Singular value decomposition

- Top: The action of M, indicated by its effect on the unit disc D and the two canonical unit vectors e1 and e2.

- Left: The action of V⁎, a rotation, on D, e1, and e2.

- Bottom: The action of Σ, a scaling by the singular values σ1 horizontally and σ2 vertically.

- Right: The action of U, another rotation.

In linear algebra, the singular value decomposition (SVD) is a factorization of a real or complex matrix into a rotation, followed by a rescaling followed by another rotation. It generalizes the eigendecomposition of a square normal matrix with an orthonormal eigenbasis to any matrix. It is related to the polar decomposition.

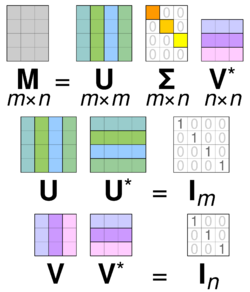

Specifically, the singular value decomposition of an complex matrix is a factorization of the form where is an complex unitary matrix, is an rectangular diagonal matrix with non-negative real numbers on the diagonal, is an complex unitary matrix, and is the conjugate transpose of . Such decomposition always exists for any complex matrix. If is real, then and can be guaranteed to be real orthogonal matrices; in such contexts, the SVD is often denoted

The diagonal entries of are uniquely determined by and are known as the singular values of . The number of non-zero singular values is equal to the rank of . The columns of and the columns of are called left-singular vectors and right-singular vectors of , respectively. They form two sets of orthonormal bases and and if they are sorted so that the singular values with value zero are all in the highest-numbered columns (or rows), the singular value decomposition can be written as where is the rank of

The SVD is not unique. However, it is always possible to choose the decomposition such that the singular values are in descending order. In this case, (but not and ) is uniquely determined by

The term sometimes refers to the compact SVD, a similar decomposition in which is square diagonal of size where is the rank of and has only the non-zero singular values. In this variant, is an semi-unitary matrix and is an semi-unitary matrix, such that

Mathematical applications of the SVD include computing the pseudoinverse, matrix approximation, and determining the rank, range, and null space of a matrix. The SVD is also extremely useful in many areas of science, engineering, and statistics, such as signal processing, least squares fitting of data, and process control.

Intuitive interpretations

Rotation, coordinate scaling, and reflection

In the special case when is an real square matrix, the matrices and can be chosen to be real matrices too. In that case, "unitary" is the same as "orthogonal". Then, interpreting both unitary matrices as well as the diagonal matrix, summarized here as as a linear transformation of the space the matrices and represent rotations or reflection of the space, while represents the scaling of each coordinate by the factor Thus the SVD decomposition breaks down any linear transformation of into a composition of three geometrical transformations: a rotation or reflection (), followed by a coordinate-by-coordinate scaling (), followed by another rotation or reflection ().

In particular, if has a positive determinant, then and can be chosen to be both rotations with reflections, or both rotations without reflections. If the determinant is negative, exactly one of them will have a reflection. If the determinant is zero, each can be independently chosen to be of either type.

If the matrix is real but not square, namely with it can be interpreted as a linear transformation from to Then and can be chosen to be rotations/reflections of and respectively; and besides scaling the first coordinates, also extends the vector with zeros, i.e. removes trailing coordinates, so as to turn into

Singular values as semiaxes of an ellipse or ellipsoid

As shown in the figure, the singular values can be interpreted as the magnitude of the semiaxes of an ellipse in 2D. This concept can be generalized to -dimensional Euclidean space, with the singular values of any square matrix being viewed as the magnitude of the semiaxis of an -dimensional ellipsoid. Similarly, the singular values of any matrix can be viewed as the magnitude of the semiaxis of an -dimensional ellipsoid in -dimensional space, for example as an ellipse in a (tilted) 2D plane in a 3D space. Singular values encode magnitude of the semiaxis, while singular vectors encode direction. See below for further details.

The columns of U and V are orthonormal bases

Since and are unitary, the columns of each of them form a set of orthonormal vectors, which can be regarded as basis vectors. The matrix maps the basis vector to the stretched unit vector By the definition of a unitary matrix, the same is true for their conjugate transposes and except the geometric interpretation of the singular values as stretches is lost. In short, the columns of and are orthonormal bases. When is a positive-semidefinite Hermitian matrix, and are both equal to the unitary matrix used to diagonalize However, when is not positive-semidefinite and Hermitian but still diagonalizable, its eigendecomposition and singular value decomposition are distinct.

Relation to the four fundamental subspaces

- The first columns of are a basis of the column space of .

- The last columns of are a basis of the null space of .

- The first columns of are a basis of the column space of (the row space of in the real case).

- The last columns of are a basis of the null space of .

Geometric meaning

Because and are unitary, we know that the columns of yield an orthonormal basis of and the columns of yield an orthonormal basis of (with respect to the standard scalar products on these spaces).

The linear transformation has a particularly simple description with respect to these orthonormal bases: we have where is the -th diagonal entry of and for

The geometric content of the SVD theorem can thus be summarized as follows: for every linear map one can find orthonormal bases of and such that maps the -th basis vector of to a non-negative multiple of the -th basis vector of and sends the leftover basis vectors to zero. With respect to these bases, the map is therefore represented by a diagonal matrix with non-negative real diagonal entries.

