Medicine:Trigeminal neuralgia

| Trigeminal neuralgia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tic douloureux,[1] prosopalgia,[2] Fothergill's disease,[3] suicide disease[4] |

| |

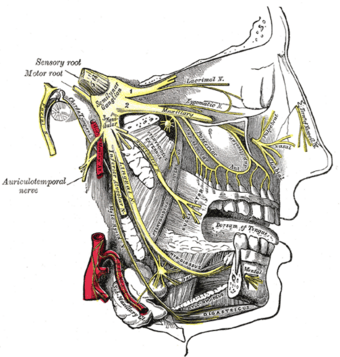

| The trigeminal nerve and its three major divisions (shown in yellow): the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3) | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Typical: episodes of severe, sudden, shock-like pain in one side of the face that lasts for seconds to minutes[1] Atypical: constant burning pain[1] |

| Complications | Depression[5] |

| Usual onset | > 50 years old[1] |

| Types | Typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia[1] |

| Causes | Believed to be due to problems with myelin of trigeminal nerve[1][6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Postherpetic neuralgia[1] |

| Treatment | Medication, surgery[1] |

| Medication | Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine[6] |

| Prognosis | 80% improve with initial treatment[6] |

| Frequency | 1 in 8,000 people per year[1] |

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN or TGN), also called Fothergill disease, tic douloureux, trifacial neuralgia, or suicide disease is a long-term pain disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve,[7][1] the nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing. It is a form of neuropathic pain.[8] There are two main types: typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia.[1] The typical form results in episodes of severe, sudden, shock-like pain in one side of the face that lasts for seconds to a few minutes.[1] Groups of these episodes can occur over a few hours.[1] The atypical form results in a constant burning pain that is less severe.[1] Episodes may be triggered by any touch to the face.[1] Both forms may occur in the same person.[1] It is regarded as one of the most painful disorders known to medicine, and often results in depression and suicide.[5]

The exact cause is unknown, but believed to involve loss of the myelin of the trigeminal nerve.[1][6] This might occur due to compression from a blood vessel as the nerve exits the brain stem, multiple sclerosis, stroke, or trauma.[1] Less common causes include a tumor or arteriovenous malformation.[1] It is a type of nerve pain.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on the symptoms, after ruling out other possible causes such as postherpetic neuralgia.[8][1]

Treatment includes medication or surgery.[1] The anticonvulsant carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine is usually the initial treatment, and is effective in about 90% of people.[8] Side effects are frequently experienced that necessitate drug withdrawal in as many as 23% of patients.[8] Other options include lamotrigine, baclofen, gabapentin, amitriptyline and pimozide.[6][1] Opioids are not usually effective in the typical form.[1] In those who do not improve or become resistant to other measures, a number of types of surgery may be tried.[6]

It is estimated that trigeminal neuralgia affects around 0.03% to 0.3% of people around the world with a female over-representation around a 3:1 ratio between women and men.[9] It usually begins in people over 50 years old, but can occur at any age.[1] The condition was first described in detail in 1773 by John Fothergill.[10]

Signs and symptoms

This disorder is characterized by episodes of severe facial pain along the trigeminal nerve divisions. The trigeminal nerve is a paired cranial nerve that has three major branches: the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3). One, two, or all three branches of the nerve may be affected. Trigeminal neuralgia most commonly involves the middle branch (the maxillary nerve or V2) and lower branch (mandibular nerve or V3) of the trigeminal nerve.[11]

An individual attack usually lasts from a few seconds to several minutes or hours, but these can repeat for hours with very short intervals between attacks. In other instances, only 4–10 attacks are experienced daily. The episodes of intense pain may occur paroxysmally. To describe the pain sensation, people often describe a trigger area on the face so sensitive that touching or even air currents can trigger an episode; however, in many people, the pain is generated spontaneously without any apparent stimulation. It affects lifestyle as it can be triggered by common activities such as eating, talking, shaving and brushing teeth. The wind, chewing, and talking can aggravate the condition in many patients. The attacks are said, by those affected, to feel like stabbing electric shocks, burning, sharp, pressing, crushing, exploding or shooting pain that becomes intractable.[8]

