Medicine:Cognitive behavioral therapy

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | |

|---|---|

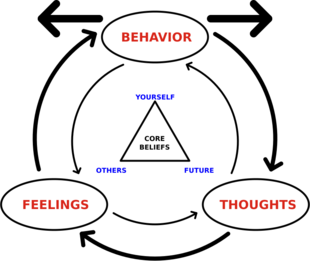

The triangle in the middle represents CBT's tenet that all humans' core beliefs can be summed up in three categories: self, others, future. | |

| ICD-10-PCS | GZ58ZZZ |

| MeSH | D015928 |

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social intervention[1][2] that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders.[3] Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most effective means of treatment for substance abuse and co-occurring mental health disorders.[4] CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions (such as thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes) and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation[2][5] and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed to treat depression, its uses have been expanded to include many issues and the treatment of many mental health conditions, including anxiety,[6][7] substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders.[8][9][10][11] CBT includes a number of cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies that treat defined psychopathologies using evidence-based techniques and strategies.[12][13][14]

CBT is a common form of talk therapy based on the combination of the basic principles from behavioral and cognitive psychology.[2] It is different from historical approaches to psychotherapy, such as the psychoanalytic approach where the therapist looks for the unconscious meaning behind the behaviors and then formulates a diagnosis. Instead, CBT is a "problem-focused" and "action-oriented" form of therapy, meaning it is used to treat specific problems related to a diagnosed mental disorder. The therapist's role is to assist the client in finding and practicing effective strategies to address the identified goals and to alleviate symptoms of the disorder.[15] CBT is based on the belief that thought distortions and maladaptive behaviors play a role in the development and maintenance of many psychological disorders[3] and that symptoms and associated distress can be reduced by teaching new information-processing skills and coping mechanisms.[1][15][16]

When compared to psychoactive medications, review studies have found CBT alone to be as effective for treating less severe forms of depression,[17] anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), tics,[18] substance use disorders, eating disorders, and borderline personality disorder.[19] Some research suggests that CBT is most effective when combined with medication for treating mental disorders, such as major depressive disorder.[20] CBT is recommended as the first line of treatment for the majority of psychological disorders in children and adolescents, including aggression and conduct disorder.[1][5] Researchers have found that other bona fide therapeutic interventions were equally effective for treating certain conditions in adults.[21][22] Along with interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), CBT is recommended in treatment guidelines as a psychosocial treatment of choice.[1][23]

History

Early roots

The prevailing body of research consistently indicates that maintaining a faith or belief system generally contributes positively to mental well-being.[24] Religious institutions have proactively established charities, such as the Samaritans, to address mental health issues.[25] Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has undergone scrutiny as studies investigating the impact of religious belief and practices have gained prominence. Numerous randomized controlled trials have explored the correlation of CBT within diverse religious frameworks, including Judaism,[26] Taoism,[27] and predominantly, Christianity.[28][29][30][31]

Islam

Islamic psychology, rooted in the Sufi tradition, traces its origins to the 11th century, notably shaped by Al Ghazali. Al Ghazali conceptualized the self with four integral elements: heart, spirit, soul, and intellect. These components align correspondingly with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) domains, specifically emotions, behaviors, thoughts, and the capacity for reflection.[32]

Buddhism

Principles originating from Buddhism have significantly impacted the evolution of various new forms of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), including Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, Spirituality-Based CBT, and Compassion Focused Therapy.[33]

Philosophy

Precursors of certain fundamental aspects of CBT have been identified in various ancient philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism.[34] Stoic philosophers, particularly Epictetus, believed logic could be used to identify and discard false beliefs that lead to destructive emotions, which has influenced the way modern cognitive-behavioral therapists identify cognitive distortions that contribute to depression and anxiety. Aaron T. Beck's original treatment manual for depression states, "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers".[35] Another example of Stoic influence on cognitive theorists is Epictetus on Albert Ellis.[36] A key philosophical figure who influenced the development of CBT was John Stuart Mill through his creation of Associationism, a predecessor of classical conditioning and behavioral theory.[37][38]

The modern roots of CBT can be traced to the development of behavior therapy in the early 20th century, the development of cognitive therapy in the 1960s, and the subsequent merging of the two.

Behavioral therapy

Groundbreaking work of behaviorism began with John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner's studies of conditioning in 1920.[39] Behaviorally-centered therapeutic approaches appeared as early as 1924[40] with Mary Cover Jones' work dedicated to the unlearning of fears in children.[41] These were the antecedents of the development of Joseph Wolpe's behavioral therapy in the 1950s.[39] It was the work of Wolpe and Watson, which was based on Ivan Pavlov's work on learning and conditioning, that influenced Hans Eysenck and Arnold Lazarus to develop new behavioral therapy techniques based on classical conditioning.[39][42]

During the 1950s and 1960s, behavioral therapy became widely used by researchers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa. Their inspiration was by the behaviorist learning theory of Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and Clark L. Hull.[40]

In Britain, Joseph Wolpe, who applied the findings of animal experiments to his method of systematic desensitization,[39] applied behavioral research to the treatment of neurotic disorders. Wolpe's therapeutic efforts were precursors to today's fear reduction techniques.[40] British psychologist Hans Eysenck presented behavior therapy as a constructive alternative.[40][43]

At the same time as Eysenck's work, B. F. Skinner and his associates were beginning to have an impact with their work on operant conditioning.[39][42] Skinner's work was referred to as radical behaviorism and avoided anything related to cognition.[39] However, Julian Rotter in 1954 and Albert Bandura in 1969 contributed to behavior therapy with their works on social learning theory by demonstrating the effects of cognition on learning and behavior modification.[39][42] The work of Claire Weekes in dealing with anxiety disorders in the 1960s is also seen as a prototype of behavior therapy.[44]

The emphasis on behavioral factors has been described as the "first wave" of CBT.[45]

Cognitive therapy

One of the first therapists to address cognition in psychotherapy was Alfred Adler, notably with his idea of basic mistakes and how they contributed to creation of unhealthy behavioral and life goals.[46]Abraham Low believed that someone's thoughts were best changed by changing their actions.[47] Adler and Low influenced the work of Albert Ellis,[46][48] who developed the earliest cognitive-based psychotherapy called rational emotive behavioral therapy, or REBT.[49] The first version of REBT was announced to the public in 1956.

In the late 1950s, Aaron T. Beck was conducting free association sessions in his psychoanalytic practice.[50][51] During these sessions, Beck noticed that thoughts were not as unconscious as Freud had previously theorized, and that certain types of thinking may be the culprits of emotional distress.[51] It was from this hypothesis that Beck developed cognitive therapy, and called these thoughts "automatic thoughts".[51] He first published his new methodology in 1967, and his first treatment manual in 1979.[50] Beck has been referred to as "the father of cognitive behavioral therapy".[52]

It was these two therapies, rational emotive therapy, and cognitive therapy, that started the "second wave" of CBT, which emphasized cognitive factors.[45]

Merger of behavioral and cognitive therapies

Although the early behavioral approaches were successful in many so-called neurotic disorders, they had little success in treating depression.[39][40][53] Behaviorism was also losing popularity due to the cognitive revolution. The therapeutic approaches of Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck gained popularity among behavior therapists, despite the earlier behaviorist rejection of mentalistic concepts like thoughts and cognitions.[39] Both of these systems included behavioral elements and interventions, with the primary focus being on problems in the present.