To get a more visual flavor of singular values and SVD factorization – at least when working on real vector spaces – consider the sphere of radius one in The linear map maps this sphere onto an ellipsoid in Non-zero singular values are simply the lengths of the semi-axes of this ellipsoid. Especially when and all the singular values are distinct and non-zero, the SVD of the linear map can be easily analyzed as a succession of three consecutive moves: consider the ellipsoid and specifically its axes; then consider the directions in sent by onto these axes. These directions happen to be mutually orthogonal. Apply first an isometry sending these directions to the coordinate axes of On a second move, apply an endomorphism diagonalized along the coordinate axes and stretching or shrinking in each direction, using the semi-axes lengths of as stretching coefficients. The composition then sends the unit-sphere onto an ellipsoid isometric to To define the third and last move, apply an isometry to this ellipsoid to obtain As can be easily checked, the composition coincides with

Example

Consider the matrix

A singular value decomposition of this matrix is given by

The scaling matrix is zero outside of the diagonal (grey italics) and one diagonal element is zero (red bold, light blue bold in dark mode). Furthermore, because the matrices and are unitary, multiplying by their respective conjugate transposes yields identity matrices, as shown below. In this case, because and are real valued, each is an orthogonal matrix.

This particular singular value decomposition is not unique. For instance, we can keep and the same, but change the last two rows of such that

and get an equally valid singular value decomposition. As the matrix has rank 3, it has only 3 nonzero singular values. In taking the product , the final column of and the final two rows of are multiplied by zero, so have no effect on the matrix product, and can be replaced by any unit vectors which are orthogonal to the first three and to each-other.

The compact SVD, , eliminates these superfluous rows, columns, and singular values:

SVD and spectral decomposition

Singular values, singular vectors, and their relation to the SVD

A non-negative real number is a singular value for if and only if there exist unit vectors in and in such that

The vectors and are called left-singular and right-singular vectors for respectively.

In any singular value decomposition the diagonal entries of are equal to the singular values of The first columns of and are, respectively, left- and right-singular vectors for the corresponding singular values. Consequently, the above theorem implies that:

- An matrix has at most distinct singular values.

- It is always possible to find a unitary basis for with a subset of basis vectors spanning the left-singular vectors of each singular value of

- It is always possible to find a unitary basis for with a subset of basis vectors spanning the right-singular vectors of each singular value of

A singular value for which we can find two left (or right) singular vectors that are linearly independent is called degenerate. If and are two left-singular vectors which both correspond to the singular value σ, then any normalized linear combination of the two vectors is also a left-singular vector corresponding to the singular value σ. The similar statement is true for right-singular vectors. The number of independent left and right-singular vectors coincides, and these singular vectors appear in the same columns of and corresponding to diagonal elements of all with the same value

As an exception, the left and right-singular vectors of singular value 0 comprise all unit vectors in the cokernel and kernel, respectively, of which by the rank–nullity theorem cannot be the same dimension if Even if all singular values are nonzero, if then the cokernel is nontrivial, in which case is padded with orthogonal vectors from the cokernel. Conversely, if then is padded by orthogonal vectors from the kernel. However, if the singular value of exists, the extra columns of or already appear as left or right-singular vectors.

Non-degenerate singular values always have unique left- and right-singular vectors, up to multiplication by a unit-phase factor (for the real case up to a sign). Consequently, if all singular values of a square matrix are non-degenerate and non-zero, then its singular value decomposition is unique, up to multiplication of a column of by a unit-phase factor and simultaneous multiplication of the corresponding column of by the same unit-phase factor. In general, the SVD is unique up to arbitrary unitary transformations applied uniformly to the column vectors of both and spanning the subspaces of each singular value, and up to arbitrary unitary transformations on vectors of and spanning the kernel and cokernel, respectively, of

Relation to eigenvalue decomposition

The singular value decomposition is very general in the sense that it can be applied to any matrix, whereas eigenvalue decomposition can only be applied to square diagonalizable matrices. Nevertheless, the two decompositions are related.

If has SVD the following two relations hold:

The right-hand sides of these relations describe the eigenvalue decompositions of the left-hand sides. Consequently:

- The columns of (referred to as right-singular vectors) are eigenvectors of

- The columns of (referred to as left-singular vectors) are eigenvectors of

- The non-zero elements of (non-zero singular values) are the square roots of the non-zero eigenvalues of or

In the special case of being a normal matrix, and thus also square, the spectral theorem ensures that it can be unitarily diagonalized using a basis of eigenvectors, and thus decomposed as for some unitary matrix and diagonal matrix with complex elements along the diagonal. When is positive semi-definite, will be non-negative real numbers so that the decomposition is also a singular value decomposition. Otherwise, it can be recast as an SVD by moving the phase of each to either its corresponding or The natural connection of the SVD to non-normal matrices is through the polar decomposition theorem: where is positive semidefinite and normal, and is unitary.

Thus, except for positive semi-definite matrices, the eigenvalue decomposition and SVD of while related, differ: the eigenvalue decomposition is where is not necessarily unitary and is not necessarily positive semi-definite, while the SVD is where is diagonal and positive semi-definite, and and are unitary matrices that are not necessarily related except through the matrix While only non-defective square matrices have an eigenvalue decomposition, any matrix has a SVD.

Applications of the SVD

Pseudoinverse

The singular value decomposition can be used for computing the pseudoinverse of a matrix. The pseudoinverse of the matrix with singular value decomposition is where is the pseudoinverse of , which is formed by replacing every non-zero diagonal entry by its reciprocal and transposing the resulting matrix. The pseudoinverse is one way to solve linear least squares problems.

Solving homogeneous linear equations

A set of homogeneous linear equations can be written as for a matrix , vector , and zero vector . A typical situation is that is known and a non-zero is to be determined which satisfies the equation. Such an belongs to 's null space and is sometimes called a (right) null vector of The vector can be characterized as a right-singular vector corresponding to a singular value of that is zero. This observation means that if is a square matrix and has no vanishing singular value, the equation has no non-zero as a solution. It also means that if there are several vanishing singular values, any linear combination of the corresponding right-singular vectors is a valid solution. Analogously to the definition of a (right) null vector, a non-zero satisfying with denoting the conjugate transpose of is called a left null vector of

Total least squares minimization

A total least squares problem seeks the vector that minimizes the 2-norm of a vector under the constraint The solution turns out to be the right-singular vector of corresponding to the smallest singular value.