The pain also tends to occur in cycles with remissions lasting months or even years. Pain attacks are known to worsen in frequency or severity over time, in some people. Pain may migrate to other branches over time but in some people remains very stable.[12]

Bilateral (occurring on both sides) trigeminal neuralgia is very rare except for trigeminal neuralgia caused by multiple sclerosis (MS). This normally indicates problems with both trigeminal nerves, since one nerve serves the left side of the face and the other serves the right side. Occasional reports of bilateral trigeminal neuralgia reflect successive episodes of unilateral (only one side) pain switching the side of the face rather than pain occurring simultaneously on both sides.[13]

Rapid spreading of the pain, bilateral involvement or simultaneous participation with other major nerve trunks (such as Painful Tic Convulsif of nerves V & VII or occurrence of symptoms in the V and IX nerves) may suggest a systemic cause. Systemic causes could include multiple sclerosis or expanding cranial tumors.[14]

The severity of the pain makes it difficult to wash the face, shave, and perform good oral hygiene. The pain has a significant impact on activities of daily living especially as those affected live in fear of when they are going to get their next attack of pain and how severe it will be. It can lead to severe depression and anxiety.[15]

However, not all people will have the symptoms described above; there are variants of TN, one of which is atypical trigeminal neuralgia ("trigeminal neuralgia, type 2" or trigeminal neuralgia with concomitant pain),[16] based on a recent classification of facial pain.[17] In these instances there is also a more prolonged lower severity background pain that can be present for over 50% of the time and is described more as a burning or prickling, rather than a shock.

Trigeminal pain can also occur after an attack of herpes zoster. Post-herpetic neuralgia has the same manifestations as in other parts of the body. Herpes zoster oticus typically presents with inability to move many facial muscles, pain in the ear, taste loss on the front of the tongue, dry eyes and mouth, and a vesicular rash. Less than 1% of varicella zoster infections involve the facial nerve and result in this occurring.[18]

Trigeminal deafferentation pain (TDP), also termed anesthesia dolorosa, or colloquially as phantom face pain, is from unintentional damage to a trigeminal nerve following attempts to fix a nerve problem surgically. This pain is usually constant with a burning sensation and numbness. TDP is very difficult to treat as further surgeries are usually ineffective and possibly detrimental to the person.[19]

Causes

The trigeminal nerve is a mixed cranial nerve responsible for sensory data such as tactition (pressure), thermoception (temperature), and nociception (pain) originating from the face above the jawline; it is also responsible for the motor function of the muscles of mastication, the muscles involved in chewing but not facial expression.[20]

Several theories exist to explain the possible causes of this pain syndrome. It was once believed that the nerve was compressed in the opening from the inside to the outside of the skull; but leading research indicates that it is an enlarged or lengthened blood vessel – most commonly the superior cerebellar artery – compressing or throbbing against the microvasculature of the trigeminal nerve near its connection with the pons.[21] Such a compression can injure the nerve's protective myelin sheath and cause erratic and hyperactive functioning of the nerve. This can lead to pain attacks at the slightest stimulation of any area served by the nerve as well as hinder the nerve's ability to shut off the pain signals after the stimulation ends. This type of injury may rarely be caused by an aneurysm (an outpouching of a blood vessel); by an AVM (arteriovenous malformation);[22] by a tumor; such as an arachnoid cyst or meningioma in the cerebellopontine angle;[23] or by a traumatic event, such as a car accident.[24]

Short-term peripheral compression is often painless.[5] Persistent compression results in local demyelination with no loss of axon potential continuity. Chronic nerve entrapment results in demyelination primarily, with progressive axonal degeneration subsequently.[5] It is, "therefore widely accepted that trigeminal neuralgia is associated with demyelination of axons in the Gasserian ganglion, the dorsal root, or both."[25] It has been suggested that this compression may be related to an aberrant branch of the superior cerebellar artery that lies on the trigeminal nerve.[25] Further causes, besides an aneurysm, multiple sclerosis or cerebellopontine angle tumor, include: a posterior fossa tumor, any other expanding lesion or even brainstem diseases from strokes.[25]

Trigeminal neuralgia is found in 3–4% of people with multiple sclerosis, according to data from seven studies.[26][27] It has been theorized that this is due to damage to the spinal trigeminal complex.[28] Trigeminal pain has a similar presentation in patients with and without MS.[29]

Postherpetic neuralgia, which occurs after shingles, may cause similar symptoms if the trigeminal nerve is damaged, called Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2.

