Medicine:Adrenal crisis

| Adrenal crisis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute adrenal insufficiency, Addisonian crisis, Acute adrenal failure.[1] |

| |

| 49-year-old with an adrenal crisis. Appearance, showing lack of facial hair, dehydration, Queen Anne's sign (panel A), pale skin, muscular and weight loss, and loss of body hair (panel B). | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Dizziness, somnolence, confusion, loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased appetite, extreme exhaustion, unintended weight loss, weakness, and hypotension.[4] |

| Complications | Seizures, arrhythmias, organ damage, coma, and death.[4] |

| Causes | Adrenal insufficiency, thyrotoxicosis, infections, trauma, pregnancy, and surgery.[4] |

| Risk factors | Adrenal insufficiency, polyglandular autoimmune syndromes, glucocorticoids, levothyroxine, and rifampin.[4] |

| Diagnostic method | ACTH, basic metabolic panel, and cortisol.[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Myocardial infarction, trauma, stress, myxedema coma, circulatory shock, septic shock, and infection.[4] |

| Prevention | Providing intramuscular hydrocortisone at home and using sick day rules.[4] |

| Treatment | Steroid replacement and fluid resuscitation.[5] |

| Medication | Hydrocortisone.[4] |

| Prognosis | 6% mortality rate.[6] |

| Frequency | 6–8% of those with adrenal insufficiency annually.[7] |

Adrenal crisis, also known as Addisonian crisis or Acute adrenal insufficiency, is a serious, life-threatening complication of adrenal insufficiency. Hypotension, or hypovolemic shock, is the main symptom of adrenal crisis, other indications and symptoms include weakness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, fatigue, abnormal electrolytes, confusion, and coma.[8] Laboratory testing may detect lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and on occasion, hypercalcemia.[9]

Over 90% of adrenal crisis cases have a known precipitating event. Generally speaking, the biggest trigger for adrenal crisis is gastrointestinal illness.[10] The physiological mechanisms underlying an adrenal crisis involve the loss of endogenous glucocorticoids' typical inhibitory effect on inflammatory cytokines.[9]

When a patient with adrenal insufficiency exhibits symptoms of an adrenal crisis, treatment should begin immediately.[11] To diagnose an adrenal crisis, serum cortisol, aldosterone, ACTH, renin, and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate.[8] A low cortisol level of less than 5 mg/dL (138 nmol/L), measured in the early morning or during a stressful period, suggests a diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency.[12]

A tailored prescription, as well as a strategy for administering additional glucocorticoids for physiological stress, are critical preventative measures. If oral glucocorticoids are not an option, parenteral hydrocortisone, preferably at home, should be used. MedicAlert bracelets and necklaces, for example, can alert caregivers to the possibility of an adrenal crisis in patients who are unable to communicate verbally.[9] When an adult experiences an adrenal crisis, they require immediate parenteral hydrocortisone.[13]

About 6 to 8% of patients with adrenal insufficiency experience an adrenal crisis at some point each year.[7] The mortality rate linked to adrenal crises is up to 6%.[6]

Signs and symptoms

In as many as 50% of Addison's disease patients, adrenal crisis can be the first symptom of adrenal insufficiency.[14] Diagnosis is often delayed since most of the signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are nonspecific and develop insidiously. Symptoms include orthostatic hypotension, lethargy, fever, nausea, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal pain, weakness, hyperpigmentation, joint pain, and weight loss. Those in an adrenal crisis often go into hypotensive shock and may exhibit sensorium alterations. They often present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which can mistakenly be diagnosed as gastroenteritis or an acute abdomen.[5]

Glucocorticoids have a permissive effect on catecholamine action, which leads to hypotension secondary to hypovolemia and hypocortisolism.[15] Hypovolemia might be resistant to inotropes and fluids if it is not identified. In secondary adrenal insufficiency, Hyponatremia results from decreased kidney excretion of electrolyte-free water and the inability to suppress vasopressin.[16]

Hyponatremia in primary adrenal insufficiency is caused by concurrent aldosterone deficiency, resulting in volume depletion, natriuresis, and hyperkalemia.[17] Additional biochemical characteristics include hypercalcemia, which is a result of increased bone resorption and reduced renal excretion of calcium, and hypoglycemia, which occurs rarely.[18]

Causes

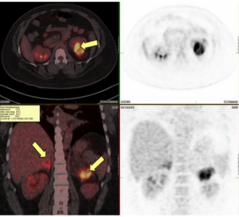

An absolute or relative lack of cortisol, which is an endogenous glucocorticoid, causes adrenal crises as there is not enough tissue glucocorticoid activity to preserve homeostasis.[9]

Exogenous steroid use is the most frequent cause of adrenal insufficiency, and patients who use these drugs also run the risk of experiencing an adrenal crisis.[11] Adrenal crisis can result from abrupt, and frequently unintentional, steroid withdrawal. Therefore, a thorough drug history is crucial, especially in cases of covert steroid use. The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis has been reported to be suppressed by the use of glucocorticoids in rectal,[19] paraspinal,[20] intradermal,[21] intraarticular,[22] injectable,[23] nasal,[24] inhaled,[25] or topical preparations.[26] At pharmacological dosages, medroxyprogesterone and megestrol also exhibit a notable glucocorticoid effect.[27] This risk may increase if steroids are used concurrently with ritonavir or, which inhibit the liver's CYP3A enzyme that breaks down steroids.[28][29]