In initial studies, cognitive therapy was often contrasted with behavioral treatments to see which was most effective. During the 1980s and 1990s, cognitive and behavioral techniques were merged into cognitive behavioral therapy. Pivotal to this merging was the successful development of treatments for panic disorder by David M. Clark in the UK and David H. Barlow in the US.[40]

Over time, cognitive behavior therapy came to be known not only as a therapy, but as an umbrella term for all cognitive-based psychotherapies.[39] These therapies include, but are not limited to, REBT, cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, metacognitive therapy, metacognitive training, reality therapy/choice theory, cognitive processing therapy, EMDR, and multimodal therapy.[39]

This blending of theoretical and technical foundations from both behavior and cognitive therapies constituted the "third wave" of CBT.[54][45] The most prominent therapies of this third wave are dialectical behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy.[45] Despite the increasing popularity of third-wave treatment approaches, reviews of studies reveal there may be no difference in the effectiveness compared with non-third wave CBT for the treatment of depression.[55]

Medical uses

In adults, CBT has been shown to be an effective part of treatment plans for anxiety disorders,[56][57] body dysmorphic disorder,[58] depression,[59][60][61] eating disorders,[8][62][61] chronic low back pain,[63] personality disorders,[64][61] psychosis,[65] schizophrenia,[66][61] substance use disorders,[67][61] and bipolar disorder.[61] It is also effective as part of treatment plans in the adjustment, depression, and anxiety associated with fibromyalgia,[68] and with post-spinal cord injuries.[69]

In children or adolescents, CBT is an effective part of treatment plans for anxiety disorders,[70] body dysmorphic disorder,[71] depression and suicidality,[72] eating disorders[8] and obesity,[73] obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[74] and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[75] as well as tic disorders, trichotillomania, and other repetitive behavior disorders.[76] CBT has also been applied to a variety of childhood disorders,[77] including depressive disorders and various anxiety disorders. CBT has shown to be the most effective intervention for people exposed to adverse childhood experiences in the form of abuse or neglect.[78]

Criticism of CBT sometimes focuses on implementations (such as the UK IAPT) which may result initially in low quality therapy being offered by poorly trained practitioners.[79][80] However, evidence supports the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety and depression.[81]

Evidence suggests that the addition of hypnotherapy as an adjunct to CBT improves treatment efficacy for a variety of clinical issues.[82][83][84]

The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends CBT in the treatment plans for a number of mental health difficulties, including PTSD, OCD, bulimia nervosa, and clinical depression.[85]

Depression and anxiety disorders

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown as an effective treatment for clinical depression.[59] The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines (April 2000) indicated that, among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy had the best-documented efficacy for treatment of major depressive disorder.[86][page needed]

A 2001 meta-analysis comparing CBT and psychodynamic psychotherapy suggested the approaches were equally effective in the short term for depression.[87] In contrast, a 2013 meta-analyses suggested that CBT, interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving therapy outperformed psychodynamic psychotherapy and behavioral activation in the treatment of depression.[23]

According to a 2004 review by INSERM of three methods, cognitive behavioral therapy was either proven or presumed to be an effective therapy on several mental disorders.[61] This included depression, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress, and other anxiety disorders.[61]

CBT has been shown to be effective in the treatment of adults with anxiety disorders.[88] In a 2020 Cochrane review it was determined that CBT for children and adolescents was probably more effective (short term) than wait list or no treatment and more effective than attention control.[89]

Results from a 2018 systematic review found a high strength of evidence that CBT-exposure therapy can reduce PTSD symptoms and lead to the loss of a PTSD diagnosis.[90] CBT has also been shown to be effective for post-traumatic stress disorder in very young children (3 to 6 years of age).[91] A Cochrane review found low quality evidence that CBT may be more effective than other psychotherapies in reducing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents.[92]

A systematic review of CBT in depression and anxiety disorders concluded that "CBT delivered in primary care, especially including computer- or Internet-based self-help programs, is potentially more effective than usual care and could be delivered effectively by primary care therapists."[93]

Some meta-analyses find CBT more effective than psychodynamic therapy and equal to other therapies in treating anxiety and depression.[94][95]

Theoretical approaches

One etiological theory of depression is Aaron T. Beck's cognitive theory of depression. His theory states that depressed people think the way they do because their thinking is biased towards negative interpretations. According to this theory, depressed people acquire a negative schema of the world in childhood and adolescence as an effect of stressful life events, and the negative schema is activated later in life when the person encounters similar situations.[96]

Beck also described a negative cognitive triad. The cognitive triad is made up of the depressed individual's negative evaluations of themselves, the world, and the future. Beck suggested that these negative evaluations derive from the negative schemata and cognitive biases of the person. According to this theory, depressed people have views such as "I never do a good job", "It is impossible to have a good day", and "things will never get better". A negative schema helps give rise to the cognitive bias, and the cognitive bias helps fuel the negative schema. Beck further proposed that depressed people often have the following cognitive biases: arbitrary inference, selective abstraction, overgeneralization, magnification, and minimization. These cognitive biases are quick to make negative, generalized, and personal inferences of the self, thus fueling the negative schema.[96]

A basic concept in some CBT treatments used in anxiety disorders is in vivo exposure. CBT-exposure therapy refers to the direct confrontation of feared objects, activities, or situations by a patient. For example, a woman with PTSD who fears the location where she was assaulted may be assisted by her therapist in going to that location and directly confronting those fears.[97] Likewise, a person with a social anxiety disorder who fears public speaking may be instructed to directly confront those fears by giving a speech.[98] This "two-factor" model is often credited to O. Hobart Mowrer.[99] Through exposure to the stimulus, this harmful conditioning can be "unlearned" (referred to as extinction and habituation).

CBT for children with phobias is normally delivered over multiple sessions, but one-session treatment has been shown to be equally effective and is cheaper.[100][101]

Specialized forms of CBT

CBT-SP, an adaptation of CBT for suicide prevention (SP), was specifically designed for treating youths who are severely depressed and who have recently attempted suicide within the past 90 days, and was found to be effective, feasible, and acceptable.[102]

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a specialist branch of CBT (sometimes referred to as contextual CBT[103]). ACT uses mindfulness and acceptance interventions and has been found to have a greater longevity in therapeutic outcomes. In a study with anxiety, CBT and ACT improved similarly across all outcomes from pre- to post-treatment. However, during a 12-month follow-up, ACT proved to be more effective, showing that it is a highly viable lasting treatment model for anxiety disorders.[104]

Computerized CBT (CCBT) has been proven to be effective by randomized controlled and other trials in treating depression and anxiety disorders,[57][60][93][105][81][106] including children.[107] Some research has found similar effectiveness to an intervention of informational websites and weekly telephone calls.[108][109] CCBT was found to be equally effective as face-to-face CBT in adolescent anxiety.[110]

Combined with other treatments

Studies have provided evidence that when examining animals and humans, that glucocorticoids may lead to a more successful extinction learning during exposure therapy for anxiety disorders. For instance, glucocorticoids can prevent aversive learning episodes from being retrieved and heighten reinforcement of memory traces creating a non-fearful reaction in feared situations. A combination of glucocorticoids and exposure therapy may be a better-improved treatment for treating people with anxiety disorders.[111]

