Software:Need for Speed II

| Need for Speed II | |

|---|---|

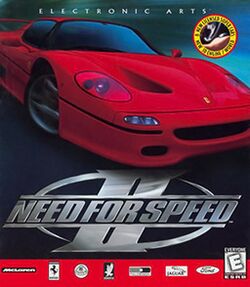

Cover art featuring Ferrari F50 | |

| Developer(s) | EA Canada (PS) EA Seattle (PC) |

| Publisher(s) | Electronic Arts |

| Producer(s) | Hanno Lemke |

| Designer(s) | Scott Blackwood Hanno Lemke |

| Programmer(s) | Laurent Ancessi David Lucas |

| Artist(s) | Scott Jackson Kent Maclagan |

| Writer(s) | Gregg Giles Richard Mul Scott Blackwood |

| Composer(s) | Saki Kaskas Jeff van Dyck Alistair Hirst |

| Series | Need for Speed |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation, Microsoft Windows |

| Release | PlayStation Microsoft Windows |

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Need for Speed II is a 1997 racing video game released for PlayStation and Microsoft Windows. It is the second installment in the Need for Speed series, a sequel Software:Need for Speed III: Hot Pursuit was released in 1998.

Gameplay

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Like its predecessor, Need for Speed II allows players to race exotic cars in country-themed tracks from North America, Europe, Asia and Australia, either against computer-controlled opponents or human opponents via a LAN, modem, serial connection, or in split screen. There are three distinct gameplay modes: Single Race mode in which a player simply chooses a car and a course and completes a single race. In this mode, the player can customize both the number and type of opponents as well as the amount of laps to be completed. Tournament Mode in which the player must complete a series of races successfully to unlock a bonus car. The Knockout Mode consists of a series of 2-lap races with eight opponents; the last-place finisher at the end of each race is eliminated from the competition.

The game features eight real-life high-end sports cars and concept cars which the player can drive and race against. The "Special Edition" release of the game added four additional cars. In addition, the game features a "showcase" that provides photos, videos, and technical information about the cars as well as the history of each company and the background of each car's development.[3]

The game also features several new elements compared to the previous game in the form of customizable car paint and components of their car including gear ratios, tires, and spoilers.

Development

Need for Speed II was developed by EA Canada. The lead programmer for the game was Laurent Ancessi with Wei Shoong Teh and Brad Gour as senior programmers.[4]

EA abandoned the Road & Track license used with the original game in favor of licensing with each automobile manufacturer individually.[3] To ensure the physics of fast car handling and performance were as accurate as possible, the programmers collaborated with the manufactures of each vehicle.[5] The sound effects were created by installing microphones in various positions on each car and recording onto eight track digital tape while the car was driven.[3]

A version for the Panasonic M2 was in the works but it was never released due to the cancellation of the system.[6]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Need for Speed II was met with mixed reviews. Aggregating review websites GameRankings and Metacritic gave the PlayStation version 71.39% and 71/100[4][7] and the PC version 68.25%.[8] Critics were universally impressed with the selection of expensive cars and the huge number of tracks.[lower-alpha 1] However, most found that other issues interfered with enjoyment of the game. IGN, for instance, remarked that "All the right elements are there – cool cars, inventive tracks, decent control – but the execution has been seriously flawed by poor graphics and frame rate."[10] The most commonly cited problem with the graphics was the high amount of pop-in,[14][13][15] which Next Generation said "is actually irritating enough to obfuscate what could be a good time."[13] The Official PlayStation Magazine said the game had "atrocious handling" and that it soon got boring.[11] Several critics noted, usually in the form of a complaint, that the game's handling requires players to frequently brake during turns.[14][13][15]

There was considerable disagreement over the game's blend of realistic and arcade-style racing. In Electronic Gaming Monthly, Kraig Kujawa and Dean Hager's criticism of the game stemmed from it being easier to play and therefore less realistic than its predecessor.[9][16] Kujawa added the game "has been given an arcade edge that simply doesn't fit. The cartoony-looking graphics are subpar because they ruin the realistic feel of driving these real, exotic cars."[9] GamePro, however, stated the reverse, that the gameplay was too realistic to appeal to fans of arcade-style racing, and could only be recommended to players who enjoyed games like Formula 1 and the original Need for Speed.[15] GameSpot's Glenn Rubenstein offered a third opinion, saying it provides a unique middle-ground between realism and arcade-style by allowing players to drive real cars with realistic handling into exotic populated areas. He also praised the music and sound effects, and while acknowledging the issues with the graphics, he found them overall impressive, and concluded Need for Speed II to be "the PlayStation's slickest racer yet".[14]