When there is no apparent structural cause, the syndrome is called idiopathic.

Diagnosis

Trigeminal neuralgia is diagnosed via the result of neurological and physical tests, as well as the individual's medical history.[1]

Management

As with many conditions without clear physical or laboratory diagnosis, TN is sometimes misdiagnosed. A person with TN will sometimes seek the help of numerous clinicians before a firm diagnosis is made.[citation needed]

There is evidence that points towards the need to quickly treat and diagnose TN. It is thought that the longer a patient has TN, the harder it may be to reverse the neural pathways associated with the pain.[citation needed]

The differential diagnosis includes temporomandibular disorder.[30] Since triggering may be caused by movements of the tongue or facial muscles, TN must be differentiated from masticatory pain that has the clinical characteristics of deep somatic rather than neuropathic pain. Masticatory pain will not be arrested by a conventional mandibular local anesthetic block.[14] One quick test a dentist might perform is a conventional inferior dental local anaesthetic block, if the pain is in this branch, as it will not arrest masticatory pain but will TN.[31]

Medical

- The anticonvulsant carbamazepine is the first line treatment; second line medications include baclofen, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, topiramate, gabapentin and pregabalin. Uncontrolled trials have suggested that clonazepam and lidocaine may be effective.[32]

- Antidepressant medications, such as amitriptyline have shown good efficacy in treating trigeminal neuralgia, especially if combined with an anti-convulsant drug such as pregabalin.[33]

- There is some evidence that duloxetine can also be used in some cases of neuropathic pain, especially in patients with major depressive disorder[34] as it is an antidepressant. However, it should, by no means, be considered a first line therapy and should only be tried by specialist advice.[35]

- There is controversy around opiate use such as morphine and oxycodone for treatment of TN, with varying evidence on its effectiveness for neuropathic pain. Generally, opioids are considered ineffective against TN and thus should not be prescribed.[36]

Surgical

Microvascular decompression provides freedom from pain in about 75% of patients presenting with drug-resistant trigeminal neuralgia.[37][38][39] While there may be pain relief after surgery, there is also a risk of adverse effects, such as facial numbness. Percutaneous radiofrequency thermorhizotomy may also be effective[40] as may stereotactic radiosurgery; however the effectiveness decreases with time.[41]

Surgical procedures can be separated into non-destructive and destructive:

Non-destructive

- Microvascular decompression – this involves a small incision behind the ear and some bone removal from the area. An incision through the meninges is made to expose the nerve. Any vascular compressions of the nerve are carefully moved and a sponge-like pad is placed between the compression and nerve, stopping unwanted pulsation and allowing myelin sheath healing.[citation needed]

Destructive

All destructive procedures will cause facial numbness, post relief, as well as pain relief.[38]

- Percutaneous techniques which all involve a needle or catheter entering the face up to the origin where the nerve splits into three divisions and then damaging this area, purposely, to produce numbness but also stop pain signals. These techniques are proven effective[40] especially in those where other interventions have failed or in those who are medically unfit for surgery such as the elderly.

- Balloon compression – inflation of a balloon at this point causing damage and stopping pain signals.

- Glycerol injection – deposition of a corrosive liquid called glycerol at this point causes damage to the nerve to hinder pain signals.

