Medicine:Adenosine deaminase deficiency

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | ADA deficiency, ADA-SCID, and Severe combined immunodeficiency due to ADA deficiency |

| |

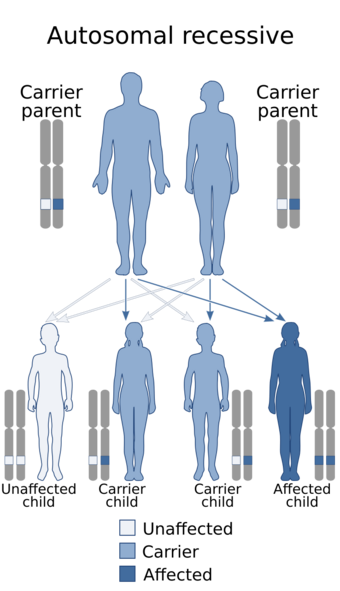

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. | |

Adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA deficiency) is a metabolic disorder that causes immunodeficiency. It is caused by mutations in the ADA gene. It accounts for about 10–20% of all cases of autosomal recessive forms of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) after excluding disorders related to inbreeding.[1][2]

ADA deficiency can present in infancy, childhood, adolescence, or adulthood. Age of onset and severity is related to some 29 known genotypes associated with the disorder.[3] It occurs in fewer than one in 100,000 live births worldwide.

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms of ADA deficiency include pneumonia, chronic diarrhea, widespread skin rashes, jaundice (from hepatic infections), and candidiasis of the mouth and esophagus. Affected children also grow much more slowly than healthy children, commonly referred to as "failure to thrive," which may lead to other developmental delays.[4]

These symptoms are not due to the enzyme deficiency itself, but rather to the effects of frequent severe infections from viruses, bacteria, and certain fungi.[4] Children are particularly vulnerable to repeated infections from the same organisms, as their lack of B-cells means they cannot produce IgG antibodies in significant amounts, which protect most people from pathogens that have infected them before.[5] Most individuals with ADA deficiency are diagnosed with SCID in the first 6 months of life.[6]

The large majority of cases of ADA deficiency are identified and diagnosed in children. However, a small minority have a less-severe form of the disease and remain undiagnosed until childhood, adolescence, or adulthood.[4][6]

An association with polyarteritis nodosa has been reported.[7]

Genetics

The enzyme adenosine deaminase is encoded by the ADA gene on chromosome 20.[1] ADA deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This means the defective gene responsible for the disorder is located on an autosome (chromosome 20 is an autosome), and two copies of the defective gene (one inherited from each parent) are required in order to be born with the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder both carry one copy of the defective gene, but usually do not experience any signs or symptoms of the disorder.[4][8]

Age of onset and severity is related to some 29 known genotypes associated with the disorder.[3]

Pathophysiology

ADA deficiency is due to a lack of the enzyme adenosine deaminase. This deficiency results in an accumulation of deoxyadenosine,[2][9] which, in turn, leads to:

- A buildup of dATP in all cells, which inhibits ribonucleotide reductase and prevents DNA synthesis, so cells are unable to divide. Since developing T cells and B cells are some of the most mitotically active cells, they are highly susceptible to this condition.

- An increase in S-adenosylhomocysteine since the enzyme adenosine deaminase is important in the purine salvage pathway; both substances are toxic to immature lymphocytes, which thus fail to mature.

- Complete or near-complete absence of T-cells, B-cells, and NK cells.[2]

Because T cells undergo proliferation and development in the thymus, affected individuals typically have a small, underdeveloped thymus.[10] As a result, the immune system is severely compromised or completely lacking.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis in developed nations is usually done through standardized newborn screening tests for a range of congenital diseases, including ADA deficiency. Most newborns with SCID, including those with ADA deficiency as an underlying cause, can be identified before the onset of major infections due to their decreased levels of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs). TRECs are a normal product of T-cell development, and a deficit of them indicates a problem with lymphocyte maturation.[4]

In the absence of newborn screening or to differentiate from other causes of SCID, some (but not all) children will display one or more of these features which are sometimes seen in ADA deficiency but not other forms of SCID:[4]

- Earlier onset of failure to thrive

- Respiratory distress in an infant that is not caused by an infection

- Abnormal rib cage development

- Neurologic disorders, especially hearing loss

When ADA deficiency is suspected, the diagnosis may be confirmed through several lab tests of the patient's red blood cells, or via genetic testing.[4]