Range, null space and rank

Another application of the SVD is that it provides an explicit representation of the range and null space of a matrix The right-singular vectors corresponding to vanishing singular values of span the null space of and the left-singular vectors corresponding to the non-zero singular values of span the range of For example, in the above example the null space is spanned by the last row of and the range is spanned by the first three columns of

As a consequence, the rank of equals the number of non-zero singular values which is the same as the number of non-zero diagonal elements in . In numerical linear algebra the singular values can be used to determine the effective rank of a matrix, as rounding error may lead to small but non-zero singular values in a rank deficient matrix. Singular values beyond a significant gap are assumed to be numerically equivalent to zero.

Low-rank matrix approximation

Some practical applications need to solve the problem of approximating a matrix with another matrix , said to be truncated, which has a specific rank . In the case that the approximation is based on minimizing the Frobenius norm of the difference between and under the constraint that it turns out that the solution is given by the SVD of namely where is the same matrix as except that it contains only the largest singular values (the other singular values are replaced by zero). This is known as the Eckart–Young theorem, as it was proved by those two authors in 1936.[lower-alpha 1]

Image compression

One practical consequence of the low-rank approximation given by SVD is that a greyscale image represented as an

matrix

, can be efficiently represented by keeping the first

singular values and corresponding vectors. The truncated decomposition

gives an image with the best 2-norm error out of all rank k approximations. Thus, the task becomes finding an approximation that balances retaining perceptual fidelity with the number of vectors required to reconstruct the image. Storing requires only floating-point numbers compared to integers. This same idea extends to color images by applying this operation to each channel or stacking the channels into one matrix.

Since the singular values of most natural images decay quickly, most of their variance is often captured by a small . For a 1528 × 1225 greyscale image, we can achieve a relative error of with as little as .[1] In practice, however, computing the SVD can be too computationally expensive and the resulting compression is typically less storage efficient than a specialized algorithm such as JPEG.

Separable models

The SVD can be thought of as decomposing a matrix into a weighted, ordered sum of separable matrices. By separable, we mean that a matrix can be written as an outer product of two vectors or, in coordinates, Specifically, the matrix can be decomposed as,

Here and are the -th columns of the corresponding SVD matrices, are the ordered singular values, and each is separable. The SVD can be used to find the decomposition of an image processing filter into separable horizontal and vertical filters. Note that the number of non-zero is exactly the rank of the matrix. Separable models often arise in biological systems, and the SVD factorization is useful to analyze such systems. For example, some visual area V1 simple cells' receptive fields can be well described[2] by a Gabor filter in the space domain multiplied by a modulation function in the time domain. Thus, given a linear filter evaluated through, for example, reverse correlation, one can rearrange the two spatial dimensions into one dimension, thus yielding a two-dimensional filter (space, time) which can be decomposed through SVD. The first column of in the SVD factorization is then a Gabor while the first column of represents the time modulation (or vice versa). One may then define an index of separability

which is the fraction of the power in the matrix M which is accounted for by the first separable matrix in the decomposition.[3]

Nearest orthogonal matrix

It is possible to use the SVD of a square matrix to determine the orthogonal matrix closest to The closeness of fit is measured by the Frobenius norm of The solution is the product [4][5] This intuitively makes sense because an orthogonal matrix would have the decomposition where is the identity matrix, so that if then the product amounts to replacing the singular values with ones. Equivalently, the solution is the unitary matrix of the Polar Decomposition in either order of stretch and rotation, as described above.

A similar problem, with interesting applications in shape analysis, is the orthogonal Procrustes problem, which consists of finding an orthogonal matrix which most closely maps to Specifically, where denotes the Frobenius norm.

This problem is equivalent to finding the nearest orthogonal matrix to a given matrix .

The Kabsch algorithm

The Kabsch algorithm (called Wahba's problem in other fields) uses SVD to compute the optimal rotation (with respect to least-squares minimization) that will align a set of points with a corresponding set of points. It is used, among other applications, to compare the structures of molecules.

Principal Component Analysis

The SVD can be used to construct the principal components in principal component analysis as follows:[6]

Let be a data matrix where each of the rows is a (feature-wise) mean-centered observation, each of dimension .

The SVD of is:

We see that contains the scores of the rows of (i.e. each observation), and is the matrix whose columns are principal component loading vectors.[6]

Signal processing

The SVD and pseudoinverse have been successfully applied to signal processing,[7] image processing[8] and big data (e.g., in genomic signal processing).[9][10][11][12]

Other examples

The SVD is also applied extensively to the study of linear inverse problems and is useful in the analysis of regularization methods such as that of Tikhonov. It is widely used in statistics, where it is related to principal component analysis and to correspondence analysis, and in signal processing and pattern recognition. It is also used in output-only modal analysis, where the non-scaled mode shapes can be determined from the singular vectors. Yet another usage is latent semantic indexing in natural-language text processing.

In general numerical computation involving linear or linearized systems, there is a universal constant that characterizes the regularity or singularity of a problem, which is the system's "condition number" . It often controls the error rate or convergence rate of a given computational scheme on such systems.[13][14]

The SVD also plays a crucial role in the field of quantum information, in a form often referred to as the Schmidt decomposition. Through it, states of two quantum systems are naturally decomposed, providing a necessary and sufficient condition for them to be entangled: if the rank of the matrix is larger than one.

