Biology:Timeline of the evolutionary history of life

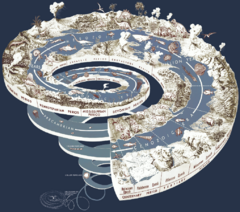

The timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory outlining the major events during the development of life on planet Earth. Dates in this article are consensus estimates based on scientific evidence, mainly fossils.

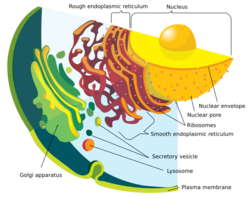

In biology, evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organization, from kingdoms to species, and individual organisms and molecules, such as DNA and proteins. The similarities between all present day organisms imply a common ancestor from which all known species, living and extinct, have diverged. More than 99 percent of all species that ever lived (over five billion)[1] are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[4] with about 1.2 million or 14% documented, the rest not yet described.[5] However, a 2016 report estimates an additional 1 trillion microbial species, with only 0.001% described.[6]

There has been controversy between more traditional views of steadily increasing biodiversity, and a newer view of cycles of annihilation and diversification, so that certain past times, such as the Cambrian explosion, experienced maximums of diversity followed by sharp winnowing.[7][8]

Extinction

Species go extinct constantly as environments change, as organisms compete for environmental niches, and as genetic mutation leads to the rise of new species from older ones. At long irregular intervals, Earth's biosphere suffers a catastrophic die-off, a mass extinction,[9] often comprising an accumulation of smaller extinction events over a relatively brief period.[10]

The first known mass extinction was the Great Oxidation Event 2.4 billion years ago, which killed most of the planet's obligate anaerobes. Researchers have identified five other major extinction events in Earth's history, with estimated losses below:[11]

- End Ordovician: 440 million years ago, 86% of all species lost, including graptolites

- Late Devonian: 375 million years ago, 75% of species lost, including most trilobites

- End Permian, The Great Dying: 251 million years ago, 96% of species lost, including tabulate corals, and most trees and synapsids

- End Triassic: 200 million years ago, 80% of species lost, including all conodonts

- End Cretaceous: 66 million years ago, 76% of species lost, including all ammonites, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and nonavian dinosaurs

Smaller extinction events have occurred in the periods between, with some dividing geologic time periods and epochs. The Holocene extinction event is currently under way.[12]

Factors in mass extinctions include continental drift, changes in atmospheric and marine chemistry, volcanism and other aspects of mountain formation, changes in glaciation, changes in sea level, and impact events.[10]

Detailed timeline

In this timeline, Ma (for megaannum) means "million years ago," ka (for kiloannum) means "thousand years ago," and ya means "years ago."

Hadean Eon

4540 Ma – 4000 Ma

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 4540 Ma | Planet Earth forms from the accretion disc revolving around the young Sun, perhaps preceded by formation of organic compounds necessary for life in the surrounding protoplanetary disk of cosmic dust.[13][14] |

| 4510 Ma | |

| 4404 Ma | Evidence of the first liquid water on Earth which were found in the oldest known zircon crystals.[15] |

| 4280–3770 Ma

</ref>[16] |

Archean Eon

4000 Ma – 2500 Ma

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 4100 Ma | Earliest possible preservation of biogenic carbon.[17][18] |

| 4100–3800 Ma | Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB): extended barrage by meteoroids impacting the inner planets. Thermal flux from widespread hydrothermal activity during the LHB may have aided abiogenesis and life's early diversification.[19] Possible remains of biotic life were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.[20][21] Probable origin of life. |

| 4000 Ma | Formation of a greenstone belt of the Acasta Gneiss of the Slave craton in northwest Canada - the oldest known rock belt.[22] |

| 3900–2500 Ma | |

| 3800 Ma | |

| 3800–3500 Ma

Bacteria develop primitive photosynthesis, which at first did not produce oxygen.[23] These organisms exploit a proton gradient to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a mechanism used by virtually all subsequent organisms.[24][25][26] | |

| 3000 Ma | Photosynthesizing cyanobacteria using water as a reducing agent and producing oxygen as a waste product.[27] Free oxygen initially oxidizes dissolved iron in the oceans, creating iron ore. Oxygen concentration in the atmosphere slowly rises, poisoning many bacteria and eventually triggering the Great Oxygenation Event. |

| 2800 Ma | Oldest evidence for microbial life on land in the form of organic matter-rich paleosols, ephemeral ponds and alluvial sequences, some bearing microfossils.[28] |