Treatment

Treatment of ADA deficiency focuses on reducing the frequency and severity of infections. Antibiotics are typically prescribed as a prophylactic measure to make the body more difficult for pathogenic organisms to colonize. Due to the frequency it is encountered and its indifference to most antibiotics, clinicians must be careful to include a medication that can prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia.[11]

In addition to antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy is also provided when available. This treatment provides a layer of humoral immunity from healthy plasma donors.[11]

Enzyme replacement therapy is provided to newborns until a definitive therapy plan can be implemented.[11] There is some evidence that ERT also prevents tissue damage related to accumulated dATP and other molecules.[12]

Stem cell transplantation

Long-term definitive treatment of ADA deficiency is typically achieved by transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells from a matched family member donor, preferably a sibling. Before transplantation, testing must be done to ensure that human leukocyte antigen (HLA) properties of the donor and the transplant recipient align, to avoid transplant rejection.[11]

Gene therapy

The other definitive therapy available for ADA deficiency is gene therapy. These therapies use a viral vector to integrate a working copy of the gene into the patient's genome.[11]

In September 1990, the first gene therapy to combat this disease was performed by Dr. William French Anderson on a four-year-old girl, Ashanti DeSilva, at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A.[13] In April 2016 the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency endorsed and recommended for approval a stem cell gene therapy called Strimvelis, for children with ADA-SCID for whom no matching bone marrow donor is available.[14][15]

History

ADA deficiency was discovered in 1972 by Eloise Giblett, a professor at the University of Washington.[16] The ADA gene was used as a marker for bone marrow transplants. A lack of ADA activity was discovered by Giblett in an immunocompromised transplant candidate. After discovering a second case of ADA deficiency in an immunocompromised patient, ADA deficiency was recognized as the first immunodeficiency disorder.[16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Adenosine deaminase deficiency: a review". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 13 (1): 65. April 2018. doi:10.1186/s13023-018-0807-5. PMID 29690908.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Chapter 351: Primary Immune Deficiency Diseases" (in English). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (21st ed.). McGraw Hill. 2022. ISBN 978-1264268504.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Adenosine deaminase deficiency: genotype-phenotype correlations based on expressed activity of 29 mutant alleles". American Journal of Human Genetics 63 (4): 1049–1059. October 1998. doi:10.1086/302054. PMID 9758612.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Adenosine deaminase deficiency: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. September 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/adenosine-deaminase-deficiency-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis.

- ↑ "Adenosine Deaminase Deficiency - More Than Just an Immunodeficiency". Frontiers in Immunology 7: 314. 2016-08-16. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00314. PMID 27579027.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Adult onset immunodeficiency caused by inherited adenosine deaminase deficiency". Journal of Immunology 153 (5): 2331–2339. September 1994. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.153.5.2331. PMID 8051429.

- ↑ "Thirty Years of Followup in 3 Patients with Familial Polyarteritis Nodosa due to Adenosine Deaminase 2 Deficiency". The Journal of Rheumatology 46 (8): 1059–1060. August 2019. doi:10.3899/jrheum.180820. PMID 31092714.

- ↑ "Carrier frequency of a nonsense mutation in the adenosine deaminase (ADA) gene implies a high incidence of ADA-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in Somalia and a single, common haplotype indicates common ancestry". Annals of Human Genetics 71 (Pt 3): 336–347. May 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00338.x. PMID 17181544.

- ↑ "Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) Deficiency". Genetic Science Learning Center. The University of Utah. http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/units/disorders/whataregd/ada/.

- ↑ The Immune System (3rd ed.). London and New York: Garland Science. 2009. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-415-95590-4.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Adenosine deaminase deficiency: Treatment and prognosis". Wolters Kluwer. July 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/adenosine-deaminase-deficiency-treatment-and-prognosis.

- ↑ "Consensus approach for the management of severe combined immune deficiency caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 143 (3): 852–863. March 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.024. PMID 30194989.

- ↑ "'More Than Human' - New York Times". The New York Times. 2005-07-03. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/03/books/chapters/0703-1st-naam.html.

- ↑ "European Ad Comm backs Glaxo's stem cell therapy Strimvelis for rare autoimmune disorder". Seeking Alpha. 1 April 2016. http://seekingalpha.com/news/3171007-european-ad-comm-backs-glaxos-stem-cell-therapy-strimvelis-rare-autoimmune-disorder.

- ↑ "Summary of opinion1 (initial authorisation) Strimvelis". 1 April 2016. pp. 1–2. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/003854/WC500203918.pdf.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Biographical Memoirs: Eloise R. Giblett". National Academy of Sciences. 2009. https://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/giblett-eloise.pdf.

Further reading

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|