One application of SVD to rather large matrices is in numerical weather prediction, where Lanczos methods are used to estimate the most linearly quickly growing few perturbations to the central numerical weather prediction over a given initial forward time period; i.e., the singular vectors corresponding to the largest singular values of the linearized propagator for the global weather over that time interval. The output singular vectors in this case are entire weather systems. These perturbations are then run through the full nonlinear model to generate an ensemble forecast, giving a handle on some of the uncertainty that should be allowed for around the current central prediction.

SVD has also been applied to reduced order modelling. The aim of reduced order modelling is to reduce the number of degrees of freedom in a complex system which is to be modeled. SVD was coupled with radial basis functions to interpolate solutions to three-dimensional unsteady flow problems.[15]

Interestingly, SVD has been used to improve gravitational waveform modeling by the ground-based gravitational-wave interferometer aLIGO.[16] SVD can help to increase the accuracy and speed of waveform generation to support gravitational-waves searches and update two different waveform models.

Singular value decomposition is used in recommender systems to predict people's item ratings.[17] Distributed algorithms have been developed for the purpose of calculating the SVD on clusters of commodity machines.[18]

Low-rank SVD has been applied for hotspot detection from spatiotemporal data with application to disease outbreak detection.[19] A combination of SVD and higher-order SVD also has been applied for real time event detection from complex data streams (multivariate data with space and time dimensions) in disease surveillance.[20]

In astrodynamics, the SVD and its variants are used as an option to determine suitable maneuver directions for transfer trajectory design[21] and orbital station-keeping.[22]

The SVD can be used to measure the similarity between real-valued matrices.[23] By measuring the angles between the singular vectors, the inherent two-dimensional structure of matrices is accounted for. This method was shown to outperform cosine similarity and Frobenius norm in most cases, including brain activity measurements from neuroscience experiments.

Proof of existence

An eigenvalue of a matrix is characterized by the algebraic relation When is Hermitian, a variational characterization is also available. Let be a real symmetric matrix. Define

By the extreme value theorem, this continuous function attains a maximum at some when restricted to the unit sphere By the Lagrange multipliers theorem, necessarily satisfies for some real number The nabla symbol, , is the del operator (differentiation with respect to ). Using the symmetry of we obtain

Therefore so is a unit length eigenvector of For every unit length eigenvector of its eigenvalue is so is the largest eigenvalue of The same calculation performed on the orthogonal complement of gives the next largest eigenvalue and so on. The complex Hermitian case is similar; there is a real-valued function of real variables.

Singular values are similar in that they can be described algebraically or from variational principles. Although, unlike the eigenvalue case, Hermiticity, or symmetry, of is no longer required.

This section gives these two arguments for existence of singular value decomposition.

Based on the spectral theorem

Let be an complex matrix. Since is positive semi-definite and Hermitian, by the spectral theorem, there exists an unitary matrix such that where is diagonal and positive definite, of dimension , with the number of non-zero eigenvalues of (which can be shown to verify ). Note that is here by definition a matrix whose -th column is the -th eigenvector of , corresponding to the eigenvalue . Moreover, the -th column of , for , is an eigenvector of with eigenvalue . This can be expressed by writing as , where the columns of and therefore contain the eigenvectors of corresponding to non-zero and zero eigenvalues, respectively. Using this rewriting of , the equation becomes:

This implies that

Moreover, the second equation implies .[lower-alpha 2] Finally, the unitary-ness of translates, in terms of and , into the following conditions: where the subscripts on the identity matrices are used to remark that they are of different dimensions.

Let us now define

Then,

since This can be also seen as immediate consequence of the fact that . This is equivalent to the observation that if is the set of eigenvectors of corresponding to non-vanishing eigenvalues , then is a set of orthogonal vectors, and is a (generally not complete) set of orthonormal vectors. This matches with the matrix formalism used above denoting with the matrix whose columns are , with the matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors of with vanishing eigenvalue, and the matrix whose columns are the vectors .

We see that this is almost the desired result, except that and are in general not unitary, since they might not be square. However, we do know that the number of rows of is no smaller than the number of columns, since the dimensions of is no greater than and . Also, since the columns in are orthonormal and can be extended to an orthonormal basis. This means that we can choose such that is unitary.

For we already have to make it unitary. Now, define

where extra zero rows are added or removed to make the number of zero rows equal the number of columns of and hence the overall dimensions of equal to . Then which is the desired result:

Notice the argument could begin with diagonalizing rather than (This shows directly that and have the same non-zero eigenvalues).

Based on variational characterization

The singular values can also be characterized as the maxima of considered as a function of and over particular subspaces. The singular vectors are the values of and where these maxima are attained.

Let denote an matrix with real entries. Let be the unit -sphere in , and define

Consider the function restricted to Since both and are compact sets, their product is also compact. Furthermore, since is continuous, it attains a largest value for at least one pair of vectors in and in This largest value is denoted and the corresponding vectors are denoted and Since is the largest value of it must be non-negative. If it were negative, changing the sign of either or would make it positive and therefore larger.

Statement — and are left and right-singular vectors of with corresponding singular value

Similar to the eigenvalues case, by assumption the two vectors satisfy the Lagrange multiplier equation:

After some algebra, this becomes

Multiplying the first equation from left by and the second equation from left by and taking into account gives

Plugging this into the pair of equations above, we have

This proves the statement.

More singular vectors and singular values can be found by maximizing over normalized and which are orthogonal to and respectively.

The passage from real to complex is similar to the eigenvalue case.