Proterozoic Eon

2500 Ma – 539 Ma. Contains the Palaeoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic eras.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 2500 Ma | Great Oxidation Event led by cyanobacteria's oxygenic photosynthesis.[27] Commencement of plate tectonics with old marine crust dense enough to subduct.[22] |

| 2023 Ma | Formation of the Vredefort impact structure, one of the largest and oldest verified impact structures on Earth. The crater is estimated to have been between 170–300 kilometres (110–190 mi) across when it first formed.[29] |

| By 1850 Ma | |

| 1500 Ma | Volyn biota, a collection of exceptionally well-preserved microfossils with varying morphologies.[30] |

| 1300 Ma | Earliest land fungi.[31] |

| By 1200 Ma | Meiosis and sexual reproduction in single-celled eukaryotes, possibly even in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes[32] or in the RNA world.[33] Sexual reproduction may have increased the rate of evolution.[34] |

| By 1000 Ma | First non-marine eukaryotes move onto land. They were photosynthetic and multicellular, indicating that plants evolved much earlier than originally thought.[35] |

| 750 Ma | |

| 720–630 Ma | |

| 600 Ma | Accumulation of atmospheric oxygen allows the formation of an ozone layer.[36] Previous land-based life would probably have required other chemicals to attenuate ultraviolet radiation.[28] |

| 580–542 Ma | Ediacaran biota, the first large, complex aquatic multicellular organisms.[37] |

| 580–500 Ma | Cambrian explosion: most modern animal phyla appear.[38][39] |

| 550–540 Ma | Ctenophora (comb jellies),[40] Porifera (sponges),[41] Anthozoa (corals and sea anemones),[42] Ikaria wariootia (an early Bilaterian).[43] |

Phanerozoic Eon

539 Ma – present

The Phanerozoic Eon (Greek: period of well-displayed life) marks the appearance in the fossil record of abundant, shell-forming and/or trace-making organisms. It is subdivided into three eras, the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, with major mass extinctions at division points.

Palaeozoic Era

538.8 Ma – 251.9 Ma and contains the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian periods.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 535 Ma | Major diversification of living things in the oceans: arthropods (e.g. trilobites, crustaceans), chordates, echinoderms, molluscs, brachiopods, foraminifers and radiolarians, etc. |

| 530 Ma | The first known footprints on land date to 530 Ma.[47] |

| 520 Ma | Earliest graptolites.[48] |

| 511 Ma | Earliest crustaceans.[49] |

| 505 Ma | Fossilization of the Burgess Shale |

| 500 Ma | Jellyfish have existed since at least this time. |

| 485 Ma | First vertebrates with true bones (jawless fishes). |

| 450 Ma | First complete conodonts and echinoids appear. |

| 440 Ma | First agnathan fishes: Heterostraci, Galeaspida, and Pituriaspida. |

| 420 Ma | Earliest ray-finned fishes, trigonotarbid arachnids, and land scorpions.[50] |

| 410 Ma | First signs of teeth in fish. Earliest Nautilida, lycophytes, and trimerophytes. |

| 488–400 Ma | First cephalopods (nautiloids)[51] and chitons.[52] |

| 395 Ma | First lichens, stoneworts. Earliest harvestmen, mites, hexapods (springtails) and ammonoids. The earliest known tracks on land named the Zachelmie trackways which are possibly related to icthyostegalians.[53] |

| 375 Ma | Tiktaalik, a lobe-finned fish with some anatomical features similar to early tetrapods. It has been suggested to be a transitional species between fish and tetrapods.[54] |

| 365 Ma | Acanthostega is one of the earliest vertebrates capable of walking.[55] |

| 363 Ma | By the start of the Carboniferous Period, the Earth begins to resemble its present state. Insects roamed the land and would soon take to the skies; sharks swam the oceans as top predators,[56] and vegetation covered the land, with seed-bearing plants and forests soon to flourish.

Four-limbed tetrapods gradually gain adaptations which will help them occupy a terrestrial life-habit. |

| 360 Ma | First crabs and ferns. Land flora dominated by seed ferns. The Xinhang forest grows around this time.[57] |

| 350 Ma | First large sharks, ratfishes, and hagfish; first crown tetrapods (with five digits and no fins and scales). |

| 350 Ma | Diversification of amphibians.[58] |

| 325-335 Ma | First Reptiliomorpha.[59] |

| 330-320 Ma | First amniote vertebrates (Paleothyris).[60] |

| 320 Ma | Synapsids (precursors to mammals) separate from sauropsids (reptiles) in late Carboniferous.[61] |

| 305 Ma | The Carboniferous rainforest collapse occurs, causing a minor extinction event, as well as paving the way for amniotes to become dominant over amphibians and seed plants over ferns and lycophytes.

First diapsid reptiles (e.g. Petrolacosaurus). |

| 280 Ma | Earliest beetles, seed plants and conifers diversify while lepidodendrids and sphenopsids decrease. Terrestrial temnospondyl amphibians and pelycosaurs (e.g. Dimetrodon) diversify in species. |

| 275 Ma | Therapsid synapsids separate from pelycosaur synapsids. |

| 265 Ma | Gorgonopsians appear in the fossil record.[62] |

| 251.9–251.4 Ma |

Mesozoic Era

From 251.9 Ma to 66 Ma and containing the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 250 Ma | Mesozoic marine revolution begins: increasingly well adapted and diverse predators stress sessile marine groups; the "balance of power" in the oceans shifts dramatically as some groups of prey adapt more rapidly and effectively than others. |

| 250 Ma | Triadobatrachus massinoti is the earliest known frog. |

| 248 Ma | Sturgeon and paddlefish (Acipenseridae) first appear. |

| 245 Ma | Earliest ichthyosaurs |

| 240 Ma | Increase in diversity of cynodonts and rhynchosaurs |

| 225 Ma | Earliest dinosaurs (prosauropods), first cardiid bivalves, diversity in cycads, bennettitaleans, and conifers. First teleost fishes. First mammals (Adelobasileus). |

