Medicine:Abdominal aortic aneurysm

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | |

|---|---|

| |

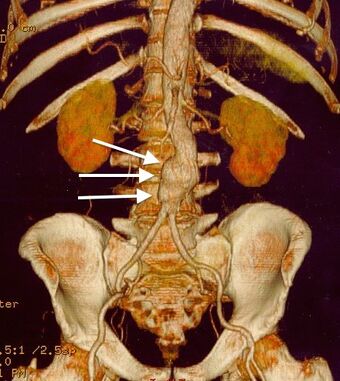

| CT reconstruction image of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (white arrows) | |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery |

| Symptoms | None, abdominal, back, or leg pain[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Over 50 year old males[1] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, hypertension, other cardiovascular disease, family history, Marfan syndrome[1][3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging (abdominal aorta diameter > 3 cm)[1] |

| Prevention | Not smoking, treating risk factors[1] |

| Treatment | Surgery (open surgery or endovascular aneurysm repair)[1] |

| Frequency | ~5% (males over 65 years)[1] |

| Deaths | 168,200 aortic aneurysms (2015)[5] |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a localized enlargement of the abdominal aorta such that the diameter is greater than 3 cm or more than 50% larger than normal.[1] An AAA usually causes no symptoms, except during rupture.[1] Occasionally, abdominal, back, or leg pain may occur.[2] Large aneurysms can sometimes be felt by pushing on the abdomen.[2] Rupture may result in pain in the abdomen or back, low blood pressure, or loss of consciousness, and often results in death.[1][6]

AAAs occur most commonly in men, those over 50 and those with a family history of the disease.[1] Additional risk factors include smoking, high blood pressure, and other heart or blood vessel diseases.[3] Genetic conditions with an increased risk include Marfan syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.[4] AAAs are the most common form of aortic aneurysm.[4] About 85% occur below the kidneys, with the rest either at the level of or above the kidneys.[1] In the United States , screening with abdominal ultrasound is recommended for males between 65 and 75 years of age with a history of smoking.[7] In the United Kingdom and Sweden, screening all men over 65 is recommended.[1][8] Once an aneurysm is found, further ultrasounds are typically done on a regular basis.[2]

Abstinence from cigarette smoking is the single best way to prevent the disease.[1] Other methods of prevention include treating high blood pressure, treating high blood cholesterol, and avoiding being overweight.[1] Surgery is usually recommended when the diameter of an AAA grows to >5.5 cm in males and >5.0 cm in females.[1] Other reasons for repair include the presence of symptoms and a rapid increase in size, defined as more than one centimeter per year.[2] Repair may be either by open surgery or endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR).[1] As compared to open surgery, EVAR has a lower risk of death in the short term and a shorter hospital stay, but may not always be an option.[1][9][10] There does not appear to be a difference in longer-term outcomes between the two.[11] Repeat procedures are more common with EVAR.[12]

AAAs affect 2-8% of males over the age of 65.[1] They are five times more common in men.[13] In those with an aneurysm less than 5.5 cm, the risk of rupture in the next year is below 1%.[1] Among those with an aneurysm between 5.5 and 7 cm, the risk is about 10%, while for those with an aneurysm greater than 7 cm the risk is about 33%.[1] Mortality if ruptured is 85% to 90%.[1] During 2013, aortic aneurysms resulted in 168,200 deaths, up from 100,000 in 1990.[5][14] In the United States AAAs resulted in between 10,000 and 18,000 deaths in 2009.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The vast majority of aneurysms are asymptomatic. However, as the abdominal aorta expands and/or ruptures, the aneurysm may become painful and lead to pulsating sensations in the abdomen or pain in the chest, lower back, legs, or scrotum.[15]

Complications

The complications include rupture, peripheral embolization, acute aortic occlusion, and aortocaval (between the aorta and inferior vena cava) or aortoduodenal (between the aorta and the duodenum) fistulae. On physical examination, a palpable and pulsatile abdominal mass can be noted. Bruits can be present in case of renal or visceral arterial stenosis.[16]

The signs and symptoms of a ruptured AAA may include severe pain in the lower back, flank, abdomen or groin. A mass that pulses with the heart beat may also be felt.[6] The bleeding can lead to a hypovolemic shock with low blood pressure and a fast heart rate, which may cause fainting.[6] The mortality of AAA rupture is as high as 90 percent. 65 to 75 percent of patients die before they arrive at the hospital and up to 90 percent die before they reach the operating room.[17] The bleeding can be retroperitoneal or into the abdominal cavity. Rupture can also create a connection between the aorta and intestine or inferior vena cava.[18] Flank ecchymosis (appearance of a bruise) is a sign of retroperitoneal bleeding and is also called Grey Turner's sign.[16][19]

Causes

The exact causes of the degenerative process remain unclear. There are, however, some hypotheses and well-defined risk factors.[20]

- Tobacco smoking: More than 90% of people who develop an AAA have smoked at some point in their lives.[21]

- Alcohol and hypertension: The inflammation caused by prolonged use of alcohol and hypertensive effects from abdominal edema which leads to hemorrhoids, esophageal varices, and other conditions, is also considered a long-term cause of AAA.[citation needed]

- Genetic influences: The influence of genetic factors is high. AAA is four to six times more common in male siblings of known patients, with a risk of 20–30%.[22] The high familial prevalence rate is most notable in male individuals.[23] There are many hypotheses about the exact genetic disorder that could cause higher incidence of AAA among male members of the affected families. Some presumed that the influence of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency could be crucial, while other experimental works favored the hypothesis of X-linked mutation, which would explain the lower incidence in heterozygous females. Other hypotheses of genetic causes have also been formulated.[16] Connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, have also been strongly associated with AAA.[18] Both relapsing polychondritis and pseudoxanthoma elasticum may cause abdominal aortic aneurysm.[24]

- Atherosclerosis: The AAA was long considered to be caused by atherosclerosis, because the walls of the AAA frequently carry an atherosclerotic burden. However, this hypothesis cannot explain the initial defect and the development of occlusion, which is observed in the process.[16] Another hypothesis is that plaque buildup can cause a feed-forward dysfunction in the signaling among neurons that regulate pressure in the aorta. This feed-forward process leads to an over-pressuring condition that ruptures in the aorta.[25]

