Physics:Photon polarization

Photon polarization is the quantum mechanical description of the classical polarized sinusoidal plane electromagnetic wave. An individual photon can be described as having right or left circular polarization, or a superposition of the two. Equivalently, a photon can be described as having horizontal or vertical linear polarization, or a superposition of the two.

The description of photon polarization contains many of the physical concepts and much of the mathematical machinery of more involved quantum descriptions, such as the quantum mechanics of an electron in a potential well. Polarization is an example of a qubit degree of freedom, which forms a fundamental basis for an understanding of more complicated quantum phenomena. Much of the mathematical machinery of quantum mechanics, such as state vectors, probability amplitudes, unitary operators, and Hermitian operators, emerge naturally from the classical Maxwell's equations in the description. The quantum polarization state vector for the photon, for instance, is identical with the Jones vector, usually used to describe the polarization of a classical wave. Unitary operators emerge from the classical requirement of the conservation of energy of a classical wave propagating through lossless media that alter the polarization state of the wave. Hermitian operators then follow for infinitesimal transformations of a classical polarization state.

Many of the implications of the mathematical machinery are easily verified experimentally. In fact, many of the experiments can be performed with polaroid sunglass lenses.

The connection with quantum mechanics is made through the identification of a minimum packet size, called a photon, for energy in the electromagnetic field. The identification is based on the theories of Planck and the interpretation of those theories by Einstein. The correspondence principle then allows the identification of momentum and angular momentum (called spin), as well as energy, with the photon.

Polarization of classical electromagnetic waves

Polarization states

Linear polarization

The wave is linearly polarized (or plane polarized) when the phase angles are equal,

This represents a wave with phase polarized at an angle with respect to the x axis. In this case the Jones vector

can be written with a single phase:

The state vectors for linear polarization in x or y are special cases of this state vector.

If unit vectors are defined such that

and

then the linearly polarized polarization state can be written in the "x-y basis" as

Circular polarization

If the phase angles and differ by exactly and the x amplitude equals the y amplitude the wave is circularly polarized. The Jones vector then becomes

where the plus sign indicates left circular polarization and the minus sign indicates right circular polarization. In the case of circular polarization, the electric field vector of constant magnitude rotates in the x-y plane.

If unit vectors are defined such that

and

then an arbitrary polarization state can be written in the "R-L basis" as

where

and

We can see that

Elliptical polarization

The general case in which the electric field rotates in the x-y plane and has variable magnitude is called elliptical polarization. The state vector is given by

Geometric visualization of an arbitrary polarization state

To get an understanding of what a polarization state looks like, one can observe the orbit that is made if the polarization state is multiplied by a phase factor of and then having the real parts of its components interpreted as x and y coordinates respectively. That is:

If only the traced out shape and the direction of the rotation of (x(t), y(t)) is considered when interpreting the polarization state, i.e. only

(where x(t) and y(t) are defined as above) and whether it is overall more right circularly or left circularly polarized (i.e. whether |ψR| > |ψL| or vice versa), it can be seen that the physical interpretation will be the same even if the state is multiplied by an arbitrary phase factor, since

and the direction of rotation will remain the same. In other words, there is no physical difference between two polarization states and , between which only a phase factor differs.

It can be seen that for a linearly polarized state, M will be a line in the xy plane, with length 2 and its middle in the origin, and whose slope equals to tan(θ). For a circularly polarized state, M will be a circle with radius 1/√2 and with the middle in the origin.

Energy, momentum, and angular momentum of a classical electromagnetic wave

Energy density of classical electromagnetic waves

Energy in a plane wave

The energy per unit volume in classical electromagnetic fields is (cgs units) and also Planck unit

For a plane wave, this becomes

where the energy has been averaged over a wavelength of the wave.

Fraction of energy in each component

The fraction of energy in the x component of the plane wave is

with a similar expression for the y component resulting in .

