Correlation function

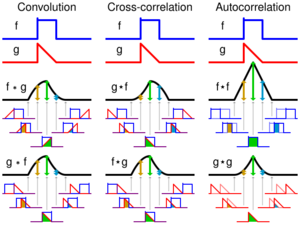

A correlation function is a function that gives the statistical correlation between random variables, contingent on the spatial or temporal distance between those variables.[1] If one considers the correlation function between random variables representing the same quantity measured at two different points, then this is often referred to as an autocorrelation function, which is made up of autocorrelations. Correlation functions of different random variables are sometimes called cross-correlation functions to emphasize that different variables are being considered and because they are made up of cross-correlations.

Correlation functions are a useful indicator of dependencies as a function of distance in time or space, and they can be used to assess the distance required between sample points for the values to be effectively uncorrelated. In addition, they can form the basis of rules for interpolating values at points for which there are no observations.

Correlation functions used in astronomy, financial analysis, econometrics, and statistical mechanics differ only in the particular stochastic processes they are applied to. In quantum field theory there are correlation functions over quantum distributions.

Definition

For possibly distinct random variables X(s) and Y(t) at different points s and t of some space, the correlation function is

where is described in the article on correlation. In this definition, it has been assumed that the stochastic variables are scalar-valued. If they are not, then more complicated correlation functions can be defined. For example, if X(s) is a random vector with n elements and Y(t) is a vector with q elements, then an n×q matrix of correlation functions is defined with element

When n=q, sometimes the trace of this matrix is focused on. If the probability distributions have any target space symmetries, i.e. symmetries in the value space of the stochastic variable (also called internal symmetries), then the correlation matrix will have induced symmetries. Similarly, if there are symmetries of the space (or time) domain in which the random variables exist (also called spacetime symmetries), then the correlation function will have corresponding space or time symmetries. Examples of important spacetime symmetries are —

- translational symmetry yields C(s,s') = C(s − s') where s and s' are to be interpreted as vectors giving coordinates of the points

- rotational symmetry in addition to the above gives C(s, s') = C(|s − s'|) where |x| denotes the norm of the vector x (for actual rotations this is the Euclidean or 2-norm).

Higher order correlation functions are often defined. A typical correlation function of order n is (the angle brackets represent the expectation value)

If the random vector has only one component variable, then the indices are redundant. If there are symmetries, then the correlation function can be broken up into irreducible representations of the symmetries — both internal and spacetime.

Properties of probability distributions

With these definitions, the study of correlation functions is similar to the study of probability distributions. Many stochastic processes can be completely characterized by their correlation functions; the most notable example is the class of Gaussian processes.

Probability distributions defined on a finite number of points can always be normalized, but when these are defined over continuous spaces, then extra care is called for. The study of such distributions started with the study of random walks and led to the notion of the Itō calculus.

The Feynman path integral in Euclidean space generalizes this to other problems of interest to statistical mechanics. Any probability distribution which obeys a condition on correlation functions called reflection positivity leads to a local quantum field theory after Wick rotation to Minkowski spacetime (see Osterwalder-Schrader axioms). The operation of renormalization is a specified set of mappings from the space of probability distributions to itself. A quantum field theory is called renormalizable if this mapping has a fixed point which gives a quantum field theory.

See also

- Autocorrelation

- Correlation does not imply causation

- Correlogram

- Covariance function

- Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient

- Correlation function

- Correlation function (statistical mechanics)

- Correlation function (quantum field theory)

- Mutual information

- Rate distortion theory

- Radial distribution function

References

- ↑ Pal, Manoranjan; Bharati, Premananda (2019). "Introduction to Correlation and Linear Regression Analysis". Applications of Regression Techniques. Springer, Singapore. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9314-3_1. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-9314-3_1. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

|