- Other causes of the development of AAA include: infection, trauma, arteritis, and cystic medial necrosis.[18]

Pathophysiology

File:Aortic Aneurism 76F 3D SR Nevit Dilmen.stl The most striking histopathological changes of the aneurysmatic aorta are seen in the tunica media and intima layers. These changes include the accumulation of lipids in foam cells, extracellular free cholesterol crystals, calcifications, thrombosis, and ulcerations and ruptures of the layers. Adventitial inflammatory infiltrate is present.[18] However, the degradation of the tunica media by means of a proteolytic process seems to be the basic pathophysiologic mechanism of AAA development. Some researchers report increased expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases in individuals with AAA. This leads to elimination of elastin from the media, rendering the aortic wall more susceptible to the influence of blood pressure.[16] Other reports have suggested the serine protease granzyme B may contribute to aortic aneurysm rupture through the cleavage of decorin, leading to disrupted collagen organization and reduced tensile strength of the adventitia.[26][27] There is also a reduced amount of vasa vasorum in the abdominal aorta (compared to the thoracic aorta); consequently, the tunica media must rely mostly on diffusion for nutrition, which makes it more susceptible to damage.[28]

Hemodynamics affect the development of AAA, which has a predilection for the infrarenal aorta. The histological structure and mechanical characteristics of the infrarenal aorta differ from those of the thoracic aorta. The diameter decreases from the root to the aortic bifurcation, and the wall of the infrarenal aorta also contains a lesser proportion of elastin. The mechanical tension in the abdominal aortic wall is therefore higher than in the thoracic aortic wall. The elasticity and distensibility also decline with age, which can result in gradual dilatation of the segment. Higher intraluminal pressure in patients with arterial hypertension markedly contributes to the progression of the pathological process.[18] Suitable hemodynamic conditions may be linked to specific intraluminal thrombus (ILT) patterns along the aortic lumen, which in turn may affect AAA's development.[29]

Diagnosis

An abdominal aortic aneurysm is usually diagnosed by physical exam, abdominal ultrasound, or CT scan. Plain abdominal radiographs may show the outline of an aneurysm when its walls are calcified. However, the outline will be visible by X-ray in less than half of all aneurysms. Ultrasonography is used to screen for aneurysms and to determine their size if present. Additionally, free peritoneal fluid can be detected. It is noninvasive and sensitive, but the presence of bowel gas or obesity may limit its usefulness. CT scan has nearly 100% sensitivity for an aneurysm and is also useful in preoperative planning, detailing the anatomy and possibility for endovascular repair. In the case of suspected rupture, it can also reliably detect retroperitoneal fluid. Alternative less often used methods for visualization of an aneurysm include MRI and angiography.[citation needed]

An aneurysm ruptures if the mechanical stress (tension per area) exceeds the local wall strength; consequently, peak wall stress (PWS),[30] mean wall stress (MWS),[31] and peak wall rupture risk (PWRR)[32] have been found to be more reliable parameters than diameter to assess AAA rupture risk. Medical software allows computing these rupture risk indices from standard clinical CT data and provides a patient-specific AAA rupture risk diagnosis.[33][34][35] This type of biomechanical approach has been shown to accurately predict the location of AAA rupture.[34][35][36]

-

Aortic measurement on abdominal ultrasonography in the axial plane between the outer margins of the aortic wall[37]

-

Ultrasonography in the sagittal plane, showing axial plane measure (dashed red line), as well as maximal diameter (dotted yellow line), which is preferred

-

A ruptured AAA with an open arrow marking the aneurysm and the closed arrow marking the free blood in the abdomen

-

Sagittal CT image of an AAA

-

Biomechanical AAA rupture risk prediction

-

An axial contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrating an abdominal aortic aneurysm of 4.8 by 3.8 cm

-

The faint outline of the calcified wall of an AAA as seen on plain X-ray

-

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (3.4 cm)

-

An aortic aneurysm as seen on CT with a small area of remaining blood flow

-

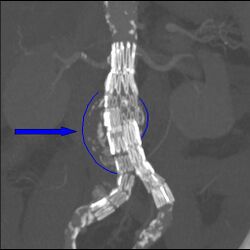

Ultrasound showing a previously repaired AAA that is leaking with flow around the graft[38]

-

Ultrasonography of an aneurysm with a mural thrombus

Classification

| Ectatic or mild dilatation |

>2.0 cm and <3.0 cm[39] |

| Moderate | 3.0 - 5.0 cm[39] |

| Large or severe | >5.0[39] or 5.5[40] cm |

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are commonly divided according to their size and symptomatology. An aneurysm is usually defined as an outer aortic diameter over 3 cm (normal diameter of the aorta is around 2 cm),[41] or more than 50% of normal diameter.[42] If the outer diameter exceeds 5.5 cm, the aneurysm is considered to be large.[40] Ruptured AAA should be suspected in any person older than 60 who experiences collapse, unexplained low blood pressure, or sudden-onset back or abdominal pain. Abdominal pain, shock, and a pulsatile mass is only present in a minority of cases.[citation needed] Although an unstable person with a known aneurysm may undergo surgery without further imaging, the diagnosis will usually be confirmed using CT or ultrasound scanning.[citation needed]

The suprarenal aorta normally measures about 0.5 cm larger than the infrarenal aorta.[43]

Differential diagnosis

Aortic aneurysm rupture may be mistaken for the pain of kidney stones, or muscle related back pain.[6]

Prevention

- Smoking cessation

- Treatment of hypertension

Screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a single screening abdominal ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm in males age 65 to 75 years who have a history of smoking.[44] Among this group who does not smoke, screening may be selective.[44] It is unclear if screening is useful in women who have smoked and the USPSTF recommend against screening in women who have never smoked.[7][45]

In the United Kingdom the NHS AAA Screening Programme invites men in England for screening during the year they turn 65. Men over 65 can contact the programme to arrange to be screened.[46]

