Physics:Particle physics and representation theory

| Group theory → Lie groups Lie groups |

|---|

|

There is a natural connection between particle physics and representation theory, as first noted in the 1930s by Eugene Wigner.[1] It links the properties of elementary particles to the structure of Lie groups and Lie algebras. According to this connection, the different quantum states of an elementary particle give rise to an irreducible representation of the Poincaré group. Moreover, the properties of the various particles, including their spectra, can be related to representations of Lie algebras, corresponding to "approximate symmetries" of the universe.

General picture

Symmetries of a quantum system

In quantum mechanics, any particular one-particle state is represented as a vector in a Hilbert space . To help understand what types of particles can exist, it is important to classify the possibilities for allowed by symmetries, and their properties. Let be a Hilbert space describing a particular quantum system and let be a group of symmetries of the quantum system. In a relativistic quantum system, for example, might be the Poincaré group, while for the hydrogen atom, might be the rotation group SO(3). The particle state is more precisely characterized by the associated projective Hilbert space , also called ray space, since two vectors that differ by a nonzero scalar factor correspond to the same physical quantum state represented by a ray in Hilbert space, which is an equivalence class in and, under the natural projection map , an element of .

By definition of a symmetry of a quantum system, there is a group action on . For each , there is a corresponding transformation of . More specifically, if is some symmetry of the system (say, rotation about the x-axis by 12°), then the corresponding transformation of is a map on ray space. For example, when rotating a stationary (zero momentum) spin-5 particle about its center, is a rotation in 3D space (an element of ), while is an operator whose domain and range are each the space of possible quantum states of this particle, in this example the projective space associated with an 11-dimensional complex Hilbert space .

Each map preserves, by definition of symmetry, the ray product on induced by the inner product on ; according to Wigner's theorem, this transformation of comes from a unitary or anti-unitary transformation of . Note, however, that the associated to a given is not unique, but only unique up to a phase factor. The composition of the operators should, therefore, reflect the composition law in , but only up to a phase factor:

- ,

where will depend on and . Thus, the map sending to is a projective unitary representation of , or possibly a mixture of unitary and anti-unitary, if is disconnected. In practice, anti-unitary operators are always associated with time-reversal symmetry.

Ordinary versus projective representations

It is important physically that in general does not have to be an ordinary representation of ; it may not be possible to choose the phase factors in the definition of to eliminate the phase factors in their composition law. An electron, for example, is a spin-one-half particle; its Hilbert space consists of wave functions on with values in a two-dimensional spinor space. The action of on the spinor space is only projective: It does not come from an ordinary representation of . There is, however, an associated ordinary representation of the universal cover of on spinor space.[2]

For many interesting classes of groups , Bargmann's theorem tells us that every projective unitary representation of comes from an ordinary representation of the universal cover of . Actually, if is finite dimensional, then regardless of the group , every projective unitary representation of comes from an ordinary unitary representation of .[3] If is infinite dimensional, then to obtain the desired conclusion, some algebraic assumptions must be made on (see below). In this setting the result is a theorem of Bargmann.[4] Fortunately, in the crucial case of the Poincaré group, Bargmann's theorem applies.[5] (See Wigner's classification of the representations of the universal cover of the Poincaré group.)

The requirement referred to above is that the Lie algebra does not admit a nontrivial one-dimensional central extension. This is the case if and only if the second cohomology group of is trivial. In this case, it may still be true that the group admits a central extension by a discrete group. But extensions of by discrete groups are covers of . For instance, the universal cover is related to through the quotient with the central subgroup being the center of itself, isomorphic to the fundamental group of the covered group.

Thus, in favorable cases, the quantum system will carry a unitary representation of the universal cover of the symmetry group . This is desirable because is much easier to work with than the non-vector space . If the representations of can be classified, much more information about the possibilities and properties of are available.

The Heisenberg case

An example in which Bargmann's theorem does not apply comes from a quantum particle moving in . The group of translational symmetries of the associated phase space, , is the commutative group . In the usual quantum mechanical picture, the symmetry is not implemented by a unitary representation of . After all, in the quantum setting, translations in position space and translations in momentum space do not commute. This failure to commute reflects the failure of the position and momentum operators—which are the infinitesimal generators of translations in momentum space and position space, respectively—to commute. Nevertheless, translations in position space and translations in momentum space do commute up to a phase factor. Thus, we have a well-defined projective representation of , but it does not come from an ordinary representation of , even though is simply connected.

In this case, to obtain an ordinary representation, one has to pass to the Heisenberg group, which is a nontrivial one-dimensional central extension of .

Poincaré group

The group of translations and Lorentz transformations form the Poincaré group, and this group should be a symmetry of a relativistic quantum system (neglecting general relativity effects, or in other words, in flat spacetime). Representations of the Poincaré group are in many cases characterized by a nonnegative mass and a half-integer spin (see Wigner's classification); this can be thought of as the reason that particles have quantized spin. (Note that there are in fact other possible representations, such as tachyons, infraparticles, etc., which in some cases do not have quantized spin or fixed mass.)

Other symmetries

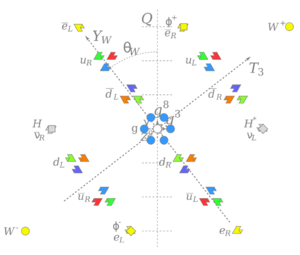

While the spacetime symmetries in the Poincaré group are particularly easy to visualize and believe, there are also other types of symmetries, called internal symmetries. One example is color SU(3), an exact symmetry corresponding to the continuous interchange of the three quark colors.