Adrenal suppression is generally more likely with longer durations, greater doses, and oral and intraarticular preparations. Nonetheless, no amount, time frame, or mode of administration can reliably predict adrenal insufficiency.[30]

Risk factors

Because of the lack of mineralocorticoids and increased risk of dehydration and hypovolemia, those with primary adrenal insufficiency might be more susceptible to adrenal crisis compared to individuals with secondary adrenal insufficiency.[6]

Individuals with secondary adrenal insufficiency who have diabetes insipidus are more likely to experience an adrenal crisis. This increased risk could be attributed to either the absence of V1-receptor-mediated vasoconstriction throughout extreme stress or the increased risk of dehydration.[31] A higher risk of adrenal crisis has been linked in some studies to other medical conditions like hypogonadism[10] and type 1 and type 2 diabetes, though the exact mechanism is unknown.[32]

Patients with adrenal insufficiency have a 50% lifetime risk of experiencing an adrenal crisis,[32] and those who have experienced an adrenal crisis in the past seem to be more susceptible to another episode.[6]

Triggers

A known precipitating event can be found in over 90% of episodes of adrenal crisis.[5] The most common cause of adrenal crisis is almost always gastrointestinal illness. This is probably because it has a direct impact on how well oral glucocorticoids are absorbed through the intestines.[6] Stress from surgery is another common cause. Therefore, it's critical to monitor all patients closely during the procedure, administer stress medication as needed, and act quickly to stop a patient's condition from getting worse.[32]

Those who have autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2 might have concurrent thyroid and adrenal insufficiency. Levothyroxine can speed up the peripheral metabolism of cortisol and trigger an adrenal crisis in individuals with undetected adrenal insufficiency as well as those already on replacement.[33] Cytochrome P-450 enzyme inducers, such as phenobarbitone, rifampicin, and phenytoin, may trigger an adrenal crisis.[34] Therefore, glucocorticoid dosages should be appropriately increased in those with tuberculosis-associated adrenal insufficiency starting rifampicin.[35]

It is important to remember that an adrenal crisis can also be brought on by emotional stress in addition to physical stress.[6] Less frequent causes such as wasp bites, plane delays, and accidents show that patients must always be ready for the unexpected.[5] Patients with adrenal insufficiency must be advised to increase their exogenous intake of cortisol during illness or periods of extreme stress because they are unable to increase their endogenous production of the hormone.[32]

Mechanism

An absolute or relative lack of cortisol, an endogenous glucocorticoid, causes adrenal crises because there is not enough tissue glucocorticoid activity to preserve homeostasis in that situation.[9]

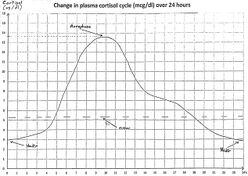

Since cortisol has a 90-minute half-life in the blood, tissues deplete several hours following cortisol deprivation.[36] Because cortisol modulates the transcription of genes containing a glucocorticoid response element, it has extremely pleiotropic effects.[37] The physiological effects of low cortisol begin with the loss of the natural inhibitory function of endogenous glucocorticoids on inflammatory cytokines. This leads to sharp rises in cytokine concentrations, which induce fever, lethargy, anorexia, and pain in the body. As a result, insufficient cortisol causes immune-cell populations to change, including lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, and neutropenia;[38] it also loses its ability to work in concert with catecholamines to reduce vascular reactivity, which causes vasodilatation and hypotension;[39] it has an adverse effect on the liver's intermediary metabolism, resulting in hypoglycemia, decreased gluconeogenesis, or both; and it lower levels of free fatty acids and amino acids in circulation.[40]

Loss of cortisol suppresses nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) at the cellular level, which allows genes that generate inflammatory proteins to be activated without restriction. This is because cortisol normally inhibits NF-κB's binding to the glucocorticoid receptor.[38] Additionally, through potassium retention and sodium and water loss, mineralocorticoid deficiency—which is common in primary but not in secondary adrenal insufficiency—is likely to aggravate adrenal crises.[31]

Diagnosis

When a patient with adrenal insufficiency is known to be exhibiting symptoms of an adrenal crisis, treatment needs to start right away. Treatment shouldn't be postponed in patients whose diagnosis is still pending to conduct diagnostic tests (such as an adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test) on a patient deemed medically unstable.[11]

Adrenal insufficiency can be diagnosed with renin, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, aldosterone, serum cortisol, and ACTH which can be taken right before hydrocortisone is administered. A high cortisol level of more than 20 mg/dL (550 nmol/L) can rule out the diagnosis.[8] A low cortisol level of less than 5 mg/dL (138 nmol/L), obtained in the early morning or during a stressful period, strongly suggests the possibility of adrenal insufficiency.[12] In instances of primary adrenal insufficiency, there is a correspondingly high ACTH level; in contrast, low or inappropriately normal ACTH correlates with tertiary or secondary adrenal insufficiency.[18]