In Sweden one time screening is recommended in all males over 65 years of age.[1][8] This has been found to decrease the risk of death from AAA by 42% with a number needed to screen of just over 200.[45] In those with a close relative diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm, Swedish guidelines recommend an ultrasound at around 60 years of age.[47]

Australia has no guideline on screening.[48]

Repeat ultrasounds should be carried out in those who have an aortic size greater than 3.0 cm.[49] In those whose aorta is between 3.0 and 3.9 cm this should be every three years, if between 4.0 and 4.4 cm every two years, and if between 4.5 and 5.4 cm every year.[49]

Management

The treatment options for asymptomatic AAA are conservative management, surveillance with a view to eventual repair, and immediate repair. Two modes of repair are available for an AAA: open aneurysm repair, and endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). An intervention is often recommended if the aneurysm grows more than 1 cm per year or it is bigger than 5.5 cm.[50] Repair is also indicated for symptomatic aneurysms. Ten years after open AAA repair, the overall survival rate was 59%.[51] Mycotic abdominal aorta aneurysm (MAAA) is a rare and life-threatening condition. Because of its rarity, there is a lack of adequately powered studies and consensus on its treatment and follow up. A management protocol on the management of mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm was recently published in the Annals of Vascular Surgery by Premnath et al.[52]

Conservative

Conservative management is indicated in people where repair carries a high risk of mortality and in patients where repair is unlikely to improve life expectancy. The mainstay of the conservative treatment is smoking cessation.[citation needed]

Surveillance is indicated in small asymptomatic aneurysms (less than 5.5 cm) where the risk of repair exceeds the risk of rupture.[50] As an AAA grows in diameter, the risk of rupture increases. Surveillance until an aneurysm has reached a diameter of 5.5 cm has not been shown to have a higher risk as compared to early intervention.[53][54]

Medication

No medical therapy has been found to be effective at decreasing the growth rate or rupture rate of asymptomatic AAAs.[1] Blood pressure and lipids should, however, be treated per usual.[41]

Surgery

The threshold for repair varies slightly from individual to individual, depending on the balance of risks and benefits when considering repair versus ongoing surveillance. The size of an individual's native aorta may influence this, along with the presence of comorbidities that increase operative risk or decrease life expectancy. Evidence, however, does not usually support repair if the size is less than 5.5 cm.[50]

Open repair

Open repair is indicated in young patients as an elective procedure, or in growing or large, symptomatic or ruptured aneurysms. The aorta must be clamped during the repair, denying blood to the abdominal organs and sections of the spinal cord; this can cause a range of complications. As it is essential to perform the critical part of the operation quickly, the incision is typically made large enough to facilitate the fastest repair. Recovery after open AAA surgery takes significant time. The minimums are a few days in intensive care, a week total in the hospital and a few months before full recovery.[citation needed]

Endovascular repair

Endovascular repair first became practical in the 1990s and although it is now an established alternative to open repair, its role is yet to be clearly defined. It is generally indicated in older, high-risk patients or patients unfit for open repair. However, endovascular repair is feasible for only a portion of AAAs, depending on the morphology of the aneurysm. The main advantages over open repair are that there is less peri-operative mortality, less time in intensive care, less time in hospital overall and earlier return to normal activity. Disadvantages of endovascular repair include a requirement for more frequent ongoing hospital reviews and a higher chance of further required procedures. According to the latest studies, the EVAR procedure does not offer any benefit for overall survival or health-related quality of life compared to open surgery, although aneurysm-related mortality is lower.[55][56][57][58] In patients unfit for open repair, EVAR plus conservative management was associated with no benefit, more complications, subsequent procedures and higher costs compared to conservative management alone.[59] Endovascular treatment for paraanastomotic aneurysms after aortobiiliac reconstruction is also a possibility.[60] A 2017 Cochrane review found tentative evidence of no difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair of ruptured AAA in the first month.[61]

Rupture

In those with aortic rupture of the AAA, treatment is immediate surgical repair. There appear to be benefits to allowing permissive hypotension and limiting the use of intravenous fluids during transport to the operating room.[62]

Prognosis

| AAA Size (cm) | Growth rate (cm/yr)[63] | Annual rupture risk (%)[64] |

|---|---|---|

| 3.0–3.9 | 0.39 | 0 |

| 4.0–4.9 | 0.36 | 0.5–5 |

| 5.0–5.9 | 0.43 | 3–15 |

| 6.0–6.9 | 0.64 | 10–20 |

| >=7.0 | - | 20–50 |

Although the current standard of determining rupture risk is based on maximum diameter, it is known that smaller AAAs that fall below this threshold (diameter<5.5 cm) may also rupture, and larger AAAs (diameter>5.5 cm) may remain stable.[65][66] In one report, it was shown that 10–24% of ruptured AAAs were less than 5 cm in diameter.[66] It has also been reported that of 473 non-repaired AAAs examined from autopsy reports, there were 118 cases of rupture, 13% of which were less than 5 cm in diameter. This study also showed that 60% of the AAAs greater than 5 cm (including 54% of those AAAs between 7.1 and 10 cm) never experienced rupture.[67] Vorp et al. later deduced from the findings of Darling et al. that if the maximum diameter criterion were followed for the 473 subjects, only 7% (34/473) of cases would have died from rupture prior to surgical intervention as the diameter was less than 5 cm, with 25% (116/473) of cases possibly undergoing unnecessary surgery since these AAAs may never have ruptured.[67]

Alternative methods of rupture assessment have been recently reported. The majority of these approaches involve the numerical analysis of AAAs using the common engineering technique of the finite element method (FEM) to determine the wall stress distributions. Recent reports have shown that these stress distributions have been shown to correlate to the overall geometry of the AAA rather than solely to the maximum diameter.[68][69][70] It is also known that wall stress alone does not completely govern failure as an AAA will usually rupture when the wall stress exceeds the wall strength. In light of this, rupture assessment may be more accurate if both the patient-specific wall stress is coupled together with patient-specific wall strength. A noninvasive method of determining patient-dependent wall strength was recently reported,[71] with more traditional approaches to strength determination via tensile testing performed by other researchers in the field.[72][73][74] Some of the more recently proposed AAA rupture-risk assessment methods include: AAA wall stress;[30][75][76] AAA expansion rate;[77] degree of asymmetry;[70] presence of intraluminal thrombus (ILT);[78] a rupture potential index (RPI);[79][80] a finite element analysis rupture index (FEARI);[81] biomechanical factors coupled with computer analysis;[82] growth of ILT;[83] geometrical parameters of the AAA;[84] and also a method of determining AAA growth and rupture based on mathematical models.[85][86]

