Engineering:Falcon (rocket family)

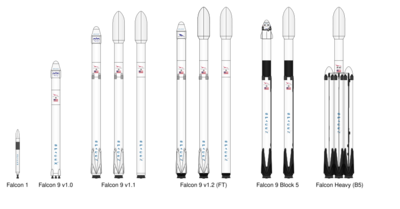

The Falcon rocket family is an American family of multi-use rocket launch vehicles developed and operated by Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX).

The vehicles in this family include the flight-tested Falcon 1, Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy. The Falcon 1 made its first successful flight on 28 September 2008, after several failures on the initial attempts. The larger Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV)-class Falcon 9 flew successfully into orbit on its maiden launch on 4 June 2010. The Falcon 9 was designed for reuse; over a dozen first stages have landed vertically, and several have been launched again. SpaceX's three-core variant, Falcon Heavy, was successfully launched on February 6, 2018.

Naming

Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, has stated that the Falcon rockets are named after the Millennium Falcon from the Star Wars film series.[1]

Current launch vehicles

Falcon 9 "Full Thrust" v1.2

The Falcon 9 v1.2 (nicknamed "Full Thrust") is an upgraded version of the Falcon 9 V1.1. It was used the first time on 22 December 2015 for the ORBCOMM-2 launch at Cape Canaveral SLC-40 launch pad.

The first stage was upgraded with a larger liquid oxygen tank, loaded with subcooled propellants to allow a greater mass of fuel in the same tank volume. The second stage was also extended for greater fuel tank capacity. These upgrades brought a 33% increase to the previous rocket performance.[2]

Falcon Heavy

Falcon Heavy (FH) is a super heavy lift space launch vehicle designed and manufactured by SpaceX. The Falcon Heavy is a variant of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle comprising three Falcon 9 first stages: a reinforced center core, and two additional side boosters. All three boosters are designed to be recovered and reused. The side boosters assigned to Falcon Heavy's first flight were recovered from two prior Falcon 9 missions. SpaceX successfully launched the Falcon Heavy on February 6, 2018, delivering a payload comprising Musk's personal Tesla Roadster (playing Life On Mars?, by David Bowie) onto a trajectory reaching the orbit of Mars.[3]

Retired

Falcon 1

On 26 March 2006, the Falcon 1's maiden flight failed only seconds after leaving the pad due to a fuel line rupture.[4][5] After a year, the second flight was launched on 22 March 2007 and it also ended in failure, due to a spin stabilization problem that automatically caused sensors to turn off the Merlin 2nd-stage engine.[6] The third Falcon 1 flight used a new regenerative cooling system for the first-stage Merlin engine, and the engine development was responsible for the almost 17-month flight delay.[7] The new cooling system turned out to be the major reason the mission failed; because the first stage rammed into the second-stage engine bell at staging, due to excess thrust provided by residual propellant left over from the higher-propellant-capacity cooling system.[7] On 28 September 2008, the Falcon 1 succeeded in reaching orbit on its fourth attempt, becoming the first privately funded, liquid-fueled rocket to do so.[8] The Falcon 1 carried its first and only successful commercial payload into orbit on 13 July 2009, on its fifth launch.[9] No launch attempts of the Falcon 1 have been made since 2009, and SpaceX is no longer taking launch reservations for the Falcon 1 in order to concentrate company resources on its larger Falcon 9 launch vehicle and other development projects.

Falcon 1e

The Falcon 1e is an upgraded version of the Falcon 1 with a larger fairing and payload mass, and is 6.1 metres (20 ft) longer than the Falcon 1.[10] By December 2010, Falcon 1e replaced the services of Falcon 1 on the SpaceX product list.[11]

The 1e version has not yet been flown and is not currently scheduled to make a flight. Continued development and use of the Falcon 1/1e have been stagnant while the company focuses on the Falcon 9/Dragon program.[12]

Falcon 9 v1.0

The first version of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, Falcon 9 v1.0, was developed in 2005–2010, and was launched for the first time in 2010. Falcon 9 v1.0 made five flights in 2010–2013, when it was retired.