Lie algebras versus Lie groups

Many (but not all) symmetries or approximate symmetries form Lie groups. Rather than study the representation theory of these Lie groups, it is often preferable to study the closely related representation theory of the corresponding Lie algebras, which are usually simpler to compute.

Now, representations of the Lie algebra correspond to representations of the universal cover of the original group.[6] In the finite-dimensional case—and the infinite-dimensional case, provided that Bargmann's theorem applies—irreducible projective representations of the original group correspond to ordinary unitary representations of the universal cover. In those cases, computing at the Lie algebra level is appropriate. This is the case, notably, for studying the irreducible projective representations of the rotation group SO(3). These are in one-to-one correspondence with the ordinary representations of the universal cover SU(2) of SO(3). The representations of the SU(2) are then in one-to-one correspondence with the representations of its Lie algebra su(2), which is isomorphic to the Lie algebra so(3) of SO(3).

Thus, to summarize, the irreducible projective representations of SO(3) are in one-to-one correspondence with the irreducible ordinary representations of its Lie algebra so(3). The two-dimensional "spin 1/2" representation of the Lie algebra so(3), for example, does not correspond to an ordinary (single-valued) representation of the group SO(3). (This fact is the origin of statements to the effect that "if you rotate the wave function of an electron by 360 degrees, you get the negative of the original wave function.") Nevertheless, the spin 1/2 representation does give rise to a well-defined projective representation of SO(3), which is all that is required physically.

Approximate symmetries

Although the above symmetries are believed to be exact, other symmetries are only approximate.

Hypothetical example

As an example of what an approximate symmetry means, suppose an experimentalist lived inside an infinite ferromagnet, with magnetization in some particular direction. The experimentalist in this situation would find not one but two distinct types of electrons: one with spin along the direction of the magnetization, with a slightly lower energy (and consequently, a lower mass), and one with spin anti-aligned, with a higher mass. Our usual SO(3) rotational symmetry, which ordinarily connects the spin-up electron with the spin-down electron, has in this hypothetical case become only an approximate symmetry, relating different types of particles to each other.

General definition

In general, an approximate symmetry arises when there are very strong interactions that obey that symmetry, along with weaker interactions that do not. In the electron example above, the two "types" of electrons behave identically under the strong and weak forces, but differently under the electromagnetic force.

Example: isospin symmetry

An example from the real world is isospin symmetry, an SU(2) group corresponding to the similarity between up quarks and down quarks. This is an approximate symmetry: while up and down quarks are identical in how they interact under the strong force, they have different masses and different electroweak interactions. Mathematically, there is an abstract two-dimensional vector space

and the laws of physics are approximately invariant under applying a determinant-1 unitary transformation to this space:[7]

For example, would turn all up quarks in the universe into down quarks and vice versa. Some examples help clarify the possible effects of these transformations:

- When these unitary transformations are applied to a proton, it can be transformed into a neutron, or into a superposition of a proton and neutron, but not into any other particles. Therefore, the transformations move the proton around a two-dimensional space of quantum states. The proton and neutron are called an "isospin doublet", mathematically analogous to how a spin-½ particle behaves under ordinary rotation.

- When these unitary transformations are applied to any of the three pions (π0, π+, and π−), it can change any of the pions into any other, but not into any non-pion particle. Therefore, the transformations move the pions around a three-dimensional space of quantum states. The pions are called an "isospin triplet", mathematically analogous to how a spin-1 particle behaves under ordinary rotation.

- These transformations have no effect at all on an electron, because it contains neither up nor down quarks. The electron is called an isospin singlet, mathematically analogous to how a spin-0 particle behaves under ordinary rotation.

In general, particles form isospin multiplets, which correspond to irreducible representations of the Lie algebra SU(2). Particles in an isospin multiplet have very similar but not identical masses, because the up and down quarks are very similar but not identical.

Example: flavour symmetry

Isospin symmetry can be generalized to flavour symmetry, an SU(3) group corresponding to the similarity between up quarks, down quarks, and strange quarks.[7] This is, again, an approximate symmetry, violated by quark mass differences and electroweak interactions—in fact, it is a poorer approximation than isospin, because of the strange quark's noticeably higher mass.

Nevertheless, particles can indeed be neatly divided into groups that form irreducible representations of the Lie algebra SU(3), as first noted by Murray Gell-Mann and independently by Yuval Ne'eman.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Wigner received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of the atomic nucleus and the elementary particles, particularly through the discovery and application of fundamental symmetry principles"; see also Wigner's theorem, Wigner's classification.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 4.7

- ↑ Hall 2013 Theorem 16.47

- ↑ Bargmann, V. (1954). "On unitary ray representations of continuous groups". Ann. of Math. 59 (1): 1–46. doi:10.2307/1969831.

- ↑ Weinberg 1995 Chapter 2, Appendix A and B.

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 5.7

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lecture notes by Prof. Mark Thomson

References

- Coleman, Sidney (1985) Aspects of Symmetry: Selected Erice Lectures of Sidney Coleman. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-26706-4.

- Georgi, Howard (1999) Lie Algebras in Particle Physics. Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Books. ISBN 0-7382-0233-9.

- Hall, Brian C. (2013), Quantum Theory for Mathematicians, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 267, Springer, ISBN 978-1461471158.

- Hall, Brian C. (2015), Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 222 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3319134666.

- Sternberg, Shlomo (1994) Group Theory and Physics. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-24870-1. Especially pp. 148–150.

- Weinberg, Steven (1995). The Quantum Theory of Fields, Volume 1: Foundations. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-55001-7. https://archive.org/details/quantumtheoryoff00stev. Especially appendices A and B to Chapter 2.

External links

- Baez, John C.; Huerta, John (2010). "The Algebra of Grand Unified Theories". Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 47 (3): 483–552. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-10-01294-2.

|