Medicine:Irritable bowel syndrome

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Spastic colon, nervous colon, mucous colitis, spastic bowel[1] |

| |

| 3d depiction of the pain of IBS | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain[1] |

| Usual onset | Before 45 years old[1] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, exclusion of other diseases[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Celiac disease, giardiasis, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, microscopic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, small intestine bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption, colon cancer[3][4] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic (dietary changes, medication, human milk oligosaccharides, probiotics, counseling)[5] |

| Prognosis | Normal life expectancy[6] |

| Frequency | 10–15% (developed world)[1][7] and 15–45% (globally)[8] |

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a "disorder of gut-brain interaction" characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and changes in the consistency of bowel movements.[1] These symptoms may occur over a long time, sometimes for years.[2] IBS can negatively affect quality of life and may result in missed school or work or reduced productivity at work.[9] Disorders such as anxiety, major depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome are common among people with IBS.[1][10][note 1] [11]

The causes of IBS may well be multi-factorial.[2] Theories include combinations of "gut–brain axis" problems, alterations in gut motility, visceral hypersensitivity, infections including small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, neurotransmitters, genetic factors, and food sensitivity.[2] Onset may be triggered by an intestinal infection[12] ("post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome") or a stressful life event.[13]

Diagnosis is based on symptoms in the absence of worrisome features and once other potential conditions have been ruled out.[3] Worrisome or "alarm" features include onset at greater than 50 years of age, weight loss, blood in the stool, or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease.[3] Other conditions that may present similarly include celiac disease, microscopic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, bile acid malabsorption, and colon cancer.[3]

Treatment of IBS is carried out to improve symptoms and can be very effective. This may include dietary changes, medication, probiotics, and counseling.[5][14] Dietary measures include increasing soluble fiber intake, or a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). The "low FODMAP" diet is meant for short to medium term use and is not intended as a life-long therapy.[3][15][16] The medication loperamide may be used to help with diarrhea while laxatives may be used to help with constipation.[3] There is strong clinical-trial evidence for the use of antidepressants, often in lower doses than that used for depression or anxiety, even in patients without comorbid mood disorder. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline and medications from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) group may improve overall symptoms and reduce pain.[3] Patient education and a good doctor–patient relationship are an important part of care.[3][17]

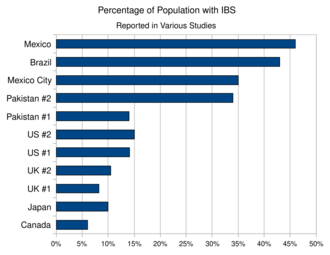

About 10–15% of people in the developed world are believed to be affected by IBS.[1][7] The prevalence varies according to country (from 1.1% to 45.0%) and criteria used to define IBS; however pooling the results of multiple studies gives an estimate of 11.2%.[8] It is more common in South America and less common in Southeast Asia.[3] In the Western world, it is twice as common in women as men and typically occurs before age 45.[1] However, women in East Asia are not more likely than their male counterparts to have IBS, indicating much lower rates among East Asian women.[18] There is likewise evidence that men from South America, South Asia and Africa are just as likely to have IBS as women in those regions, if not more so.[19] The condition appears to become less common with age.[3] IBS does not affect life expectancy or lead to other serious diseases.[6] The first description of the condition was in 1820, while the current term irritable bowel syndrome came into use in 1944.[20]

Classification

IBS can be classified as diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), constipation-predominant (IBS-C), with mixed/alternating stool pattern (IBS-M/IBS-A) or pain-predominant.[21] In some individuals, IBS may have an acute onset and develop after an infectious illness characterized by two or more of: fever, vomiting, diarrhea, or positive stool culture. This post-infective syndrome has consequently been termed "post-infectious IBS" (IBS-PI).[22][23][24][25]

Signs and symptoms

The primary symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain or discomfort in association with frequent diarrhea or constipation and a change in bowel habits.[26] Symptoms usually are experienced as acute attacks that subside within one day, but recurrent attacks are likely.[27] There may also be urgency for bowel movements, a feeling of incomplete evacuation (tenesmus) or bloating.[28] In some cases, the symptoms are relieved by bowel movements.[17] People with IBS, more commonly than others, have gastroesophageal reflux, symptoms relating to the genitourinary system, fibromyalgia, headache, backache, and psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety.[10][28] About a third of adults who have IBS also report sexual dysfunction, typically in the form of a reduction in libido.[29]

Cause

While the causes of IBS are still unknown, it is believed that the entire gut–brain axis is affected.[30][31] Recent findings suggest that an allergy triggered peripheral immune mechanism may underlie the symptoms associated with abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.[32] IBS is more prevalent in obese patients.[33]

Risk factors

The risk of developing IBS increases six-fold after acute gastrointestinal infection.[34] Post-infection,[34] further risk factors are young age, prolonged fever, anxiety, and depression.[35] Psychological factors, such as depression or anxiety, have not been shown to cause or influence the onset of IBS, but may play a role in the persistence and perceived severity of symptoms.[36] Nevertheless, they may worsen IBS symptoms and quality of life.[36] Antibiotic use also appears to increase the risk of developing IBS.[37] Research has found that genetic defects in innate immunity and epithelial homeostasis increase the risk of developing both post-infectious as well as other forms of IBS.[38]

Stress

Publications suggesting the role of the brain–gut axis appeared in the 1990s[39] and childhood physical and psychological abuse is often associated with the development of IBS.[40] It is believed that psychological stress may trigger IBS in predisposed individuals.[41]

Given the high levels of anxiety experienced by people with IBS and the overlap with conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, a potential explanation for IBS involves a disruption of the stress system. The stress response in the body involves the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) and the sympathetic nervous system, both of which have been shown to operate abnormally in people with IBS. Psychiatric illness or anxiety precedes IBS symptoms in two-thirds of people with IBS, and psychological traits predispose previously healthy people to developing IBS after gastroenteritis.[42][43]