Falcon 9 v1.1

On 8 September 2005, SpaceX announced the development of the Falcon 9 rocket, which has nine Merlin engines in its first stage.[13] The design is an EELV-class vehicle, intended to compete with the Delta IV and the Atlas V, along with launchers of other nations as well. Both stages were designed for reuse. A similarly designed Falcon 5 rocket was also envisioned to fit between[citation needed] the Falcon 1 and Falcon 9, but development was dropped to concentrate on the Falcon 9.[13]

The first version of the Falcon 9, Falcon 9 v1.0, was developed in 2005–2010, and flew five orbital missions in 2010–2013. The second version of the launch system—Falcon 9 v1.1— has been retired meanwhile.

Falcon 9 v1.1 was developed in 2010-2013, and made its maiden flight in September 2013. The Falcon 9 v1.1 is a 60 percent heavier rocket with 60 percent more thrust than the v1.0 version of the Falcon 9.[14] It includes realigned first-stage engines[15] and 60 percent longer fuel tanks, making it more susceptible to bending during flight.[14] The engines themselves have been upgraded to the more powerful Merlin 1D. These improvements will increase the payload capability from 9,000 kilograms (20,000 lb) to 13,150 kilograms (28,990 lb).[16]

The stage separation system has been redesigned and reduces the number of attachment points from twelve to three,[14] and the vehicle has upgraded avionics and software as well.[14]

The new first stage will also be used as side boosters on the Falcon Heavy launch vehicle.[17]

The company purchased the McGregor, Texas, testing facilities of defunct Beal Aerospace, where it refitted the largest test stand at the facilities for Falcon 9 testing. On 22 November 2008, the stand tested the nine Merlin 1C engines of the Falcon 9, which deliver 350 metric-tons-force (3.4-meganewtons) of thrust, well under the stand's capacity of 1,500 metric-tons-force (15 meganewtons).[18]

The first Falcon 9 vehicle was integrated at Cape Canaveral on 30 December 2008. NASA was planning for a flight to take place in January 2010;[19] however the maiden flight was postponed several times and took place on 4 June 2010.[20] At 2:50pm EST the Falcon 9 rocket successfully reached orbit.

The second flight for the Falcon 9 vehicle was the COTS Demo Flight 1, the first launch under the NASA Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) contract designed to provide "seed money" for development of new boosters.[21] The original NASA contract called for the COTS Demo Flight 1 to occur the second quarter of 2008;[22] this flight was delayed several times, occurring at 15:43 GMT on 8 December 2010.[23] The rocket successfully deployed an operational Dragon spacecraft at 15:53 GMT.[23] Dragon orbited the Earth twice, and then made a controlled reentry burn that put it on target for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Mexico.[24] With Dragon's safe recovery, SpaceX became the first private company to launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft; prior to this mission only government agencies had been able to recover orbital spacecraft.[24] The first flight of the Falcon 9 v1.1 was September 29, 2013 from Vandenberg Air Force Base carrying several payloads including Canada's CASSIOPE technology demonstration satellite.[25] The Falcon 9 v1.1 features stretched first and second stages, and a new octagonal arrangement of the 9 Merlin-1D engines on the first stage (replacing the square pattern of engines in v1.0). SpaceX notes that the Falcon 9 v1.1 is cheaper to manufacture, and longer than v1.0. It also has a larger payload capacity: 13,150 kilograms to low Earth orbit or 4,850 kg to geosynchronous transfer orbit.[25]

Grasshopper

Grasshopper was an experimental technology-demonstrator, suborbital reusable launch vehicle (RLV), a vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) rocket.[26] The first VTVL flight test vehicle—Grasshopper, built on a Falcon 9 v1.0 first-stage tank—made a total of eight test flights between September 2012 and October 2013.[27] All eight flights were from the McGregor, Texas, test facility.

Grasshopper began flight testing in September 2012 with a brief, three-second hop. It was followed by a second hop in November 2012, which consisted of an 8-second flight that took the testbed approximately 5.4 m (18 ft) off the ground. A third flight occurred in December 2012 of 29 seconds duration, with extended hover under rocket engine power, in which it ascended to an altitude of 40 m (130 ft) before descending under rocket power to come to a successful vertical landing.[28] Grasshopper made its eighth and final test flight on October 7, 2013, flying to an altitude of 744 m (2,441 ft; 0.462 mi) before making its eighth successful vertical landing.[29] The Grasshopper test vehicle is now retired.[27]

Cancelled

Falcon 5

An early five-engine booster stage launch vehicle, the Falcon 5, was in design but its development was stopped in favor of the larger nine-engine Falcon 9.[30] Like the Falcon 9, it was also slated to be human-rated and reusable.[30]