The postoperative mortality for an already ruptured AAA has slowly decreased over several decades but remains higher than 40%.[87] However, if the AAA is surgically repaired before rupture, the postoperative mortality rate is substantially lower, approximately 1-6%.[88]

Epidemiology

The occurrence of AAA varies by ethnicity. In the United Kingdom, the rate of AAA in Caucasian men older than 65 years is about 4.7%, while in Asian men it is 0.45%.[89] It is also less common in individuals of African, and Hispanic heritage.[1] They occur four times more often in men than in women.[1]

There are at least 13,000 deaths yearly in the U.S. secondary to AAA rupture.[1] The peak number of new cases per year among males is around 70 years of age, and the percentage of males affected over 60 years is 2–6%. The frequency is much higher in smokers than in non-smokers (8:1), and the risk decreases slowly after smoking cessation.[90] In the U.S., the incidence of AAA is 2–4% in the adult population.[16]

Rupture of the AAA occurs in 1–3% of men aged 65 or more, for whom the mortality rate is 70–95%.[40]

History

The first historical records about AAA are from Ancient Rome in the 2nd century AD, when Greek surgeon Antyllus tried to treat the AAA with proximal and distal ligature, central incision and removal of thrombotic material from the aneurysm. However, attempts to treat the AAA surgically were unsuccessful until 1923. In that year, Rudolph Matas (who also proposed the concept of endoaneurysmorrhaphy), performed the first successful aortic ligation on a human.[91] Other methods that were successful in treating the AAA included wrapping the aorta with polyethene cellophane, which induced fibrosis and restricted the growth of the aneurysm. Endovascular aneurysm repair was first performed in the late 1980s and has been widely adopted in the subsequent decades. Endovascular repair was first used for treating a ruptured aneurysm in Nottingham in 1994.[92]

Society and culture

Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein underwent an operation for an abdominal aortic aneurysm in 1949 that was performed by Rudolph Nissen, who wrapped the aorta with polyethene cellophane. Einstein's aneurysm ruptured on April 13, 1955. He declined surgery, saying, "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly." He died five days later at age 76.[93]

Actress Lucille Ball died April 26, 1989, from an abdominal aortic aneurysm. At the time of her death, she was in Cedars-Sinai Medical Center recovering from emergency surgery performed just six days earlier because of a dissecting aortic aneurysm near her heart. Ball was at increased risk as she had been a heavy smoker for decades.[94]

Musician Conway Twitty died in June 1993 from an abdominal aortic aneurysm at the age of 59, two months before the release of what would be his final studio album, Final Touches.[citation needed]

Actor George C. Scott died in 1999 from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm at age 71.[citation needed]

In 2001, former presidential candidate Bob Dole underwent surgery for an abdominal aortic aneurysm in which a team led by vascular surgeon Kenneth Ouriel inserted a stent graft:[95]

| “ | Ouriel said that the team inserted a Y-shaped tube through an incision in Dole's leg and placed it inside the weakened portion of the aorta. The aneurysm will eventually contract around the stent, which will remain in place for the rest of Dole's life.[95] | ” |

— Associated Press

Actor Robert Jacks, who played Leatherface in Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation, died from an abdominal aneurysm on August 8, 2001, one day shy of his 42nd birthday. His father also died from the same cause when Jacks was a child.

Actor Tommy Ford died of abdominal aneurysm in October 2016 at 52 years old.[96]

Gary Gygax, co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, died in 2008 from an abdominal aortic aneurysm at the age of 69.

Research

Risk assessment

There have been many calls for alternative approaches to rupture risk assessment over the past number of years, with many believing that a biomechanics-based approach may be more suitable than the current diameter approach. Numerical modeling is a valuable tool to researchers allowing approximate wall stresses to be calculated, thus revealing the rupture potential of a particular aneurysm. Experimental models are required to validate these numerical results and provide a further insight into the biomechanical behavior of the AAA. In vivo, AAAs exhibit a varying range of material strengths[97] from localised weak hypoxic regions[98] to much stronger regions and areas of calcifications.[99]

Finding ways to predict future AAA growth is seen as a research priority.[100]

Another related line of research is utilizing mathematical decision modeling (e.g., Markov decision processes) to determine improved treatment policies. Initial results suggest that a more dynamic policy could provide benefits, although such claims have not been clinically verified.[101][102]

Experimental models

Experimental models can now be manufactured using a novel technique involving the injection-moulding lost-wax manufacturing process to create patient-specific anatomically correct AAA replicas.[103] Work has also focused on developing more realistic material analogues to those in vivo, and recently a novel range of silicone-rubbers was created allowing the varying material properties of the AAA to be more accurately represented.[104] These rubber models can also be used in a variety of experimental situations, from stress analysis using the photoelastic method[105] New endovascular devices are being developed that are able to treat more complex and tortuous anatomies.[106]

Prevention and treatment

An animal study showed that removing a single protein prevents early damage in blood vessels from triggering a later-stage, complications. By eliminating the gene for a signaling protein called cyclophilin A (CypA) from a strain of mice, researchers were able to provide complete protection against abdominal aortic aneurysm.[107]

Other recent research identified Granzyme B (GZMB) (a protein-degrading enzyme) to be a potential target in the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Elimination of this enzyme in mice models both slowed the progression of aneurysms and improved survival.[108][109]