Post-infectious

Approximately 10 percent of IBS cases are triggered by an acute gastroenteritis infection.[44] The CdtB toxin is produced by bacteria causing gastroenteritis and the host may develop an autoimmunity when host antibodies to CdtB cross-react with vinculin.[45] Genetic defects relating to the innate immune system and epithelial barrier as well as high stress and anxiety levels appear to increase the risk of developing post-infectious IBS. Post-infectious IBS usually manifests itself as the diarrhea-predominant subtype. Evidence has demonstrated that the release of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines during acute enteric infection causes increased gut permeability leading to translocation of the commensal bacteria across the epithelial barrier; this in turn can result in significant damage to local tissues, which can develop into chronic gut abnormalities in sensitive individuals. However, increased gut permeability is strongly associated with IBS regardless of whether IBS was initiated by an infection or not.[38] A link between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and tropical sprue has been proposed to be involved as a cause of post-infectious IBS.[46]

Bacteria

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) occurs with greater frequency in people who have been diagnosed with IBS compared to healthy controls.[47] SIBO is most common in diarrhea-predominate IBS but also occurs in constipation-predominant IBS more frequently than healthy controls. Symptoms of SIBO include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation among others. IBS may be the result of the immune system interacting abnormally with gut microbiota resulting in an abnormal cytokine signalling profile.[48]

Certain bacteria are found in lower or higher abundance when compared with healthy individuals. Generally Bacteroidota, Bacillota, and Pseudomonadota are increased and Actinomycetota, Bifidobacteria, and Lactobacillus are decreased. Within the human gut, there are common phyla found. The most common is Bacillota. This includes Lactobacillus, which is found to have a decrease in people with IBS, and Streptococcus, which is shown to have an increase in abundance. Within this phylum, species in the class Clostridia are shown to have an increase, specifically Ruminococcus and Dorea. The family Lachnospiraceae presents an increase in IBS-D patients. The second most common phylum is Bacteroidota. In people with IBS, the Bacteroidota phylum has been shown to have an overall decrease, but an increase in the genus Bacteroides. IBS-D shows a decrease for the phylum Actinomycetota and an increase in Pseudomonadota, specifically in the family Enterobacteriaceae.[49]

Fungus

There is growing evidence that alterations of gut microbiota (dysbiosis) are associated with the intestinal manifestations of IBS, but also with the psychiatric morbidity that coexists in up to 80% of people with IBS.[50] The role of the gut mycobiota, and especially of the abnormal proliferation of the yeast Candida albicans in some people with IBS, was under investigation as of 2005.[51]

Protozoa

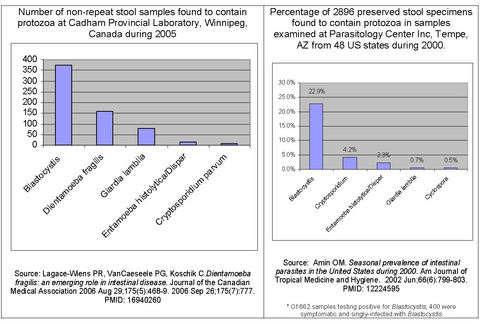

Protozoal infections can cause symptoms that mirror specific IBS subtypes,[54] e.g., infection by certain substypes of Blastocystis hominis (blastocystosis).[55][56] Many people regard these organisms as incidental findings, and unrelated to symptoms of IBS.

As of 2017, evidence indicates that blastocystis colonisation occurs more commonly in IBS affected individuals and is a possible risk factor for developing IBS.[57] Dientamoeba fragilis has also been considered a possible organism to study, though it is also found in people without IBS.[58]

Vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency is more common in individuals affected by irritable bowel syndrome.[59][60] Vitamin D is involved in regulating triggers for IBS including the gut microbiome, inflammatory processes and immune responses, as well as psychosocial factors.[61]

Genetics

SCN5A mutations are found in a small number of people who have IBS, particularly the constipation-predominant variant (IBS-C).[62][63] The resulting defect leads to disruption in bowel function, by affecting the Nav1.5 channel, in smooth muscle of the colon and pacemaker cells.[citation needed]

Mechanism

Genetic, environmental, and psychological factors seem to be important in the development of IBS. Studies have shown that IBS has a genetic component even though there is a predominant influence of environmental factors.[64]

Dysregulated brain-gut axis, abnormal serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) metabolism, and high density of mucosal nerve fibers in the intestines have been implicated in the mechanisms of IBS. A number of 5-HT receptor subtypes were involved in the IBS symptoms, including 5-HT3, 5-HT4, and 5-HT7 receptors. High levels of 5-HT7 receptor-expressing mucosal nerve fibers were observed in the colon of IBS patients. A role of 5-HT7 receptor in intestinal hyperalgesia was demonstrated in mouse models with visceral hypersensitivity, of which a novel 5-HT7 receptor antagonist administered by mouth reduced intestinal pain levels.[65]

There is evidence that abnormalities occur in the gut flora of individuals who have IBS, such as reduced diversity, a decrease in bacteria belonging to the phylum Bacteroidota, and an increase in those belonging to the phylum Bacillota.[50] The changes in gut flora are most profound in individuals who have diarrhoea-predominant IBS. Antibodies against common components (namely flagellin) of the commensal gut flora are a common occurrence in IBS affected individuals.[66]

Chronic low-grade inflammation commonly occurs in IBS affected individuals with abnormalities found including increased enterochromaffin cells, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and mast cells resulting in chronic immune-mediated inflammation of the gut mucosa.[30][67] IBS has been reported in greater quantities in multigenerational families with IBS than in the regular population.[68] It is believed that psychological stress can induce increased inflammation and thereby cause IBS to develop in predisposed individuals.[41]

Diagnosis

No specific laboratory or imaging tests can diagnose irritable bowel syndrome. Diagnosis should be based on symptoms, the exclusion of worrisome features, and the performance of specific investigations to rule out organic diseases that may present similar symptoms.[3][69]

The recommendations for physicians are to minimize the use of medical investigations.[70] The Rome criteria (see below) are usually used. They allow the diagnosis to be based only on symptoms, but no criteria based solely on symptoms is sufficiently accurate to diagnose IBS.[71][72] Worrisome features include onset at greater than 50 years of age, weight loss, blood in the stool, iron-deficiency anemia, or a family history of colon cancer, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease.[3] The criteria for selecting tests and investigations also depends on the level of available medical resources.[36]