| 220 Ma | Seed-producing Gymnosperm forests dominate the land; herbivores grow to huge sizes to accommodate the large guts necessary to digest the nutrient-poor plants.[citation needed] First flies and turtles (Odontochelys). First coelophysoid dinosaurs. First mammals from small-sized cynodonts, which transitioned towards a nocturnal, insectivorous, and endothermic lifestyle. |

| 205 Ma | Massive Triassic/Jurassic extinction. It wipes out all pseudosuchians except crocodylomorphs, who transitioned to an aquatic habitat, while dinosaurs took over the land and pterosaurs filled the air. |

| 200 Ma | First accepted evidence for viruses infecting eukaryotic cells (the group Geminiviridae).[63] However, viruses are still poorly understood and may have arisen before "life" itself, or may be a more recent phenomenon.

Major extinctions in terrestrial vertebrates and large amphibians. Earliest examples of armoured dinosaurs. |

| 195 Ma | First pterosaurs with specialized feeding (Dorygnathus). First sauropod dinosaurs. Diversification in small, ornithischian dinosaurs: heterodontosaurids, fabrosaurids, and scelidosaurids. |

| 190 Ma | Pliosauroids appear in the fossil record. First lepidopteran insects (Archaeolepis), hermit crabs, modern starfish, irregular echinoids, corbulid bivalves, and tubulipore bryozoans. Extensive development of sponge reefs. |

| 176 Ma | First Stegosaurian dinosaurs. |

| 170 Ma | Earliest salamanders, newts, cryptoclidids, elasmosaurid plesiosaurs, and cladotherian mammals. Sauropod dinosaurs diversify. |

| 168 Ma | First lizards. |

| 165 Ma | First rays and glycymeridid bivalves. First vampire squids.[64] |

| 163 Ma | Pterodactyloid pterosaurs first appear.[65] |

| 161 Ma | Ceratopsian dinosaurs appear in the fossil record (Yinlong) and the oldest known eutherian mammal: Juramaia. |

| 160 Ma | Multituberculate mammals (genus Rugosodon) appear in eastern China . |

| 155 Ma | First blood-sucking insects (ceratopogonids), rudist bivalves, and cheilostome bryozoans. Archaeopteryx, a possible ancestor to the birds, appears in the fossil record, along with triconodontid and symmetrodont mammals. Diversity in stegosaurian and theropod dinosaurs. |

| 131 Ma | First pine trees. |

| 140 Ma | Orb-weaver spiders appear. |

| 135 Ma | Rise of the angiosperms. Some of these flowering plants bear structures that attract insects and other animals to spread pollen; other angiosperms are pollinated by wind or water. This innovation causes a major burst of animal coevolution. First freshwater pelomedusid turtles. Earliest krill. |

| 120 Ma | Oldest fossils of heterokonts, including both marine diatoms and silicoflagellates. |

| 115 Ma | First monotreme mammals. |

| 114 Ma | Earliest bees.[66] |

| 112 Ma | Xiphactinus, a large predatory fish, appears in the fossil record. |

| 110 Ma | First hesperornithes, toothed diving birds. Earliest limopsid, verticordiid, and thyasirid bivalves. |

| 100 Ma | First ants.[67] |

| 100–95 Ma | Spinosaurus, the largest theropod dinosaur, appears in the fossil record.[68] |

| 95 Ma | First crocodilians evolve.[69] |

| 90 Ma | Extinction of ichthyosaurs. Earliest snakes and nuculanid bivalves. Large diversification in angiosperms: magnoliids, rosids, hamamelidids, monocots, and ginger. Earliest examples of ticks. Probable origins of placental mammals (earliest undisputed fossil evidence is 66 Ma). |

| 86–76 Ma | Diversification of therian mammals.[70][71] |

| 70 Ma | Multituberculate mammals increase in diversity. First yoldiid bivalves. First possible ungulates (Protungulatum). |

| 68–66 Ma | Tyrannosaurus, the largest terrestrial predator of western North America, appears in the fossil record. First species of Triceratops.[72] |

Cenozoic Era

66 Ma – present

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 66 Ma | |

| 66 Ma- | Rapid dominance of conifers and ginkgos in high latitudes, along with mammals becoming the dominant species. First psammobiid bivalves. Earliest rodents. Rapid diversification in ants. |

| 63 Ma | Evolution of the creodonts, an important group of meat-eating (carnivorous) mammals. |

| 62 Ma | Evolution of the first penguins. |

| 60 Ma | Diversification of large, flightless birds. Earliest true primates,[who?] along with the first semelid bivalves, edentate, carnivoran and lipotyphlan mammals, and owls. The ancestors of the carnivorous mammals (miacids) were alive.[citation needed] |

| 59 Ma | Earliest sailfish appear. |

| 56 Ma | Gastornis, a large flightless bird, appears in the fossil record. |

| 55 Ma | Modern bird groups diversify (first song birds, parrots, loons, swifts, woodpeckers), first whale (Himalayacetus), earliest lagomorphs, armadillos, appearance of sirenian, proboscidean mammals in the fossil record. Flowering plants continue to diversify. The ancestor (according to theory) of the species in the genus Carcharodon, the early mako shark Isurus hastalis, is alive. Ungulates split into artiodactyla and perissodactyla, with some members of the former returning to the sea. |