When in doubt, the patient should receive glucocorticoid therapy until they have fully recovered, at which point a safe diagnostic test, like an ACTH stimulation test, can be performed. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis can be affected by prolonged glucocorticoid treatment, so this test should be done as soon as possible.[5]

Prevention

A customized prescription as well as a plan for the administration of additional glucocorticoids for physiological stress are important preventative measures. If oral glucocorticoids are not an option, parenteral hydrocortisone should be used, preferably at home. Devices like MedicAlert bracelets and necklaces can alert caregivers to the possibility of adrenal crisis in patients who are unable to communicate verbally.[9]

Although the exact dosage has been debated, it is generally agreed upon that all patients with proven adrenal insufficiency should receive glucocorticoid replacement during stressful times. The recommended amounts of glucocorticoid replacement are dependent on the anticipated stress, and the current guidelines depend on expert opinion.[41] Though there may be variations in specific regimens, most agree that stress doses for simple surgery should be quickly tapered and should not last longer than three days. This is because unneeded steroid excess can lead to infections, poor wound healing, and hyperglycemia.[5]

The recommendations are more irregular when it comes to medical stress because the clinical course is unpredictable and there is more disagreement about what constitutes a normal physiological response.[42] In those who are unable to tolerate oral medication or do not respond to stress doses, a low threshold to initiate parenteral hydrocortisone management should be used to guarantee adequate systemic absorption, since gastroenteritis frequently precedes an adrenal crisis[6] and a rise in oral glucocorticoids may not always avoid an adrenal crisis.[43] If necessary, doctors ought to think about administering extra doses in cases of extreme emotional stress (such as grief).[6]

Patients experiencing vomiting, chronic diarrhea, or an imminent adrenal crisis should receive intramuscular hydrocortisone. Patients must be prepared to administer it themselves because they can rapidly deteriorate.[41] A lot of patients may own a hydrocortisone ampoule,[44] but not all have practiced the injection, and most will depend on medical professionals to give it to them in the event of an adrenal crisis episode.[32] Patients may experience significant physical as well as cognitive impairment during their illness, which may impair their capacity to make wise decisions or administer medicine.[45] Therefore, patients should receive training on intramuscular hydrocortisone use and education on how to recognize an adrenal crisis, as well as assistance from a close family member or friend.[41]

In case an individual suffering from adrenal insufficiency loses consciousness, they must receive the necessary medical attention. Reminding patients to always wear or keep a MedicAlert bracelet or just an emergency card is important.[46] A survey of 46 patients revealed that some medical professionals are reluctant to medicate the condition even when it is brought to their attention, which is a serious cause for concern. Only 54% of patients got glucocorticoid administration within 30 minutes of arrival, even though 86% of patients were promptly attended to by a medical professional within forty-five minutes of a distress call.[47] In situations when doctors are unsure about a patient's need for additional hydrocortisone, it is wise to listen to patients and their loved ones as they frequently have the most knowledge about this rare disorder.[48]

Treatment

The two foundations of treatment for adrenal crisis are steroid replacement and fluid resuscitation.[5] When adrenal crisis treatment is started as soon as possible, it can be effective in preventing irreversible effects from prolonged hypotension.[9] Treatment shouldn't be postponed while doing diagnostic tests. If there is reason to suspect something, a blood sample could be taken right away for ACTH and serum cortisol testing; however, treatment needs to begin right away, regardless of the results of the assay. Once a patient has recovered clinically, it is safe to confirm the diagnosis in an acutely ill patient.[49]

In cases of emergency, parenteral hydrocortisone can be given as soon as possible by intramuscular (IM) injection while IV access is being established, or as a bolus injection of 100 mg of intravenous (IV) hydrocortisone. After this bolus, 200 mg of hydrocortisone should be administered every 24 hours, either continuously by IV infusion or, if that is not possible, in doses of 50 mg of hydrocortisone per IV/IM injection every 6 hours.[50] A constant infusion of hydrocortisone results in a cortisol concentration insert at a steady state.[51]

Hypovolemia and hyponatremia can be corrected with intravenous fluid resuscitation using isotonic sodium chloride 0.9%; the hypoglycemia may also need to be corrected with intravenous dextrose. Over the course of the first hour, a liter of saline 0.9% must be administered. Subsequent replacement fluids should be determined by measuring the serum electrolytes and conducting frequent hemodynamic monitoring.[52] In cases of secondary adrenal insufficiency, cortisol replacement can cause water diuresis along with suppress antidiuretic hormone. When combined with sodium replacement, these effects can quickly correct hyponatremia as well as osmotic demyelination syndrome. As a result, care must be taken to adjust sodium by less than 10 mEq during the first 24 hours.[53]

It is widely acknowledged that extra mineralocorticoid treatment is not necessary at hydrocortisone dosages greater than 50 mg/day because there is adequate action within the mineralocorticoid receptor.[8] In those who have primary adrenal insufficiency, fludrocortisone needs to be started with subsequent dose tapering; for most patients, a daily dose of 50–200 mcg is adequate.[52] According to current treatment guidelines of primary adrenal insufficiency, the doses of prednisolone and dexamethasone are recommended based on their glucocorticoid potency in relation to hydrocortisone.[50]