- Radiofrequency thermocoagulation rhizotomy – application of a heated needle to damage the nerve at this point.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery is a form of radiation therapy that focuses high-power energy on a small area of the body[42]

Support

Psychological and social support has found to play a key role in the management of chronic illnesses and chronic pain conditions, such as trigeminal neuralgia. Chronic pain can cause constant frustration to an individual as well as to those around them.[43]

History

Trigeminal neuralgia was first described by physician John Fothergill and treated surgically by John Murray Carnochan, both of whom were graduates of the University of Edinburgh Medical School. Historically TN has been called "suicide disease" due to studies by the pioneering forefather in neurosurgery Harvey Cushing involving 123 cases of TN during 1896 and 1912. In those studies it produced intense pain, higher rates of suicidal ideation in patients with severe migraines, and links to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders.[4][46][47]

Society and culture

Some individuals of note with TN include:

- Four-time British Prime Minister William Gladstone is believed to have had the disease.[48]

- Entrepreneur and author Melissa Seymour was diagnosed with TN in 2009 and underwent microvascular decompression surgery in a well documented case covered by magazines and newspapers which helped to raise public awareness of the illness in Australia . Seymour was subsequently made a Patron of the Trigeminal Neuralgia Association of Australia.[49]

- Salman Khan, an Indian film star, was diagnosed with TN in 2011. He underwent surgery in the US.[50]

- All-Ireland winning Gaelic footballer Christy Toye was diagnosed with the condition in 2013. He spent five months in his bedroom at home, returned for the 2014 season and lined out in another All-Ireland final with his team.[51]

- Jim Fitzpatrick – former Member of Parliament (MP) for Poplar and Limehouse – disclosed he had trigeminal neuralgia before undergoing neurosurgery. He has openly discussed his condition at parliamentary meetings and is a prominent figure in the TNA UK charity.[52]

- Jefferson Davis – President of the Confederate States of America[53]

- Charles Sanders Peirce – American philosopher, scientist and father of pragmatism.[54]

- Gloria Steinem – American feminist, journalist, and social and political activist[55]

- Anneli van Rooyen, Afrikaans singer-songwriter popular during the 1980s and 1990s, was diagnosed with atypical trigeminal neuralgia in 2004. During surgical therapy directed at alleviating the condition performed in 2007, Van Rooyen had permanent nerve damage, resulting in her near-complete retirement from performing.[56]

- H.R., singer of hardcore punk band Bad Brains[57]

- Aneeta Prem, British author, human rights campaigner, magistrate and the founder and president of Freedom Charity. Aneeta's experience of bilateral TN began in 2010, with severe pain and resulting sleep deprivation. Her condition remained undiagnosed until 2017. MVD Surgery to ameliorate the pain on the right-hand side was performed at UCHL in December 2019.[58]

- Travis Barker, drummer of rock band Blink-182[59]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 "Trigeminal Neuralgia Fact Sheet". National Institutes of Health. 17 March 2020. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Trigeminal-Neuralgia-Fact-Sheet.

- ↑ A text-book of practical medicine. D. Appleton & Co. 1869. p. 292. https://archive.org/details/atextbookpracti00hackgoog. Retrieved 2011-08-01. "prosopalgia."

- ↑ "Diagnosis and treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia". Journal of the American Dental Association 135 (12): 1713–1717. December 2004. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0124. PMID 15646605. http://jada.ada.org/cgi/content/full/135/12/1713. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Harvey Cushing's case series of trigeminal neuralgia at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a surgeon's quest to advance the treatment of the 'suicide disease'". Acta Neurochirurgica 153 (5): 1043–1050. May 2011. doi:10.1007/s00701-011-0975-8. PMID 21409517.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Lindsay Harmon, ed (2005). "6". Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 114. ISBN 0-86715-439-X. http://www.quintpub.com/display_detail.php3?psku=B439X.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Treatment options in trigeminal neuralgia". Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders 3 (2): 107–115. March 2010. doi:10.1177/1756285609359317. PMID 21179603.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia". National Organization for Rare Disorders, Inc.. 26 February 2014. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/trigeminal-neuralgia/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Trigeminal Neuralgia". The New England Journal of Medicine 383 (8): 754–762. August 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1914484. PMID 32813951.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia: Basic and Clinical Aspects". Current Neuropharmacology 18 (2): 109–119. 2020-01-23. doi:10.2174/1570159X17666191010094350. PMID 31608834.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia: historical notes and current concepts". The Neurologist 15 (2): 87–94. March 2009. doi:10.1097/nrl.0b013e3181775ac3. PMID 19276786.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia and Hemifacial Spasm". UF Health Shands Hospital. November 2012. http://com-neurosurgery-a2.sites.medinfo.ufl.edu/files/2012/11/trigeminal_neuralgia_brochure_for_web.pdf.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia: an overview". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 48 (5): 393–399. November 1979. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(79)90064-1. PMID 226915.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia: New classification and diagnostic grading for practice and research". Neurology 87 (2): 220–228. July 2016. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002840. PMID 27306631.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lindsay Harmon, ed (2005). "17". Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 453. ISBN 0-86715-439-X. http://www.quintpub.com/display_detail.php3?psku=B439X.