Prevention

For anxiety disorders, use of CBT with people at risk has significantly reduced the number of episodes of generalized anxiety disorder and other anxiety symptoms, and also given significant improvements in explanatory style, hopelessness, and dysfunctional attitudes.[81][112][113] In another study, 3% of the group receiving the CBT intervention developed generalized anxiety disorder by 12 months postintervention compared with 14% in the control group.[114] Individuals with subthreshold levels of panic disorder significantly benefitted from use of CBT.[115][116] Use of CBT was found to significantly reduce social anxiety prevalence.[117]

For depressive disorders, a stepped-care intervention (watchful waiting, CBT and medication if appropriate) achieved a 50% lower incidence rate in a patient group aged 75 or older.[118] Another depression study found a neutral effect compared to personal, social, and health education, and usual school provision, and included a comment on potential for increased depression scores from people who have received CBT due to greater self recognition and acknowledgement of existing symptoms of depression and negative thinking styles.[119] A further study also saw a neutral result.[120] A meta-study of the Coping with Depression course, a cognitive behavioral intervention delivered by a psychoeducational method, saw a 38% reduction in risk of major depression.[121]

Bipolar disorder

Many studies show CBT, combined with pharmacotherapy, is effective in improving depressive symptoms, mania severity and psychosocial functioning with mild to moderate effects, and that it is better than medication alone.[122][123][124]

INSERM's 2004 review found that CBT is an effective therapy for several mental disorders, including bipolar disorder.[61] This included schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress, anxiety disorders, bulimia, anorexia, personality disorders and alcohol dependency.[61]

Psychosis

In long-term psychoses, CBT is used to complement medication and is adapted to meet individual needs. Interventions particularly related to these conditions include exploring reality testing, changing delusions and hallucinations, examining factors which precipitate relapse, and managing relapses.[65] Meta-analyses confirm the effectiveness of metacognitive training (MCT) for the improvement of positive symptoms (e.g., delusions).[125][126]

For people at risk of psychosis, in 2014 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended preventive CBT.[127][128]

Schizophrenia

INSERM's 2004 review found that CBT is an effective therapy for several mental disorders, including schizophrenia.[61]

A Cochrane review reported CBT had "no effect on long‐term risk of relapse" and no additional effect above standard care.[129] A 2015 systematic review investigated the effects of CBT compared with other psychosocial therapies for people with schizophrenia and determined that there is no clear advantage over other, often less expensive, interventions but acknowledged that better quality evidence is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.[130]

Addiction and substance use disorders

Pathological and problem gambling

CBT is also used for pathological and problem gambling. The percentage of people who problem gamble is 1–3% around the world.[131] Cognitive behavioral therapy develops skills for relapse prevention and someone can learn to control their mind and manage high-risk cases.[132] There is evidence of efficacy of CBT for treating pathological and problem gambling at immediate follow up, however the longer term efficacy of CBT for it is currently unknown.[133]

Smoking cessation

CBT looks at the habit of smoking cigarettes as a learned behavior, which later evolves into a coping strategy to handle daily stressors. Since smoking is often easily accessible and quickly allows the user to feel good, it can take precedence over other coping strategies, and eventually work its way into everyday life during non-stressful events as well. CBT aims to target the function of the behavior, as it can vary between individuals, and works to inject other coping mechanisms in place of smoking. CBT also aims to support individuals with strong cravings, which are a major reported reason for relapse during treatment.[134]

In a 2008 controlled study out of Stanford University School of Medicine suggested CBT may be an effective tool to help maintain abstinence. The results of 304 random adult participants were tracked over the course of one year. During this program, some participants were provided medication, CBT, 24-hour phone support, or some combination of the three methods. At 20 weeks, the participants who received CBT had a 45% abstinence rate, versus non-CBT participants, who had a 29% abstinence rate. Overall, the study concluded that emphasizing cognitive and behavioral strategies to support smoking cessation can help individuals build tools for long term smoking abstinence.[135]

Mental health history can affect the outcomes of treatment. Individuals with a history of depressive disorders had a lower rate of success when using CBT alone to combat smoking addiction.[136]

A Cochrane review was unable to find evidence of any difference between CBT and hypnosis for smoking cessation. While this may be evidence of no effect, further research may uncover an effect of CBT for smoking cessation.[137]

Substance use disorders

Studies have shown CBT to be an effective treatment for substance use disorders.[67][138][139] For individuals with substance use disorders, CBT aims to reframe maladaptive thoughts, such as denial, minimizing and catastrophizing thought patterns, with healthier narratives.[140] Specific techniques include identifying potential triggers and developing coping mechanisms to manage high-risk situations. Research has shown CBT to be particularly effective when combined with other therapy-based treatments or medication.[141]

INSERM's 2004 review found that CBT is an effective therapy for several mental disorders, including alcohol dependency.[61]

Internet addiction

Research has identified Internet addiction as a new clinical disorder that causes relational, occupational, and social problems. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been suggested as the treatment of choice for Internet addiction, and addiction recovery in general has used CBT as part of treatment planning.[142] There is also evidence for the efficacy of CBT in multicenter randomized controlled trials such as STICA (Short-Term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction). [143]

Eating disorders

Though many forms of treatment can support individuals with eating disorders, CBT is proven to be a more effective treatment than medications and interpersonal psychotherapy alone.[62][8] CBT aims to combat major causes of distress such as negative cognitions surrounding body weight, shape and size. CBT therapists also work with individuals to regulate strong emotions and thoughts that lead to dangerous compensatory behaviors. CBT is the first line of treatment for bulimia nervosa, and Eating Disorder Non-Specific.[144] While there is evidence to support the efficacy of CBT for bulimia nervosa and binging, the evidence is somewhat variable and limited by small study sizes.[145] INSERM's 2004 review found that CBT is an effective therapy for several mental disorders, including bulimia and anorexia nervosa.[61]

With autistic adults

Emerging evidence for cognitive behavioral interventions aimed at reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in autistic adults without intellectual disability has been identified through a systematic review.[146] While the research was focused on adults, cognitive behavioral interventions have also been beneficial to autistic children.[147] A 2021 Cochrane review found limited evidence regarding the efficacy of CBT for obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder stating a need for further study.[148]

Dementia and mild cognitive impairment

A Cochrane review in 2022 found that adults with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who experience symptoms of depression may benefit from CBT, whereas other counselling or supportive interventions might not improve symptoms significantly.[149] Across 5 different psychometric scales, where higher scores indicate severity of depression, adults receiving CBT reported somewhat lower mood scores than those receiving usual care for dementia and MCI overall.[149] In this review, a sub-group analysis found clinically significant benefits only among those diagnosed with dementia, rather than MCI.[149][150]

The likelihood of remission from depression also appeared to be 84% higher following CBT, though the evidence for this was less certain. Anxiety, cognition and other neuropsychiatric symptoms were not significantly improved following CBT, however this review did find moderate evidence of improved quality of life and daily living activity scores in those with dementia and MCI.[149]

Post-traumatic stress

Cognitive behavioral therapy interventions may have some benefits for people who have post-traumatic stress related to surviving rape, sexual abuse, or sexual assault.[151]