The fraction in both components is

Momentum density of classical electromagnetic waves

The momentum density is given by the Poynting vector

For a sinusoidal plane wave traveling in the z direction, the momentum is in the z direction and is related to the energy density:

The momentum density has been averaged over a wavelength.

Angular momentum density of classical electromagnetic waves

Electromagnetic waves can have both orbital and spin angular momentum.[1] The total angular momentum density is

For a sinusoidal plane wave propagating along axis the orbital angular momentum density vanishes. The spin angular momentum density is in the direction and is given by

where again the density is averaged over a wavelength.

Optical filters and crystals

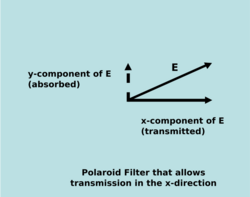

Passage of a classical wave through a polaroid filter

A linear filter transmits one component of a plane wave and absorbs the perpendicular component. In that case, if the filter is polarized in the x direction, the fraction of energy passing through the filter is

Example of energy conservation: Passage of a classical wave through a birefringent crystal

An ideal birefringent crystal transforms the polarization state of an electromagnetic wave without loss of wave energy. Birefringent crystals therefore provide an ideal test bed for examining the conservative transformation of polarization states. Even though this treatment is still purely classical, standard quantum tools such as unitary and Hermitian operators that evolve the state in time naturally emerge.

Initial and final states

A birefringent crystal is a material that has an optic axis with the property that the light has a different index of refraction for light polarized parallel to the axis than it has for light polarized perpendicular to the axis. Light polarized parallel to the axis are called "extraordinary rays" or "extraordinary photons", while light polarized perpendicular to the axis are called "ordinary rays" or "ordinary photons". If a linearly polarized wave impinges on the crystal, the extraordinary component of the wave will emerge from the crystal with a different phase than the ordinary component. In mathematical language, if the incident wave is linearly polarized at an angle with respect to the optic axis, the incident state vector can be written

and the state vector for the emerging wave can be written

While the initial state was linearly polarized, the final state is elliptically polarized. The birefringent crystal alters the character of the polarization.

Dual of the final state

The initial polarization state is transformed into the final state with the operator U. The dual of the final state is given by

where is the adjoint of U, the complex conjugate transpose of the matrix.

Unitary operators and energy conservation

The fraction of energy that emerges from the crystal is

In this ideal case, all the energy impinging on the crystal emerges from the crystal. An operator U with the property that

where I is the identity operator and U is called a unitary operator. The unitary property is necessary to ensure energy conservation in state transformations.

Hermitian operators and energy conservation

If the crystal is very thin, the final state will be only slightly different from the initial state. The unitary operator will be close to the identity operator. We can define the operator H by

and the adjoint by

Energy conservation then requires

This requires that

Operators like this that are equal to their adjoints are called Hermitian or self-adjoint.

The infinitesimal transition of the polarization state is

Thus, energy conservation requires that infinitesimal transformations of a polarization state occur through the action of a Hermitian operator.

Photons: The connection to quantum mechanics

Energy, momentum, and angular momentum of photons

Energy

The treatment to this point has been classical. It is a testament, however, to the generality of Maxwell's equations for electrodynamics that the treatment can be made quantum mechanical with only a reinterpretation of classical quantities. The reinterpretation is based on the theories of Max Planck and the interpretation by Albert Einstein of those theories and of other experiments.[citation needed]

Einstein's conclusion from early experiments on the photoelectric effect is that electromagnetic radiation is composed of irreducible packets of energy, known as photons. The energy of each packet is related to the angular frequency of the wave by the relation

where is an experimentally determined quantity known as Planck's constant. If there are photons in a box of volume , the energy in the electromagnetic field is

and the energy density is

The photon energy can be related to classical fields through the correspondence principle which states that for a large number of photons, the quantum and classical treatments must agree. Thus, for very large , the quantum energy density must be the same as the classical energy density