Falcon 9 Air

In December 2011 Stratolaunch Systems announced that it would contract with SpaceX to develop an air-launched, multiple-stage launch vehicle, as a derivative of Falcon 9 technology, called the Falcon 9 Air,[31] as part of the Stratolaunch project.[32] On 27 November 2012 Stratolaunch announced that they would partner with Orbital Sciences Corporation instead of SpaceX, effectively ending development of the Falcon 9 Air.[33]

Proposed

BFR

The Big Falcon Rocket (commonly shortened to BFR), announced in September 2017, is SpaceX's proposed super-heavy-lift launch vehicle, spacecraft and space-ground infrastructure system of spaceflight technology, including reusable launch vehicles and spacecraft. This vehicle would ultimately replace the Falcon 9 and Heavy lines of SpaceX launch vehicles. BFR is proposed to be used for Earth ground-to-ground flight, cis-Lunar flight, and with the Interplanetary Transport System variant, interplanetary flight to Mars or other targets and would be a central component in the SpaceX Mars transportation infrastructure.[34]

Competitive position

SpaceX Falcon rockets are being offered to the launch industry at highly competitive prices, allowing SpaceX to build up a large manifest of over 50 launches by late 2013, with two-thirds of them for commercial customers exclusive of US government flights.[35][36]

In the US launch industry, SpaceX prices its product offerings well below its competition. Nevertheless, "somewhat incongruously, its primary US competitor, United Launch Alliance (ULA), still maintain[ed in early 2013] that it requires a large annual subsidy, which neither SpaceX nor Orbital Sciences receives, in order to remain financially viable, with the reason cited as a lack of market opportunity, a stance which seems to be in conflict with the market itself."[37]

SpaceX launched its first satellite to geostationary orbit in December 2013 (SES-8) and followed that a month later with its second, Thaicom 6, beginning to offer competition to the European and Russian launch providers that had been the major players in the commercial communications satellite market in recent years.[36]

SpaceX prices undercut its major competitors—the Ariane 5 and Proton—in this market,[38] and SpaceX has at least 10 further geostationary orbit flights on its books.[36]

Moreover, SpaceX prices for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy are much lower than the projected prices for the new Ariane 5 ME upgrade and its Ariane 6 successor, projected to be available in 2018 and 2021, respectively.[39]

As a result of additional mission requirements for government launches, SpaceX prices US government missions somewhat higher than similar commercial missions, but has noted that even with those added services, Falcon 9 missions contracted to the government are still priced well below US$100 million (even with approximately US$9 million in special security charges for some missions) which is a very competitive price compared to ULA prices for government payloads of the same size.[40]

ULA prices to the US government are nearly $400 million for current launches of Falcon 9- and Falcon Heavy-class payloads.[41]

Comparison

| Falcon 1 | Falcon 1e | Falcon 9 v1.0 | Falcon 9 v1.1 | Falcon 9 Full Thrust | Falcon Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | − | − | − | − | − | 2 boosters with 9 × Merlin 1D (with minor upgrades)[42][A] |

| Stage 1 | 1 × Merlin 1C[B] | 1 × Merlin 1C | 9 × Merlin 1C | 9 × Merlin 1D | 9 × Merlin 1D (with minor upgrades)[42] | 9 × Merlin 1D (with minor upgrades)[43] |

| Stage 2 | 1 × Kestrel | 1 × Kestrel | 1 × Merlin Vacuum | 1 × Merlin Vacuum | 1 × Merlin 1D Vacuum (with minor upgrades)[42][43] | 1 × Merlin 1D Vacuum (with minor upgrades)[42][43] |

| Max. height (m) | 21.3 | 26.83 | 54.9[44] | 68.4[45] | 70[43][46] | 70[43][46] |

| Diameter (m) | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.6[44] | 3.7[45][47] | 3.7[45][47] | 3.7 × 11.6[48] |

| Initial thrust (kN) | 318 | 454 | 4,900[44] | 5,885[45] | 22,819[48] | |

| Takeoff mass (tonnes) | 27.2 | 38.56 | 333[44] | 506[45] | 549[46] | 1,421[48] |

| Inner fairing diameter (m) | 1.5 | 1.71 | 3.7 or 5.2[44] | 5.2[45][47] | 5.2 | 5.2[48] |

| LEO payload (kg) | 570 | 1,010 | 10,450[44] | 13,150[45] | 22,800 (expendable, from Cape Canaveral)[51] | 63,800 (expendable)[48] |

| GTO payload (kg) | − | − | 4,540[44] | 4,850[45][47] | 26,700 (expendable)[48] | |

| Price history (mil. United States dollar ) |

2006: 6.7 [54] 2007: 6.9 [55] 2008: 7.9 [54] |

2007: 8.5 [54] 2008: 9.1 [54] 2010: 10.9 [54] |

2005: 27 (3.6 m fairing to LEO) 35 (5.2 m fairing to LEO)[56] 2011: 54 to 59.5[44] |