Other uses

Evidence suggests a possible role for CBT in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),[152] hypochondriasis,[153] and bipolar disorder,[122] but more study is needed and results should be interpreted with caution. CBT has been studied as an aid in the treatment of anxiety associated with stuttering. Initial studies have shown CBT to be effective in reducing social anxiety in adults who stutter,[154] but not in reducing stuttering frequency.[155][156]

There is some evidence that CBT is superior in the long-term to benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepines in the treatment and management of insomnia.[157] Computerized CBT (CCBT) has been proven to be effective by randomized controlled and other trials in treating insomnia.[158] Some research has found similar effectiveness to an intervention of informational websites and weekly telephone calls.[108][109] CCBT was found to be equally effective as face-to-face CBT in insomnia.[158]

A Cochrane review of interventions aimed at preventing psychological stress in healthcare workers found that CBT was more effective than no intervention but no more effective than alternative stress-reduction interventions.[159]

Cochrane Reviews have found no convincing evidence that CBT training helps foster care providers manage difficult behaviors in the youths under their care,[160] nor was it helpful in treating people who abuse their intimate partners.[161]

CBT has been applied in both clinical and non-clinical environments to treat disorders such as personality disorders and behavioral problems.[162] INSERM's 2004 review found that CBT is an effective therapy for personality disorders.[61]

CBT has been used with other researchers as well to minimize chronic pain and help relieve symptoms from those suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). [163]

Individuals with medical conditions

In the case of people with metastatic breast cancer, data is limited but CBT and other psychosocial interventions might help with psychological outcomes and pain management.[164] A 2015 Cochrane review also found that CBT for symptomatic management of non-specific chest pain is probably effective in the short term. However, the findings were limited by small trials and the evidence was considered of questionable quality.[165] Cochrane reviews have found no evidence that CBT is effective for tinnitus, although there appears to be an effect on management of associated depression and quality of life in this condition.[166] CBT combined with hypnosis and distraction reduces self-reported pain in children.[167]

There is limited evidence to support CBT's use in managing the impact of multiple sclerosis,[168][169] sleep disturbances related to aging,[170] and dysmenorrhea,[171] but more study is needed and results should be interpreted with caution.

Previously CBT has been considered as moderately effective for treating chronic fatigue syndrome,[172] however a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop stated that in respect of improving treatment options for ME/CFS that the modest benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy should be studied as an adjunct to other methods.[173] The Centres for Disease Control advice on the treatment of ME/CFS[174] makes no reference to CBT while the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[175] states that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has sometimes been assumed to be a cure for ME/CFS, however, it should only be offered to support people who live with ME/CFS to manage their symptoms, improve their functioning and reduce the distress associated with having a chronic illness."

Age

CBT is used to help people of all ages, but the therapy should be adjusted based on the age of the patient with whom the therapist is dealing. Older individuals in particular have certain characteristics that need to be acknowledged and the therapy altered to account for these differences thanks to age.[176] Of the small number of studies examining CBT for the management of depression in older people, there is currently no strong support.[177]

Description

Mainstream cognitive behavioral therapy assumes that changing maladaptive thinking leads to change in behavior and affect,[68] but recent variants emphasize changes in one's relationship to maladaptive thinking rather than changes in thinking itself.[178]

Cognitive distortions

Therapists use CBT techniques to help people challenge their patterns and beliefs and replace errors in thinking, known as cognitive distortions with "more realistic and effective thoughts, thus decreasing emotional distress and self-defeating behavior".[68] Cognitive distortions can be either a pseudo-discrimination belief[clarification needed] or an overgeneralization of something.[179] CBT techniques may also be used to help individuals take a more open, mindful, and aware posture toward cognitive distortions so as to diminish their impact.[178]

Mainstream CBT helps individuals replace "maladaptive... coping skills, cognitions, emotions and behaviors with more adaptive ones",[63] by challenging an individual's way of thinking and the way that they react to certain habits or behaviors,[180] but there is still controversy about the degree to which these traditional cognitive elements account for the effects seen with CBT over and above the earlier behavioral elements such as exposure and skills training.[181]

Phases in therapy

CBT can be seen as having six phases:[63]

- Assessment or psychological assessment;

- Reconceptualization;

- Skills acquisition;

- Skills consolidation and application training;

- Generalization and maintenance;

- Post-treatment assessment follow-up.

These steps are based on a system created by Kanfer and Saslow.[182] After identifying the behaviors that need changing, whether they be in excess or deficit, and treatment has occurred, the psychologist must identify whether or not the intervention succeeded. For example, "If the goal was to decrease the behavior, then there should be a decrease relative to the baseline. If the critical behavior remains at or above the baseline, then the intervention has failed."[182]

The steps in the assessment phase include:

- Identify critical behaviors;

- Determine whether critical behaviors are excesses or deficits;

- Evaluate critical behaviors for frequency, duration, or intensity (obtain a baseline);

- If excess, attempt to decrease frequency, duration, or intensity of behaviors; if deficits, attempt to increase behaviors.[183]

The re-conceptualization phase makes up much of the "cognitive" portion of CBT.[63]

Delivery protocols

There are different protocols for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy, with important similarities among them.[184] Use of the term CBT may refer to different interventions, including "self-instructions (e.g. distraction, imagery, motivational self-talk), relaxation and/or biofeedback, development of adaptive coping strategies (e.g. minimizing negative or self-defeating thoughts), changing maladaptive beliefs about pain, and goal setting".[63] Treatment is sometimes manualized, with brief, direct, and time-limited treatments for individual psychological disorders that are specific technique-driven.[185] CBT is used in both individual and group settings, and the techniques are often adapted for self-help applications. Some clinicians and researchers are cognitively oriented (e.g. cognitive restructuring), while others are more behaviorally oriented (e.g. in vivo exposure therapy). Interventions such as imaginal exposure therapy combine both approaches.[186][187]

Related techniques

CBT may be delivered in conjunction with a variety of diverse but related techniques such as exposure therapy, stress inoculation, cognitive processing therapy, cognitive therapy, metacognitive therapy, metacognitive training, relaxation training, dialectical behavior therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy.[188][189] Some practitioners promote a form of mindful cognitive therapy which includes a greater emphasis on self-awareness as part of the therapeutic process.[190]

Methods of access

Therapist

A typical CBT program would consist of face-to-face sessions between patient and therapist, made up of 6–18 sessions of around an hour each with a gap of 1–3 weeks between sessions. This initial program might be followed by some booster sessions, for instance after one month and three months.[191] CBT has also been found to be effective if patient and therapist type in real time to each other over computer links.[192][193]

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is most closely allied with the scientist–practitioner model in which clinical practice and research are informed by a scientific perspective, clear operationalization of the problem, and an emphasis on measurement, including measuring changes in cognition and behavior and the attainment of goals. These are often met through "homework" assignments in which the patient and the therapist work together to craft an assignment to complete before the next session.[194] The completion of these assignments – which can be as simple as a person with depression attending some kind of social event – indicates a dedication to treatment compliance and a desire to change.[194] The therapists can then logically gauge the next step of treatment based on how thoroughly the patient completes the assignment.[194] Effective cognitive behavioral therapy is dependent on a therapeutic alliance between the healthcare practitioner and the person seeking assistance.[2][195] Unlike many other forms of psychotherapy, the patient is very involved in CBT.[194] For example, an anxious patient may be asked to talk to a stranger as a homework assignment, but if that is too difficult, he or she can work out an easier assignment first.[194] The therapist needs to be flexible and willing to listen to the patient rather than acting as an authority figure.[194]

Computerized or Internet-delivered (CCBT)

Computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (CCBT) has been described by NICE as a "generic term for delivering CBT via an interactive computer interface delivered by a personal computer, internet, or interactive voice response system",[196] instead of face-to-face with a human therapist. It is also known as internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy or ICBT.[197] CCBT has potential to improve access to evidence-based therapies, and to overcome the prohibitive costs and lack of availability sometimes associated with retaining a human therapist.[198][199] In this context, it is important not to confuse CBT with 'computer-based training', which nowadays is more commonly referred to as e-Learning.