| 52 Ma | First bats appear (Onychonycteris). |

| 50 Ma | Peak diversity of dinoflagellates and nannofossils, increase in diversity of anomalodesmatan and heteroconch bivalves, brontotheres, tapirs, rhinoceroses, and camels appear in the fossil record, diversification of primates. |

| 40 Ma | Modern-type butterflies and moths appear. Extinction of Gastornis. Basilosaurus, one of the first of the giant whales, appeared in the fossil record. |

| 38 Ma | Earliest bears. |

| 37 Ma | First nimravid ("false saber-toothed cats") carnivores — these species are unrelated to modern-type felines. First alligators and ruminants. |

| 35 Ma | Grasses diversify from among the monocot angiosperms; grasslands begin to expand. Slight increase in diversity of cold-tolerant ostracods and foraminifers, along with major extinctions of gastropods, reptiles, amphibians, and multituberculate mammals. Many modern mammal groups begin to appear: first glyptodonts, ground sloths, canids, peccaries, and the first eagles and hawks. Diversity in toothed and baleen whales. |

| 33 Ma | Evolution of the thylacinid marsupials (Badjcinus). |

| 30 Ma | First balanids and eucalypts, extinction of embrithopod and brontothere mammals, earliest pigs and cats. |

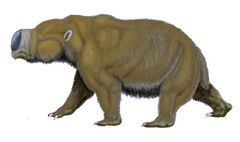

| 28 Ma | Paraceratherium appears in the fossil record, the largest terrestrial mammal that ever lived. First pelicans. |

| 25 Ma | Pelagornis sandersi appears in the fossil record, the largest flying bird that ever lived. |

| 25 Ma | First deer. |

| 24 Ma | First pinnipeds. |

| 23 Ma | Earliest ostriches, trees representative of most major groups of oaks have appeared by now.[73] |

| 20 Ma | First giraffes, hyenas, and giant anteaters, increase in bird diversity. |

| 17 Ma | First birds of the genus Corvus (crows). |

| 15 Ma | Genus Mammut appears in the fossil record, first bovids and kangaroos, diversity in Australian megafauna. |

| 10 Ma | Grasslands and savannas are established, diversity in insects, especially ants and termites, horses increase in body size and develop high-crowned teeth, major diversification in grassland mammals and snakes. |

| 9.5 Ma [dubious ] | Great American Interchange, where various land and freshwater faunas migrated between North and South America. Armadillos, opossums, hummingbirds Phorusrhacids, Ground Sloths, Glyptodonts, and Meridiungulates traveled to North America, while horses, tapirs, saber-toothed cats, jaguars, bears, coaties, ferrets, otters, skunks and deer entered South America. |

| 9 Ma | First platypuses. |

| 6.5 Ma | First hominins (Sahelanthropus). |

| 6 Ma | Australopithecines diversify (Orrorin, Ardipithecus). |

| 5 Ma | First tree sloths and hippopotami, diversification of grazing herbivores like zebras and elephants, large carnivorous mammals like lions and the genus Canis, burrowing rodents, kangaroos, birds, and small carnivores, vultures increase in size, decrease in the number of perissodactyl mammals. Extinction of nimravid carnivores. First leopard seals. |

| 4.8 Ma | Mammoths appear in the fossil record. |

| 4.5 Ma | Marine iguanas diverge from land iguanas. |

| 4 Ma | Australopithecus evolves. Stupendemys appears in the fossil record as the largest freshwater turtle, first modern elephants, giraffes, zebras, lions, rhinoceros and gazelles appear in the fossil record |

| 3.6 Ma | Blue whales grow to modern size. |

| 3 Ma | Earliest swordfish. |

| 2.7 Ma | Paranthropus evolves. |

| 2.5 Ma | Earliest species of Arctodus and Smilodon evolve. |

| 2 Ma | First members of genus Homo, Homo Habilis, appear in the fossil record. Diversification of conifers in high latitudes. The eventual ancestor of cattle, aurochs (Bos primigenus), evolves in India. |

| 1.7 Ma | Australopithecines go extinct. |

| 1.2 Ma | Evolution of Homo antecessor. The last members of Paranthropus die out. |

| 1 Ma | First coyotes. |

| 600 ka | Evolution of Homo heidelbergensis. |

| 400 ka | First polar bears. |

| 350 ka | Evolution of Neanderthals. |

| 300 ka | Gigantopithecus, a giant relative of the orangutan from Asia dies out. |

| 250 ka | |

| 70 ka | Genetic bottleneck in humans (Toba catastrophe theory). |

| 40 ka | Last giant monitor lizards (Varanus priscus) die out. |

| 35-25 ka | Extinction of Neanderthals. Domestication of dogs. |

| 15 ka | Last woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are believed to have gone extinct. |

| 11 ka | Short-faced bears vanish from North America, with the last giant ground sloths dying out. All Equidae become extinct in North America. Domestication of various ungulates. |

| 10 ka | Holocene epoch starts[74] after the Last Glacial Maximum. Last mainland species of woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenus) die out, as does the last Smilodon species. |

| 8 ka | The Giant Lemur dies out. |

See also

- Evolutionary history of plants (timeline)

- Geologic time scale

- History of Earth

- Sociocultural evolution

- Timeline of human evolution

References

- ↑ McKinney 1997, p. 110

- ↑ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, S. C.; Stearns, Stephen C. (2000). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. p. preface x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=0BHeC-tXIB4C&q=99%20percent. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Novacek, Michael J. (November 8, 2014). "Prehistory's Brilliant Future". The New York Times (New York). ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/09/opinion/sunday/prehistorys-brilliant-future.html.