Rome criteria

The Rome criteria are consensus guidelines, initially released in 1994 and updated periodically since then. These may pertain more closely to clinical trials as in practice, patient symptoms may vary considerably. The Rome IV criteria (2016) for IBS include recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least one day/week in the last three months, associated with additional stool- or defecation-related criteria.[73]

The algorithm may include additional tests to guard against misdiagnosis of other diseases as IBS. Such "red flag" symptoms may include weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, or nocturnal symptoms[vague]. However, red flag conditions may not always contribute to accuracy in diagnosis; for instance, as many as 31% of people with IBS have blood in their stool, many possibly from hemorrhoidal bleeding.[74]

The diagnostic algorithm identifies a name that can be applied to the person's condition based on the combination of symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, and constipation. For example, the statement "50% of returning travellers had developed functional diarrhea while 25% had developed IBS" would mean half the travellers had diarrhea while a quarter had diarrhea with abdominal pain. While some researchers believe this categorization system will help physicians understand IBS, others have questioned the value of the system and suggested all people with IBS have the same underlying disease but with different symptoms.[75]

Differential diagnosis

Colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, thyroid disorders (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism), and giardiasis can all feature abnormal defecation and abdominal pain. Less common causes of this symptom profile are carcinoid syndrome, microscopic colitis, bacterial overgrowth, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis; IBS is, however, a common presentation, and testing for these conditions would yield low numbers of positive results, so it is considered difficult to justify the expense.[76] Conditions that may present similarly include celiac disease, bile acid malabsorption, colon cancer, and dyssynergic defecation.[3]

Ruling out parasitic infections, lactose intolerance, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and celiac disease is recommended before a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is made.[69] An upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsies is necessary to identify the presence of celiac disease.[77] An ileocolonoscopy with biopsies is useful to exclude Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (Inflammatory bowel disease).[77]

Some people, managed for years for IBS, may have non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS).[4] Gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS are clinically indistinguishable from those of NCGS, but the presence of any of the following non-intestinal manifestations suggest a possible NCGS: headache or migraine, "foggy mind", chronic fatigue,[78] fibromyalgia,[79][80][81] joint and muscle pain,[78][79][82] leg or arm numbness,[78][79][82] tingling of the extremities,[78][82] dermatitis (eczema or skin rash),[78][82] atopic disorders,[78] allergy to one or more inhalants, foods or metals[78][79] (such as mites, graminaceae, parietaria, cat or dog hair/dander, shellfish, or nickel[79]), depression,[78][79][82] anxiety,[79] anemia,[78][82] iron-deficiency anemia, folate deficiency, asthma, rhinitis, eating disorders,[79] neuropsychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia,[82][83] autism,[79][82][83] peripheral neuropathy,[82][83] ataxia,[83] attention deficit hyperactivity disorder[78]) or autoimmune diseases.[78] An improvement with a gluten-free diet of immune-mediated symptoms, including autoimmune diseases, once having reasonably ruled out celiac disease and wheat allergy, is another way to realize a differential diagnosis.[78]

Investigations

Investigations are performed to exclude other conditions:[citation needed]

- Stool microscopy and culture (to exclude infectious conditions)

- Blood tests: Full blood examination, liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serological testing for coeliac disease

- Abdominal ultrasound (to exclude gallstones and other biliary tract diseases)

- Endoscopy and biopsies (to exclude peptic ulcer disease, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancies)

- Hydrogen breath testing (to exclude fructose and lactose malabsorption)

Misdiagnosis

People with IBS are at increased risk of being given inappropriate surgeries such as appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy due to being misdiagnosed as other medical conditions.[84] Some common examples of misdiagnosis include infectious diseases, coeliac disease,[85] Helicobacter pylori,[86][87] parasites (non-protozoal).[54][88][89] The American College of Gastroenterology recommends all people with symptoms of IBS be tested for coeliac disease.[90]

Bile acid malabsorption is also sometimes missed in people with diarrhea-predominant IBS. SeHCAT tests suggest around 30% of people with D-IBS have this condition, and most respond to bile acid sequestrants.[91]

Comorbidities

Several medical conditions, or comorbidities, appear with greater frequency in people with IBS.

- Neurological/psychiatric: A study of 97,593 individuals with IBS identified comorbidities such as headache, fibromyalgia, and depression.[92] IBS occurs in 51% of people with chronic fatigue syndrome and 49% of people with fibromyalgia, and psychiatric disorders occur in 94% of people with IBS.[10][note 1]

- Channelopathy and muscular dystrophy: IBS and functional GI diseases are comorbidities of genetic channelopathies that cause cardiac conduction defects and neuromuscular dysfunction, and result also in alterations in GI motility, secretion, and sensation.[93] Similarly, IBS and FBD are highly prevalent in myotonic muscle dystrophies. Digestive symptoms may be the first sign of dystrophic disease and may precede the musculo-skeletal features by up to 10 years.[94]

- Inflammatory bowel disease: IBS may be marginally associated with inflammatory bowel disease.[95] Researchers have found some correlation between IBS and IBD,[96] noting that people with IBD experience IBS-like symptoms when their IBD is in remission.[97][98] A three-year study found that patients diagnosed with IBS were 16.3 times more likely to be diagnosed with IBD during the study period, although this is likely due to an initial misdiagnosis.[99]

- Abdominal surgery: People with IBS were at increased risk of having unnecessary gall bladder removal surgery not due to an increased risk of gallstones, but rather to abdominal pain, awareness of having gallstones, and inappropriate surgical indications.[100] These people also are 87% more likely to undergo abdominal and pelvic surgery and three times more likely to undergo gallbladder surgery.[101] Also, people with IBS were twice as likely to undergo hysterectomy.[102]

- Endometriosis: One study reported a statistically significant link between migraine headaches, IBS, and endometriosis.[103]

- Other chronic disorders: Interstitial cystitis may be associated with other chronic pain syndromes, such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. The connection between these syndromes is unknown.[104]

Management

A number of treatments have been found to be effective, including fiber, talk therapy, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication, and peppermint oil.[105][106][107]