Although improvements in both research quality and treatment adherence is required before advocating for the global dissemination of CCBT,[200] it has been found in meta-studies to be cost-effective and often cheaper than usual care,[201][202] including for anxiety[203] and PTSD.[204][205] Studies have shown that individuals with social anxiety and depression experienced improvement with online CBT-based methods.[206] A study assessing an online version of CBT for people with mild-to-moderate PTSD found that the online approach was as effective as, and cheaper than, the same therapy given face-to-face.[204][205] A review of current CCBT research in the treatment of OCD in children found this interface to hold great potential for future treatment of OCD in youths and adolescent populations.[207] Additionally, most internet interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder use CCBT. CCBT is also predisposed to treating mood disorders amongst non-heterosexual populations, who may avoid face-to-face therapy from fear of stigma. However presently CCBT programs seldom cater to these populations.[208]

In February 2006 NICE recommended that CCBT be made available for use within the NHS across England and Wales for patients presenting with mild-to-moderate depression, rather than immediately opting for antidepressant medication,[196] and CCBT is made available by some health systems.[209] The 2009 NICE guideline recognized that there are likely to be a number of computerized CBT products that are useful to patients, but removed endorsement of any specific product.[210]

Smartphone app-delivered

Another new method of access is the use of mobile app or smartphone applications to deliver self-help or guided CBT. Technology companies are developing mobile-based artificial intelligence chatbot applications in delivering CBT as an early intervention to support mental health, to build psychological resilience, and to promote emotional well-being. Artificial intelligence (AI) text-based conversational application delivered securely and privately over smartphone devices have the ability to scale globally and offer contextual and always-available support. Active research is underway including real-world data studies[211] that measure effectiveness and engagement of text-based smartphone chatbot apps for delivery of CBT using a text-based conversational interface. Recent market research and analysis of over 500 online mental healthcare solutions identified 3 key challenges in this market: quality of the content, guidance of the user and personalisation.[212]

A study compared CBT alone with a mindfulness-based therapy combined with CBT, both delivered via an app. It found that mindfulness-based self-help reduced the severity of depression more than CBT self-help in the short-term. Overall, NHS costs for the mindfulness approach were £500 less per person than for CBT.[213][214]

Reading self-help materials

Enabling patients to read self-help CBT guides has been shown to be effective by some studies.[215][216][217] However one study found a negative effect in patients who tended to ruminate,[218] and another meta-analysis found that the benefit was only significant when the self-help was guided (e.g. by a medical professional).[219]

Group educational course

Patient participation in group courses has been shown to be effective.[220] In a meta-analysis reviewing evidence-based treatment of OCD in children, individual CBT was found to be more efficacious than group CBT.[207]

Types

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy (BCBT) is a form of CBT which has been developed for situations in which there are time constraints on the therapy sessions and specifically for those struggling with suicidal ideation and/or making suicide attempts.[221] BCBT was based on Rudd's proposed "suicidal mode", an elaboration of Beck's modal theory.[222][223] BCBT takes place over a couple of sessions that can last up to 12 accumulated hours by design. This technique was first implemented and developed with soldiers on active duty by Dr. M. David Rudd to prevent suicide.[221]

Breakdown of treatment[221]

- Orientation

- Commitment to treatment

- Crisis response and safety planning

- Means restriction

- Survival kit

- Reasons for living card

- Model of suicidality

- Treatment journal

- Lessons learned

- Skill focus

- Skill development worksheets

- Coping cards

- Demonstration

- Practice

- Skill refinement

- Relapse prevention

- Skill generalization

- Skill refinement

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy (CEBT) is a form of CBT developed initially for individuals with eating disorders but now used with a range of problems including anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anger problems. It combines aspects of CBT and dialectical behavioral therapy and aims to improve understanding and tolerance of emotions in order to facilitate the therapeutic process. It is frequently used as a "pretreatment" to prepare and better equip individuals for longer-term therapy.[224]

Structured cognitive behavioral training

Structured cognitive-behavioral training (SCBT) is a cognitive-based process with core philosophies that draw heavily from CBT. Like CBT, SCBT asserts that behavior is inextricably related to beliefs, thoughts, and emotions. SCBT also builds on core CBT philosophy by incorporating other well-known modalities in the fields of behavioral health and psychology: most notably, Albert Ellis's rational emotive behavior therapy. SCBT differs from CBT in two distinct ways. First, SCBT is delivered in a highly regimented format. Second, SCBT is a predetermined and finite training process that becomes personalized by the input of the participant. SCBT is designed to bring a participant to a specific result in a specific period of time. SCBT has been used to challenge addictive behavior, particularly with substances such as tobacco,[225] alcohol and food, and to manage diabetes and subdue stress and anxiety. SCBT has also been used in the field of criminal psychology in the effort to reduce recidivism.

Moral reconation therapy

Moral reconation therapy, a type of CBT used to help felons overcome antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), slightly decreases the risk of further offending.[226] It is generally implemented in a group format because of the risk of offenders with ASPD being given one-on-one therapy reinforces narcissistic behavioral characteristics, and can be used in correctional or outpatient settings. Groups usually meet weekly for two to six months.[227]

Stress inoculation training

This type of therapy uses a blend of cognitive, behavioral, and certain humanistic training techniques to target the stressors of the client. This usually is used to help clients better cope with their stress or anxiety after stressful events.[228] This is a three-phase process that trains the client to use skills that they already have to better adapt to their current stressors. The first phase is an interview phase that includes psychological testing, client self-monitoring, and a variety of reading materials. This allows the therapist to individually tailor the training process to the client.[228] Clients learn how to categorize problems into emotion-focused or problem-focused so that they can better treat their negative situations. This phase ultimately prepares the client to eventually confront and reflect upon their current reactions to stressors, before looking at ways to change their reactions and emotions to their stressors. The focus is conceptualization.[228]

The second phase emphasizes the aspect of skills acquisition and rehearsal that continues from the earlier phase of conceptualization. The client is taught skills that help them cope with their stressors. These skills are then practised in the space of therapy. These skills involve self-regulation, problem-solving, interpersonal communication skills, etc.[228]

The third and final phase is the application and following through of the skills learned in the training process. This gives the client opportunities to apply their learned skills to a wide range of stressors. Activities include role-playing, imagery, modeling, etc. In the end, the client will have been trained on a preventive basis to inoculate personal, chronic, and future stressors by breaking down their stressors into problems they will address in long-term, short-term, and intermediate coping goals.[228]

