Medicine:Hemoglobin E

| Hemoglobin E disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Haemoglobin E |

| |

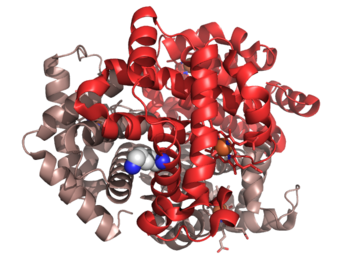

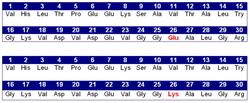

| Crystal structure of Hemoglobin E mutant (Glu26Lys) PDB entry 1vyt. Alpha chain in pink, beta chain in red. The lysine mutation highlighted as white spheres. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

Hemoglobin E (HbE) is an abnormal hemoglobin with a single point mutation in the β chain. At position 26 there is a change in the amino acid, from glutamic acid to lysine (E26K). Hemoglobin E is very common among people of Southeast Asian, Northeast Indian, Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi descent.[1][2]

The βE mutation affects β-gene expression creating an alternate splicing site in the mRNA at codons 25-27 of the β-globin gene. Through this mechanism, there is a mild deficiency in normal β mRNA and production of small amounts of anomalous β mRNA. The reduced synthesis of β chain may cause β-thalassemia. Also, this hemoglobin variant has a weak union between α- and β-globin, causing instability when there is a high amount of oxidant.[3] HbE can be detected on electrophoresis.

Hemoglobin E disease (EE)

Hemoglobin E disease results when the offspring inherits the gene for HbE from both parents. At birth, babies homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele do not present symptoms because they still have HbF (fetal hemoglobin). In the first months of life, fetal hemoglobin disappears and the amount of hemoglobin E increases, so the subjects start to have a mild β-thalassemia. Subjects homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele (two abnormal alleles) have a mild hemolytic anemia and mild enlargement of the spleen.

Hemoglobin E trait: heterozygotes for HbE (AE)

Heterozygous AE occurs when the gene for hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin A from the other. This is called hemoglobin E trait, and it is not a disease. People who have hemoglobin E trait (heterozygous) are asymptomatic and their state does not usually result in health problems. They may have a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and very abnormal red blood cells (target cells), but clinical relevance is mainly due to the potential for transmitting E or β-thalassemia.[4]

Sickle-Hemoglobin E Disease (SE)

Compound heterozygotes with sickle-hemoglobin E disease result when the gene of hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin S from the other. As the amount of fetal hemoglobin decreases and hemoglobin S increases, a mild hemolytic anemia appears in the early stage of development. Patients with this disease experience some of the symptoms of sickle cell anemia, including mild-moderate anemia, increased risk of infection, and painful sickling crises.[5]

Hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia

People who have hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia have inherited one gene for hemoglobin E from one parent and one gene for β-thalassemia from the other parent; affecting more than a million people in the world.[6] Symptoms of hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia vary widely in severity, from mild anemia to full thalassemia major; they can include growth retardation, enlargement of the spleen (splenomegaly) and liver (hepatomegaly), jaundice, bone abnormalities, and cardiovascular problems.[7] Recommended course of treatment depends on the nature and severity of the symptoms and may involve close monitoring of hemoglobin levels, folic acid supplements, and potentially regular blood transfusions.[7]

Epidemiology

Hemoglobin E is most prevalent in mainland Southeast Asia (Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam[8]), Sri Lanka, Northeast India and Bangladesh. In mainland Southeast Asia, its prevalence can reach 30 or 40%, and Northeast India, in certain areas it has carrier rates that reach 60% of the population. In Thailand the mutation can reach 50 or 70%, and it is higher in the northeast of the country. In Sri Lanka, it can reach up to 40% and affects those of Sinhalese and Vedda descent.[9][10] It is also found at high frequencies in Bangladesh and Indonesia.[11][12] The trait can also appear in people of Turkish, Chinese and Filipino descent.[1] The mutation is estimated to have arisen within the last 5,000 years.[13] In Europe, there have been found cases of families with hemoglobin E, but in these cases, the mutation differs from the one found in South-East Asia. This means that there may be different origins of the βE mutation.[14][15]

