Displacement (vector)

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

| [math]\displaystyle{ \textbf{F} = \frac{d}{dt} (m\textbf{v}) }[/math] |

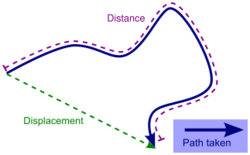

A displacement is a vector whose length is the shortest distance from the initial to the final position of a point P.[1] It quantifies both the distance and direction of an imaginary motion along a straight line from the initial position to the final position of the point. A displacement may be identified with the translation that maps the initial position to the final position.

A displacement may be also described as a 'relative position': the final position of a point (xf) relative to its initial position (xi), and a displacement vector can be mathematically defined as the difference between the final and initial positions:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{s}=\boldsymbol{s_f-s_i}=\Delta\boldsymbol{s} }[/math]

In considering motions of objects over time the instantaneous velocity of the object is the rate of change of the displacement as a function of time. The instantaneous speed then is distinct from velocity, or the time rate of change of the distance traveled along a specific path. The velocity may be equivalently defined as the time rate of change of the position vector. If one considers a moving initial position, or equivalently a moving origin (e.g. an initial position or origin which is fixed to a train wagon, which in turn moves with respect to its rail track), the velocity of P (e.g. a point representing the position of a passenger walking on the train) may be referred to as a relative velocity, as opposed to an absolute velocity, which is computed with respect to a point which is considered to be 'fixed in space' (such as, for instance, a point fixed on the floor of the train station).

For motion over a given interval of time, the displacement divided by the length of the time interval defines the average velocity. (Note that the average velocity, as a vector, differs from the average speed that is the ratio of the path length — a scalar — and the time interval.)

Rigid body

In dealing with the motion of a rigid body, the term displacement may also include the rotations of the body. In this case, the displacement of a particle of the body is called linear displacement (displacement along a line), while the rotation of the body is called angular displacement.[citation needed]

Derivatives

For a position vector s that is a function of time t, the derivatives can be computed with respect to t. These derivatives have common utility in the study of kinematics, control theory, vibration sensing and other sciences and engineering disciplines.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{v}=\frac{\text{d}\boldsymbol{s}}{\text{d}t} }[/math] (where ds is an infinitesimally small displacement)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{a}=\frac{\text{d}\boldsymbol{v}}{\text{d}t}=\frac{\text{d}^2\boldsymbol{s}}{\text{d}t^2} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{j}=\frac{\text{d}\boldsymbol{a}}{\text{d}t}=\frac{\text{d}^2\boldsymbol{v}}{\text{d}t^2}=\frac{\text{d}^3\boldsymbol{s}}{\text{d}t^3} }[/math]

These common names correspond to terminology used in basic kinematics.[2] By extension, the higher order derivatives can be computed in a similar fashion. Study of these higher order derivatives can improve approximations of the original displacement function. Such higher-order terms are required in order to accurately represent the displacement function as a sum of an infinite series, enabling several analytical techniques in engineering and physics. The fourth order derivative is called jounce.

See also

- Equipollence (geometry)

- Position vector

- Affine space

References

- ↑ Tom Henderson. "Describing Motion with Words". The Physics Classroom. http://www.physicsclassroom.com/Class/1DKin/U1L1c.cfm. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Stewart, James (2001). "§2.8 - The Derivative As A Function". Calculus (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-37718-1.