Diet

FODMAP

FODMAPs are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. A 2018 systematic review found that although there is evidence of improved IBS symptoms with a low FODMAP diet, the evidence is of very low quality.[108] Symptoms most likely to improve on this type of diet include urgency, flatulence, bloating,[109] abdominal pain, and altered stool output. One national guideline advises a low FODMAP diet for managing IBS when other dietary and lifestyle measures have been unsuccessful.[110] The diet restricts various carbohydrates which are poorly absorbed in the small intestine, as well as fructose and lactose, which are similarly poorly absorbed in those with intolerances to them. Reduction of fructose and fructan has been shown to reduce IBS symptoms in a dose-dependent manner in people with fructose malabsorption and IBS.[111]

FODMAPs are fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols, which are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and subsequently fermented by the bacteria in the distal small and proximal large intestine. This is a normal phenomenon, common to everyone. The resultant production of gas potentially results in bloating and flatulence.[112] Although FODMAPs can produce certain digestive discomfort in some people, not only do they not cause intestinal inflammation, but they help avoid it, because they produce beneficial alterations in the intestinal flora that contribute to maintaining the good health of the colon.[113][114][115] FODMAPs are not the cause of irritable bowel syndrome nor other functional gastrointestinal disorders, but rather a person develops symptoms when the underlying bowel response is exaggerated or abnormal.[112]

A low-FODMAP diet consists of restricting them from the diet. They are globally trimmed, rather than individually, which is more successful than for example restricting only fructose and fructans, which are also FODMAPs, as is recommended for those with fructose malabsorption.[112]

A low-FODMAP diet might help to improve short-term digestive symptoms in adults with irritable bowel syndrome,[116][110][117][16] but its long-term follow-up can have negative effects because it causes a detrimental impact on the gut microbiota and metabolome.[118][110][16][119] It should only be used for short periods of time and under the advice of a specialist.[120] A low-FODMAP diet is highly restrictive in various groups of nutrients and can be impractical to follow in the long-term.[121] More studies are needed to assess the true impact of this diet on health.[110][16]

In addition, the use of a low-FODMAP diet without verifying the diagnosis of IBS may result in misdiagnosis of other conditions such as celiac disease.[122] Since the consumption of gluten is suppressed or reduced with a low-FODMAP diet, the improvement of the digestive symptoms with this diet may not be related to the withdrawal of the FODMAPs, but of gluten, indicating the presence of unrecognized celiac disease, avoiding its diagnosis and correct treatment, with the consequent risk of several serious health complications, including various types of cancer.[122][123]

Fiber

Some evidence suggests soluble fiber supplementation (e.g., psyllium/ispagula husk) is effective.[15] It acts as a bulking agent, and for many people with IBS-D, allows for a more consistent stool. For people with IBS-C, it seems to allow for a softer, moister, more easily passable stool.[citation needed]

However, insoluble fiber (e.g., bran) has not been found to be effective for IBS.[124][125] In some people, insoluble fiber supplementation may aggravate symptoms.[126][127]

Fiber might be beneficial in those who have a predominance of constipation. In people who have IBS-C, soluble fiber can reduce overall symptoms but will not reduce pain. The research supporting dietary fiber contains conflicting small studies complicated by the heterogeneity of types of fiber and doses used.[128]

One meta-analysis found only soluble fiber improved global symptoms of irritable bowel, but neither type of fiber reduced pain.[128] An updated meta-analysis by the same authors also found soluble fiber reduced symptoms, while insoluble fiber worsened symptoms in some cases.[129] Positive studies have used 10–30 grams per day of ispaghula (psyllium).[130][131] One study specifically examined the effect of dose, and found 20 g of ispaghula (psyllium) were better than 10 g and equivalent to 30 g per day.[132]

Physical Activity

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential beneficial effects of physical activity on irritable bowel syndrome. Some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated a beneficial effect of physical activity on IBS symptoms. Three RCTs showed a significant improvement in Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Severity Scoring System, while 1 RCT showed a significant improvement only in symptoms of constipation.[133] In light of this, the latest British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of IBS have stated that all patients with IBS should be advised to take regular exercise (strong recommendation, weak certainty evidence),[134] whereas the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines have suggested with a lower certainty of evidence.[135] Exercise is Medicine recently provided simple practical indications based on world health organization guidelines,[136] which should be followed when physicians prescribing exercise training. As shown by the previous studies, a good Physical activity prescription during the visit could significantly improve patients’ adherence and, consequently, lead to a significant clinical benefit for symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.[133]

Medication

Medications that may be useful include antispasmodics such as dicyclomine and antidepressants.[137] Both H1-antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers have shown efficacy in reducing pain associated with visceral hypersensitivity in IBS.[30]

Serotonergic agents

A number of 5-HT3 antagonists or 5-HT4 agonists were proposed clinically to treat diarrhea-predominant IBS and constipation-predominant IBS, respectively. However, severe side effects have resulted in its withdrawal by food and drug administration and are now prescribed under emergency investigational drug protocol.[138] Other 5-HT receptor subtypes, such as 5-HT7 receptor, have yet to be developed.

Laxatives

For people who do not adequately respond to dietary fiber, osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol, sorbitol, and lactulose can help avoid "cathartic colon" which has been associated with stimulant laxatives.[139] Lubiprostone is a gastrointestinal agent used for the treatment of constipation-predominant IBS.[140]

Antispasmodics

The use of antispasmodic drugs (e.g., anticholinergics such as hyoscyamine or dicyclomine) may help people who have cramps or diarrhea. A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration concludes if seven people are treated with antispasmodics, one of them will benefit.[137] Antispasmodics can be divided into two groups: neurotropics and musculotropics. Musculotropics, such as mebeverine, act directly at the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal tract, relieving spasm without affecting normal gut motility.[citation needed] Since this action is not mediated by the autonomic nervous system, the usual anticholinergic side effects are absent.[141] The antispasmodic otilonium may also be useful.[142]

Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) used to suppress stomach acid production may cause small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) leading to IBS symptoms.[143] Discontinuation of PPIs in selected individuals has been recommended as it may lead to an improvement or resolution of IBS symptoms.[144]

Antidepressants

Evidence is conflicting about the benefit of antidepressants in IBS. Some meta-analyses have found a benefit, while others have not.[145] There is good evidence that low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can be effective for IBS.[137][146] With TCAs, about one in three people improve.[147]