Activity-guided CBT: Group-knitting

A newly developed group therapy model based on CBT integrates knitting into the therapeutical process and has been proven to yield reliable and promising results. The foundation for this novel approach to CBT is the frequently emphasized notion that therapy success depends on the embeddedness of the therapy method in the patients' natural routine. Similar to standard group-based CBT, patients meet once a week in a group of 10 to 15 patients and knit together under the instruction of a trained psychologist or mental health professional. Central for the therapy is the patient's imaginative ability to assign each part of the wool to a certain thought. During the therapy, the wool is carefully knitted, creating a knitted piece of any form. This therapeutical process teaches the patient to meaningfully align thought, by (physically) creating a coherent knitted piece. Moreover, since CBT emphasizes the behavior as a result of cognition, the knitting illustrates how thoughts (which are tried to be imaginary tight to the wool) materialize into the reality surrounding us.[229][230]

Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral hypnotherapy

Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral hypnotherapy (MCBH) is a form of CBT that focuses on awareness in a reflective approach, addressing subconscious tendencies. It is more the process that contains three phases for achieving wanted goals and integrates the principles of mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral techniques with the transformative potential of hypnotherapy.[231]

Unified Protocol

The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) is a form of CBT, developed by David H. Barlow and researchers at Boston University, that can be applied to a range of and anxiety disorders. The rationale is that anxiety and depression disorders often occur together due to common underlying causes and can efficiently be treated together.[232]

The UP includes a common set of components:[233]

- Psycho-education

- Cognitive reappraisal

- Emotion regulation

- Changing behaviour

The UP has been shown to produce equivalent results to single-diagnosis protocols for specific disorders, such as OCD and social anxiety disorder.[234] Several studies have shown that the UP is easier to disseminate as compared to single-diagnosis protocols.

Criticisms

Relative effectiveness

The research conducted for CBT has been a topic of sustained controversy. While some researchers write that CBT is more effective than other treatments,[94] many other researchers[23][235][21][95][236] and practitioners[237][238] have questioned the validity of such claims. For example, one study[94] determined CBT to be superior to other treatments in treating anxiety and depression. However, researchers[21] responding directly to that study conducted a re-analysis and found no evidence of CBT being superior to other bona fide treatments, and conducted an analysis of thirteen other CBT clinical trials and determined that they failed to provide evidence of CBT superiority. In cases where CBT has been reported to be statistically better than other psychological interventions in terms of primary outcome measures, effect sizes were small and suggested that those differences were clinically meaningless and insignificant. Moreover, on secondary outcomes (i.e., measures of general functioning) no significant differences have been typically found between CBT and other treatments.[21][239]

A major criticism has been that clinical studies of CBT efficacy (or any psychotherapy) are not double-blind (i.e., either the subjects or the therapists in psychotherapy studies are not blind to the type of treatment). They may be single-blinded, i.e. the rater may not know the treatment the patient received, but neither the patients nor the therapists are blinded to the type of therapy given (two out of three of the persons involved in the trial, i.e., all of the persons involved in the treatment, are unblinded). The patient is an active participant in correcting negative distorted thoughts, thus quite aware of the treatment group they are in.[240]

The importance of double-blinding was shown in a meta-analysis that examined the effectiveness of CBT when placebo control and blindness were factored in.[241] Pooled data from published trials of CBT in schizophrenia, major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar disorder that used controls for non-specific effects of intervention were analyzed. This study concluded that CBT is no better than non-specific control interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia and does not reduce relapse rates; treatment effects are small in treatment studies of MDD, and it is not an effective treatment strategy for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder. For MDD, the authors note that the pooled effect size was very low.[242][243][244]

Declining effectiveness

Additionally, a 2015 meta-analysis revealed that the positive effects of CBT on depression have been declining since 1977. The overall results showed two different declines in effect sizes: 1) an overall decline between 1977 and 2014, and 2) a steeper decline between 1995 and 2014. Additional sub-analysis revealed that CBT studies where therapists in the test group were instructed to adhere to the Beck CBT manual had a steeper decline in effect sizes since 1977 than studies where therapists in the test group were instructed to use CBT without a manual. The authors reported that they were unsure why the effects were declining but did list inadequate therapist training, failure to adhere to a manual, lack of therapist experience, and patients' hope and faith in its efficacy waning as potential reasons. The authors did mention that the current study was limited to depressive disorders only.[245]

High drop-out rates

Furthermore, other researchers write that CBT studies have high drop-out rates compared to other treatments. One meta-analysis found that CBT drop-out rates were 17% higher than those of other therapies.[95] This high drop-out rate is also evident in the treatment of several disorders, particularly the eating disorder anorexia nervosa, which is commonly treated with CBT. Those treated with CBT have a high chance of dropping out of therapy before completion and reverting to their anorexia behaviors.[246]

Other researchers analyzing treatments for youths who self-injure found similar drop-out rates in CBT and DBT groups. In this study, the researchers analyzed several clinical trials that measured the efficacy of CBT administered to youths who self-injure. The researchers concluded that none of them were found to be efficacious.[236]

Philosophical concerns with CBT methods

The methods employed in CBT research have not been the only criticisms; some individuals have called its theory and therapy into question.[247]

Slife and Williams write that one of the hidden assumptions in CBT is that of determinism, or the absence of free will. They argue that CBT holds that external stimuli from the environment enter the mind, causing different thoughts that cause emotional states: nowhere in CBT theory is agency, or free will, accounted for.[237]

Another criticism of CBT theory, especially as applied to major depressive disorder (MDD), is that it confounds the symptoms of the disorder with its causes.[240]

Side effects

CBT is generally regarded as having very few if any side effects.[248][249] Calls have been made by some for more appraisal of possible side effects of CBT.[250] Many randomized trials of psychological interventions like CBT do not monitor potential harms to the patient.[251] In contrast, randomized trials of pharmacological interventions are much more likely to take adverse effects into consideration.[252]

A 2017 meta-analysis revealed that adverse events are not common in children receiving CBT and, furthermore, that CBT is associated with fewer dropouts than either placebo or medications.[253] Nevertheless, CBT therapists do sometimes report 'unwanted events' and side effects in their outpatients with "negative wellbeing/distress" being the most frequent.[254]

Socio-political concerns

The writer and group analyst Farhad Dalal questions the socio-political assumptions behind the introduction of CBT. According to one reviewer, Dalal connects the rise of CBT with "the parallel rise of neoliberalism, with its focus on marketization, efficiency, quantification and managerialism", and he questions the scientific basis of CBT, suggesting that "the 'science' of psychological treatment is often less a scientific than a political contest".[255] In his book, Dalal also questions the ethical basis of CBT.[256]

Society and culture

The UK's National Health Service announced in 2008 that more therapists would be trained to provide CBT at government expense[257] as part of an initiative called Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT).[258] The NICE said that CBT would become the mainstay of treatment for non-severe depression, with medication used only in cases where CBT had failed.[257] Therapists complained that the data does not fully support the attention and funding CBT receives. Psychotherapist and professor Andrew Samuels stated that this constitutes "a coup, a power play by a community that has suddenly found itself on the brink of corralling an enormous amount of money ... Everyone has been seduced by CBT's apparent cheapness."[257][259]