Calculating the SVD

One-sided Jacobi algorithm

One-sided Jacobi algorithm is an iterative algorithm,[24] where a matrix is iteratively transformed into a matrix with orthogonal columns. The elementary iteration is given as a Jacobi rotation, where the angle of the Jacobi rotation matrix is chosen such that after the rotation the columns with numbers and become orthogonal. The indices are swept cyclically, , where is the number of columns.

After the algorithm has converged, the singular value decomposition is recovered as follows: the matrix is the accumulation of Jacobi rotation matrices, the matrix is given by normalising the columns of the transformed matrix , and the singular values are given as the norms of the columns of the transformed matrix .

Two-sided Jacobi algorithm

Two-sided Jacobi SVD algorithm—a generalization of the Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm—is an iterative algorithm where a square matrix is iteratively transformed into a diagonal matrix. If the matrix is not square the QR decomposition is performed first and then the algorithm is applied to the matrix. The elementary iteration zeroes a pair of off-diagonal elements by first applying a Givens rotation to symmetrize the pair of elements and then applying a Jacobi transformation to zero them, where is the Givens rotation matrix with the angle chosen such that the given pair of off-diagonal elements become equal after the rotation, and where is the Jacobi transformation matrix that zeroes these off-diagonal elements. The iterations proceeds exactly as in the Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm: by cyclic sweeps over all off-diagonal elements.

After the algorithm has converged the resulting diagonal matrix contains the singular values. The matrices and are accumulated as follows:

Numerical approach

The singular value decomposition can be computed using the following observations:

- The left-singular vectors of are a set of orthonormal eigenvectors of .

- The right-singular vectors of are a set of orthonormal eigenvectors of .

- The non-zero singular values of (found on the diagonal entries of ) are the square roots of the non-zero eigenvalues of both and .

The SVD of a matrix is typically computed by a two-step procedure. In the first step, the matrix is reduced to a bidiagonal matrix. This takes order floating-point operations ( flop), assuming that The second step is to compute the SVD of the bidiagonal matrix. This step can only be done with an iterative method (as with eigenvalue algorithms). However, in practice it suffices to compute the SVD up to a certain precision, like the machine epsilon. If this precision is considered constant, then the second step takes iterations, each costing flops. Thus, the first step is more expensive, and the overall cost is flops.[25]

The first step can be done using Householder reflections for a cost of flops, assuming that only the singular values are needed and not the singular vectors. If is much larger than then it is advantageous to first reduce the matrix to a triangular matrix with the QR decomposition and then use Householder reflections to further reduce the matrix to bidiagonal form; the combined cost is flops.[25]

The second step can be done by a variant of the QR algorithm for the computation of eigenvalues, which was first described by Golub and Kahan in 1965.[26] The LAPACK subroutine DBDSQR[27] implements this iterative method, with some modifications to cover the case where the singular values are very small.[28] Together with a first step using Householder reflections and, if appropriate, QR decomposition, this forms the DGESVD routine[29] for the computation of the singular value decomposition.

The same algorithm is implemented in the GNU Scientific Library (GSL). The GSL also offers an alternative method that uses a one-sided Jacobi orthogonalization in step 2.[30] This method computes the SVD of the bidiagonal matrix by solving a sequence of SVD problems, similar to how the Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm solves a sequence of eigenvalue methods.[31] Yet another method for step 2 uses the idea of divide-and-conquer eigenvalue algorithms.[25]

There is an alternative way that does not explicitly use the eigenvalue decomposition.[32] Usually the singular value problem of a matrix is converted into an equivalent symmetric eigenvalue problem such as or

The approaches that use eigenvalue decompositions are based on the QR algorithm, which is well-developed to be stable and fast. Note that the singular values are real and right- and left- singular vectors are not required to form similarity transformations. One can iteratively alternate between the QR decomposition and the LQ decomposition to find the real diagonal Hermitian matrices. The QR decomposition gives and the LQ decomposition of gives Thus, at every iteration, we have update and repeat the orthogonalizations. Eventually,[clarification needed] this iteration between QR decomposition and LQ decomposition produces left- and right- unitary singular matrices. This approach cannot readily be accelerated, as the QR algorithm can with spectral shifts or deflation. This is because the shift method is not easily defined without using similarity transformations. However, this iterative approach is very simple to implement, so is a good choice when speed does not matter. This method also provides insight into how purely orthogonal/unitary transformations can obtain the SVD.

Analytic result of 2 × 2 SVD

The singular values of a matrix can be found analytically. Let the matrix be

where are complex numbers that parameterize the matrix, is the identity matrix, and denote the Pauli matrices. Then its two singular values are given by

Reduced SVDs

In applications it is quite unusual for the full SVD, including a full unitary decomposition of the null-space of the matrix, to be required. Instead, it is often sufficient (as well as faster, and more economical for storage) to compute a reduced version of the SVD. The following can be distinguished for an matrix of rank :

Thin SVD

The thin, or economy-sized, SVD of a matrix is given by[33]

where the matrices and contain only the first columns of and and contains only the first singular values from The matrix is thus is diagonal, and is

The thin SVD uses significantly less space and computation time if The first stage in its calculation will usually be a QR decomposition of which can make for a significantly quicker calculation in this case.

Compact SVD

The compact SVD of a matrix is given by

Only the column vectors of and row vectors of corresponding to the non-zero singular values are calculated. The remaining vectors of and are not calculated. This is quicker and more economical than the thin SVD if The matrix is thus is diagonal, and is

Truncated SVD

In many applications the number of the non-zero singular values is large making even the Compact SVD impractical to compute. In such cases, the smallest singular values may need to be truncated to compute only non-zero singular values. The truncated SVD is no longer an exact decomposition of the original matrix but rather provides the optimal low-rank matrix approximation by any matrix of a fixed rank

where matrix is is diagonal, and is Only the column vectors of and row vectors of corresponding to the largest singular values are calculated. This can be much quicker and more economical than the compact SVD if but requires a completely different toolset of numerical solvers.

