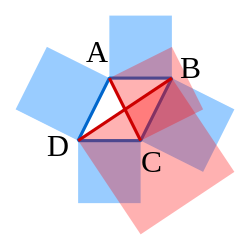

Parallelogram law

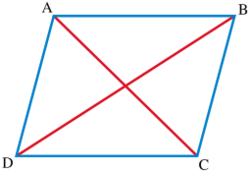

In mathematics, the simplest form of the parallelogram law (also called the parallelogram identity) belongs to elementary geometry. It states that the sum of the squares of the lengths of the four sides of a parallelogram equals the sum of the squares of the lengths of the two diagonals. We use these notations for the sides: AB, BC, CD, DA. But since in Euclidean geometry a parallelogram necessarily has opposite sides equal, that is, AB = CD and BC = DA, the law can be stated as

If the parallelogram is a rectangle, the two diagonals are of equal lengths AC = BD, so and the statement reduces to the Pythagorean theorem. For the general quadrilateral with four sides not necessarily equal, where is the length of the line segment joining the midpoints of the diagonals. It can be seen from the diagram that for a parallelogram, and so the general formula simplifies to the parallelogram law.

Proof

In the parallelogram on the right, let AD = BC = a, AB = DC = b, By using the law of cosines in triangle we get:

In a parallelogram, adjacent angles are supplementary, therefore Using the law of cosines in triangle produces:

By applying the trigonometric identity to the former result proves:

Now the sum of squares can be expressed as:

Simplifying this expression, it becomes:

The parallelogram law in inner product spaces

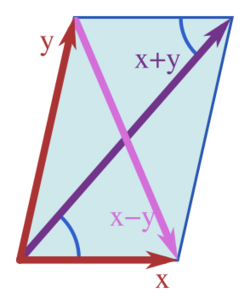

In a normed space, the statement of the parallelogram law is an equation relating norms:

The parallelogram law is equivalent to the seemingly weaker statement: because the reverse inequality can be obtained from it by substituting for and for and then simplifying. With the same proof, the parallelogram law is also equivalent to:

In an inner product space, the norm is determined using the inner product:

As a consequence of this definition, in an inner product space the parallelogram law is an algebraic identity, readily established using the properties of the inner product:

Adding these two expressions: as required.

If is orthogonal to meaning and the above equation for the norm of a sum becomes: which is Pythagoras' theorem.

Normed vector spaces satisfying the parallelogram law

Most real and complex normed vector spaces do not have inner products, but all normed vector spaces have norms (by definition). For example, a commonly used norm for a vector in the real coordinate space is the -norm:

Given a norm, one can evaluate both sides of the parallelogram law above. A remarkable fact is that if the parallelogram law holds, then the norm must arise in the usual way from some inner product. In particular, it holds for the -norm if and only if the so-called Euclidean norm or standard norm.[1][2]

For any norm satisfying the parallelogram law (which necessarily is an inner product norm), the inner product generating the norm is unique as a consequence of the polarization identity. In the real case, the polarization identity is given by: or equivalently by

In the complex case it is given by:

For example, using the -norm with and real vectors and the evaluation of the inner product proceeds as follows: which is the standard dot product of two vectors.

Another necessary and sufficient condition for there to exist an inner product that induces the given norm is for the norm to satisfy Ptolemy's inequality:[3]

See also

- Commutative property – Property of some mathematical operations

- François Daviet – Italian mathematician and military officer (1734–1798)

- Inner product space – Generalization of the dot product; used to define Hilbert spaces

- Minkowski distance – Vector distance using pth powers

- Normed vector space – Vector space on which a distance is defined

- Polarization identity – Formula relating the norm and the inner product in an inner product space

- Ptolemy's inequality

References

- ↑ Cantrell, Cyrus D. (2000). Modern mathematical methods for physicists and engineers. Cambridge University Press. p. 535. ISBN 0-521-59827-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=QKsiFdOvcwsC&pg=PA535. "if p ≠ 2, there is no inner product such that because the p-norm violates the parallelogram law."

- ↑ Saxe, Karen (2002). Beginning functional analysis. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 0-387-95224-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=0LeWJ74j8GQC&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1967). "Ptolemy's Inequality and the Chordal Metric" (in en). Mathematics Magazine 40 (5): 233–235. doi:10.2307/2688275. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0025570X.1967.11975804.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Parallelogram Law". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ParallelogramLaw.html.

- The Parallelogram Law Proven Simply at Dreamshire blog

- The Parallelogram Law: A Proof Without Words at cut-the-knot

|