However, the evidence is less robust for the effectiveness of other antidepressant classes such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs). Because of their serotonergic effect, SSRIs have been studied in IBS, especially for people who are constipation predominant. As of 2015, the evidence indicates that SSRIs do not help.[148] Antidepressants are not effective for IBS in people with depression, possibly because lower doses of antidepressants than the doses used to treat depression are required for relief of IBS.[149]

Other agents

Magnesium aluminum silicates and alverine citrate drugs can be effective for IBS.[150][127]

Rifaximin may be useful as a treatment for IBS symptoms, including abdominal bloating and flatulence, although relief of abdominal distension is delayed.[41][151] It is especially useful where small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is involved.[41]

In individuals with IBS and low levels of vitamin D supplementation is recommended. Some evidence suggests that vitamin D supplementation may improve symptoms of IBS, but further research is needed before it can be recommended as a specific treatment for IBS.[59][60]

Psychological therapies

There is low quality evidence from studies with poor methodological quality that psychological therapies can be effective in the treatment of IBS.[149] Reducing stress may reduce the frequency and severity of IBS symptoms. Techniques that may be helpful include regular exercise, such as swimming, walking, or running.[152]

Vagus nerve stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation has anti-inflammatory effects and its potential for the treatment of IBS is actively researched.[153][154][155]

Alternative medicine

A meta-analysis found no benefits of acupuncture relative to placebo for IBS symptom severity or IBS-related quality of life.[156]

Probiotics

Probiotics can be beneficial in the treatment of IBS; taking 10 billion to 100 billion beneficial bacteria per day is recommended for beneficial results. However, further research is needed on individual strains of beneficial bacteria for more refined recommendations.[151][157] Probiotics have positive effects such as enhancing the intestinal mucosal barrier, providing a physical barrier, bacteriocin production (resulting in reduced numbers of pathogenic and gas-producing bacteria), reducing intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation, and regulating the immune system both locally and systemically among other beneficial effects.[84] Probiotics may also have positive effects on the gut–brain axis by their positive effects countering the effects of stress on gut immunity and gut function.[158]

A number of probiotics have been found to be effective, including Lactobacillus plantarum,[84] and Bifidobacteria infantis;[159] but one review found only Bifidobacteria infantis showed efficacy.[160] B. infantis may have effects beyond the gut via it causing a reduction of proinflammatory cytokine activity and elevation of blood tryptophan levels, which may cause an improvement in symptoms of depression.[161] Some yogurt is made using probiotics that may help ease symptoms of IBS.[162] A probiotic yeast called Saccharomyces boulardii has some evidence of effectiveness in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.[163]

Certain probiotics have different effects on certain symptoms of IBS. For example, Bifidobacterium breve, B. longum, and Lactobacillus acidophilus have been found to alleviate abdominal pain. B. breve, B. infantis, L. casei, or L. plantarum species alleviated distension symptoms. B. breve, B. infantis, L. casei, L. plantarum, B. longum, L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, and Streptococcus salivarius ssp. thermophilus have all been found to affect flatulence levels. Most clinical studies show probiotics do not improve straining, sense of incomplete evacuation, stool consistency, fecal urgency, or stool frequency, although a few clinical studies did find some benefit of probiotic therapy. The evidence is conflicting for whether probiotics improve overall quality of life scores.[164]

Probiotics may exert their beneficial effects on IBS symptoms via preserving the gut microbiota, normalisation of cytokine blood levels, improving the intestinal transit time, decreasing small intestine permeability, and by treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth of fermenting bacteria.[164] A fecal transplant does not appear useful as of 2019.[165]

Herbal remedies

Peppermint oil appears useful.[166] In a meta-analysis it was found to be superior to placebo for improvement of IBS symptoms, at least in the short term.[107] An earlier meta-analysis suggested the results of peppermint oil were tentative as the number of people studied was small and blinding of those receiving treatment was unclear.[105] Safety during pregnancy has not been established, however, and caution is required not to chew or break the enteric coating; otherwise, gastroesophageal reflux may occur as a result of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Occasionally, nausea and perianal burning occur as side effects.[125] Iberogast, a multi-herbal extract, was found to be superior in efficacy to placebo.[167] A comprehensive meta-analysis using twelve random trials resulted that the use of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for adults with irritable bowel syndrome.[168]

Research into cannabinoids as treatment for IBS is limited. GI propulsion, secretion, and inflammation in the gut are all modulated by the ECS (Endocannabinoid system), providing a rationale for cannabinoids as treatment candidates for IBS.[169]

Only limited evidence exists for the effectiveness of other herbal remedies for IBS. As with all herbs, it is wise to be aware of possible drug interactions and adverse effects.[125]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of IBS varies by country and by age range examined. The bar graph at right shows the percentage of the population reporting symptoms of IBS in studies from various geographic regions (see table below for references). The following table contains a list of studies performed in different countries that measured the prevalence of IBS and IBS-like symptoms:

| Location | Prevalence | Author/year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 6%[170] | Boivin, 2001 | |

| Japan | 10%[171] | Quigley, 2006 | Study measured prevalence of GI abdominal pain/cramping |

| United Kingdom | 8.2%[172]

10.5%[173] |

Ehlin, 2003 Wilson, 2004 |

Prevalence increased substantially 1970–2004 |

| United States | 14.1%[174] | Hungin, 2005 | Most undiagnosed |

| United States | 15%[170] | Boivin, 2001 | Estimate |

| Pakistan | 14%[175] | Jafri, 2007 | Much more common in 16–30 age range. 56% male, 44% female |

| Pakistan | 34%[176] | Jafri, 2005 | College students |

| Mexico City | 35%[177] | Schmulson, 2006 | n=324. Also measured functional diarrhea and functional vomiting. High rates attributed to "stress of living in a populated city." |

| Brazil | 43%[171] | Quigley, 2006 | Study measured prevalence of GI abdominal pain/cramping |

| Mexico | 46%[171] | Quigley, 2006 | Study measured prevalence of GI abdominal pain/cramping |