The PC version was slightly less well-received. An issue was that the game required a fast computer at the time, to display the graphics at the highest setting.[12][16] A reviewer for Computer and Video Games did not appreciate the combination of super realistic cars being driven on fantasy tracks and thought that the crashes "look and feel wrong".[5] Tasos Kaiafas of GameSpot liked the game, but felt most of the roads were "outrageous" and that the cars would be unfamiliar to many.[17] An Adrenaline Vault review described the game as a "good overall driving experience" with easy installation, realistic sound effects and both an excellent interface and music.[12]

A 2007 retrospective review in The Game Goldies praised the crisper graphics, smoother animation, rich colors and increased detail compared to the original.[18]

Special Edition

Released on October 29, 1997, in the United States[19] and February 2, 1998, in Japan and Europe, the special edition of Need for Speed II includes exclusive "Last Resort" track, three extra cars, three bonus cars, a new driving style called "Wild", and 3dfx Glide hardware acceleration support.

Notes

References

- ↑ "Game Informer News". Game Informer. 1999-03-02. http://www.gameinformer.com/news/mar97/033197c.html. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ↑ Staff (April 18, 1997). "EA Ships Need for Speed II". PC Gamer. http://www.pcgamer.com/news/news-1997-04-14.html. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "NG Alphas: Need for Speed 2". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (27): 68–69. March 1997.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Need for Speed II (PlayStation) reviews at". Metacritic. CBS Interactive Inc.. https://www.metacritic.com/game/need-for-speed-ii/critic-reviews/?platform=playstation.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Duncan McDonald (August 13, 2001). "PC Review: Need For Speed 2 Review". Computer and Video Games. Future Publishing Ltd. http://www.computerandvideogames.com/article.php?id=3243.

- ↑ "News – E3 '96: 3DO? - M2 Dream List". 3DO Magazine (Paragon Publishing) (12): 4. July 1996. https://archive.org/details/3DO_Magazine_Issue_12_1996-07_Paragon_Publishing_GB/page/n3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Need for Speed II (PlayStation) reviews". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc.. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130530032945/http://www.gamerankings.com/ps/198112-need-for-speed-ii/index.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Need for Speed II (PC) reviews". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc.. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130518045651/http://www.gamerankings.com/pc/198111-need-for-speed-ii/index.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Team EGM Sports: Need for Speed 2". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis) (96): 114. July 1997.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Need for Speed II". IGN.com. IGN Entertainment, Inc.. April 3, 1997. https://www.ign.com/articles/1997/04/04/need-for-speed-2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Need For Speed 2 review, Official UK PlayStation Magazine, Future Publishing, June 1997, issue 20, page 117

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Shawn Quigley (May 11, 1997). "Need for Speed 2 PC review". Adrenaline Vault. NewWorld.com, Inc.. http://www.avault.com/reviews/pc/need-for-speed-2-pc-review/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "Need for Speed II". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (32): 116. August 1997.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGSPS - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Air Hendrix (June 1997). "PlayStation ProReview: Need for Speed II". GamePro (IDG) (105): 70.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Navneet Prakash (March 22, 2008). "The Evolution of Need for Speed". techtree.com. UNML. http://www.techtree.com/India/Reviews/The_Evolution_of_Need_for_Speed/551-87812-699-1.html.

- ↑ Kaiafas, Tasos (May 15, 1997). "Need for Speed II Review for PC". CBS Interactive Inc.. http://www.gamespot.com/reviews/need-for-speed-ii-review/1900-2543786/.

- ↑ "The Need for Speed 2 by Electronic Arts. NFS 2 Download and Review". Old Games Collection. November 5, 2007. http://www.gamegoldies.org/download-nfs2-ea-need-for-speed-2-review/.

- ↑ Staff (October 29, 1997). "Now Shipping". PC Gamer. http://www.pcgamer.com/news/news-1997-10-27.html. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

"Three games from Electronic Arts: ...and Need for Speed II -- Special Edition."

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|