Physics:Rock mass plasticity

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (November 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In geotechnical engineering, rock mass plasticity is the study of the response of rocks to loads beyond the elastic limit. Historically, conventional wisdom has it that rock is brittle and fails by fracture, while plasticity (irreversible deformation without fracture) is identified with ductile materials such as metals. In field-scale rock masses, structural discontinuities exist in the rock indicating that failure has taken place. Since the rock has not fallen apart, contrary to expectation of brittle behavior, clearly elasticity theory is not the last word.[1]

Theoretically, the concept of rock plasticity is based on soil plasticity which is different from metal plasticity. In metal plasticity, for example in steel, the size of a dislocation is sub-grain size while for soil it is the relative movement of microscopic grains. The theory of soil plasticity was developed in the 1960s at Rice University to provide for inelastic effects not observed in metals. Typical behaviors observed in rocks include strain softening, perfect plasticity, and work hardening.

Application of continuum theory is possible in jointed rocks because of the continuity of tractions across joints even through displacements may be discontinuous. The difference between an aggregate with joints and a continuous solid is in the type of constitutive law and the values of constitutive parameters.

Experimental evidence

Experiments are usually carried out with the intention of characterizing the mechanical behavior of rock in terms of rock strength. The strength is the limit to elastic behavior and delineates the regions where plasticity theory is applicable. Laboratory tests for characterizing rock plasticity fall into four overlapping categories: confining pressure tests, pore pressure or effective stress tests, temperature-dependent tests, and strain rate-dependent tests. Plastic behavior has been observed in rocks using all these techniques since the early 1900s.[2]

The Boudinage experiments [3] show that localized plasticity is observed in certain rock specimens that have failed in shear. Other examples of rock displaying plasticity can be seen in the work of Cheatham and Gnirk.[4] Test using compression and tension show necking of rock specimens while tests using wedge penetration show lip formation. The tests carried out by Robertson [5] show plasticity occurring at high confining pressures. Similar results are observable in the experimental work carried out by Handin and Hager,[6] Paterson,[7] and Mogi.[8] From these results it appears that the transition from elastic to plastic behavior may also indicate the transition from softening to hardening. More evidence is presented by Robinson [9] and Schwartz.[10] It is observed that the higher the confining pressure, the greater the ductility observed. However, the strain to rupture remains roughly the same at around 1.

The effect of temperature on rock plasticity has been explored by several teams of researchers.[11] It is observed that the peak stress decreases with temperature. Extension tests (with confining pressure greater than the compressive stress) show that the intermediate principal stress as well as the strain rate has an effect on the strength. The experiments on the effect of strain rate by Serdengecti and Boozer [12] show that increasing the strain rate makes rock stronger but also makes it appear more brittle. Thus dynamic loading may actually cause the strength of the rock to increase substantially. Increase in temperature appears to increase the rate effect in the plastic behavior of rocks.

After these early explorations in the plastic behavior of rocks, a significant amount of research has been carried out on the subject, primarily by the petroleum industry. From the accumulated evidence, it is clear that rock does exhibit remarkable plasticity under certain conditions and the application of a plasticity theory to rock is appropriate.

Governing equations

The equations that govern the deformation of jointed rocks are the same as those used to describe the motion of a continuum:[13]

where is the mass density, is the material time derivative of , is the particle velocity, is the particle displacement, is the material time derivative of , is the Cauchy stress tensor, is the body force density, is the internal energy per unit mass, is the material time derivative of , is the heat flux vector, is an energy source per unit mass, is the location of the point in the deformed configuration, and t is the time.

In addition to the balance equations, initial conditions, boundary conditions, and constitutive models are needed for a problem to be well-posed. For bodies with internal discontinuities such as jointed rock, the balance of linear momentum is more conveniently expressed in the integral form, also called the principle of virtual work:

where represents the volume of the body and is its surface (including any internal discontinuities), is an admissible variation that satisfies the displacement (or velocity) boundary conditions, the divergence theorem has been used to eliminate derivatives of the stress tensor, and are surface tractions on the surfaces . The jump conditions across stationary internal stress discontinuities require that the tractions across these surfaces be continuous, i.e.,

where are the stresses in the sub-bodies , and is the normal to the surface of discontinuity.

Constitutive relations

For small strains, the kinematic quantity that is used to describe rock mechanics is the small strain tensor If temperature effects are ignored, four types of constitutive relations are typically used to describe small strain deformations of rocks. These relations encompass elastic, plastic, viscoelastic, and viscoplastic behavior and have the following forms:

- Elastic material: or . For an isotropic, linear elastic, material this relation takes the form or . The quantities are the Lamé parameters.

- Viscous fluid: For isotropic materials, or where is the shear viscosity and is the bulk viscosity.

- Nonlinear material: Isotropic nonlinear material relations take the form or . This type of relation is typically used to fit experimental data and may include inelastic behavior.

- Quasi-linear materials: Constitutive relations for these materials are typically expressed in rate form, e.g., or .