Gender

In western countries, women are around two to three times more likely to be diagnosed with IBS and four to five times more likely to seek specialty care for it than men.[178] However, women in East Asian countries are not more likely than men to have irritable bowel syndrome, and there are conflicting reports about the female predominance of the disease in Africa and other parts of Asia.[179] People diagnosed with IBS are usually younger than 45 years old.[1] Studies of females with IBS show symptom severity often fluctuates with the menstrual cycle, suggesting hormonal differences may play a role.[180] Endorsement of gender-related traits has been associated with quality of life and psychological adjustment in IBS.[181] The increase in gastrointestinal symptoms during menses or early menopause may be related to declining or low estrogen and progesterone, suggesting that estrogen withdrawal may play a role in IBS.[182] Gender differences in healthcare-seeking may also play a role.[183] Gender differences in trait anxiety may contribute to lower pain thresholds in women, putting them at greater risk for a number of chronic pain disorders.[184] Finally, sexual trauma is a major risk factor for IBS, as are other forms of abuse.[185] Because women are at higher risk of sexual abuse than men, sex-related risk of abuse may contribute to the higher rate of IBS in women.[186]

History

The concept of an "irritable bowel" was introduced by P.W. Brown, first in The Journal Of The Kansas Medical Society in 1947[187] and later in the Rocky Mountain Medical Journal in 1950.[188] The term was used to categorize people who developed symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, and constipation, but where no well-recognized infective cause could be found. Early theories suggested the irritable bowel was caused by a psychosomatic or mental disorder.[189]

Society and culture

Economics

United States

The aggregate cost of irritable bowel syndrome in the United States has been estimated at $1.7–10 billion in direct medical costs, with an additional $20 billion in indirect costs, for a total of $21.7–30 billion.[9] A study by a managed care company comparing medical costs for people with IBS to non-IBS controls identified a 49% annual increase in medical costs associated with a diagnosis of IBS.[190] People with IBS incurred average annual direct costs of $5,049 and $406 in out-of-pocket expenses in 2007.[191] A study of workers with IBS found that they reported a 34.6% loss in productivity, corresponding to 13.8 hours lost per 40 hour week.[192] A study of employer-related health costs from a Fortune 100 company conducted with data from the 1990s found people with IBS incurred US$4527 in claims costs vs. $3276 for controls.[193] A study on Medicaid costs conducted in 2003 by the University of Georgia College of Pharmacy and Novartis found IBS was associated in an increase of $962 in Medicaid costs in California, and $2191 in North Carolina. People with IBS had higher costs for physician visits, outpatients visits, and prescription drugs. The study suggested the costs associated with IBS were comparable to those found for people with asthma.[194]

Research

Individuals with IBS have been found to have decreased diversity and numbers of Bacteroidota microbiota. Preliminary research into the effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplant in the treatment of IBS has been very favourable with a 'cure' rate of between 36 percent and 60 percent with remission of core IBS symptoms persisting at 9 and 19 months follow up.[195][196] Treatment with probiotic strains of bacteria has shown to be effective, though not all strains of microorganisms confer the same benefit and adverse side effects have been documented in a minority of cases.[197]

There is increasing evidence for the effectiveness of mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) in the treatment of IBS.[198] Mesalazine is a drug with anti-inflammatory properties that has been reported to significantly reduce immune mediated inflammation in the gut of IBS affected individuals with mesalazine therapy resulting in improved IBS symptoms as well as feelings of general wellness in IBS affected people. It has also been observed that mesalazine therapy helps to normalise the gut flora which is often abnormal in people who have IBS. The therapeutic benefits of mesalazine may be the result of improvements to the epithelial barrier function.[199] Treatment based on "abnormally" high IgG antibodies cannot be recommended.[200]

Differences in visceral sensitivity and intestinal physiology have been noted in IBS. Mucosal barrier reinforcement in response to oral 5-HTP was absent in IBS compared to controls.[201] IBS/IBD individuals are less often HLA DQ2/8 positive than in upper functional gastrointestinal disease and healthy populations.[202]

In other species

A similar syndrome is found in rats (Rattus spp.).[203] In rats a short-chain fatty acid receptor is involved.[203] Karaki et al., 2006 finds a free fatty acid receptor 2 subtype – GPR43 – that is expressed in both enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells.[203] These cells then respond in an exaggerated way to the IBS rat's own large quantity of maldigestion products.[203]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Definition and Facts for Irritable Bowel Syndrome". 23 February 2015. http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/Pages/definition-facts.aspx.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Symptoms and Causes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome". 23 February 2015. http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/Pages/symptoms-causes.aspx.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 "Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review". JAMA 313 (9): 949–58. March 2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0954. PMID 25734736.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Celiac disease: an immune dysregulation syndrome". Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 44 (11): 324–7. December 2014. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.10.002. PMID 25499458.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome". 23 February 2015. http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/Pages/treatment.aspx.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Treatment level 1". Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Diagnosis and Clinical Management (First ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 2013. ISBN 9781118444740. https://books.google.com/books?id=qSAruYVwLLcC&pg=PT295.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Costs of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK and US". PharmacoEconomics 24 (1): 21–37. 2006. doi:10.2165/00019053-200624010-00002. PMID 16445300.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10 (7): 712–721.e4. July 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. PMID 22426087. "Pooled prevalence in all studies was 11.2% (95% CI, 9.8%-12.8%). The prevalence varied according to country (from 1.1% to 45.0%) and criteria used to define IBS... Women are at slightly higher risk for IBS than men.".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 10 (4): 299–309. 2004. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.4.299. PMID 15298528.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications?". Gastroenterology 122 (4): 1140–56. April 2002. doi:10.1053/gast.2002.32392. PMID 11910364. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/downloads/zs25xj11x.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20360016.

- ↑ "Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome". Gastroenterology 136 (6): 1979–88. May 2009. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. PMID 19457422.

- ↑ "The role of stress on physiologic responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome". Gastroenterology 140 (3): 761–5. March 2011. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.032. PMID 21256129.

- ↑ Palsson, Olafur S.; Peery, Anne; Seitzberg, Dorthe; Amundsen, Ingvild Dybdrodt; McConnell, Bruce; Simrén, Magnus (2020-12-07). "Human Milk Oligosaccharides Support Normal Bowel Function and Improve Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Multicenter, Open-Label Trial". Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 11 (12): e00276. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000276. PMID 33512807.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 109 (9): 1367–74. September 2014. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.195. PMID 25070054.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Systematic review: dietary fibre and FODMAP-restricted diet in the management of constipation and irritable bowel syndrome". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 41 (12): 1256–70. June 2015. doi:10.1111/apt.13167. PMID 25903636.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine 358 (16): 1692–9. April 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. PMID 18420501.