Protection against malaria

A number of studies have shown that the HbE mutation provides a degree of protection against infection with malaria, in common with some other hemoglobinopathies. It is therefore probable that natural selection for the gene may explain why it is most prevalent in parts of the world where malaria has historically been endemic.[16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Hemoglobin e Trait - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?ContentTypeID=160&ContentID=12.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.mhcs.health.nsw.gov.au/publicationsandresources/pdf/publication-pdfs/diseases-and-conditions/9095/oth-9095-eng.pdf.

- ↑ "Studies on hemoglobin E. I. The clinical, hematologic, and genetic characteristics of the hemoglobin E syndromes.". J Lab Clin Med 47 (3): 455–489. 1956. PMID 13353880.

- ↑ Bachir, D; Galacteros, F (November 2004), Hemoglobin E disease., Orphanet Encyclopedia, https://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-HbE.pdf, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ↑ Arkansas Department of Health. "Sickle-Hemoglobin E Disease Fact Sheet". https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/sickle-hemoglobin_e_disease.pdf.

- ↑ Vichinsky E (2007). "Hemoglobin E Syndromes.". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2007: 79–83. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.79. PMID 18024613.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fucharoen, Suthat; Weatherall, David J. (2012-08-01). "The Hemoglobin E Thalassemias" (in en). Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2 (8). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011734. ISSN 2157-1422. PMID 22908199.

- ↑ Hemoglobin E Trait, University of Rochester Medical Center, http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/Encyclopedia/Content.aspx?ContentTypeID=160&ContentID=12, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ↑ Sarkar, Jayanta; Ghosh, G. C. (2003). Populations of the SAARC Countries: Bio-cultural Perspectives. Sterling Publishers Pvt.. ISBN 978-81-207-2562-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=ywY_dN6ad8gC.

- ↑ Roychoudhury, Arun K.; Nei, Masatoshi (1985). "Genetic Relationships between Indians and Their Neighboring Populations". Human Heredity (S. Karger AG) 35 (4): 201–206. doi:10.1159/000153545. ISSN 1423-0062.

- ↑ Kumar, Dhavendra (2012-09-15). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-2231-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=2grSBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Hb E/beta-thalassaemia: a common & clinically diverse disorder". Indian J. Med. Res. 134 (4): 522–31. 2011. PMID 22089616.

- ↑ Ohashi (2004). "Extended linkage disequilibrium surrounding the hemoglobin E variant due to malarial selection". Am J Hum Genet 74 (6): 1189–1208. doi:10.1086/421330. PMID 15114532. Free full text

- ↑ Kazazian HH, JR., Waber PG, Boehm CD, Lee JI, Antonarakis SE, Fairbanks VF. (1984). "Hemoglobin E in Europeans: Further Evidence for Multiple Origins of the βE-Globin Gene.". Am J Hum Genet 36 (1): 212–217. PMID 6198908. Free full text

- ↑ Bain, Barbara J (June 2006). Blood cells: a practical guide (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-4265-6.

- ↑ Ha, Jiwoo; Martinson, Ryan; Iwamoto, Sage K; Nishi, Akihiro (2019-01-01). "Hemoglobin E, malaria and natural selection". Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 2019 (1): 232–241. doi:10.1093/emph/eoz034. ISSN 2050-6201. PMID 31890210. PMC 6925914. https://academic.oup.com/emph/article/2019/1/232/5675503.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Hemoglobin E fact sheet from the Washington State Department of Health

- American Society of Hematology Educational Program profile of Hemoglobin E disorders

- Orphanet Encyclopedia entry for Hemoglobin E

- Hemoglobin E in Europeans

|