The number of photons in the box is then

Momentum

The correspondence principle also determines the momentum and angular momentum of the photon. For momentum

where is the wave number. This implies that the momentum of a photon is

Angular momentum and spin

Similarly for the spin angular momentum

where is field strength. This implies that the spin angular momentum of the photon is

the quantum interpretation of this expression is that the photon has a probability of of having a spin angular momentum of and a probability of of having a spin angular momentum of . We can therefore think of the spin angular momentum of the photon being quantized as well as the energy. The angular momentum of classical light has been verified.[2] A photon that is linearly polarized (plane polarized) is in a superposition of equal amounts of the left-handed and right-handed states.

Spin operator

The spin of the photon is defined as the coefficient of in the spin angular momentum calculation. A photon has spin 1 if it is in the state and −1 if it is in the state. The spin operator is defined as the outer product

The eigenvectors of the spin operator are and with eigenvalues 1 and −1, respectively.

The expected value of a spin measurement on a photon is then

An operator S has been associated with an observable quantity, the spin angular momentum. The eigenvalues of the operator are the allowed observable values. This has been demonstrated for spin angular momentum, but it is in general true for any observable quantity.

Spin states

We can write the circularly polarized states as

where s=1 for and s= −1 for . An arbitrary state can be written

where and are phase angles, θ is the angle by which the frame of reference is rotated, and

Spin and angular momentum operators in differential form

When the state is written in spin notation, the spin operator can be written

The eigenvectors of the differential spin operator are

To see this note

The spin angular momentum operator is

The nature of probability in quantum mechanics

Probability for a single photon

There are two ways in which probability can be applied to the behavior of photons; probability can be used to calculate the probable number of photons in a particular state, or probability can be used to calculate the likelihood of a single photon to be in a particular state. The former interpretation violates energy conservation. The latter interpretation is the viable, if nonintuitive, option. Dirac explains this in the context of the double-slit experiment:

Some time before the discovery of quantum mechanics people realized that the connection between light waves and photons must be of a statistical character. What they did not clearly realize, however, was that the wave function gives information about the probability of one photon being in a particular place and not the probable number of photons in that place. The importance of the distinction can be made clear in the following way. Suppose we have a beam of light consisting of a large number of photons split up into two components of equal intensity. On the assumption that the beam is connected with the probable number of photons in it, we should have half the total number going into each component. If the two components are now made to interfere, we should require a photon in one component to be able to interfere with one in the other. Sometimes these two photons would have to annihilate one another and other times they would have to produce four photons. This would contradict the conservation of energy. The new theory, which connects the wave function with probabilities for one photon gets over the difficulty by making each photon go partly into each of the two components. Each photon then interferes only with itself. Interference between two different photons never occurs.

—Paul Dirac, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 1930, Chapter 1

Probability amplitudes

The probability for a photon to be in a particular polarization state depends on the fields as calculated by the classical Maxwell's equations. The polarization state of the photon is proportional to the field. The probability itself is quadratic in the fields and consequently is also quadratic in the quantum state of polarization. In quantum mechanics, therefore, the state or probability amplitude contains the basic probability information. In general, the rules for combining probability amplitudes look very much like the classical rules for composition of probabilities: [The following quote is from Baym, Chapter 1][clarification needed]

- The probability amplitude for two successive probabilities is the product of amplitudes for the individual possibilities. For example, the amplitude for the x polarized photon to be right circularly polarized and for the right circularly polarized photon to pass through the y-polaroid is the product of the individual amplitudes.

- The amplitude for a process that can take place in one of several indistinguishable ways is the sum of amplitudes for each of the individual ways. For example, the total amplitude for the x polarized photon to pass through the y-polaroid is the sum of the amplitudes for it to pass as a right circularly polarized photon, plus the amplitude for it to pass as a left circularly polarized photon,

- The total probability for the process to occur is the absolute value squared of the total amplitude calculated by 1 and 2.