- ↑ "The psychosocial and affective burden of posttraumatic neuropathy following injuries to the trigeminal nerve". Journal of Orofacial Pain 27 (4): 293–303. 2013. doi:10.11607/jop.1056. PMID 24171179.

- ↑ "Neurological surgery: facial pain". Oregon Health & Science University. http://www.ohsu.edu/facialpain/facial_pain-dx.shtml.

- ↑ "A new classification for facial pain". Neurosurgery 53 (5): 1164–7. November 2003. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000088806.11659.D8. PMID 14580284.

- ↑ "Postherpetic Neuralgia and Trigeminal Neuralgia". Pain Research and Treatment 2017: 1681765. 2017. doi:10.1155/2017/1681765. PMID 29359044.

- ↑ "Anesthesia Dolorosa". The Facial Pain Association. 14 April 2021. https://www.facepain.org/understanding-facial-pain/diagnosis/anesthesia-dolorosa/.

- ↑ "The Trigeminal Nerve (CN V)". TeachMeAnatomy. 15 August 2020. https://teachmeanatomy.info/head/cranial-nerves/trigeminal-nerve/.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia--pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment". British Journal of Anaesthesia 87 (1): 117–132. July 2001. doi:10.1093/bja/87.1.117. PMID 11460800.

- ↑ "Intrinsic arteriovenous malformation of the trigeminal nerve". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques 37 (5): 681–683. September 2010. doi:10.1017/S0317167100010891. PMID 21059518.

- ↑ "Arachnoid cyst of the cerebellopontine angle manifesting as contralateral trigeminal neuralgia: case report". Neurosurgery 28 (6): 886–887. June 1991. doi:10.1097/00006123-199106000-00018. PMID 2067614.

- ↑ Whiplash injuries : the cervical acceleration/deceleration syndrome (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 2002. p. 481. ISBN 9780781726818. https://books.google.com/books?id=De5LdqgeSf4C&q=trigeminal+neuralgia+injury&pg=PA481.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Lindsay Harmon, ed (2005). "6". Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 115. ISBN 0-86715-439-X. http://www.quintpub.com/display_detail.php3?psku=B439X.

- ↑ "Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis". Pain 154 (5): 632–642. May 2013. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.002. PMID 23318126.

- ↑ "Symptomatic cranial neuralgias in multiple sclerosis: clinical features and treatment". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 114 (2): 101–107. February 2012. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.10.044. PMID 22130044.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia and pain related to multiple sclerosis". Pain 143 (3): 186–191. June 2009. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.026. PMID 19171430.

- ↑ "A clinical comparison of trigeminal neuralgic pain in patients with and without underlying multiple sclerosis". Neurological Sciences 26 (S2): s150–s151. May 2005. doi:10.1007/s10072-005-0431-8. PMID 15926016.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia mistaken as temporomandibular disorder". Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 1 (1): 41–50. 2001. doi:10.1067/med.2001.116846. http://www.jebdp.com/article/S1532-3382%2801%2970082-6/abstract.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Nerve Block". 9 December 2020. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2040595-overview.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy of trigeminal neuralgia". The Clinical Journal of Pain 18 (1): 22–27. 2002. doi:10.1097/00002508-200201000-00004. PMID 11803299.

- ↑ "Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia using Amitriptyline and Pregablin combination Therapy". African Journal of Biomedical Research 15 (1): 201–203. September 2012. http://www.bioline.org.br/pdf?md12033.

- ↑ "Rapid Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia and Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder With Duloxetine". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 48 (8): 1090–1092. August 2014. doi:10.1177/1060028014532789. PMID 24788987.