- ↑ Jung, Hye-Kyung (April 2011). "Is There True Gender Difference of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Asia?". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 17 (2): 206–207. doi:10.5056/jnm.2011.17.2.206. PMID 21603006. "However, some Asian studies fail to report significant gender differences in the prevalence of IBS.6"

- ↑ Canavan, Caroline; West, Joe; Card, Timothy (4 February 2014). "The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome". Clinical Epidemiology 6: 71–80. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S40245. ISSN 1179-1349. PMID 24523597. "In South Asia, South America, and Africa, rates of IBS in men are much closer to those of women, and in some cases higher. Consequently, if prevalence is stratified according to geographic region, no significant sex difference can be seen in these areas.80"

- ↑ Women and Health. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press. 2000. p. 1098. ISBN 9780122881459. https://books.google.com/books?id=zSCgj8LXFHAC&pg=PA1098.

- ↑ "Diagnosing the patient with abdominal pain and altered bowel habits: is it irritable bowel syndrome?". American Family Physician 67 (10): 2157–2162. May 2003. PMID 12776965. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20030515/2157.html.

- ↑ "Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome". Clinical Infectious Diseases (Oxford University Press) 46 (4): 594–599. February 2008. doi:10.1086/526774. PMID 18205536.

- ↑ "An Update on Post-infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Role of Genetics, Immune Activation, Serotonin and Altered Microbiome". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 18 (3): 258–268. July 2012. doi:10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.258. PMID 22837873.

- ↑ "Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome" (in English). Gastroenterology 124 (6): 1662–1671. May 2003. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00324-X. PMID 12761724.

- ↑ "Therapy of the postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: an update". Clujul Medical 90 (2): 133–138. 2017. doi:10.15386/cjmed-752. PMID 28559695.

- ↑ "Diagnostic approach to the patient with irritable bowel syndrome". The American Journal of Medicine 107 (5A): 20S–26S. November 1999. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00278-8. PMID 10588169.

- ↑ Fifth Edition: Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company. 2011. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Irritable bowel syndrome". Internal Medicine Journal 36 (11): 724–8. November 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01217.x. PMID 17040359.

- ↑ "Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Co-morbid Gastrointestinal and Extra-gastrointestinal Functional Syndromes". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 16 (2): 113–9. April 2010. doi:10.5056/jnm.2010.16.2.113. PMID 20535341.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "The role of mast cells in functional GI disorders". Gut 65 (1): 155–68. January 2016. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309151. PMID 26194403.

- ↑ "Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 7 (3): 163–173. March 2010. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. PMID 20101257.

- ↑ "An Allergic Basis for Abdominal Pain". The New England Journal of Medicine 384 (22): 2156–2158. June 2021. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2104146. PMID 34077648.

- ↑ "Association between body mass index and fecal calprotectin levels in children and adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome". Medicine 101 (32): e29968. August 2022. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000029968. PMID 35960084.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Irritable bowel syndrome". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 2: 16014. March 2016. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.14. PMID 27159638.

- ↑ "Systematic review and meta-analysis: The incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 26 (4): 535–544. August 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03399.x. PMID 17661757.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 "World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a Global Perspective". World Gastroenterology Organisation. Sep 2015. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines/irritable-bowel-syndrome-english-2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Manipulation of the microbiota for treatment of IBS and IBD-challenges and controversies". Gastroenterology 146 (6): 1554–1563. May 2014. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.050. PMID 24486051.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: mechanistic insights into chronic disturbances following enteric infection". World Journal of Gastroenterology 20 (14): 3976–85. April 2014. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3976. PMID 24744587.

- ↑ "Brain-gut response to stress and cholinergic stimulation in irritable bowel syndrome. A preliminary study". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 17 (2): 133–41. September 1993. doi:10.1097/00004836-199309000-00009. PMID 8031340.

- ↑ "New insights in the etiology and pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome: contribution of neonatal stress models". Pediatric Research 62 (3): 240–5. September 2007. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3180db2949. PMID 17622962.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 "Rifaximin for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials". Medicine 95 (4): e2534. January 2016. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002534. PMID 26825893.

- ↑ "Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management". Gut 56 (12): 1770–98. December 2007. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.119446. PMID 17488783.

- ↑ "Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in irritable bowel syndrome and intestinal inflammation". Journal of Gastroenterology 42 (Suppl 17): 48–51. January 2007. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1942-7. PMID 17238026.

- ↑ "Post-infectious IBS". March 8, 2021. https://aboutibs.org/what-is-ibs-sidenav/post-infectious-ibs.html.

- ↑ "Rome Foundation Working Team Report on Post-Infection Irritable Bowel Syndrome" (in en). Gastroenterology 156 (1): 46–58.e7. January 2019. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.011. PMID 30009817. PMC 6309514. https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)34766-8/abstract.

- ↑ "Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: the missing link". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 14 (7): 435–441. July 2017. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.37. PMID 28513629.

- ↑ "Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Gastroenterology 53 (7): 807–818. July 2018. doi:10.1007/s00535-018-1476-9. PMID 29761234.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: meaningful association or unnecessary hype". World Journal of Gastroenterology 20 (10): 2482–91. March 2014. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2482. PMID 24627585.

- ↑ "Gut microbiota as potential orchestrators of irritable bowel syndrome". Gut and Liver 9 (3): 318–31. May 2015. doi:10.5009/gnl14344. PMID 25918261.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "A role for the gut microbiota in IBS". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 11 (8): 497–505. August 2014. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.40. PMID 24751910.

- ↑ "Yeast metabolic products, yeast antigens and yeasts as possible triggers for irritable bowel syndrome". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 17 (1): 21–6. January 2005. doi:10.1097/00042737-200501000-00005. PMID 15647635.

- ↑ "Dientamoeba fragilis: an emerging role in intestinal disease". CMAJ 175 (5): 468–9. August 2006. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060265. PMID 16940260.

- ↑ "Seasonal prevalence of intestinal parasites in the United States during 2000". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 66 (6): 799–803. June 2002. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.799. PMID 12224595.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis". International Journal for Parasitology 37 (1): 11–20. January 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.009. PMID 17070814.