Preclinical Research

The mechanisms that lead to AAA development are still not completely understood at a cellular and molecular level. In order to better understand the pathophysiology of AAA, it is often necessary to use experimental animal models. It is often questioned how well do these models translate to human disease. Even though there is no animal model that exactly represents the human condition, all the existing ones focus on one different pathophysiological aspect of the disease. Combining the results from different animal models with clinical research can provide a better overview of the AAA pathophysiology. The most common animal models are rodents (mice and rats), although for certain studies, such as testing preclinical devices or surgical procedures, large animal models (pig, sheep) are more frequently used. The rodent models of AAA can be classified according to different aspects. There are dissecting models vs non-dissecting models and genetically determined models vs chemically induced models. The most commonly used models are the angiotensin-II infusion into ApoE knockout mice (dissecting model, chemically induced), the calcium chloride model (non-dissecting, chemically induced) and the elastase model (non-dissecting, chemically induced model).[110][111] A recent study has shown that β-Aminopropionitrile plus elastase application to abdominal aorta causes more severe aneurysm in mice as compared to elastase alone.[112]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 Kent KC (27 November 2014). "Clinical practice. Abdominal aortic aneurysms.". The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (22): 2101–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1401430. PMID 25427112.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Abdominal aortic aneurysm". Am Fam Physician 73 (7): 1198–204. 2006. PMID 16623206.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wittels K (November 2011). "Aortic emergencies.". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 29 (4): 789–800, vii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.09.015. PMID 22040707.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Aortic Aneurysm Fact Sheet". July 22, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_aortic_aneurysm.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 ((GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators)) (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Abdominal emergencies in the geriatric patient.". International Journal of Emergency Medicine 7 (1): 43. 2014. doi:10.1186/s12245-014-0043-2. PMID 25635203.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 LeFevre ML (19 August 2014). "Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement.". Annals of Internal Medicine 161 (4): 281–90. doi:10.7326/m14-1204. PMID 24957320.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Svensjö, S; Björck, M; Wanhainen, A (December 2014). "Update on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a topical review.". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 48 (6): 659–67. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.08.029. PMID 25443524.

- ↑ "Open versus Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in the Elective and Emergent Setting in a Pooled Population of 37,781 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". ISRN Cardiology 2014: 149243. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/149243. PMID 25006502.

- ↑ "Elective endovascular vs. open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients aged 80 years and older: systematic review and meta-analysis.". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 42 (5): 571–6. November 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.07.011. PMID 21820922.

- ↑ "Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1 (1): CD004178. 23 January 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004178.pub2. PMID 24453068.

- ↑ "Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) follow-up imaging: the assessment and treatment of common postoperative complications.". Clinical Radiology 70 (2): 183–196. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2014.09.010. PMID 25443774.

- ↑ Bunce, Nicholas H.; Ray, Robin; Patel, Hitesh (2020). "30. Cardiology". in Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (in en). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1129–1130. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=sl3sDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1129.

- ↑ ((GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators)) (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ Fauci, Anthony (2008-03-06). "242". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-146633-2.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm at eMedicine

- ↑ "Risk Factors for Aneurysm Rupture in Patients Kept Under Ultrasound Surveillance". Annals of Surgery 230 (3): 289–96; discussion 296–7. September 1999. doi:10.1097/00000658-199909000-00002. PMID 10493476.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Treska V. et al.:Aneuryzma břišní aorty, Prague, 1999, ISBN:80-7169-724-9

- ↑ Goldman, Lee (2011-07-25). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 837. ISBN 978-1437727883.

- ↑ "Abdominal aortic aneurysm". Am Fam Physician 91 (8): 538–43. April 2015. PMID 25884861.

- ↑ "Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (5): 494–501. January 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0707524. PMID 18234753.

- ↑ "Sibling risks of abdominal aortic aneurysm". Lancet 346 (8975): 601–4. Sep 1995. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91436-6. PMID 7651004.

- ↑ Clifton MA (Nov 1977). "Familial abdominal aortic aneurysms". Br J Surg 64 (11): 765–6. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800641102. PMID 588966.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ Conley, Buford R.; Doux, John D.; Lee, Patrick Y.; Bazar, Kimberly A.; Daniel, Stephanie M.; Yun, Anthony J. (2005-01-01). "Integrating the theories of Darwin and Bernoulli: Maladaptive baroreceptor network dysfunction may explain the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysms" (in en). Medical Hypotheses 65 (2): 266–272. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.03.006. ISSN 0306-9877. PMID 15922098. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306987705001507.

- ↑ "Perforin-independent extracellular granzyme B activity contributes to abdominal aortic aneurysm". Am. J. Pathol. 176 (2): 1038–49. 2010. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090700. PMID 20035050.

- ↑ "Serpina3n attenuates granzyme B-mediated decorin cleavage and rupture in a murine model of aortic aneurysm". Cell Death Dis 2 (9): e209. 2011. doi:10.1038/cddis.2011.88. PMID 21900960.

- ↑ "Pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm". Br J Surg 81 (7): 935–41. 1994. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800810704. PMID 7922083.

- ↑ "Blood flow and coherent vortices in the normal and aneurysmatic aortas: a fluid dynamical approach to intra-luminal thrombus formation". J R Soc Interface 8 (63): 1449–61. 2011. doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0041. PMID 21471188.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Prediction of rupture risk in abdominal aortic aneurysm during observation: wall stress versus diameter". Journal of Vascular Surgery 37 (4): 724–32. April 2003. doi:10.1067/mva.2003.213. PMID 12663969.

- ↑ Chung, Timothy K.; Gueldner, Pete H.; Kickliter, Trevor M.; Liang, Nathan L.; Vorp, David A. (November 2022). "An Objective and Repeatable Sac Isolation Technique for Comparing Biomechanical Metrics in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms" (in en). Bioengineering 9 (11): 601. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9110601. ISSN 2306-5354. PMID 36354512.

- ↑ "Biomechanical rupture risk assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: model complexity versus predictability of finite element simulations". Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 40 (2): 176–185. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.04.003. PMID 20447844.

- ↑ "VASCOPS". http://www.vascops.com/en/vascops-A4clinics.html.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Canchi, Tejas; Patnaik, Sourav S.; Nguyen, Hong N.; Ng, E. Y. K.; Narayanan, Sriram; Muluk, Satish C.; De Oliveira, Victor; Finol, Ender A. (2020-06-01). "A Comparative Study of Biomechanical and Geometrical Attributes of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in the Asian and Caucasian Populations". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 142 (6). doi:10.1115/1.4045268. ISSN 1528-8951. PMID 31633169.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Rengarajan, Balaji; Patnaik, Sourav S.; Finol, Ender A. (2021-12-01). "A Predictive Analysis of Wall Stress in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Using a Neural Network Model". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 143 (12). doi:10.1115/1.4051905. ISSN 1528-8951. PMID 34318314.