2013: 54[57] – 56.5[16] | 2014: 61.2 [46] | 2011: 80 to 124 [58] 2012: 83 to 128[59] 2013: 77.1 (≤6,400 kg to GTO)[16] 135 (>6,400 kg to GTO)[16] |

| Current price (mil. United States dollar ) | − | − | − | — | 62 (≤5,500 kg to GTO)[60] | 90 (≤8,000 kg to GTO)[60] |

| Success ratio (successful/total) | 2/5 | − | 5/5[61] | 14/15 (CRS-7 lost in flight) | 33/34 (Amos-6 exploded on launch pad) | 1/1 |

A Optional propellant crossfeed for increased launch mass capability

B Post 2008. Merlin 1A was used from 2006 till 2007.[62]

See also

- BFR (rocket)

- SpaceX Dragon

- SpaceX rocket engines

- Merlin (rocket engine family)

- Raptor (rocket engine family), methane-fueled

- List of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches

References

- ↑ "Joseph Gordon-Levitt at SpaceX". Youtube. p. timeindex 2:25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwMIAKabRng.

- ↑ SpaceX ORBCOMM-2 webcast

- ↑ "SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch successful". CBS News. February 6, 2018. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/watch-live-falcon-heavy-launch-spacex-online-stream-live-updates/. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ↑ Malik, Tariq (2006-03-26). "Article: Fuel Leak and Fire Led to Falcon 1 Rocket Failure, SpaceX Says". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63cH1CmQf?url=http://www.space.com/2200-fuel-leak-fire-led-falcon-1-rocket-failure-spacex.html. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ Malik, Tariq (2006-03-26). "SpaceX's Inaugural Falcon 1 Rocket Lost Just After Launch". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63cGRYEXl?url=http://www.space.com/2196-spacex-inaugural-falcon-1-rocket-lost-launch.html. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUToday 20070322 - ↑ 7.0 7.1 O'Neill, Ian (2008-08-16). "Video of SpaceX Falcon 1 Flight 3 Launch Shows Stage Separation Anomaly". The Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63cEc3Uzp?url=http://www.universetoday.com/16900/video-of-spacex-falcon-1-flight-3-shows-stage-separation-anomaly/. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "SpaceX Successfully Launches Falcon 1 To Orbit" (Press release). SpaceX. 28 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Rowe, Aaron (2009-07-14). "SpaceX Launch Successfully Delivers Satellite Into Orbit". Wired Science. https://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2009/07/spacexlaunch/. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ↑ "Falcon 1 Launch Vehicle Payload User's Guide". Space Exploration Technologies Corporation. May 2008. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120222034638/http://www.spacex.com/Falcon1UsersGuide.pdf. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ↑ "Falcon 1 Overview". SpaceX. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63bt3gje9?url=http://www.spacex.com/falcon1.php. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ O'Neill, Ian (2011-09-30). "The Falcon is Dead, Long Live the Falcon?". Discovery News. http://news.discovery.com/space/spacex-falcon-1-production-freeze-110930.html. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "SpaceX announces the Falcon 9 fully reusable heavy lift launch vehicle" (Press release). SpaceX.com. 2005-09-08. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Klotz, Irene (2013-09-06). "Musk Says SpaceX Being "Extremely Paranoid" as It Readies for Falcon 9's California Debut". Space News. http://www.spacenews.com/article/launch-report/37094musk-says-spacex-being-%E2%80%9Cextremely-paranoid%E2%80%9D-as-it-readies-for-falcon-9%E2%80%99s. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ↑ "Falcon 9's commercial promise to be tested in 2013". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/news/n1211/17f9customers/#.UKfUruQ0V8E. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "SpaceX Capabilities and Services". webpage. SpaceX. 2013. http://www.spacex.com/about/capabilities. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ↑ "Space Launch report, SpaceX Falcon Data Sheet". http://www.spacelaunchreport.com/falcon9.html. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- ↑ "Falcon 9 Progress Update: 22 November 2008". SpaceX. 2008-11-22. http://www.spacex.com/updates.php#Update082808.