A failure criterion or yield surface for the rock may then be expressed in the general form

Typical constitutive relations for rocks assume that the deformation process is isothermal, the material is isotropic, quasi-linear, and homogenous and material properties do not depend upon position at the start of the deformation process, that there is no viscous effect and therefore no intrinsic time scale, that the failure criterion is rate-independent, and that there is no size effect. However, these assumptions are made only to simplify analysis and should be abandoned if necessary for a particular problem.

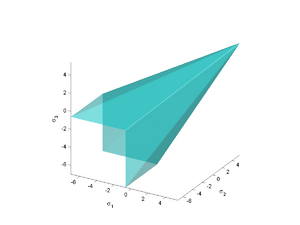

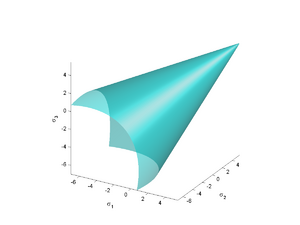

Yield surfaces for rocks

Design of mining and civil structures in rock typically involves a failure criterion that is cohesive-frictional. The failure criterion is used to determine whether a state of stress in the rock will lead to inelastic behavior, including brittle failure. For rocks under high hydrostatic stresses, brittle failure is preceded by plastic deformation and the failure criterion is used to determine the onset of plastic deformation. Typically, perfect plasticity is assumed beyond the yield point. However strain hardening and softening relations with nonlocal inelasticity and damage have also been used. Failure criteria and yield surfaces are also often augmented with a cap to avoid unphysical situations where extreme hydrostatic stress states do not lead to failure or plastic deformation.

Two widely used yield surfaces/failure criteria for rocks are the Mohr-Coulomb model and the Drucker-Prager model. The Hoek–Brown failure criterion is also used, notwithstanding the serious consistency problem with the model. The defining feature of these models is that tensile failure is predicted at low stresses. On the other hand, as the stress state becomes increasingly compressive, failure and yield requires higher and higher values of stress.

Plasticity theory

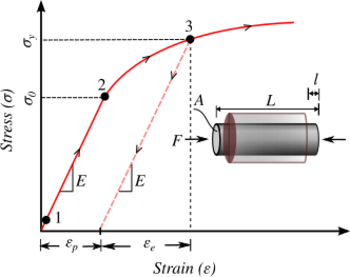

The governing equations, constitutive models, and yield surfaces discussed above are not sufficient if we are to compute the stresses and displacements in a rock body that is undergoing plastic deformation. An additional kinematic assumption is needed, i.e., that the strain in the body can be decomposed additively (or multiplicatively in some cases) into an elastic part and a plastic part. The elastic part of the strain can be computed from a linear elastic constitutive model. However, determination of the plastic part of the strain requires a flow rule and a hardening model.

Typical flow plasticity theories (for small deformation perfect plasticity or hardening plasticity) are developed on the basis on the following requirements:

- The rock has a linear elastic range.

- The rock has an elastic limit defined as the stress at which plastic deformation first takes place, i.e., .

- Beyond the elastic limit the stress state always remains on the yield surface, i.e., .

- Loading is defined as the situation under which increments of stress are greater than zero, i.e., . If loading takes the stress state to the plastic domain then the increment of plastic strain is always greater than zero, i.e., .

- Unloading is defined as the situation under which increments of stress are less than zero, i.e., . The material is elastic during unloading and no additional plastic strain is accumulated.

- The total strain is a linear combination of the elastic and plastic parts, i.e., . The plastic part cannot be recovered while the elastic part is fully recoverable.

- The work done of a loading-unloading cycle is positive or zero, i.e., . This is also called the Drucker stability postulate and eliminates the possibility of strain softening behavior.

Three-dimensional plasticity

The above requirements can be expressed in three dimensions as follows.

- Elasticity (Hooke's law). In the linear elastic regime the stresses and strains in the rock are related by

- where the stiffness matrix is constant.

- Elastic limit (Yield surface). The elastic limit is defined by a yield surface that does not depend on the plastic strain and has the form

- Beyond the elastic limit. For strain hardening rocks, the yield surface evolves with increasing plastic strain and the elastic limit changes. The evolving yield surface has the form

- Loading. It is not straightforward to translate the condition geology to three dimensions, particularly for rock plasticity which is dependent not only on the deviatoric stress but also on the mean stress. However, during loading and it is assumed that the direction of plastic strain is identical to the normal to the yield surface () and that , i.e.,

- The above equation, when it is equal to zero, indicates a state of neutral loading where the stress state moves along the yield surface without changing the plastic strain.

- Unloading: A similar argument is made for unloading for which situation , the material is in the elastic domain, and

- Strain decomposition: The additive decomposition of the strain into elastic and plastic parts can be written as

- Stability postulate: The stability postulate is expressed as

Flow rule

In metal plasticity, the assumption that the plastic strain increment and deviatoric stress tensor have the same principal directions is encapsulated in a relation called the flow rule. Rock plasticity theories also use a similar concept except that the requirement of pressure-dependence of the yield surface requires a relaxation of the above assumption. Instead, it is typically assumed that the plastic strain increment and the normal to the pressure-dependent yield surface have the same direction, i.e.,

where is a hardening parameter. This form of the flow rule is called an associated flow rule and the assumption of co-directionality is called the normality condition. The function is also called a plastic potential.