- ↑ "Regions of high wall stress can predict the future location of rupture in abdominal aortic aneurysm". Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 37 (3): 815–818. 2014. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0864-7. PMID 24554200.

- ↑ Timothy Jang (2017-08-28). "Bedside Ultrasonography Evaluation of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm - Technique". https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1977715-overview#a3.

- ↑ "UOTW #35 - Ultrasound of the Week". 27 January 2015. https://www.ultrasoundoftheweek.com/uotw-35/.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Lumb, Philip (2014-01-16). Overview of the Arterial System. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323278171. https://books.google.com/books?id=zbydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA56. Retrieved 2017-08-23. Page 56 in: Philip Lumb (2014). Critical Care Ultrasound E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323278171.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: single centre randomised controlled trial". BMJ 330 (7494): 750. Apr 2005. doi:10.1136/bmj.38369.620162.82. PMID 15757960.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Hirsch, Alan T.; Haskal, Ziv J.; Hertzer, Norman R.; Bakal, Curtis W.; Creager, Mark A.; Halperin, Jonathan L.; Hiratzka, Loren F.; Murphy, William R.C. et al. (September 2006). "ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (Lower Extremity, Renal, Mesenteric, and Abdominal Aortic)". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 17 (9): 1383–1398. doi:10.1097/01.RVI.0000240426.53079.46. PMID 16990459.

- ↑ Kent, K. Craig (27 November 2014). "Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms". New England Journal of Medicine 371 (22): 2101–2108. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1401430. PMID 25427112.

- ↑ Jeffrey Jim, Robert W Thompson (2018-03-05). "Clinical features and diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm". https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-abdominal-aortic-aneurysm.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 US Preventive Services Task, Force.; Owens, DK; Davidson, KW; Krist, AH; Barry, MJ; Cabana, M; Caughey, AB; Doubeni, CA et al. (10 December 2019). "Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.". JAMA 322 (22): 2211–2218. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.18928. PMID 31821437.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Ali, MU; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D; Miller, J; Warren, R; Kenny, M; Sherifali, D; Raina, P (December 2016). "Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in asymptomatic adults.". Journal of Vascular Surgery 64 (6): 1855–1868. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.05.101. PMID 27871502.

- ↑ "NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme". https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/617871/AAA_draft_short_form_decision_aid.pdf.

- ↑ "Aortascreening av nära släkting (Aortic screening of close relative)". https://alfresco.vgregion.se/alfresco/service/vgr/storage/node/content/6861/Aortascreening%20av%20n%C3%A4ra%20sl%C3%A4kting.pdf?a=false&guest=true.

- ↑ Robinson, Domenic; Mees, Barend; Verhagen, Hence; Chuen, Jason (June 2013). "Aortic aneurysms – screening, surveillance and referral.". Australian Family Physician 42 (6): 364–9. PMID 23781541.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Surveillance intervals for small abdominal aortic aneurysms: a meta-analysis". JAMA 309 (8): 806–13. February 2013. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.950. PMID 23443444. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/JAMA/926459/joc130012_806_813.pdf.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Ulug, Pinar; Powell, Janet T; Martinez, Melissa Ashley-Marie; Ballard, David J; Filardo, Giovanni (1 July 2020). "Surgery for small asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020 (7): CD001835. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001835.pub5. PMID 32609382.

- ↑ Timmers, Tim K.; van Herwaarden, Joost A.; de Borst, Gert-Jan; Moll, Frans L.; Leenen, Luke P. H. (December 2013). "Long-Term Survival and Quality of Life After Open Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair". World Journal of Surgery 37 (12): 2957–2964. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2206-3. PMID 24132818.

- ↑ Premnath, Sivaram; Zaver, Vasudev; Hostalery, Aurelien; Rowlands, Timothy; Quarmby, John; Singh, Sanjay (2021-07-01). "Mycotic Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms – A Tertiary Centre Experience and Formulation of a Management Protocol" (in English). Annals of Vascular Surgery 74: 246–257. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2020.12.025. ISSN 0890-5096. PMID 33508457. https://www.annalsofvascularsurgery.com/article/S0890-5096(21)00079-0/abstract.

- ↑ "Final 12-year follow-up of surgery versus surveillance in the UK Small Aneurysm Trial". Br J Surg 94 (6): 702–8. Jun 2007. doi:10.1002/bjs.5778. PMID 17514693.

- ↑ "Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms". N Engl J Med 346 (19): 1437–44. May 2002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012573. PMID 12000813.

- ↑ Rutherford RB (Jun 2006). "Randomized EVAR trials and advent of level i evidence: a paradigm shift in management of large abdominal aortic aneurysms?". Semin Vasc Surg 19 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2006.03.001. PMID 16782510.

- ↑ "Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm". Annals of Internal Medicine 146 (10): 735–41. 2007. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00007. PMID 17502634.

- ↑ Evar Trial Participants (2005). "Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial". Lancet 365 (9478): 2179–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66627-5. PMID 15978925.

- ↑ "Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms". N Engl J Med 352 (23): 2398–405. Jun 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051255. PMID 15944424.

- ↑ Evar Trial Participants (2005). "Endovascular aneurysm repair and outcome in patients unfit for open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 2): randomised controlled trial". Lancet 365 (9478): 2187–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66628-7. PMID 15978926.

- ↑ "Endovascular treatment of a triple paraanastomotic aneurysm after aortobiiliac reconstruction". Jornal Vascular Brasileiro 7 (3): 1–3. 2008. doi:10.1590/S1677-54492008000300016.

- ↑ Badger, Stephen; Forster, Rachel; Blair, Paul H; Ellis, Peter; Kee, Frank; Harkin, Denis W (26 May 2017). "Endovascular treatment for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 (6): CD005261. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005261.pub4. PMID 28548204.