- ↑ "Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007115. January 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3. PMID 24385423.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia". BMJ 348 (feb17 9): g474. February 2014. doi:10.1136/bmj.g474. PMID 24534115. http://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/752707?path=/bmj/348/7946/Clinical_Review.full.pdf.

- ↑ "Pain Outcomes Following Microvascular Decompression for Drug-Resistant Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Neurosurgery 86 (2): 182–190. February 2020. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyz075. PMID 30892607.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Neurosurgical interventions for the treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011 (9): CD007312. September 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007312.pub2. PMID 21901707.

- ↑ "MVD Bests Gamma Knife for Pain in Trigeminal Neuralgia". 5 October 2015. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/852161.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "[Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with thermorhizotomy]". Neuro-Chirurgie 55 (2): 203–210. April 2009. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2009.01.015. PMID 19303114.

- ↑ "Long-term outcomes of Gamma Knife radiosurgery for classic trigeminal neuralgia: implications of treatment and critical review of the literature. Clinical article". Journal of Neurosurgery 111 (2): 351–358. August 2009. doi:10.3171/2009.2.JNS08977. PMID 19326987.

- ↑ "Stereotactic radiosurgery – Cyber Knife". https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/007274.htm.

- ↑ "Dr". American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/chronic-pain.aspx.

- ↑ "Management of chronic facial pain". Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 2 (2): 67–76. May 2009. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1202593. PMID 22110799.

- ↑ "Facial Neuralgia Resources". Trigeminal Neuralgia Resources / Facial Neuralgia Resources. http://www.facial-neuralgia.org/default.htm.

- ↑ "Why Trigeminal Neuralgia is Considered the "Suicide Disease"". Arizona Pain Specialists LLC. 26 September 2021. https://arizonapain.com/trigeminal-neuralgia-suicide-disease/.

- ↑ "Trigeminal neuralgia: historical notes and current concepts". The Neurologist 15 (2): 87–94. March 2009. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181775ac3. PMID 19276786.

- ↑ "William Gladstone: New Studies and Perspectives. Edited by Roland Quinault, Roger Swift, and Ruth Clayton Windscheffel.Farnham: Ashgate, 2012. Pp. xviii+350. $134.95." (in en). The Journal of Modern History 86 (4): 904–905. December 2014. doi:10.1086/678722.

- ↑ "Melissa Seymour: My perfect life is over". Womansday.ninemsn.com.au. 2009-06-18. http://womansday.ninemsn.com.au/trueconfessions/truelifestories/827292/melissa-seymour-my-perfect-life-is-over.

- ↑ "Salman suffering from the suicide disease". Hindustan Times. 2011-08-24. http://www.hindustantimes.com/news-feed/archives/salman-suffering-from-the-suicide-disease/article1-737044.aspx.

- ↑ Foley, Alan (16 September 2014). "Serious illness meant Christy Toye didn't play in 2013 but now he's set for All-Ireland final: The Donegal player has experienced a remarkable revival". The Score. http://www.thescore.ie/christy-toye-donegal-1674498-Sep2014/.

- ↑ "MP urges greater awareness of trigeminal neuralgia". BBC. 2010-07-27. http://news.bbc.co.uk/democracylive/hi/house_of_commons/newsid_8856000/8856344.stm.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Jefferson Davis' Farewell". https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Jefferson_Davis_Farewell.htm.

- ↑ Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1993. pp. 39–40.

- ↑ "Gloria". Mother Jones. November–December 1995. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/1995/11/gloria.

- ↑ "Anneli van Rooyen's road to recovery". News24. 2011-08-26. http://www.channel24.co.za/News/Local/Anneli-van-Rooyens-road-to-recovery-20110826.

- ↑ Guardian Music (2017-02-03). "Hardcore legend HR of Bad Brains to undergo brain surgery". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/feb/03/hr-bad-brains-surgery.

- ↑ "The latest news from TNA UK". 2020-06-01. https://emailsystem.tna.org.uk/t/ViewEmail/t/602CF56A5B0333492540EF23F30FEDED.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Blink 182 Drummer Travis Barker Uses CBD to Treat Rare Condition: "I Love CBD"". February 5, 2019. https://www.vaporvanity.com/travis-barker-blink-182-cbd-treats-rare-condition/.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|