–382. doi:10.5248/110.379. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233626547.

- ↑ Moore, R.T. (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina 23 (6): 361–373.

- ↑ Begerow, Dominik; Bauer, Robert; Boekhout, Teun (2000). "Phylogenetic placements of ustilaginomycetous anamorphs as deduced from nuclear LSU rDNA sequences". Mycological Research 104 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1017/s0953756299001161.

- ↑ Denchev, C.M.; Denchev, T.T. (2014). "Nomenclatural novelties". Index Fungorum 145: 1. ISSN 2049-2375. http://www.indexfungorum.org/Publications/Index%20Fungorum%20no.145.pdf.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Larone, Davise Honig (2011). Medically Important Fungi (5th ed.). Washington (D.C.): ASM press. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-55581-660-5.

- ↑ Species Fungorum. "Malassezia". Catalog of Life. https://www.catalogueoflife.org/data/taxon/5KG9.

- ↑ Cabañes, F.J.; Coutinho, S.D.A.; Puig, L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Castellá, G. (2016). "New lipid-dependent Malassezia species from parrots". Revista Iberoamericana de Micología 33 (2): 92–99. doi:10.1016/j.riam.2016.03.003. PMID 27184440.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Two new lipid-dependent Malassezia species from domestic animals". FEMS Yeast Research 7 (6): 1064–1076. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00217.x. ISSN 1567-1356. PMID 17367513.

- ↑ "Malassezia cuniculi sp. nov., a novel yeast species isolated from rabbit skin". Medical Mycology 49 (1): 40–48. 2011. doi:10.3109/13693786.2010.493562. PMID 20560865.

- ↑ "New Yeast Species, Malassezia dermatis, Isolated from Patients with Atopic Dermatitis". J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 (4): 1363–7. April 2002. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.4.1363-1367.2002. PMID 11923357.

- ↑ White, S.D.; Vandenabeele, S.I.J.; Drazenovich, N.L.; Foley, J.E. (2006). "Malassezia species isolated from the intermammary and preputial fossa areas of horses". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 20 (2): 395–398. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[395:MSIFTI2.0.CO;2]. PMID 16594600.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Isolation and expression of a Malassezia globosa lipase gene, LIP1". J. Invest. Dermatol. 127 (9): 2138–46. September 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700844. PMID 17460728.

- ↑ Sugita, Takashi; Masako Takashima; Minako Kodama; Ryoji Tsuboi; Akemi Nishikawa (October 2003). "Description of a New Yeast Species, Malassezia japonica, and Its Detection in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Healthy Subjects". J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 (10): 4695–4699. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.10.4695-4699.2003. PMID 14532205.

- ↑ "Malassezia nana sp. nov., a novel lipid-dependent yeast species isolated from animals". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 (Pt 2): 623–7. March 2004. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02776-0. PMID 15023986.

- ↑ Guého, E.; Midgley, G.; Guillot, J. (1996). "The genus Malassezia with description of four new species". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 69 (4): 337–355. doi:10.1007/BF00399623. PMID 8836432.

- ↑ Maecke, Margarita (1941). "Descripción de una nueva especie de Malassezia: Malassezia ochoterenai, agente causal de Pytiriasis (Tinea) vesicolor y posición sistemática del género Malassezia" (in es). Anales del Instituto de Biología 12: 511–546.

- ↑ "Biotyping of Malassezia pachydermatis strains using the killer system". Rev Iberoam Micol 15 (2): 85–7. June 1998. PMID 17655416.

- ↑ "Malassezia vespertilionis sp. nov. :a new cold-tolerant species of yeast isolated from bats". Persoonia 41: 56–70. 2018. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2018.41.04. PMID 30728599. PMC 6344816. http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/654583.

- ↑ "Genotype analysis of Malassezia restricta as the major cutaneous flora in patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects". Microbiol. Immunol. 48 (10): 755–9. 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03601.x. PMID 15502408.

- ↑ "Malassezia slooffiae-associated dermatitis in a goat". Veterinary Dermatology 18 (5): 348–52. October 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3164.2007.00606.x. PMID 17845623.

- ↑ "Is common neonatal cephalic pustulosis (neonatal acne) triggered by Malassezia sympodialis?". Arch Dermatol 134 (8): 995–8. August 1998. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.8.995. PMID 9722730.

- ↑ Lorch, J.M.; Palmer, J.M.; Vanderwolf, K.J.; Schmidt, K.Z.; Verant, M.L.; Weller, T.J.; Blehert, D.S. (2018). "Malassezia vespertilionis sp. nov.: a new cold-tolerant species of yeast isolated from bats". Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 41 (1): 56–70. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2018.41.04. PMID 30728599.

- ↑ "A new yeast, Malassezia yamatoensis, isolated from a patient with seborrheic dermatitis, and its distribution in patients and healthy subjects". Microbiol. Immunol. 48 (8): 579–83. 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03554.x. PMID 15322337.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Genetic code of dandruff cracked". BBC News (BBC). 2007-11-06. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/7080434.stm.

- ↑ "Dandruff-associated Malassezia genomes reveal convergent and divergent virulence traits shared with plant and human fungal pathogens". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (47): 18730–5. November 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706756104. PMID 18000048. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10418730X.

- ↑ Spectrum Science Public Relations (21 November 2007). "Scientists Complete Genome Sequence Of Fungus Responsible For Dandruff, Skin Disorders" (in en). https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/11/071106101200.htm.

- ↑ "The genus Malassezia: old facts and new concepts". Parassitologia 50 (1–2): 77–9. June 2008. PMID 18693563.

- ↑ "Intestinal mycobiota in health and diseases: from a disrupted equilibrium to clinical opportunities". Microbiome 9 (1): 60. March 2021. doi:10.1186/s40168-021-01024-x. PMID 33715629.

- ↑ "The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL". Nature 574 (7777): 264–267. 2019. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2. PMID 31578522.

- ↑ Loker, Eric S.; Hofkin, Bruce V. (2023). Parasitology: A Conceptual Approach (Second ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 54. doi:10.1201/9780429277405. ISBN 9780429277405.

- ↑ Jose J. Limon, Jie Tang, Dalin Li, Andrea J. Wolf, Kathrin S. Michelsen, Vince Funari, Matthew Gargus, Christopher Nguyen, Purnima Sharma, Viviana I. Maymi, Iliyan D. Iliev, Joseph H. Skalski, Jordan Brown, Carol Landers, James Borneman, Jonathan Braun, Stephan R. Targan, Dermot P.B. McGovern, David M. Underhill, Malassezia Is Associated with Crohn’s Disease and Exacerbates Colitis in Mouse Models, Cell Host & Microbe, Volume 25, Issue 3, 2019, Pages 377-388.e6, ISSN 1931-3128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.007. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1931312819300459)

Further reading

- Shams Ghahfarokhi, M.; Razzaghi Abyaneh, M. (4 October 2015). "Rapid Identification of Malassezia furfur from other Malassezia Species: A Major Causative Agent of Pityriasis Versicolor". Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences 29 (1): 36–39. http://ijms.sums.ac.ir/article_40115.html.

Wikidata ☰ Q14488912 entry

|