Patients with lymphocytic hypophysitis are most frequently those who experience both adrenal insufficiency as well as diabetes insipidus in rare instances. Whether or not a patient is receiving treatment for diabetes insipidus, fluid administration should be done carefully because too much fluid can lead to hypernatremia and too little water can cause hyponatremia. Hyponatremia is typically maintained with careful synchronization of urine output and a normal saline infusion.[7]

Outlook

Patients with hypoadrenalism are more likely to die from adrenal crises; the death rate from adrenal crises can amount to 6% of crisis events.[6] "Adrenal failure" accounted for 15% of deaths in a study conducted in Norway involving 130 Addison's disease patients, making it the second most common cause of death.[54] While symptoms may have gone unnoticed prior to the fatal episode, fatal adrenal crises have happened in patients who had never been diagnosed with hypoadrenalism.[55]

Epidemiology

An adrenal crisis occurs in roughly 6–8% of those with adrenal insufficiency annually.[7] Patients with primary hypoadrenalism experience adrenal crises somewhat more frequently compared to those with secondary adrenal insufficiency.[31] This is likely due to the fact that patients with primary hypoadrenalism lack mineralocorticoid secretion and some secondary adrenal insufficiency patients retain some cortisol secretion.[56] Despite varying degrees of consequent adrenal suppression, patients with hypoadrenalism from long-term glucocorticoid therapy rarely experience adrenal crises.[57]

Special populations

Geriatrics

All age groups are susceptible to misclassification of an adrenal crisis diagnosis,[7] but older patients may be more vulnerable if relative hypotension is not evaluated, given the age-related rise in blood pressure.[58] It is possible to confuse hyponatremia—a common sign of adrenal insufficiency or adrenal crisis—with the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, which is frequently brought on by disease, drugs, or aging itself.[59]

The treatment of pituitary tumors and the widespread use of opioids for both malignant and increasingly non-malignant pain, as well as exogenous glucocorticoid therapy for the numerous inflammatory as well as malignant conditions that become more common in people over 60, are the main causes of a new diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in older adults.[60][57] Adrenal crisis is more likely to occur in older people.[61] Urinary tract infections, particularly in older women, are often linked to an adrenal crisis, as is pneumonia as well as a flare-up of chronic respiratory disease.[62] Cellulitis is linked to adrenal crises within this age range and may be more prevalent in patients with fragile skin who have been exposed to higher doses of glucocorticoids.[63] Older adults frequently experience falls and fractures, which may be linked to postural hypotension, especially in those who have primary adrenal insufficiency.[64]

Older patients have a higher mortality rate from adrenal crisis, at least in part due to the existence of comorbidities that make treatment more difficult.[65]

While studies on the prevalence of adrenal crisis in older adults are scarce, one population-based investigation into hospital admissions for adrenal crisis found that the incidence increased with age in older patients, going from 24·3 (60–69 years) to 35·2 (70–79 years) and 45·8 (80+ years) per million per year. This is significantly higher compared to the general adult admission rate, which is 15·0 per million annually in the same population.[63]

Pregnancy

Most cases of adrenal insufficiency in pregnancy are identified before conception. Because the symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum (fatigue, vomiting, nausea, and mild hypotension) and normal pregnancy (nausea and vomiting) overlap, there is usually little clinical indication of adrenal insufficiency during pregnancy.[66] Adrenal insufficiency during pregnancy has only been documented in 100 cases as of 2018.[67]

Untreated adrenal crisis can cause severe morbidity in both the mother and the fetus, such as inadequate wound healing, infection, venous thromboembolism, extended hospital stays, preterm birth, fetal intrauterine growth restriction, and an increased risk of cesarean delivery.[68] The occurrence of adrenal crisis during pregnancy is uncommon, even in patients who have a documented history of adrenal insufficiency. In one study, pregnancy was identified as a trigger for adrenal crisis in 0.2% of the 423 patients. In a different study only 1.1% of the 93 patients in the study who had a known insufficiency experienced an adrenal crisis during pregnancy.[69]

Children

A common finding in children experiencing an adrenal crisis is hypoglycemia. This could be linked to seizures, which are extremely dangerous and can result in permanent brain damage or even death.[70] Due to issues with adrenomedullary development as well as epinephrine production, hypoglycemia, and hemodynamic disturbance may be more prominent in the context of acute adrenal insufficiency in congenital conditions, including congenital adrenal hyperplasia, compared to other forms of primary adrenal insufficiency.[71] The severity of the enzyme impairment is correlated with the degree of adrenomedullary dysfunction.[72] Severe hyperkalemia has also been linked to potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias.[73] Because the renal tubules' function is still developing in infants and early children with primary adrenal insufficiency, hyponatremia is of particular concern.[71]

Studies have demonstrated that younger children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia experience adrenal crisis events more frequently than older children and adolescents.[74] Furthermore, research on congenital adrenal hyperplasia in children shows that individuals with more severe salt-wasting types have a higher chance of needing to be hospitalized.[75] There are differences in the incidence of adrenal crises between the sexes, and these differences change with age.[76] Psychosocial factors have the potential to alter the baseline adrenal crisis risk as well, especially as patients transition from parental treatment oversight to self-management in adolescence.[77] Management in this age group is further complicated by changes in cortisol pharmacokinetics, resulting in an increased clearance as well as volume without a change to the cortisol half-life that has been shown during the pubertal period.[78]

There is still a significant morbidity and death associated with adrenal insufficiency in newborns and early children. It has been estimated that 5–10 episodes of adrenal crisis occur for every 100 patient years in children with adrenal insufficiency; incidences may be higher in specific countries. Adrenal crisis among kids results in death in about 1/200 cases.[13]

See also

- Stress dose

- Adrenal insufficiency

References

- ↑ "Monarch Initiative". https://monarchinitiative.org/MONDO:0019801.