- ↑ Hamilton, H; Constantinou, J; Ivancev, K (April 2014). "The role of permissive hypotension in the management of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms". The Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 55 (2): 151–159. PMID 24670823. https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/cardiovascular-surgery/article.php?cod=R37Y2014N02A0151.

- ↑ "Abdominal aortic aneurysm in high-risk patients. Outcome of selective management based on size and expansion rate". Ann. Surg. 200 (3): 255–63. September 1984. doi:10.1097/00000658-198409000-00003. PMID 6465980.

- ↑ "Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery". J. Vasc. Surg. 37 (5): 1106–17. May 2003. doi:10.1067/mva.2003.363. PMID 12756363.

- ↑ "Autopsy study of unoperated abdominal aortic aneurysms. The case for early resection". Circulation 56 (3 Suppl): II161–4. September 1977. PMID 884821.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Rupture in small abdominal aortic aneurysms". Journal of Vascular Surgery 28 (5): 884–8. November 1998. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70065-5. PMID 9808857.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Vorp DA (2007). "Biomechanics of abdominal aortic aneurysm". Journal of Biomechanics 40 (9): 1887–902. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.003. PMID 17254589.

- ↑ "Mechanical wall stress in abdominal aortic aneurysm: influence of diameter and asymmetry". Journal of Vascular Surgery 27 (4): 632–9. April 1998. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70227-7. PMID 9576075.

- ↑ "In vivo three-dimensional surface geometry of abdominal aortic aneurysms". Annals of Biomedical Engineering 27 (4): 469–79. 1999. doi:10.1114/1.202. PMID 10468231.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "Vessel Asymmetry as an Additional Diagnostic Tool in the Assessment of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms". Journal of Vascular Surgery 49 (2): 443–54. February 2009. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.064. PMID 19028061.

- ↑ "Towards A Noninvasive Method for Determination of Patient-Specific Wall Strength Distribution in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms". Annals of Biomedical Engineering 34 (7): 1098–1106. 2006. doi:10.1007/s10439-006-9132-6. PMID 16786395.

- ↑ "Regional distribution of wall thickness and failure properties of human abdominal aortic aneurysm". Journal of Biomechanics 39 (16): 3010–6. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.021. PMID 16337949.

- ↑ "Ex vivo biomechanical behavior of abdominal aortic aneurysm: assessment using a new mathematical model". Annals of Biomedical Engineering 24 (5): 573–82. 1996. doi:10.1007/BF02684226. PMID 8886238.

- ↑ "Mechanical properties of abdominal aortic aneurysm wall". Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology 25 (4): 133–42. 2001. doi:10.1080/03091900110057806. PMID 11601439.

- ↑ "In vivo analysis of mechanical wall stress and abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture risk". Journal of Vascular Surgery 36 (3): 589–97. September 2002. doi:10.1067/mva.2002.125478. PMID 12218986.

- ↑ "A comparative study of aortic wall stress using finite element analysis for ruptured and non-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 28 (2): 168–76. August 2004. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.03.029. PMID 15234698.

- ↑ "Growth curve of ruptured aortic aneurysm". The Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 39 (1): 9–13. February 1998. PMID 9537528.

- ↑ "Effect of intraluminal thrombus on wall stress in patient-specific models of abdominal aortic aneurysm". Journal of Vascular Surgery 36 (3): 598–604. September 2002. doi:10.1067/mva.2002.126087. PMID 12218961.

- ↑ "Biomechanical determinants of abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 25 (8): 1558–66. August 2005. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000174129.77391.55. PMID 16055757.

- ↑ "A biomechanics-based rupture potential index for abdominal aortic aneurysm risk assessment". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1085 (1): 11–21. 2006. doi:10.1196/annals.1383.046. PMID 17182918. Bibcode: 2006NYASA1085...11V.

- ↑ Doyle, Barry J.; Callanan, Anthony; Walsh, Michael T.; Grace, Pierce A.; McGloughlin, Timothy M. (11 July 2009). "A Finite Element Analysis Rupture Index (FEARI) as an Additional Tool for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Rupture Prediction". Vascular Disease Prevention 6 (1): 114–121. doi:10.2174/1567270001006010114.

- ↑ "Analysis and computer program for rupture-risk prediction of abdominal aortic aneurysms". BioMedical Engineering OnLine 5 (1): 19. 2006. doi:10.1186/1475-925X-5-19. PMID 16529648.

- ↑ "Growth of thrombus may be a better predictor of rupture than diameter in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 20 (5): 466–9. November 2000. doi:10.1053/ejvs.2000.1217. PMID 11112467.

- ↑ "Predicting the risk of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms by utilizing various geometrical parameters: revisiting the diameter criterion". Angiology 57 (4): 487–94. 2006. doi:10.1177/0003319706290741. PMID 17022385.

- ↑ "A mathematical model for the growth of the abdominal aortic aneurysm". Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology 3 (2): 98–113. November 2004. doi:10.1007/s10237-004-0052-9. PMID 15452732.

- ↑ "A model of growth and rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm". Journal of Biomechanics 41 (5): 1015–21. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.12.014. PMID 18255074.

- ↑ "A meta-analysis of 50 years of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair". The British Journal of Surgery 89 (6): 714–30. June 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02122.x. PMID 12027981.

- ↑ "Comparison of endovascular aneurysm repair with open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1), 30-day operative mortality results: randomised controlled trial". Lancet 364 (9437): 843–8. 2004. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16979-1. PMID 15351191.

- ↑ "Should Asian men be included in abdominal aortic aneurysm screening programmes?". Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 38 (6): 748–9. December 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.07.012. PMID 19666232.

- ↑ "The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms". J Vasc Surg 30 (6): 1099–105. Dec 1999. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70049-2. PMID 10587395.

- ↑ "Milestones in Treatment of Aortic Aneurysm: Denton A. Cooley, MD, and the Texas Heart Institute". Tex Heart Inst J 32 (2): 130–4. 2005. PMID 16107099.

- ↑ "Emergency endovascular repair of leaking aortic aneurysm". Lancet 344 (8937): 1645. December 1994. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90443-X. PMID 7984027.