Uncertainty principle

Mathematical preparation

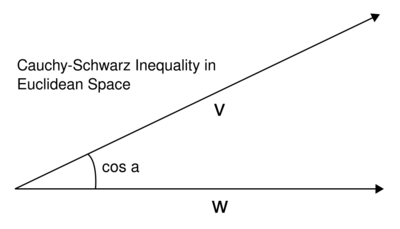

For any legal operators the following inequality, a consequence of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, is true.

If B A ψ and A B ψ are defined, then by subtracting the means and re-inserting in the above formula, we deduce where

is the operator mean of observable X in the system state ψ and

Here

is called the commutator of A and B.

This is a purely mathematical result. No reference has been made to any physical quantity or principle. It simply states that the uncertainty of one operator times the uncertainty of another operator has a lower bound.

Application to angular momentum

The connection to physics can be made if we identify the operators with physical operators such as the angular momentum and the polarization angle. We have then

which means that angular momentum and the polarization angle cannot be measured simultaneously with infinite accuracy. (The polarization angle can be measured by checking whether the photon can pass through a polarizing filter oriented at a particular angle, or a polarizing beam splitter. This results in a yes/no answer which, if the photon was plane-polarized at some other angle, depends on the difference between the two angles.)

States, probability amplitudes, unitary and Hermitian operators, and eigenvectors

Much of the mathematical apparatus of quantum mechanics appears in the classical description of a polarized sinusoidal electromagnetic wave. The Jones vector for a classical wave, for instance, is identical with the quantum polarization state vector for a photon. The right and left circular components of the Jones vector can be interpreted as probability amplitudes of spin states of the photon. Energy conservation requires that the states be transformed with a unitary operation. This implies that infinitesimal transformations are transformed with a Hermitian operator. These conclusions are a natural consequence of the structure of Maxwell's equations for classical waves.

Quantum mechanics enters the picture when observed quantities are measured and found to be discrete rather than continuous. The allowed observable values are determined by the eigenvalues of the operators associated with the observable. In the case angular momentum, for instance, the allowed observable values are the eigenvalues of the spin operator.

These concepts have emerged naturally from Maxwell's equations and Planck's and Einstein's theories. They have been found to be true for many other physical systems. In fact, the typical program is to assume the concepts of this section and then to infer the unknown dynamics of a physical system. This was done, for instance, with the dynamics of electrons. In that case, working back from the principles in this section, the quantum dynamics of particles were inferred, leading to Schrödinger's equation, a departure from Newtonian mechanics. The solution of this equation for atoms led to the explanation of the Balmer series for atomic spectra and consequently formed a basis for all of atomic physics and chemistry.

This is not the only occasion[dubious ] in which Maxwell's equations have forced a restructuring of Newtonian mechanics. Maxwell's equations are relativistically consistent. Special relativity resulted from attempts to make classical mechanics consistent with Maxwell's equations (see, for example, Moving magnet and conductor problem).

See also

- Angular momentum of light

- Quantum decoherence

- Stern–Gerlach experiment

- Wave–particle duality

- Double-slit experiment

- Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation

- Spin polarization

References

- ↑ Allen, L.; Beijersbergen, M.W.; Spreeuw, R.J.C.; Woerdman, J.P. (June 1992). "Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes". Physical Review A 45 (11): 8186–9. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.45.8185. PMID 9906912. Bibcode: 1992PhRvA..45.8185A.

- ↑ Beth, R.A. (1935). "Direct detection of the angular momentum of light". Phys. Rev. 48 (5): 471. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.48.471. Bibcode: 1935PhRv...48..471B.

Further reading

- Jackson, John D. (1998). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- Baym, Gordon (1969). Lectures on Quantum Mechanics. W. A. Benjamin. ISBN 0-8053-0667-6.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1958). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (Fourth ed.). Oxford. ISBN 0-19-851208-2.

|