- ↑ "ADRENAL". December 6, 2023. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/pronunciation/english/adrenal.

- ↑ "CRISIS". November 9, 2022. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/pronunciation/english/crisis.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Elshimy, Ghada; Chippa, Venu; Kaur, Jasleen; Jeong, Jordan M. (September 13, 2023). "Adrenal Crisis". StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499968/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 "Adrenal Crisis: Still a Deadly Event in the 21st Century". The American Journal of Medicine (Elsevier BV) 129 (3): 339.e1–339.e9. March 2016. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.021. PMID 26363354.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 "High incidence of adrenal crisis in educated patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency: a prospective study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 100 (2): 407–416. February 2015. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3191. PMID 25419882.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Adrenal crises: perspectives and research directions". Endocrine (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 55 (2): 336–345. February 2017. doi:10.1007/s12020-016-1204-2. PMID 27995500. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1791&context=med_article.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Acute adrenal insufficiency". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America (Elsevier BV) 35 (4): 767–75, ix. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2006.09.004. PMID 17127145.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 "Adrenal Crisis". The New England Journal of Medicine 381 (9): 852–861. August 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807486. PMID 31461595.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 "Risk factors for adrenal crisis in patients with adrenal insufficiency". Endocrine Journal (Japan Endocrine Society) 50 (6): 745–752. December 2003. doi:10.1507/endocrj.50.745. PMID 14709847.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Adrenal insufficiency". The New England Journal of Medicine (Massachusetts Medical Society) 335 (16): 1206–1212. October 1996. doi:10.1056/nejm199610173351607. PMID 8815944.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 "Corticotropin tests for hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal insufficiency: a metaanalysis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 93 (11): 4245–4253. November 2008. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0710. PMID 18697868.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Allolio, Bruno (2015). "EXTENSIVE EXPERTISE IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Adrenal crisis". European Journal of Endocrinology (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 172 (3): R115–R124. doi:10.1530/eje-14-0824. ISSN 0804-4643. PMID 25288693.

- ↑ "Addison patients in the Netherlands: medical report of the survey". The Hague: Dutch Addison Society. 1994.

- ↑ "Reduced lymphocyte beta 2-adrenoceptor density and impaired diastolic left ventricular function in patients with glucocorticoid deficiency". Clinical Endocrinology 40 (6): 769–775. June 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02511.x. PMID 8033368.

- ↑ "Why glucocorticoid withdrawal may sometimes be as dangerous as the treatment itself". European Journal of Internal Medicine (Elsevier BV) 24 (8): 714–720. December 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.05.014. PMID 23806261.

- ↑ "A Case of Severe Hyponatremia in a Patient With Primary Adrenal Insufficiency". Cureus (Cureus, Inc.) 13 (9): e17946. September 2021. doi:10.7759/cureus.17946. PMID 34660134.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 "Adrenal insufficiency". Lancet (Elsevier BV) 361 (9372): 1881–1893. May 2003. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13492-7. PMID 12788587.

- ↑ "Prednisolone metasulphobenzoate foam retention enemas suppress the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics (Wiley) 8 (2): 255–258. April 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00284.x. PMID 8038357.

- ↑ "Secondary adrenal insufficiency after glucocorticosteroid administration in acute spinal cord injury: a case report". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine (Informa UK Limited) 37 (6): 786–790. November 2014. doi:10.1179/2045772314y.0000000223. PMID 24969098.

- ↑ "Cushing's syndrome and adrenal insufficiency after intradermal triamcinolone acetonide for keloid scars". European Journal of Pediatrics (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 169 (9): 1147–1149. September 2010. doi:10.1007/s00431-010-1165-z. PMID 20186428.

- ↑ "Intra-articular glucocorticoid injections and their effect on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis function". Endocrine (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 48 (2): 410–416. March 2015. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0409-5. PMID 25182149.

- ↑ "Intra-articular methylprednisolone acetate injection at the knee joint and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: a randomized controlled study". Clinical Rheumatology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 33 (1): 99–103. January 2014. doi:10.1007/s10067-013-2374-4. PMID 23982564.

- ↑ "Lost in the mist: acute adrenal crisis following intranasal fluticasone propionate overuse". Case Reports in Medicine (Hindawi Limited) 2010: 1–4. 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/846534. PMID 20862350.

- ↑ "Adrenal suppression in patients taking inhaled glucocorticoids is highly prevalent and management can be guided by morning cortisol". European Journal of Endocrinology (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 173 (5): 633–642. November 2015. doi:10.1530/eje-15-0608. PMID 26294794.

- ↑ "Topical corticosteroid-induced adrenocortical insufficiency: clinical implications". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 3 (3): 141–147. 2002. doi:10.2165/00128071-200203030-00001. PMID 11978135.