In applications that require an approximation to the Moore–Penrose inverse of the matrix the smallest singular values of are of interest, which are more challenging to compute compared to the largest ones.

Truncated SVD is employed in latent semantic indexing.[34]

Norms

Ky Fan norms

The sum of the largest singular values of is a matrix norm, the Ky Fan -norm of [35]

The first of the Ky Fan norms, the Ky Fan 1-norm, is the same as the operator norm of as a linear operator with respect to the Euclidean norms of and In other words, the Ky Fan 1-norm is the operator norm induced by the standard Euclidean inner product. For this reason, it is also called the operator 2-norm. One can easily verify the relationship between the Ky Fan 1-norm and singular values. It is true in general, for a bounded operator on (possibly infinite-dimensional) Hilbert spaces

But, in the matrix case, is a normal matrix, so is the largest eigenvalue of i.e. the largest singular value of

The last of the Ky Fan norms, the sum of all singular values, is the trace norm (also known as the 'nuclear norm'), defined by (the eigenvalues of are the squares of the singular values).

Hilbert–Schmidt norm

The singular values are related to another norm on the space of operators. Consider the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product on the matrices, defined by

So the induced norm is

Since the trace is invariant under unitary equivalence, this shows

where are the singular values of This is called the Frobenius norm, Schatten 2-norm, or Hilbert–Schmidt norm of Direct calculation shows that the Frobenius norm of coincides with:

In addition, the Frobenius norm and the trace norm (the nuclear norm) are special cases of the Schatten norm.

Variations and generalizations

Scale-invariant SVD

The singular values of a matrix are uniquely defined and are invariant with respect to left and/or right unitary transformations of In other words, the singular values of for unitary matrices and are equal to the singular values of This is an important property for applications in which it is necessary to preserve Euclidean distances and invariance with respect to rotations.

The Scale-Invariant SVD, or SI-SVD,[36] is analogous to the conventional SVD except that its uniquely-determined singular values are invariant with respect to diagonal transformations of In other words, the singular values of for invertible diagonal matrices and are equal to the singular values of This is an important property for applications for which invariance to the choice of units on variables (e.g., metric versus imperial units) is needed.

Bounded operators on Hilbert spaces

The factorization can be extended to a bounded operator on a separable Hilbert space Namely, for any bounded operator there exist a partial isometry a unitary a measure space and a non-negative measurable such that

where is the multiplication by on

This can be shown by mimicking the linear algebraic argument for the matrix case above. is the unique positive square root of as given by the Borel functional calculus for self-adjoint operators. The reason why need not be unitary is that, unlike the finite-dimensional case, given an isometry with nontrivial kernel, a suitable may not be found such that

is a unitary operator.

As for matrices, the singular value factorization is equivalent to the polar decomposition for operators: we can simply write

and notice that is still a partial isometry while is positive.

Singular values and compact operators

The notion of singular values and left/right-singular vectors can be extended to compact operator on Hilbert space as they have a discrete spectrum. If is compact, every non-zero in its spectrum is an eigenvalue. Furthermore, a compact self-adjoint operator can be diagonalized by its eigenvectors. If is compact, so is . Applying the diagonalization result, the unitary image of its positive square root has a set of orthonormal eigenvectors corresponding to strictly positive eigenvalues . For any in

where the series converges in the norm topology on Notice how this resembles the expression from the finite-dimensional case. are called the singular values of (resp. ) can be considered the left-singular (resp. right-singular) vectors of

Compact operators on a Hilbert space are the closure of finite-rank operators in the uniform operator topology. The above series expression gives an explicit such representation. An immediate consequence of this is:

- Theorem. is compact if and only if is compact.

History

The singular value decomposition was originally developed by differential geometers, who wished to determine whether a real bilinear form could be made equal to another by independent orthogonal transformations of the two spaces it acts on. Eugenio Beltrami and Camille Jordan discovered independently, in 1873 and 1874 respectively, that the singular values of the bilinear forms, represented as a matrix, form a complete set of invariants for bilinear forms under orthogonal substitutions. James Joseph Sylvester also arrived at the singular value decomposition for real square matrices in 1889, apparently independently of both Beltrami and Jordan. Sylvester called the singular values the canonical multipliers of the matrix The fourth mathematician to discover the singular value decomposition independently is Autonne in 1915, who arrived at it via the polar decomposition. The first proof of the singular value decomposition for rectangular and complex matrices seems to be by Carl Eckart and Gale J. Young in 1936;Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag resembling closely the Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm, which uses plane rotations or Givens rotations. However, these were replaced by the method of Gene Golub and William Kahan published in 1965,[26] which uses Householder transformations or reflections. In 1970, Golub and Christian Reinsch published a variant of the Golub/Kahan algorithm[37] that is still the one most-used today.

See also

- Autoencoder

- Canonical correlation

- Canonical form

- Correspondence analysis (CA)

- Curse of dimensionality

- Digital signal processing

- Dimensionality reduction

- Eigendecomposition of a matrix

- Empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs)

- Fourier analysis

- Generalized singular value decomposition

- Inequalities about singular values

- K-SVD

- Latent semantic analysis

- Latent semantic indexing

- Linear least squares

- List of Fourier-related transforms

- Locality-sensitive hashing

- Low-rank approximation

- Matrix decomposition

- Multilinear principal component analysis (MPCA)

- Nearest neighbor search

- Non-linear iterative partial least squares

- Polar decomposition

- Principal component analysis (PCA)

- Schmidt decomposition

- Smith normal form

- Singular value

- Time series

- Two-dimensional singular-value decomposition (2DSVD)

- von Neumann's trace inequality

- Wavelet compression

Notes

- ↑ Although, it was later found to have been known to earlier authors; see Stewart (1993).