- ↑ Miller & Spoolman 2012, p. 62

- ↑ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina et al. (August 23, 2011). "How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?". PLOS Biology 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. ISSN 1545-7885. PMID 21886479.

- ↑ Staff (2 May 2016). "Researchers find that Earth may be home to 1 trillion species". National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=138446.

- ↑ Hickman, Crystal; Starn, Autumn. "The Burgess Shale & Models of Evolution". Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University. http://www.as.wvu.edu/~kgarbutt/EvolutionPage/Studentsites/Burgesspages/models_of_evolution.html.

- ↑ Barton et al. 2007, Figure 10.20 Four diagrams of evolutionary models

- ↑ "Measuring the sixth mass extinction - Cosmos". https://cosmosmagazine.com/palaeontology/measuring-sixth-mass-extinction.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "History of life on Earth". https://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/history_of_the_earth.

- ↑ "The big five mass extinctions - Cosmos". 5 July 2015. https://cosmosmagazine.com/palaeontology/big-five-extinctions.

- ↑ "The biotic crisis and the future of evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (1): 5389–5392. doi:10.1073/pnas.091092498. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 11344283. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...98.5389M.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Clara (March 29, 2012). "Life's Building Blocks May Have Formed in Dust Around Young Sun". Space.com (Salt Lake City, UT: Purch). http://www.space.com/15089-life-building-blocks-young-sun-dust.html.

- ↑ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved" (in en). Geological Society, London, Special Publications 190 (1): 205–221. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.2001.190.01.14. Bibcode: 2001GSLSP.190..205D. https://www.lyellcollection.org/doi/10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ↑ Wilde, Simon A.; Valley, John W.; Peck, William H.; Graham, Colin M. (January 11, 2001). "Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago" (in en). Nature 409 (6817): 175–178. doi:10.1038/35051550. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11196637. https://websites.pmc.ucsc.edu/~pkoch/EART_206/09-0113/Wilde%20et%2001%20Nature%20409-175.pdf.

- ↑ Dunham, Will (1 March 2017). "Canadian bacteria-like fossils called oldest evidence of life". Reuters. http://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/idCAKBN16858B?sp=true.

- ↑ "4.1-billion-year-old crystal may hold earliest signs of life" (in en-US). 2015-10-19. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/41-billion-year-old-crystal-may-hold-earliest-signs-life.

- ↑ Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnke, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; Mao, Wendy L. (2015-11-24). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (47): 14518–14521. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 26483481. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11214518B.

- ↑ Abramov, Oleg; Mojzsis, Stephen J. (May 21, 2009). "Microbial habitability of the Hadean Earth during the late heavy bombardment". Nature 459 (7245): 419–422. doi:10.1038/nature08015. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19458721. Bibcode: 2009Natur.459..419A. http://isotope.colorado.edu/2009_Abramov_Mojzsis_Nature.pdf. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (October 19, 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Excite. Associated Press (Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network). http://apnews.excite.com/article/20151019/us-sci--earliest_life-a400435d0d.html.

- ↑ Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnike, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark et al. (November 24, 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (47): 14518–14521. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 26483481. PMC 4664351. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11214518B. http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/14/1517557112.full.pdf. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bjornerud 2005

- ↑ Olson, John M. (May 2006). "Photosynthesis in the Archean era". Photosynthesis Research 88 (2): 109–117. doi:10.1007/s11120-006-9040-5. ISSN 0166-8595. PMID 16453059. Bibcode: 2006PhoRe..88..109O.

- ↑ "Proton Gradient, Cell Origin, ATP Synthase - Learn Science at Scitable". http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/why-are-cells-powered-by-proton-gradients-14373960.

- ↑ Romano, Antonio H.; Conway, Tyrrell (July–September 1996). "Evolution of carbohydrate metabolic pathways". Research in Microbiology 147 (6–7): 448–455. doi:10.1016/0923-2508(96)83998-2. ISSN 0923-2508. PMID 9084754.

- ↑ Knowles, Jeremy R. (July 1980). "Enzyme-Catalyzed Phosphoryl Transfer Reactions". Annual Review of Biochemistry 49: 877–919. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 6250450.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Buick, Roger (August 27, 2008). "When did oxygenic photosynthesis evolve?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 363 (1504): 2731–2743. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0041. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 18468984.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Beraldi-Campesi, Hugo (February 23, 2013). "Early life on land and the first terrestrial ecosystems". Ecological Processes 2 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2192-1709-2-1. ISSN 2192-1709. Bibcode: 2013EcoPr...2....1B. http://www.ecologicalprocesses.com/content/pdf/2192-1709-2-1.pdf.