- ↑ "Exogenous Cushing's syndrome and glucocorticoid withdrawal". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America (Elsevier BV) 34 (2): 371–84, ix. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2005.01.013. PMID 15850848.

- ↑ "Role of fluconazole in a case of rapid onset ritonavir and inhaled fluticasone-associated secondary adrenal insufficiency". International Journal of STD & AIDS 23 (5): 371–372. May 2012. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2009.009339. PMID 22648897.

- ↑ "Cushing's syndrome due to interaction between inhaled corticosteroids and itraconazole". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy (SAGE Publications) 38 (1): 46–49. January 2004. doi:10.1345/aph.1d222. PMID 14742792.

- ↑ "Adrenal Insufficiency in Corticosteroids Use: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 100 (6): 2171–2180. June 2015. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1218. PMID 25844620.

- ↑ Jump up to: 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Epidemiology of adrenal crisis in chronic adrenal insufficiency: the need for new prevention strategies". European Journal of Endocrinology (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 162 (3): 597–602. March 2010. doi:10.1530/eje-09-0884. PMID 19955259.

- ↑ Jump up to: 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 "Adrenal crisis in treated Addison's disease: a predictable but under-managed event". European Journal of Endocrinology (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 162 (1): 115–120. January 2010. doi:10.1530/eje-09-0559. PMID 19776201.

- ↑ "Addisonian crisis precipitated by thyroxine therapy: a complication of type 2 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome". Southern Medical Journal (Southern Medical Association) 96 (8): 824–827. August 2003. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000056647.58668.cd. PMID 14515930.

- ↑ "Predisposing factors for adrenal insufficiency". The New England Journal of Medicine (Massachusetts Medical Society) 360 (22): 2328–2339. May 2009. doi:10.1056/nejmra0804635. PMID 19474430.

- ↑ "Addisonian Crisis Due to Antitubercular Therapy". Indian Journal of Pediatrics 82 (9): 860. September 2015. doi:10.1007/s12098-015-1742-2. PMID 25772943.

- ↑ "Chronopharmacology of glucocorticoids". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews (Elsevier BV) 151–152: 245–261. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2019.02.004. PMID 30797955.

- ↑ "Corticosteroids: Mechanisms of Action in Health and Disease". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America (Elsevier BV) 42 (1): 15–31, vii. February 2016. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.002. PMID 26611548.

- ↑ Jump up to: 38.0 38.1 "The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology (Elsevier BV) 335 (1): 2–13. March 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.005. PMID 20398732.

- ↑ "Impaired pressor sensitivity to noradrenaline in septic shock patients with and without impaired adrenal function reserve". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (Wiley) 46 (6): 589–597. December 1998. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00833.x. PMID 9862249.

- ↑ "Metabolic effects of the nocturnal rise in cortisol on carbohydrate metabolism in normal humans". The Journal of Clinical Investigation (American Society for Clinical Investigation) 92 (5): 2283–2290. November 1993. doi:10.1172/jci116832. PMID 8227343.

- ↑ Jump up to: 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Guidance for the prevention and emergency management of adult patients with adrenal insufficiency". Clinical Medicine (Royal College of Physicians) 20 (4): 371–378. July 2020. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2019-0324. PMID 32675141.

- ↑ "Plasma cortisol levels before and during "low-dose" hydrocortisone therapy and their relationship to hemodynamic improvement in patients with septic shock". Intensive Care Medicine (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 26 (12): 1747–1755. December 2000. doi:10.1007/s001340000685. PMID 11271081.

- ↑ "Stress doses of glucocorticoids cannot prevent progression of all adrenal crises". Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology (Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology) 18 (1): 23–27. 2009. doi:10.1297/cpe.18.23. PMID 24790376.

- ↑ "A glucocorticoid education group meeting: an effective strategy for improving self-management to prevent adrenal crisis". European Journal of Endocrinology (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 169 (1): 17–22. July 2013. doi:10.1530/eje-12-1094. PMID 23636446.

- ↑ "Quality of self-care in patients on replacement therapy with hydrocortisone". Journal of Internal Medicine (Wiley) 246 (5): 497–501. November 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00538.x. PMID 10583719.

- ↑ "Corticosteroid therapy and intercurrent illness: the need for continuing patient education". Postgraduate Medical Journal (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 69 (810): 282–284. April 1993. doi:10.1136/pgmj.69.810.282. PMID 8321791.

- ↑ "Timelines in the management of adrenal crisis — targets, limits and reality". Clinical Endocrinology 82 (4): 497–502. April 2015. doi:10.1111/cen.12609. PMID 25200922.

- ↑ "How to avoid precipitating an acute adrenal crisis". BMJ 345 (oct09 3): e6333. October 2012. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6333. PMID 23048013.

- ↑ "Adrenal crisis: prevention and management in adult patients". Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism 10: 2042018819848218. 2019. doi:10.1177/2042018819848218. PMID 31223468.

- ↑ Jump up to: 50.0 50.1 "Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 101 (2): 364–389. February 2016. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1710. PMID 26760044.

- ↑ "Continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion therapy in Addison's disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 99 (11): 4149–4157. November 2014. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2433. PMID 25127090.