The UK Council for Psychotherapy issued a press release in 2012 saying that the IAPT's policies were undermining traditional psychotherapy and criticized proposals that would limit some approved therapies to CBT,[260] claiming that they restricted patients to "a watered down version of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), often delivered by very lightly trained staff".[260]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.), New York: The Guilford Press, 2011, pp. 19–20

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The New ABCs: A Practitioner's Guide to Neuroscience-Informed Cognitive-Behavior Therapy", Journal of Mental Health Counseling 37 (3): 206–20, 2015, doi:10.17744/1040-2861-37.3.206, http://www.n-cbt.com/uploads/7/8/1/8/7818585/n-cbt_researchpacket_newabcsmanuscript_advancecopy.pdf, retrieved 6 July 2016

- ↑ Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Abuse. https://discoverypointretreat.com/programs/individualized-recovery-plan/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-cbt/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "History of cognitive-behavioral therapy in youth", Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 179–189, 2011, doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.011, PMID 21440849

- ↑ "Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychiatry Research 225 (3): 236–246. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.058. PMID 25613661. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/efficacy-of-cognitivebehavioral-therapy-for-obsessivecompulsive-disorder(a4cc99db-c558-472b-ab4a-548bd9c08f29).html.

- ↑ "Comparison of psychological placebo and waiting list control conditions in the assessment of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis". Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry 26 (6): 319–331. December 2014. doi:10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.214173. PMID 25642106.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Eating Disorders". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 17 (1): 417–438. May 2021. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-110907. PMID 33962536.

- ↑ "Searching for a better treatment for eating disorders" (in en). Knowable Magazine. 16 December 2021. doi:10.1146/knowable-121621-1. https://knowablemagazine.org/article/mind/2021/searching-better-treatment-eating-disorders. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ ((APA Div. 12 (Society of Clinical Psychology))) (2017). "What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?". American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral.

- ↑ "Current status of cognitive behavioral therapy for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 497–509. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.001. PMID 20599129.

- ↑ "Internet-based psychological treatments for depression". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 12 (7): 861–869; quiz 870. July 2012. doi:10.1586/ern.12.63. PMID 22853793.

- ↑ "Why Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Is the Current Gold Standard of Psychotherapy". Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 4. 29 January 2018. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004. PMID 29434552.

- ↑ "The science of cognitive therapy". Behavior Therapy 44 (2): 199–212. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.007. PMID 23611069.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Psychology (2nd ed.), New York: Worth Pub, 2010, p. 600

- ↑ "Theoretical foundations of cognitive-behavior therapy for anxiety and depression". Annual Review of Psychology 47: 33–57. 1996. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.33. PMID 8624137.

- ↑ "Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for major depressive disorder: review of systematic reviews". BMJ Open 7 (6): e014912. June 2017. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014912. PMID 28615268.

- ↑ "A meta-analysis of behavior therapy for Tourette Syndrome". Journal of Psychiatric Research 50: 106–112. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.009. PMID 24398255.

- ↑ "A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: rationale for trial, method, and description of sample". Journal of Personality Disorders 20 (5): 431–449. October 2006. doi:10.1521/pedi.2006.20.5.431. PMID 17032157.

- ↑ "Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial". JAMA 292 (7): 807–820. August 2004. doi:10.1001/jama.292.7.807. PMID 15315995.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus other therapies: redux". Clinical Psychology Review 33 (3): 395–405. April 2013. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.004. PMID 23416876.

- ↑ "The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy". The American Psychologist 65 (2): 98–109. 2010. doi:10.1037/a0018378. PMID 20141265. http://efpp.org/texts/shedler.pdf. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine 10 (5): e1001454. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454. PMID 23723742.

- ↑ "Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 54 (5): 283–291. May 2009. doi:10.1177/070674370905400502. PMID 19497160.

- ↑ "Healing in the History of Christianity". Oxford University Press. 2005. https://academic.oup.com/book/6310/chapter/149988133.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in Orthodox Jews". Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 3 (2): 271–288. December 1996. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(96)80018-6. ISSN 1077-7229.

- ↑ "Chinese Taoist Cognitive Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Contemporary China" (in en). Transcultural Psychiatry 39 (1): 115–129. March 2002. doi:10.1177/136346150203900105. ISSN 1363-4615. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/136346150203900105.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy of religious and nonreligious cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of clinical depression in religious individuals". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60 (1): 94–103. February 1992. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.60.1.94. PMID 1556292.

- ↑ "The Comparative Efficacy of Christian and Secular Rational-Emotive Therapy with Christian Clients" (in en). Journal of Psychology and Theology 22 (2): 130–140. June 1994. doi:10.1177/009164719402200206. ISSN 0091-6471.

- ↑ "A Comparison of Secular and Religious Versions of Cognitive Therapy with Depressed Christian College Students" (in en). Journal of Psychology and Theology 12 (1): 45–54. March 1984. doi:10.1177/009164718401200106. ISSN 0091-6471. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/009164718401200106.

- ↑ "Secular versus Christian Inpatient Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Programs: Impact on Depression and Spiritual Well-Being" (in en). Journal of Psychology and Theology 27 (4): 309–318. December 1999. doi:10.1177/009164719902700403. ISSN 0091-6471. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/009164719902700403.

- ↑ "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 357–377. 2004. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z. ISSN 0022-4197. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27512819.

- ↑ The compassionate mind: a new approach to life's challanges (1st ed.). London: Constable. 2009. ISBN 978-1-84529-713-8.

- ↑ Donald Robertson (2010). The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. London: Karnac. p. xix. ISBN 978-1-85575-756-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=XsOFyJaR5vEC&pg=PR19.

- ↑ Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. 1979. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-89862-000-9.

- ↑ Personality theories (7th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. p. 424.

- ↑ "Mill and mental phenomena: critical contributions to a science of cognition". Behavioral Sciences 3 (2): 217–231. June 2013. doi:10.3390/bs3020217. PMID 25379235.

- ↑ An intellectual history of psychology (3rd ed.). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. 1995. https://archive.org/details/intellectualhist00robeho.

- ↑ 39.00 39.01 39.02 39.03 39.04 39.05 39.06 39.07 39.08 39.09 39.10 Clinical psychology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. 2007.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 "The evolution of cognitive behaviour therapy". Science and practice of cognitive behaviour therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1997. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-19-262726-1.

- ↑ "The Elimination of Children's Fears". Journal of Experimental Psychology 7 (5): 382–390. 1924. doi:10.1037/h0072283.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Current psychotherapies (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. 2008.

- ↑ "The effects of psychotherapy: an evaluation". Journal of Consulting Psychology 16 (5): 319–324. October 1952. doi:10.1037/h0063633. PMID 13000035.

- ↑ "Desperately Seeking Hope and Help for Your Nerves? Try Reading 'Hope and Help for Your Nerves'". The New York Times. New York Times. 26 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/books/hope-help-for-your-nerves-claire-weekes-virus.html.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 "Behavior therapy". Current psychotherapies (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. 2008. pp. 63–106.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Adlerian psychotherapy". Current psychotherapies (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. 2008. pp. 63–106.

- ↑ "The truth is indeed sobering A Response to Dr. Lance Dodes (Part Two) > Detroit Legal News". https://legalnews.com/detroit/1403173.