- ↑ Huber, M. S.; Kovaleva, E.; Rae, A. S. P; Tisato, N.; Gulick, S. P. S (August 2023). "Can Archean Impact Structures Be Discovered? A Case Study From Earth's Largest, Most Deeply Eroded Impact Structure". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 128 (8). doi:10.1029/2022JE007721. ISSN 2169-9097. Bibcode: 2023JGRE..12807721H.

- ↑ Franz G., Lyckberg P., Khomenko V., Chournousenko V., Schulz H.-M., Mahlstedt N., Wirth R., Glodny J., Gernert U., Nissen J. (2022). "Fossilization of Precambrian microfossils in the Volyn pegmatite, Ukraine". Biogeosciences 19 (6): 1795–1811. doi:10.5194/bg-19-1795-2022. Bibcode: 2022BGeo...19.1795F. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/19/1795/2022/bg-19-1795-2022.pdf.

- ↑ "First Land Plants and Fungi Changed Earth's Climate, Paving the Way for Explosive Evolution of Land Animals, New Gene Study Suggests". science.psu.edu. http://science.psu.edu/news-and-events/2001-news/Hedges8-2001.htm. "The researchers found that land plants had evolved on Earth by about 700 million years ago and land fungi by about 1,300 million years ago — much earlier than previous estimates of around 480 million years ago, which were based on the earliest fossils of those organisms."

- ↑ Bernstein, Bernstein & Michod 2012, pp. 1–50

- ↑ Bernstein, Harris; Byerly, Henry C.; Hopf, Frederic A.; Michod, Richard E. (October 7, 1984). "Origin of sex". Journal of Theoretical Biology 110 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80178-2. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 6209512. Bibcode: 1984JThBi.110..323B.

- ↑ Butterfield, Nicholas J. (Summer 2000). "Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes". Paleobiology 26 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/content/26/3/386.abstract.

- ↑ Strother, Paul K.; Battison, Leila; Brasier, Martin D.; Wellman, Charles H. (26 May 2011). "Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes". Nature 473 (7348): 505–509. doi:10.1038/nature09943. PMID 21490597. Bibcode: 2011Natur.473..505S.

- ↑ "Formation of the Ozone Layer". Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center. NASA. September 9, 2009. http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/ozone/additional/science-focus/about-ozone/ozone_formation.shtml.

- ↑ Narbonne, Guy (January 2008). "The Origin and Early Evolution of Animals". Kingston, Ontario, Canada: Queen's University. http://geol.queensu.ca/people/narbonne/recent_pubs1.html.

- ↑ Waggoner, Ben M.; Collins, Allen G.; Hsu, Karen; Kang, Myun; Lavarias, Amy; Prabaker, Kavitha; Skaggs, Cody (November 22, 1994). "The Cambrian Period". in Rieboldt, Sarah; Smith, Dave. Berkeley, CA: University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cambrian/cambrian.php.

- ↑ Lane, Abby (January 20, 1999). "Timing". Bristol, England: University of Bristol. http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/Palaeofiles/Cambrian/timing/timing.html.

- ↑ Chen, Jun-Yuan; Schopf, J. William; Bottjer, David J.; Zhang, Chen-Yu; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Tripathi, Abhishek B.; Wang, Xiu-Qiang; Yang, Yong-Hua et al. (2007-04-10). "Raman spectra of a Lower Cambrian ctenophore embryo from southwestern Shaanxi, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (15): 6289–6292. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701246104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 17404242. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.6289C.

- ↑ Müller, W. E. G.; Jinhe Li; Schröder, H. C.; Li Qiao; Xiaohong Wang (2007-05-03). "The unique skeleton of siliceous sponges (Porifera; Hexactinellida and Demospongiae) that evolved first from the Urmetazoa during the Proterozoic: a review" (in English). Biogeosciences 4 (2): 219–232. doi:10.5194/bg-4-219-2007. ISSN 1726-4170. Bibcode: 2007BGeo....4..219M. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/4/219/2007/.

- ↑ "Corals and sea anemones (anthozoa)" (in en). 2018-12-11. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/corals-and-sea-anemones-anthozoa.

- ↑ Grazhdankin, Dima (February 8, 2016). "Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: facies versus biogeography and evolution" (in en). Paleobiology 30 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0203:PODITE>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/paleobiology/article/abs/patterns-of-distribution-in-the-ediacaran-biotas-facies-versus-biogeography-and-evolution/E1A8C6052128EB081CB260731B5628A6.

- ↑ Lindgren, A.R.; Giribet, G.; Nishiguchi, M.K. (2004). "A combined approach to the phylogeny of Cephalopoda (Mollusca)". Cladistics 20 (5): 454–486. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00032.x. PMID 34892953. http://faculty.uml.edu/rhochberg/hochberglab/Courses/InvertZool/Cephalopod%20phylogeny.pdf.

- ↑ "Palaeos Paleozoic: Cambrian: The Cambrian Period - 2". http://www.palaeos.com/Paleozoic/Cambrian/Cambrian.2.html.

- ↑ "Pteridopsida: Fossil Record". University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/plants/pterophyta/pteridofr.html.