- ↑ Jump up to: 52.0 52.1 "Consensus statement on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with primary adrenal insufficiency". Journal of Internal Medicine 275 (2): 104–115. February 2014. doi:10.1111/joim.12162. PMID 24330030.

- ↑ "Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations". The American Journal of Medicine (Elsevier BV) 126 (10 Suppl 1): S1-42. October 2013. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.006. PMID 24074529.

- ↑ Bergthorsdottir, Ragnhildur; Leonsson-Zachrisson, Maria; Odén, Anders; Johannsson, Gudmundur (December 1, 2006). "Premature Mortality in Patients with Addison's Disease: A Population-Based Study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 91 (12): 4849–4853. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0076. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 16968806.

- ↑ Sævik, Å. B.; Åkerman, A.-K.; Grønning, K.; Nermoen, I.; Valland, S. F.; Finnes, T. E.; Isaksson, M.; Dahlqvist, P. et al. (November 3, 2017). "Clues for early detection of autoimmune Addison's disease – myths and realities". Journal of Internal Medicine (Wiley) 283 (2): 190–199. doi:10.1111/joim.12699. ISSN 0954-6820. PMID 29098731.

- ↑ Smans, Lisanne C.C.J.; Van der Valk, Eline S.; Hermus, Ad R.M.M.; Zelissen, Pierre M.J. (August 27, 2015). "Incidence of adrenal crisis in patients with adrenal insufficiency". Clinical Endocrinology (Wiley) 84 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1111/cen.12865. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 26208266.

- ↑ Jump up to: 57.0 57.1 Rushworth, R. Louise; Chrisp, Georgina L.; Torpy, David J. (2018). "Glucocorticoid-Induced Adrenal Insufficiency: A Study of the Incidence in Hospital Patients and A Review of Peri-Operative Management". Endocrine Practice (Elsevier BV) 24 (5): 437–445. doi:10.4158/ep-2017-0117. ISSN 1530-891X. PMID 29498915.

- ↑ Goubar, Thomas; Torpy, David J.; McGrath, Shaun; Rushworth, R. Louise (1 December 2019). "Prehospital Management of Acute Addison Disease: Audit of Patients Attending a Referral Hospital in a Regional Area". Journal of the Endocrine Society 3 (12): 2194–2203. doi:10.1210/js.2019-00263. ISSN 2472-1972. PMID 31723718.

- ↑ Falhammar, Henrik; Lindh, Jonatan D.; Calissendorff, Jan; Farmand, Shermineh; Skov, Jakob; Nathanson, David; Mannheimer, Buster (2018). "Differences in associations of antiepileptic drugs and hospitalization due to hyponatremia: A population–based case–control study". Seizure (Elsevier BV) 59: 28–33. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2018.04.025. ISSN 1059-1311. PMID 29730273.

- ↑ Regal, Milagros; Páramo, Concepción; Sierra, José M.; García-Mayor, Ricardo V. (2001). "Prevalence and incidence of hypopituitarism in an adult Caucasian population in northwestern Spain". Clinical Endocrinology 55 (6): 735–740. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01406.x. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 11895214. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01406.x. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ Iwasaku, Masahiro; Shinzawa, Maki; Tanaka, Shiro; Kimachi, Kimihiko; Kawakami, Koji (2017). "Clinical characteristics of adrenal crisis in adult population with and without predisposing chronic adrenal insufficiency: a retrospective cohort study". BMC Endocrine Disorders 17 (1): 58. doi:10.1186/s12902-017-0208-0. ISSN 1472-6823. PMID 28893233.

- ↑ Chen, Yi-Chun; Chen, Yu-Chun; Chou, Li-Fang; Chen, Tzeng-Ji; Hwang, Shinn-Jang (2010). "Adrenal Insufficiency in the Elderly: A Nationwide Study of Hospitalizations in Taiwan". The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine (Tohoku University Medical Press) 221 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1620/tjem.221.281. ISSN 0040-8727. PMID 20644343. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/tjem/221/4/221_4_281/_article/-char/ja/. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 63.0 63.1 Rushworth, R Louise; Torpy, David J (2014). "A descriptive study of adrenal crises in adults with adrenal insufficiency: increased risk with age and in those with bacterial infections". BMC Endocrine Disorders 14 (1): 79. doi:10.1186/1472-6823-14-79. ISSN 1472-6823. PMID 25273066.

- ↑ Falhammar, Henrik; Thorén, Marja (2012). "Clinical outcomes in the management of congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Endocrine 41 (3): 355–373. doi:10.1007/s12020-011-9591-x. ISSN 1355-008X. PMID 22228497. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12020-011-9591-x. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ Quinkler, Marcus; Ekman, Bertil; Zhang, Pinggao; Isidori, Andrea M.; Murray, Robert D.; on behalf of the EU-AIR Investigators (2018). "Mortality data from the European Adrenal Insufficiency Registry—Patient characterization and associations". Clinical Endocrinology 89 (1): 30–35. doi:10.1111/cen.13609. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 29682773.