- ↑ Lowenfels, Albert B. (14 June 2002). "Famous Patients, Famous Operations, Part 3". Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/436253.

- ↑ Ball, Lucille (April 27, 1989). "Ball dies of ruptured aorta". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1989-04-27/news/mn-1618_1_love-lucy-aorta-emergency-heart-surgery.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "Bob Dole has surgery to treat aneurysm". USA Today via Associated Press. 2001-06-27. https://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/june01/2001-06-27-dole.htm.

- ↑ Mele, Christopher (12 October 2016). "Thomas Mikal Ford, Known for His Role in '90s Sitcom 'Martin,' Dies at 52". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/13/arts/television/thomas-mikal-ford-costar-of-martin-dies.html.

- ↑ "Regional distribution of wall thickness and failure properties of human abdominal aortic aneurysm". J. Biomech 39 (16): 3010–3016. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.021. PMID 16337949.

- ↑ "Association of intraluminal thrombus in abdominal aortic aneurysm with local hypoxia and wall weakening". Journal of Vascular Surgery 34 (2): 291–299. 2001. doi:10.1067/mva.2001.114813. PMID 11496282.

- ↑ "Effects of wall calcifications in patient-specific wall stress analyses of abdominal aortic aneurysms". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 129 (1): 105–109. 2007. doi:10.1115/1.2401189. PMID 17227104.

- ↑ Lee, Regent; Jones, Amy; Cassimjee, Ismail; Handa, Ashok; Oxford Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Study. (October 2017). "International opinion on priorities in research for small abdominal aortic aneurysms and the potential path for research to impact clinical management". International Journal of Cardiology 245: 253–255. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.06.058. PMID 28874296. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c8773f49-d2a4-44f2-9957-510d39b9d476.

- ↑ Mattila, Robert; Siika, Antti; Roy, Joy; Wahlberg, Bo (2016). "A Markov decision process model to guide treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms". 2016 IEEE Conference on Control Applications (CCA). pp. 436–441. doi:10.1109/CCA.2016.7587869. ISBN 978-1-5090-0755-4. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7587869.

- ↑ Grant, Stuart; Sperrin, Matthew; Carlson, Eric; Chinai, Natasha; Ntais, Dionysios; Hamilton, Matthew; Dunn, Graham; Bunchan, Iain et al. (2015). "Calculating when elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair improves survival for individual patients: development of the Aneurysm Repair Decision Aid and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment 19 (32): 1–154. doi:10.3310/hta19320. PMID 25924187. PMC 4781543. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta19320/#/abstract.

- ↑ Doyle, B. J.; Morris, L. G.; Callanan, A.; Kelly, P.; Vorp, D. A.; McGloughlin, T. M. (1 June 2008). "3D Reconstruction and Manufacture of Real Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: From CT Scan to Silicone Model". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 130 (3): 034501. doi:10.1115/1.2907765. PMID 18532870.

- ↑ Doyle, Barry J.; Corbett, Timothy J.; Cloonan, Aidan J.; O'Donnell, Michael R.; Walsh, Michael T.; Vorp, David A.; McGloughlin, Timothy M. (October 2009). "Experimental modelling of aortic aneurysms: Novel applications of silicone rubbers". Medical Engineering & Physics 31 (8): 1002–1012. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.06.002. PMID 19595622.

- ↑ Doyle, Barry J.; Corbett, Timothy J.; Callanan, Anthony; Walsh, Michael T.; Vorp, David A.; McGloughlin, Timothy M. (June 2009). "An Experimental and Numerical Comparison of the Rupture Locations of an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm". Journal of Endovascular Therapy 16 (3): 322–335. doi:10.1583/09-2697.1. PMID 19642790.

- ↑ Albertini, JN; Perdikides, T; Soong, CV; Hinchliffe, RJ; Trojanowska, M; Yusuf, SW (June 2006). "Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with severe angulation of the proximal neck using a flexible stent-graft: European Multicenter Experience.". The Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 47 (3): 245–250. ProQuest 224419745. PMID 16760860. https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/cardiovascular-surgery/article.php?cod=R37Y2006N03A0245.

- ↑ "Study establishes major new treatment target in diseased arteries". U.S. News & World Report. May 10, 2009. http://www.physorg.com/news161183060.html.

- ↑ "Perforin-Independent Extracellular Granzyme B Activity Contributes to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm". The American Journal of Pathology 176 (2): 1038–1049. 2010. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090700. PMID 20035050.

- ↑ "Discovery points way for new treatment for aneurysms". University of British Columbia. January 27, 2010. http://www.hli.ubc.ca/news_events/news.php?user=events&index=1&count=1&date=20100101.

- ↑ Sénémaud, Jean; Caligiuri, Giuseppina; Etienne, Harry; Delbosc, Sandrine; Michel, Jean-Baptiste; Coscas, Raphaël (March 2017). "Translational Relevance and Recent Advances of Animal Models of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm" (in en). Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 37 (3): 401–410. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308534. ISSN 1079-5642. PMID 28062500.

- ↑ Daugherty, Alan; Cassis, Lisa A. (2004-03-01). "Mouse Models of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 24 (3): 429–434. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000118013.72016.ea. PMID 14739119.

- ↑ Berman, Alycia G.; Romary, Daniel J.; Kerr, Katherine E.; Gorazd, Natalyn E.; Wigand, Morgan M.; Patnaik, Sourav S.; Finol, Ender A.; Cox, Abigail D. et al. (2022-01-07). "Experimental aortic aneurysm severity and growth depend on topical elastase concentration and lysyl oxidase inhibition". Scientific Reports 12 (1): 99. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04089-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 34997075. Bibcode: 2022NatSR..12...99B.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

de:Aortenaneurysma#Bauchaortenaneurysma

|

![Aortic measurement on abdominal ultrasonography in the axial plane between the outer margins of the aortic wall[37]](/wiki/images/thumb/7/7b/Ultrasonographic_measurement_of_aortic_diameter_at_the_navel.svg/120px-Ultrasonographic_measurement_of_aortic_diameter_at_the_navel.svg.png)