- ↑ Clarke, Tom (April 30, 2002). "Oldest fossil footprints on land". Nature. doi:10.1038/news020429-2. ISSN 1744-7933. http://www.nature.com/news/2002/020430/full/news020429-2.html. Retrieved 2015-03-09. "The oldest fossils of footprints ever found on land hint that animals may have beaten plants out of the primordial seas. Lobster-sized, centipede-like animals made the prints wading out of the ocean and scuttling over sand dunes about 530 million years ago. Previous fossils indicated that animals didn't take this step until 40 million years later.".

- ↑ "Graptolites" (in en-GB). https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/fossils-and-geological-time/graptolites/.

- ↑ Leutwyler, Kristin. "511-Million-Year-Old Fossil Suggests Pre-Cambrian Origins for Crustaceans" (in en). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/511-million-year-old-foss/.

- ↑ Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (September 2011). "Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Uncertainty". Evolution: Education and Outreach 4 (3): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y. ISSN 1936-6426.

- ↑ Landing, Ed; Westrop, Stephen R. (September 1, 2006). [958:LOFSAS2.0.CO;2.full "Lower Ordovician Faunas, Stratigraphy, and Sea-Level History of the Middle Beekmantown Group, Northeastern New York"]. Journal of Paleontology 80 (5): 958–980. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[958:LOFSAS2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0022-3360. https://bioone.org/journals/journal-of-paleontology/volume-80/issue-5/0022-3360_2006_80_958_LOFSAS_2.0.CO_2/LOWER-ORDOVICIAN-FAUNAS-STRATIGRAPHY-AND-SEA-LEVEL-HISTORY-OF-THE/10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[958:LOFSAS]2.0.CO;2.full.

- ↑ Serb, Jeanne M.; Eernisse, Douglas J. (September 25, 2008). "Charting Evolution's Trajectory: Using Molluscan Eye Diversity to Understand Parallel and Convergent Evolution" (in en). Evolution: Education and Outreach 1 (4): 439–447. doi:10.1007/s12052-008-0084-1. ISSN 1936-6434.

- ↑ Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Szrek, Piotr; Narkiewicz, Katarzyna; Narkiewicz, Marek; Ahlberg, Per E. (January 1, 2010). "Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland" (in en). Nature 463 (7277): 43–48. doi:10.1038/nature08623. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 20054388. Bibcode: 2010Natur.463...43N. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/46752909/trackways-with-cover-page-v2.pdf?Expires=1664076708&Signature=T90exV-98rO1WUlSoLdNXTzzvqxsI-rCpzhxd1xC6Pt2wc-hH2xVdXEP57MFHFhPw5yfMK9kf5bRJ6WTM1WH-jXOTPfHoKUJVPH-s50O0~h6F0yg1HemExF546SgHoUEJ4a-HVpyzB2IXHNB8atvNjpfHTburCWCtaN8h4-Axs8yadT5uS8rNSgBgOZeXYJdHYk9D3FZ3vuEUC44QTxZKio2qF7G32CvptPzkd7D8IPzcqIUymSeErAXy9zTp1Ep2Vc9ttecV4DqNuV0VSGewUek-JvvBfI4gwaRJxOdZCvpoyDVRGfE5~xNYcGvmZr1WsAnHTOMRNmYDxGklQ52fw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

- ↑ "Details of Evolutionary Transition from Fish to Land Animals Revealed" (in English). https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=112416.

- ↑ Clack, Jennifer A. (November 21, 2005). "Getting a Leg Up on Land". Scientific American 293 (6): 100–107. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100. PMID 16323697. Bibcode: 2005SciAm.293f.100C. http://sciam.com/print_version.cfm?articleID=000DC8B8-EA15-137C-AA1583414B7F0000.

- ↑ Martin, R. Aidan. "Evolution of a Super Predator". North Vancouver, BC, Canada: ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/evolution/evol_s_predator.htm. "The ancestry of sharks dates back more than 200 million years before the earliest known dinosaur."

- ↑ "Devonian Fossil Forest Unearthed in China | Paleontology | Sci-News.com" (in en-US). http://www.sci-news.com/paleontology/xinhang-forest-07484.html.

- ↑ "Amphibia". https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=36319&is_real_user=1.

- ↑ Benton, M.J.; Donoghue, P.C.J. (2006). "Palaeontological evidence to date the tree of life". Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (1): 26–53. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl150. PMID 17047029.

- ↑ "Origin and Early Evolution of Amniotes | Frontiers Research Topic". https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14947/origin-and-early-evolution-of-amniotes#:~:text=Amniotes%20first%20appeared%20in%20the%20fossil%20record%20about%20318%20million,attention%20over%20the%20past%20decades..

- ↑ "Amniota". http://www.palaeos.org/Amniota.

- ↑ Kemp, T. S. (February 16, 2006). "The origin and early radiation of the therapsid mammal-like reptiles: a palaeobiological hypothesis" (in en). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 19 (4): 1231–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01076.x. ISSN 1010-061X. PMID 16780524.

- ↑ Rybicki, Ed (April 2008). "Origins of Viruses". Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa: University of Cape Town. http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/tutorial/virorig.html. "Viruses of nearly all the major classes of organisms - animals, plants, fungi and bacteria / archaea - probably evolved with their hosts in the seas, given that most of the evolution of life on this planet has occurred there. This means that viruses also probably emerged from the waters with their different hosts, during the successive waves of colonisation of the terrestrial environment."