- ↑ Manoharan, Madhavi; Sinha, Prabha; Sibtain, Shabnum (2020-08-17). "Adrenal disorders in pregnancy, labour and postpartum – an overview". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 40 (6): 749–758. doi:10.1080/01443615.2019.1648395. ISSN 0144-3615. PMID 31469031. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01443615.2019.1648395. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ Oliveira, Diana; Lages, Adriana; Paiva, Sandra; Carrilho, Francisco (April 12, 2018). "Treatment of Addison's disease during pregnancy". Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism Case Reports (Bioscientifica) 2018. doi:10.1530/edm-17-0179. ISSN 2052-0573. PMID 29675257.

- ↑ Langlois, Fabienne; Lim, Dawn S.T.; Fleseriu, Maria (2017). "Update on adrenal insufficiency: diagnosis and management in pregnancy". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity (Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health)) 24 (3): 184–192. doi:10.1097/med.0000000000000331. ISSN 1752-296X. PMID 28288009. https://journals.lww.com/co-endocrinology/abstract/2017/06000/update_on_adrenal_insufficiency__diagnosis_and.5.aspx. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ MacKinnon, Rene; Eubanks, Allison; Shay, Kelly; Belson, Brian (2021). "Diagnosing and managing adrenal crisis in pregnancy: A case report". Case Reports in Women's Health (Elsevier BV) 29: e00278. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2020.e00278. ISSN 2214-9112. PMID 33376678.

- ↑ DeVile, C. J.; Stanhope, R. (1997). "Hydrocortisone replacement therapy in children and adolescents with hypopituitarism". Clinical Endocrinology (Wiley) 47 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2101025.x. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 9302370.

- ↑ Jump up to: 71.0 71.1 Webb, Emma A.; Krone, Nils (2015). "Current and novel approaches to children and young people with congenital adrenal hyperplasia and adrenal insufficiency". Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (Elsevier BV) 29 (3): 449–468. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2015.04.002. ISSN 1521-690X. PMID 26051302. http://pure-oai.bham.ac.uk/ws/files/19590655/Webb_Krone_Current_novel_approaches_children_Best_Practice_Research_Clinical_Endocrinology_Metabolism_2015.pdf.

- ↑ Charmandari, Evangelia; Eisenhofer, Graeme; Mehlinger, Sarah L.; Carlson, Ann; Wesley, Robert; Keil, Margaret F.; Chrousos, George P.; New, Maria I. et al. (2002). "Adrenomedullary Function May Predict Phenotype and Genotype in Classic 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 87 (7): 3031–3037. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.7.8664. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 12107196.

- ↑ Parham, Walter A.; Mehdirad, Ali A.; Biermann, Kurt M.; Fredman, Carey S. (2006). "Hyperkalemia Revisited". Texas Heart Institute Journal (Texas Heart Institute) 33 (1): 40–47. PMID 16572868.

- ↑ Rushworth, R. Louise; Falhammar, Henrik; Munns, Craig F.; Maguire, Ann M.; Torpy, David J. (2016). "Hospital Admission Patterns in Children with CAH: Admission Rates and Adrenal Crises Decline with Age". International Journal of Endocrinology (Hindawi Limited) 2016: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2016/5748264. ISSN 1687-8337. PMID 26880914.

- ↑ Yang, Ming; White, Perrin C. (March 9, 2017). "Risk factors for hospitalization of children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Clinical Endocrinology (Wiley) 86 (5): 669–673. doi:10.1111/cen.13309. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 28192635.

- ↑ Rushworth, R. Louise; Chrisp, Georgina L.; Dean, Benjamin; Falhammar, Henrik; Torpy, David J. (2017). "Hospitalisation in Children with Adrenal Insufficiency and Hypopituitarism: Is There a Differential Burden between Boys and Girls and between Age Groups?". Hormone Research in Paediatrics (S. Karger AG) 88 (5): 339–346. doi:10.1159/000479370. ISSN 1663-2818. PMID 28898882.

- ↑ Lass, Nina; Reinehr, Thomas (2015). "Low Treatment Adherence in Pubertal Children Treated with Thyroxin or Growth Hormone". Hormone Research in Paediatrics (S. Karger AG) 84 (4): 240–247. doi:10.1159/000437305. ISSN 1663-2818. PMID 26279278.

- ↑ Charmandari, Evangelia; Hindmarsh, Peter C.; Johnston, Atholl; Brook, Charles G. D. (June 1, 2001). "Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency: Alterations in Cortisol Pharmacokinetics at Puberty". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (The Endocrine Society) 86 (6): 2701–2708. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.6.7522. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 11397874.

Further reading

- Eyal, Ori; Levin, Yair; Oren, Asaf; Zung, Amnon; Rachmiel, Marianna; Landau, Zohar; Schachter-Davidov, Anita; Segev-Becker, Anat et al. (2019). "Adrenal crises in children with adrenal insufficiency: epidemiology and risk factors". European Journal of Pediatrics 178 (5): 731–738. doi:10.1007/s00431-019-03348-1. ISSN 0340-6199. PMID 30806790. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00431-019-03348-1.

- Gardella, Barbara; Gritti, Andrea; Scatigno, Annachiara Licia; Gallotti, Anna Maria Clelia; Perotti, Francesca; Dominoni, Mattia (September 14, 2022). "Adrenal crisis during pregnancy: Case report and obstetric perspective". Frontiers in Medicine (Frontiers Media SA) 9. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.891101. ISSN 2296-858X. PMID 36186806.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|