- ↑ "Launches — Mission Set Database". NASA GSFC. Archived from the original on 2009-03-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20090320221234/http://msdb.gsfc.nasa.gov/launches.php. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ↑ "NASA Mission Set Database". NASA. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. https://web.archive.org/web/20111016081034/http://msdb.gsfc.nasa.gov/MissionData.php?mission=Falcon-9%20ELV%20First%20Flight%20Demonstration. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ↑ "NASA Awards Launch Services Contract to SpaceX" (Press release). NASA. 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ↑ "COTS contract". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/pdf/189228main_setc_nnj06ta26a.pdf. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Mission Status Center". SpaceFlightNow. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/002/status.html. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Bates, Daniel (2010-12-09). "Mission accomplished! SpaceX Dragon becomes the first privately funded spaceship launched into orbit and guided back to earth". The Daily Mail (London). Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63c6Ifoce?url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1336868/SpaceX-Dragon-privately-funded-spaceship-launched-orbit.html. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 William Graham (2013-09-29). "SpaceX successfully launches debut Falcon 9 v1.1". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2013/09/spacex-debut-falcon-9-v1-1-cassiope-launch/. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- ↑ Klotz, Irene (2011-09-27). "A rocket that lifts off—and lands—on launch pad". MSNBC. http://satellite.tmcnet.com/topics/satellite/articles/222324-spacex-plans-test-reusable-suborbital-vtvl-rocket-texas.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Klotz, Irene (2013-10-17). "SpaceX Retires Grasshopper, New Test Rig To Fly in December". Space News. http://www.spacenews.com/article/launch-report/37740spacex-retires-grasshopper-new-test-rig-to-fly-in-december. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (2012-12-24). "SpaceX launches its Grasshopper rocket on 12-story-high hop in Texas". MSNBC Cosmic Log. http://cosmiclog.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/12/23/16114180-spacex-launches-its-grasshopper-rocket-on-12-story-high-hop-in-texas. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ "Grasshopper flies to its highest height to date". Social media information release. SpaceX. 12 October 2013. https://www.facebook.com/SpaceX/posts/10153372146765131. Retrieved 14 October 2013. "WATCH: Grasshopper flies to its highest height to date - 744 m (2441 ft) into the Texas sky. http://youtu.be/9ZDkItO-0a4 This was the last scheduled test for the Grasshopper rig; next up will be low altitude tests of the Falcon 9 Reusable (F9R) development vehicle in Texas followed by high altitude testing in New Mexico."

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Wade, Mark (2011). "Falcon 5". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63cIE9NJo?url=http://www.astronautix.com/lvs/falcon5.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "The Stratolaunch Team". Stratoluanch Systems. 2011. http://stratolaunch.com/team.html. Retrieved 2011-12-20. "... integrate the SpaceX Falcon 9 Air with the Scaled Composites mothership."

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2011-12-13). "Stratolaunch introduce Rutan designed air-launched system for Falcon rockets". NASAspaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-14. https://www.webcitation.org/63vjHScLL?url=http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2011/12/stratolaunch-rutan-designed-air-launched-system-falcon-rockets/. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Zach (2012-11-27). "Stratolaunch and SpaceX part ways". Flight Global. http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/stratolaunch-and-spacex-part-ways-379516/. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (29 September 2017). "Musk unveils revised version of giant interplanetary launch system". SpaceNews. http://spacenews.com/musk-unveils-revised-version-of-giant-interplanetary-launch-system/. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ↑ Dean, James (2013-12-04). "SpaceX makes its point with Falcon 9 launch". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2013/12/04/spacex-launch-successful/3866655/. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Stephen Clark (3 December 2013). "Falcon 9 rocket launches first commercial telecom payload". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/007/131203launch/. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Money, Stewart (2013-01-30). "SpaceX Wins New Commercial Launch Order". Innerspace.net. http://innerspace.net/2013/01/30/spacex-wins-new-commercial-launch-order/. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (24 November 2013). "Sizing up America's place in the global launch industry". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20131203224447/http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/007/131124commercial/. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ Messier, Doug (2014-01-18). "ESA Faces Large Cost for Ariane 5 Upgrade, New Ariane 6 Rocket". Parabolic Arc.