- ↑ US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What are the vampire squid and the vampire fish?" (in EN-US). https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/vampire-squid-fish.html.

- ↑ Dell'Amore, Christine (April 24, 2014). "Meet Kryptodrakon: Oldest Known Pterodactyl Found in China". National Geographic News (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society). http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/04/140424-pterodactyl-pterosaur-china-oldest-science-animals/.

- ↑ Greshko, Michael (2020-02-11). "Oldest evidence of modern bees found in Argentina". https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/oldest-ever-fossil-bee-nests-discovered-in-patagonia. "The model shows that modern bees started diversifying at a breakneck pace about 114 million years ago, right around the time that eudicots—the plant group that comprises 75 percent of flowering plants—started branching out. The results, which confirm some earlier genetic studies, strengthen the case that flowering plants and pollinating bees have coevolved from the very beginning."

- ↑ Moreau, Corrie S.; Bell, Charles D.; Vila, Roger; Archibald, S. Bruce; Pierce, Naomi E. (2006-04-07). "Phylogeny of the Ants: Diversification in the Age of Angiosperms" (in en). Science 312 (5770): 101–104. doi:10.1126/science.1124891. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16601190. Bibcode: 2006Sci...312..101M. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1124891.

- ↑ "Case for 'river monster' Spinosaurus strengthened by new fossil teeth" (in en). 2020-09-23. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/case-for-river-monster-spinosaurus-strengthened-by-new-fossil-teeth.

- ↑ "Mindat.org". https://www.mindat.org/taxon-704.html.

- ↑ Grossnickle, David M.; Newham, Elis (2016-06-15). "Therian mammals experience an ecomorphological radiation during the Late Cretaceous and selective extinction at the K–Pg boundary". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283 (1832): 20160256. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.0256.

- ↑ "Mammals began their takeover long before the death of the dinosaurs" (in en). https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/06/160607220628.htm.

- ↑ Finds, Study (2021-12-02). "T-rex fossil reveals dinosaur from 68 million years ago likely had a terrible toothache!" (in en-US). https://studyfinds.org/t-rex-fossil-toothache/.

- ↑ "About > The Origins of Oaks". http://www.oaksofchevithornebarton.com/about-history-of-garden.cfm?.

- ↑ "International Stratigraphic Chart (v 2014/10)" (PDF). Beijing, China: International Commission on Stratigraphy. http://www.stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2014-10.jpg.

Bibliography

- Barton, Nicholas H.; Briggs, Derek E.G.; Eisen, Jonathan A.; Goldstein, David B.; Patel, Nipam H. (2007). Evolution. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-684-9. OCLC 86090399.

- Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol; Michod, Richard E. (2012). "DNA Repair as the Primary Adaptive Function of Sex in Bacteria and Eukaryotes". in Kimura, Sakura; Shimizu, Sora. DNA Repair: New Research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62100-808-8. OCLC 828424701. https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=31918.

- Bjornerud, Marcia (2005). Reading the Rocks: The Autobiography of the Earth. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-42498. OCLC 56672295. https://archive.org/details/readingrocksauto00bjor.

- Kirschvink, Joseph L. (1992). "Late Proterozoic Low-Latitude Global Glaciation: the Snowball Earth". in Schopf, J. William; Klein, Cornelis. The Proterozoic Biosphere: A Multidisciplinary Study. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36615-1. OCLC 23583672. http://web.gps.caltech.edu/~jkirschvink/pdfs/firstsnowball.pdf.

- McKinney, Michael L. (1997). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". in Kunin, William E.; Gaston, Kevin J.. The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences (1st ed.). London; New York: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-63380-5. OCLC 36442106.

- Miller, G. Tyler; Spoolman, Scott E. (2012). Environmental Science (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-1-111-98893-7. OCLC 741539226.

- Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, Stephen C. (1999). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07606-6. OCLC 47011675. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780300084696.

Further reading

- Dawkins, Richard (2004). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3. OCLC 56617123.

External links

- "Understanding Evolution: your one-stop resource for information on evolution". University of California, Berkeley. http://evolution.berkeley.edu/.

- "Life on Earth". University of Arizona. January 1, 1997. http://tolweb.org/Life_on_Earth/1. Explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively

- Brandt, Niel. "Evolutionary and Geological Timelines". Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc.. http://www.talkorigins.org/origins/geo_timeline.html.

- "Palaeos: Life Through Deep Time". http://www.palaeos.com.

- Kyrk, John. "Evolution" (SWF). http://www.johnkyrk.com/evolution.html. Interactive timeline from Big Bang to present

- "Plant Evolution". University of Waikato. http://sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/plantEvolution.shtml. Sequence of Plant Evolution

- "The History of Animal Evolution". University of Waikato. http://sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/AnimalEvolution.shtml. Sequence of Animal Evolution

- Yeo, Dannel; Drage, Thomas (2006). "History of Life on Earth". http://draget.net/hoe/index.php.

- Exploring Time. The Science Channel. 2007. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- Roberts, Ben. "Plant evolution timeline". University of Cambridge. http://www.plantsci.cam.ac.uk/timeline/.

- Art of the Nature Timelines on Wikipedia

|