The above flow rule is easily justified for perfectly plastic deformations for which when , i.e., the yield surface remains constant under increasing plastic deformation. This implies that the increment of elastic strain is also zero, , because of Hooke's law. Therefore,

Hence, both the normal to the yield surface and the plastic strain tensor are perpendicular to the stress tensor and must have the same direction.

For a work hardening material, the yield surface can expand with increasing stress. We assume Drucker's second stability postulate which states that for an infinitesimal stress cycle this plastic work is positive, i.e.,

The above quantity is equal to zero for purely elastic cycles. Examination of the work done over a cycle of plastic loading-unloading can be used to justify the validity of the associated flow rule.[14]

Consistency condition

The Prager consistency condition is needed to close the set of constitutive equations and to eliminate the unknown parameter from the system of equations. The consistency condition states that at yield because , and hence

Notes

- ↑ Pariseau (1988).

- ↑ Adams and Coker (1910).

- ↑ Rast (1956).

- ↑ Cheatham and Gnirk (1966).

- ↑ Robertson (1955).

- ↑ Handin and Hager (1957,1958,1963.)

- ↑ Paterson (1958).

- ↑ Mogi (1966).

- ↑ Robinson (1959).

- ↑ Schwartz (1964).

- ↑ Griggs, Turner, Heard (1960)

- ↑ Serdengecti and Boozer (1961)

- ↑ The operators in the governing equations are defined as:

- ↑ Anandarajah (2010).

References

- Pariseau, W. G. (1988), "On the concept of rock mass plasticity", In the 29th US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS) (Balkema)

- Adams, F. D.; Coker, E. G. (1910), "An experimental investigation into the flow of rocks; the flow of marble", American Journal of Science 174 (174): 465–487, doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-29.174.465, Bibcode: 1910AmJS...29..465A, https://zenodo.org/record/1450166

- Rast, Nicholas (1956), "The origin and significance of boudinage.", Geol. Mag. 93 (5): 401–408, doi:10.1017/s001675680006684x, Bibcode: 1956GeoM...93..401R

- Cheatham Jr, J. B.; Gnirk, P. F. (1966), "The mechanics of rock failure associated with drilling at depth", In Proceedings of the Eighth Symposium on Rock Mechanics, Fairhurst C, Editor, University of Minnesota: 410–439

- Robertson, Eugene C. (1955), "Experimental study of the strength of rocks", Geological Society of America Bulletin 66 (10): 1275–1314, doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1955)66[1275:esotso2.0.co;2], Bibcode: 1955GSAB...66.1275R

- Handin, John; Hager Jr., Rex V. (1957), "Experimental deformation of sedimentary rocks under confining pressure: Tests at room temperature on dry samples", AAPG Bulletin 41 (1): 1–50, doi:10.1306/5ceae5fb-16bb-11d7-8645000102c1865d, http://archives.datapages.com/data/bulletns/1957-60/data/pg/0041/0001/0000/0001.htm

- Handin, John; Hager Jr., Rex V. (1958), "Experimental deformation of sedimentary rocks under confining pressure: Tests at high temperature", AAPG Bulletin 42 (12): 2892–2934, doi:10.1306/0bda5c27-16bd-11d7-8645000102c1865d, http://archives.datapages.com/data/bulletns/1957-60/data/pg/0042/0012/2850/2892.htm

- Handin, John; Hager Jr, Rex V.; Friedman, Melvin; Feather, James N. (1963), "Experimental deformation of sedimentary rocks under confining pressure: pore pressure tests", AAPG Bulletin 47 (5): 717–755, doi:10.1306/bc743a87-16be-11d7-8645000102c1865d, http://archives.datapages.com/data/bulletns/1961-64/data/pg/0047/0005/0700/0717.htm

- Paterson, M. S. (1958), "Experimental deformation and faulting in Wombeyan marble", Geological Society of America Bulletin 69 (4): 465–476, doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1958)69[465:edafiw2.0.co;2], Bibcode: 1958GSAB...69..465P

- Mogi, Kiyoo (1966), "Pressure Dependence of Rock Strength and Transition from Brittle Fracture to Ductile Flow", Bulletin of the Earthquake Research Institute 44: 215–232, http://repository.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2261/12246/1/ji0441012.pdf

- Robinson, L. H. (1959), "The effect of pore and confining pressure on the failure process in sedimentary rock", In the 3rd US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS)

- Schwartz, Arnold E (1964), "Failure of rock in the triaxial shear test", In the 6th US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS)

- Griggs, D. T.; Turner, F. J.; Heard, H. C. (1960). "Deformation of rocks at 500 to 800 C". Rock deformation: Geological Society of America Memoir. 39. Geological Society of America. p. 104. doi:10.1130/mem79-p39.

- Serdengecti, S.; Boozer, G. D. (1961), "The effects of strain rate and temperature on the behavior of rocks subjected to triaxial compression", In Proceedings of the Fourth Symposium on Rock Mechanics: 83–97

- Anandarajah, A. (2010), Computational methods in elasticity and plasticity: solids and porous media, Springer

External links

|