- ↑ To see this, we just have to notice that and remember that .

Footnotes

- ↑ Holmes, Mark (2023). Introduction to Scientific Computing and Data Analysis, 2nd Ed. Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-22429-4.

- ↑ DeAngelis, G. C.; Ohzawa, I.; Freeman, R. D. (October 1995). "Receptive-field dynamics in the central visual pathways". Trends Neurosci. 18 (10): 451–8. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(95)94496-R. PMID 8545912.

- ↑ Depireux, D. A.; Simon, J. Z.; Klein, D. J.; Shamma, S. A. (March 2001). "Spectro-temporal response field characterization with dynamic ripples in ferret primary auditory cortex". J. Neurophysiol. 85 (3): 1220–34. doi:10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1220. PMID 11247991.

- ↑ The Singular Value Decomposition in Symmetric (Lowdin) Orthogonalization and Data Compression

- ↑ Golub & Van Loan (1996), §12.4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hastie, Tibshirani & Friedman (2009), pp. 535–536.

- ↑ Sahidullah, Md.; Kinnunen, Tomi (March 2016). "Local spectral variability features for speaker verification". Digital Signal Processing 50: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2015.10.011. Bibcode: 2016DSP....50....1S. https://erepo.uef.fi/handle/123456789/4375.

- ↑ Mademlis, Ioannis; Tefas, Anastasios; Pitas, Ioannis (2018). "Regularized SVD-Based Video Frame Saliency for Unsupervised Activity Video Summarization". 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE. pp. 2691–2695. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2018.8462274. ISBN 978-1-5386-4658-8.

- ↑ Alter, O.; Brown, P. O.; Botstein, D. (September 2000). "Singular Value Decomposition for Genome-Wide Expression Data Processing and Modeling". PNAS 97 (18): 10101–10106. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.18.10101. PMID 10963673. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9710101A.

- ↑ Alter, O.; Golub, G. H. (November 2004). "Integrative Analysis of Genome-Scale Data by Using Pseudoinverse Projection Predicts Novel Correlation Between DNA Replication and RNA Transcription". PNAS 101 (47): 16577–16582. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406767101. PMID 15545604. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10116577A.

- ↑ Alter, O.; Golub, G. H. (August 2006). "Singular Value Decomposition of Genome-Scale mRNA Lengths Distribution Reveals Asymmetry in RNA Gel Electrophoresis Band Broadening". PNAS 103 (32): 11828–11833. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604756103. PMID 16877539. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10311828A.

- ↑ Bertagnolli, N. M.; Drake, J. A.; Tennessen, J. M.; Alter, O. (November 2013). "SVD Identifies Transcript Length Distribution Functions from DNA Microarray Data and Reveals Evolutionary Forces Globally Affecting GBM Metabolism". PLOS ONE 8 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078913. Highlight. PMID 24282503. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...878913B.

- ↑ Edelman, Alan (1992). "On the distribution of a scaled condition number". Math. Comp. 58 (197): 185–190. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1992-1106966-2. Bibcode: 1992MaCom..58..185E. http://math.mit.edu/~edelman/publications/distribution_of_a_scaled.pdf.

- ↑ Shen, Jianhong (Jackie) (2001). "On the singular values of Gaussian random matrices". Linear Alg. Appl. 326 (1–3): 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0024-3795(00)00322-0.

- ↑ Walton, S.; Hassan, O.; Morgan, K. (2013). "Reduced order modelling for unsteady fluid flow using proper orthogonal decomposition and radial basis functions". Applied Mathematical Modelling 37 (20–21): 8930–8945. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2013.04.025.

- ↑ Setyawati, Y.; Ohme, F.; Khan, S. (2019). "Enhancing gravitational waveform model through dynamic calibration". Physical Review D 99 (2). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.99.024010. Bibcode: 2019PhRvD..99b4010S.

- ↑ Sarwar, Badrul; Karypis, George; Konstan, Joseph A.; Riedl, John T. (2000). Application of Dimensionality Reduction in Recommender System – A Case Study (Technical report 00-043). University of Minnesota. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/tr/ADA439541.

- ↑ Bosagh Zadeh, Reza; Carlsson, Gunnar (2013). "Dimension Independent Matrix Square Using MapReduce". arXiv:1304.1467 [cs.DS].

- ↑ Fanaee Tork, Hadi; Gama, João (September 2014). "Eigenspace method for spatiotemporal hotspot detection". Expert Systems 32 (3): 454–464. doi:10.1111/exsy.12088. Bibcode: 2014arXiv1406.3506F.

- ↑ Fanaee Tork, Hadi; Gama, João (May 2015). "EigenEvent: An Algorithm for Event Detection from Complex Data Streams in Syndromic Surveillance". Intelligent Data Analysis 19 (3): 597–616. doi:10.3233/IDA-150734.

- ↑ Muralidharan, Vivek; Howell, Kathleen (2023). "Stretching directions in cislunar space: Applications for departures and transfer design". Astrodynamics 7 (2): 153–178. doi:10.1007/s42064-022-0147-z. Bibcode: 2023AsDyn...7..153M.

- ↑ Muralidharan, Vivek; Howell, Kathleen (2022). "Leveraging stretching directions for stationkeeping in Earth-Moon halo orbits". Advances in Space Research 69 (1): 620–646. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2021.10.028. Bibcode: 2022AdSpR..69..620M.