- ↑ Gwynne Shotwell (2014-03-21). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 06:00–07:30. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

It is more expensive to do these missions; the Air Force asks for more stuff. The missions that we do for NASA under the NLS contract are also more expensive, because NASA asks to do more analysis, they have us provide more data to them, they have folks who reside here at SpaceX, and we need to provide engineering resources to them to respond to their questions. ... the NASA extra stuff is about $10 million; Air Force stuff is about an extra $20 million, and then if there is high security requirements that can add another 8–10 million. But all in, Falcon 9 prices are still well below $100 million, even with all the stuff, which is really quite a competitive price compared to what ULA is offering.

- ↑ William Harwood (5 March 2014). "SpaceX, ULA spar over military contracting". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/news/n1403/05spacexula/. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Foust, Jeff (31 August 2015). "SpaceX To Debut Upgraded Falcon 9 on Return to Flight Mission". http://spacenews.com/spacex-to-debut-upgraded-falcon-9-on-return-to-flight-mission/. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 "Falcon 9 Launch Vehicle Payload User's Guide, Rev 2". 21 October 2015. http://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/falcon_9_users_guide_rev_2.0.pdf. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 44.6 44.7 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsxf9_20111201archive - ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 45.7 "Falcon 9". SpaceX. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-07-15. https://web.archive.org/web/20130715094112/http://www.spacex.com/falcon9. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140901165450/http://www.spacex.com/about/capabilities. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 "Space Launch Report : Vehicle Configurations". SLR SpaceX Falcon Data Sheet (tertiary source). Space Launch Report. 2012-12-17. http://www.spacelaunchreport.com/falcon9.html. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 "Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 2013. http://www.spacex.com/falcon-heavy. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ @elonmusk (1 May 2016). "F9 thrust at liftoff will be raised to 1.71M lbf later this year. It is capable of 1.9M lbf in flight.". https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/726650591359819776.

- ↑ "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130715094112/http://www.spacex.com/falcon9. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. http://www.spacex.com/about/capabilities. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (February 8, 2016). "SpaceX prepares for SES-9 mission and Dragon's return". NASA Spaceflight. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2016/02/spacex-prepares-ses-9-mission-dragons-return/. Retrieved February 9, 2016. "The aforementioned Second Stage will be tasked with a busy role during this mission, lofting the 5,300kg SES-9 spacecraft to its Geostationary Transfer Orbit."

- ↑ Barbara Opall-Rome (12 October 2015). "IAI Develops Small, Electric-Powered COMSAT". DefenseNews. http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/2015/10/12/iai-develops-small-electric-powered-comsat/73808432/. Retrieved 12 October 2015. "At 5.3 tons, Amos-6 is the largest communications satellite ever built by IAI. Scheduled for launch in early 2016 from Cape Canaveral aboard a Space-X Falcon 9 launcher, Amos-6 will replace Amos-2, which is nearing the end of its 16-year life."

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 "SpaceX Falcon Data Sheet". Space Launch Report. 2007-07-05. http://www.spacelaunchreport.com/falcon.html#config.

- ↑ Hoffman, Carl (2007-05-22). "Elon Musk Is Betting His Fortune on a Mission Beyond Earth's Orbit". Wired Magazine. https://www.wired.com/science/space/magazine/15-06/ff_space_musk?currentPage=all. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ↑ Leonard, David. "SpaceX to Tackle Fully Reusable Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle". http://www.space.com/1533-spacex-tackle-fully-reusable-heavy-lift-launch-vehicle.html. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "Falcon Heavy Overview". SpaceX. 2013. http://www.spacex.com/falcon_heavy.php. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ↑ "Falcon Heavy Overview". SpaceX. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. https://www.webcitation.org/63bpIzENm?url=http://www.spacex.com/falcon_heavy.php. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation — Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 2011-12-03. http://www.spacex.com/falcon_heavy.php. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Capabilities and Services". SpaceX. 2014. http://www.spacex.com/about/capabilities. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ "Dragon spacecraft heads toward International Space Station". SpaceX. 2013-03-01. https://spacex.com/press.php?page=20130301. Retrieved 2013-03-03.

- ↑ "Updates Archive". SpaceX. 2007-12-10. http://www.spacex.com/updates_archive.php?page=121007#Update121007. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Falcon rockets. |