- ↑ "The truth is indeed sobering A Response to Dr. Lance Dodes (Part Two)". Detroit Legal News. http://legalnews.com/detroit/1403173.

- ↑ "Rational emotive behavior therapy". Current psychotherapies (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. 2008. pp. 63–106.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 (in en) Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Third Edition: Basics and Beyond. Guilford Press. 2021. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-60918-506-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=J_iAUcHc60cC.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Emotions: A brief history. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. 2004. p. 53.

- ↑ "Profiles in History of Neuroscience and Psychiatry". The Medical Basis of Psychiatry. New York: Springer. 2016. pp. 925–1007. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2528-5_42. ISBN 978-1-4939-2527-8.

- ↑ Behavior therapy: Concepts, procedures, and applications (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. 1997.

- ↑ "The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care". World Psychiatry 16 (3): 245–246. October 2017. doi:10.1002/wps.20442. PMID 28941087.

- ↑ "'Third wave' cognitive and behavioural therapies versus other psychological therapies for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008704. October 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008704.pub2. PMID 24142844.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral therapy in anxiety disorders: current state of the evidence". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 13 (4): 413–421. 2011. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/cotte. PMID 22275847.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance". PLOS ONE 5 (6): e10942. June 2010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010942. PMID 20532167. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...510942R.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clinical Psychology Review 48: 43–51. August 2016. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.007. PMID 27393916. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/cognitivebehavioral-therapy-for-body-dysmorphic-disorder-a-systematic-review-and-metaanalysis-of-randomized-controlled-trials(0fe73d16-d299-4d3a-a96b-68254931ac92).html.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Cognitive behavioral therapy for mood disorders: efficacy, moderators and mediators". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 537–555. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.005. PMID 20599132.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Meta-review of the effectiveness of computerised CBT in treating depression". BMC Psychiatry 11 (1): 131. August 2011. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-131. PMID 21838902.

- ↑ 61.00 61.01 61.02 61.03 61.04 61.05 61.06 61.07 61.08 61.09 61.10 61.11 61.12 61.13 INSERM Collective Expertise Centre (2000). Psychotherapy: Three approaches evaluated (Report). Paris, France: Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale. NCBI bookshelf NBK7123. PMID 21348158. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7123/.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 611–627. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004. PMID 20599136.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 "Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with cognitive behavioral therapy". The Spine Journal 8 (1): 40–44. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.007. PMID 18164452.

- ↑ "The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for personality disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 657–685. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.007. PMID 20599139.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic psychosis". Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 37 (2): 106–114. 2009. PMID 19401859. http://www.actaspsiquiatria.es/repositorio//10/56/ENG/10-56-ENG-106-114-498857.pdf.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 527–536. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.009. PMID 20599131.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 "Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 33 (3): 511–525. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012. PMID 20599130.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 "Nonpharmacologic treatment for fibromyalgia: patient education, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, and complementary and alternative medicine". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 35 (2): 393–407. May 2009. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.003. PMID 19647150.

- ↑ "An evidence-based review of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosocial issues post-spinal cord injury". Rehabilitation Psychology 56 (1): 15–25. February 2011. doi:10.1037/a0022743. PMID 21401282.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 217–238. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.003. PMID 21440852.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with body dysmorphic disorder: current status and future directions". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 287–304. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.004. PMID 21440856.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression and suicidality". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 191–204. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.012. PMID 21440850.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for weight management and eating disorders in children and adolescents". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 271–285. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.002. PMID 21440855.

- ↑ "A review of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 13 (4): 401–411. 2011. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/bboileau. PMID 22275846.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: a review and meta-analysis". Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 42 (3): 405–413. September 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.002. PMID 21458405.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood repetitive behavior disorders: tic disorders and trichotillomania". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20 (2): 319–328. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.007. PMID 21440858.

- ↑ Cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: A casebook for clinical practice (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. 2003. ISBN 978-1-57230-853-4. OCLC 50694773.

- ↑ "Interventions to support people exposed to adverse childhood experiences: systematic review of systematic reviews". BMC Public Health 20 (1): 657. May 2020. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08789-0. PMID 32397975.

- ↑ "UKCP response to Andy Burnham's speech on mental health" (Press release). UK Council for Psychotherapy. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ "Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Proven Effectiveness". Psychology Today. 23 November 2011. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/anxiety-files/201111/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-proven-effectiveness.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 "Computer-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy: effective and getting ready for dissemination". F1000 Medicine Reports 2: 49. July 2010. doi:10.3410/M2-49. PMID 20948835.

- ↑ "Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy: a meta-analysis". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63 (2): 214–220. April 1995. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.214. PMID 7751482.

- ↑ "Cognitive hypnotherapy for depression: an empirical investigation". The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 55 (2): 147–166. April 2007. doi:10.1080/00207140601177897. PMID 17365072.

- ↑ "Cognitive hypnotherapy for pain management". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 54 (4): 294–310. April 2012. doi:10.1080/00029157.2011.654284. PMID 22655332.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of common mental health problems". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. April 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/media/878/f7/cbtcommissioningguide.pdf.

- ↑ "Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2nd Edition". APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Comprehensive Guidelines and Guideline Watches. 1. 2006. ISBN 978-0-89042-336-3. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar-watch.pdf.

- ↑ "Comparative effects of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in depression: a meta-analytic approach". Clinical Psychology Review 21 (3): 401–419. April 2001. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00057-4. PMID 11288607.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 69 (4): 621–632. April 2008. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0415. PMID 18363421.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11 (11): CD013162. November 2020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013162.pub2. PMID 33196111.

- ↑ Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review Update (Report). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 17 May 2018. doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer207. PMID 30204376.

- ↑ "Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 52 (8): 853–860. August 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x. PMID 21155776.

- ↑ "Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (10): CD012371. October 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012371. PMID 27726123.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy in primary health care: a review". Family Practice 28 (5): 489–504. October 2011. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr017. PMID 21555339.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 "Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A meta-analytic review". Clinical Psychology Review 30 (6): 710–720. August 2010. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.003. PMID 20547435.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 "Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76 (6): 909–922. December 2008. doi:10.1037/a0013075. PMID 19045960.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Abnormal psychology (8th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. 2001. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-471-31811-8. https://archive.org/details/abnormalpsycholo00gera/page/247.

- ↑ American Psychological Association | Division 12. "What is Exposure Therapy?". https://www.div12.org/sites/default/files/WhatIsExposureTherapy.pdf.

- ↑ "Definition of In Vivo Exposure". Ptsd.about.com. 9 June 2014. http://ptsd.about.com/od/glossary/g/invivo.htm.

- ↑ Mowrer OH (1960). Learning theory and behavior. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-88275-127-6.[page needed]

- ↑ "One-session treatment is as effective as multi-session therapy for young people with phobias". NIHR Evidence. April 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_57627. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/alert/one-session-cbt-treatment-effective-for-young-people-with-phobias/.

- ↑ "One-session treatment compared with multisession CBT in children aged 7-16 years with specific phobias: the ASPECT non-inferiority RCT" (in EN). Health Technology Assessment 26 (42): 1–174. October 2022. doi:10.3310/IBCT0609. PMID 36318050.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48 (10): 1005–1013. October 2009. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e3181b5dbfe. PMID 19730273.