- ↑ Albers, Jasper; Kurth, Anno; Gutzen, Robin; Morales-Gregorio, Aitor; Denker, Michael; Gruen, Sonja; van Albada, Sacha; Diesmann, Markus (2025). "Assessing the Similarity of Real Matrices with Arbitrary Shape". PRX Life 3 (2). doi:10.1103/PRXLife.3.023005. Bibcode: 2025PRXL....3b3005A.

- ↑ Rijk, P.P.M. de (1989). "A one-sided Jacobi algorithm for computing the singular value decomposition on a vector computer". SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 10 (2): 359–371. doi:10.1137/0910023.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Trefethen & Bau (1997), Lecture 31.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Golub & Kahan (1965).

- ↑ Anderson et al. (1999), 'DBDSQR' source.

- ↑ Demmel & Kahan (1990).

- ↑ Anderson et al. (1999), 'DGESVD' source.

- ↑ GSL Team (2007).

- ↑ Golub & Van Loan (1996), §8.6.3.

- ↑ mathworks.co.kr/matlabcentral/fileexchange/12674-simple-svd

- ↑ Bai, Zhaojun; Demmel, James; Dongarra, Jack J.; Ruhe, Axel; van der Vorst, Henk A. (2000). "Decompositions". Templates for the Solution of Algebraic Eigenvalue Problems. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. doi:10.1137/1.9780898719581. ISBN 978-0-89871-471-5. http://www.netlib.org/utk/people/JackDongarra/etemplates/node43.html.

- ↑ Chicco, D; Masseroli, M (2015). "Software suite for gene and protein annotation prediction and similarity search". IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 12 (4): 837–843. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2014.2382127. PMID 26357324. Bibcode: 2015ITCBB..12..837C.

- ↑ Fan, Ky. (1951). "Maximum properties and inequalities for the eigenvalues of completely continuous operators". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 37 (11): 760–766. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.11.760. PMID 16578416. Bibcode: 1951PNAS...37..760F.

- ↑ Uhlmann, Jeffrey (2018), A Generalized Matrix Inverse that is Consistent with Respect to Diagonal Transformations, SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis, 239, pp. 781–800, http://faculty.missouri.edu/uhlmannj/UC-SIMAX-Final.pdf

- ↑ Golub & Reinsch (1970).

References

- Anderson, E.; Bai, Z.; Bischof, C.; Blackford, S.; Demmel, J.; Dongarra, J.; Du Croz, J.; Greenbaum, A. et al. (1999). "LAPACK Users' Guide". Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. https://www.netlib.org/lapack/lug/.

- Banerjee, Sudipto; Roy, Anindya (2014). Linear Algebra and Matrix Analysis for Statistics. Texts in Statistical Science (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1-4200-9538-8.

- Bisgard, James (2021). Analysis and Linear Algebra: The Singular Value Decomposition and Applications. Student Mathematical Library (1st ed.). AMS. ISBN 978-1-4704-6332-8.

- Chicco, D; Masseroli, M (2015). "Software suite for gene and protein annotation prediction and similarity search". IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 12 (4): 837–843. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2014.2382127. PMID 26357324. Bibcode: 2015ITCBB..12..837C.

- Demmel, James; Kahan, William (1990). "Accurate singular values of bidiagonal matrices". SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing 11 (5): 873–912. doi:10.1137/0911052.

- Golub, Gene H.; Kahan, William (1965). "Calculating the singular values and pseudo-inverse of a matrix". Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Series B: Numerical Analysis 2 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1137/0702016. Bibcode: 1965SJNA....2..205G.

- Golub, G. H.; Reinsch, C. (1970). "Singular value decomposition and least squares solutions". Numerische Mathematik 14 (5): 403–420. doi:10.1007/BF02163027.

- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996). Matrix Computations (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins. ISBN 978-0-8018-5414-9.

- GSL Team (2007). "§14.4 Singular Value Decomposition". GNU Scientific Library. Reference Manual. https://www.gnu.org/software/gsl/manual/html_node/Singular-Value-Decomposition.html.

- Halldor, Bjornsson; Venegas, Silvia A. (1997). A manual for EOF and SVD analyses of climate data (Report). Montréal, Québec: McGill University. CCGCR Report No. 97-1. http://brunnur.vedur.is/pub/halldor/TEXT/eofsvd.html.

- Hansen, P. C. (1987). "The truncated SVD as a method for regularization". BIT 27 (4): 534–553. doi:10.1007/BF01937276.

- Hastie, Trevor; Tibshirani, Robert; Friedman, Jerome (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 535–536. ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0.

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1985). "Section 7.3". Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38632-6.

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1991). "Chapter 3". Topics in Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46713-1. https://archive.org/details/topicsinmatrixan0000horn.

- Press, W. H.; Teukolsky, S. A.; Vetterling, W. T.; Flannery, B. P. (2007). "Section 2.6". Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8. http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html?pg=65.

- Samet, H. (2006). Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-369446-1. https://archive.org/details/foundationsofmul00same.

- Strang, G. (1998). "Section 6.7". Introduction to Linear Algebra (3rd ed.). Wellesley-Cambridge Press. ISBN 978-0-9614088-5-5.

- Stewart, G. W. (1993). "On the Early History of the Singular Value Decomposition". SIAM Review 35 (4): 551–566. doi:10.1137/1035134.

- Trefethen, Lloyd N.; Bau, David III (1997). Numerical Linear Algebra. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 978-0-89871-361-9.

- Wall, Michael E.; Rechtsteiner, Andreas; Rocha, Luis M. (2003). "Singular value decomposition and principal component analysis". in Berrar, D. P.; Dubitzky, W.; Granzow, M.. A Practical Approach to Microarray Data Analysis. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer. pp. 91–109. http://public.lanl.gov/mewall/kluwer2002.html.

h

External links

|