- ↑ "Blastocystis, an unrecognized parasite: an overview of pathogenesis and diagnosis". Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease 1 (5): 167–78. October 2013. doi:10.1177/2049936113504754. PMID 25165551. "Recent in vitro and in vivo studies have shed new light on the pathogenic power of this parasite, suggesting that Blastocystis sp. infection is associated with a variety of gastrointestinal disorders, may play a significant role in irritable bowel syndrome, and may be linked with cutaneous lesions (urticaria).".

- ↑ "Update on the pathogenic potential and treatment options for Blastocystis sp". Gut Pathogens 6: 17. 2014. doi:10.1186/1757-4749-6-17. PMID 24883113.

- ↑ "The role of Blastocystis sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Parasitology Research 116 (9): 2361–2371. September 2017. doi:10.1007/s00436-017-5535-6. PMID 28668983.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome: the need to exclude Dientamoeba fragilis". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 72 (5): 501; author reply 501–2. May 2005. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.5.0720501. PMID 15891119. http://www.ajtmh.org/cgi/content/full/72/5/501.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Vitamin D status in irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of supplementation on symptoms: what do we know and what do we need to know?". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 72 (10): 1358–1363. October 2018. doi:10.1038/s41430-017-0064-z. PMID 29367731. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127402/3/Williams%20et%20al%20EJCN%20Body%20Text%20R2%20Clean.pdf.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "The role of vitamin D in reducing gastrointestinal disease risk and assessment of individual dietary intake needs: Focus on genetic and genomic technologies". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 60 (1): 119–33. January 2016. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201500243. PMID 26251177.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome: a review of the general aspects and the potential role of vitamin D". Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13 (4): 345–359. April 2019. doi:10.1080/17474124.2019.1570137. PMID 30791775.

- ↑ "Ion channelopathies in functional GI disorders". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 311 (4): G581–G586. 2016. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00237.2016. PMID 27514480.

- ↑ "The role of the SCN5A-encoded channelopathy in irritable bowel syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders". Neurogastroenterology & Motility 27 (7): 906–13. 2015. doi:10.1111/nmo.12569. PMID 25898860.

- ↑ "Genes and environment in irritable bowel syndrome: one step forward". Gut 55 (12): 1694–6. December 2006. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.108837. PMID 17124153.

- ↑ "5-HT 7 receptor-dependent intestinal neurite outgrowth contributes to visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome". Laboratory Investigation 102 (9): 1023–1037. 2022. doi:10.1038/s41374-022-00800-z. PMID 35585132.

- ↑ "Intestinal dysbiosis in irritable bowel syndrome: etiological factor or epiphenomenon?". Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 10 (4): 389–93. May 2010. doi:10.1586/erm.10.33. PMID 20465494.

- ↑ "Microbiota, gastrointestinal infections, low-grade inflammation, and antibiotic therapy in irritable bowel syndrome: an evidence-based review" (in es). Revista de Gastroenterologia de Mexico 79 (2): 96–134. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2014.01.004. PMID 24857420.

- ↑ "The role of genetics in IBS". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 40 (1): 45–67. March 2011. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.011. PMID 21333900.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Do published guidelines for evaluation of irritable bowel syndrome reflect practice?". BMC Gastroenterology 1: 11. 2001. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-1-11. PMID 11701092.

- ↑ "Screening for Celiac Disease in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 112 (1): 65–76. January 2017. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.466. PMID 27753436. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/106483/3/AJG-16-1318R1%20CLEAN.pdf. "Although IBS is not a diagnosis of exclusion, with physicians advised to minimize the use of investigations, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has a limited repertoire of symptoms, meaning that abdominal pain and a change in bowel habit is not specific to the disorder.".

- ↑ "Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV". Gastroenterology 150 (6): 1262–1279.e2. February 2016. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032. PMID 27144617. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/downloads/12579z328.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine". World Journal of Gastroenterology 20 (22): 6759–73. June 2014. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6759. PMID 24944467.

- ↑ "Rome IV Criteria" (in en-US). https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/.

- ↑ "Evidence- and consensus-based practice guidelines for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome". Archives of Internal Medicine 161 (17): 2081–8. September 2001. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.17.2081. PMID 11570936.

- ↑ "A unifying hypothesis for the functional gastrointestinal disorders: really multiple diseases or one irritable gut?". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders 6 (2): 72–8. 2006. PMID 16699476.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review. CRC Press. 2005. p. 225–. ISBN 978-0-203-50274-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=nStxzRQlNaAC&pg=PA225. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis". World Journal of Gastroenterology 18 (37): 5151–63. October 2012. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5151. PMID 23066308.

- ↑ 78.00 78.01 78.02 78.03 78.04 78.05 78.06 78.07 78.08 78.09 78.10 78.11 "Nonceliac gluten sensitivity". Gastroenterology 148 (6): 1195–204. May 2015. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. PMID 25583468.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 79.4 79.5 79.6 79.7 79.8 "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a work-in-progress entity in the spectrum of wheat-related disorders". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology 29 (3): 477–91. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.04.006. PMID 26060112.

- ↑ "Fibromyalgia and nutrition: what news?". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 33 (1 Suppl 88): S117-25. 2015. PMID 25786053.

- ↑ "[Is gluten the great etiopathogenic agent of disease in the XXI century?]". Nutricion Hospitalaria 30 (6): 1203–10. December 2014. doi:10.3305/nh.2014.30.6.7866. PMID 25433099.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 82.5 82.6 82.7 82.8 "Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders". Nutrients 5 (10): 3839–53. September 2013. doi:10.3390/nu5103839. PMID 24077239.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 "Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity". BMJ 351: h4347. October 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4347. PMID 26438584.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 "Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics. An etiopathogenic approach at last?". Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas 101 (8): 553–64. August 2009. doi:10.4321/s1130-01082009000800006. PMID 19785495.

- ↑ "Testing for celiac sprue in irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea: a cost-effectiveness analysis". Gastroenterology 126 (7): 1721–32. June 2004. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.012. PMID 15188167. https://zenodo.org/record/1235988.

- ↑ "The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and functional dyspepsia in patients with irritable bowel syndrome". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 95 (8): 1900–5. August 2000. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02252.x. PMID 10950033.

- ↑ "H. pylori infection and visceral hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Digestive Diseases 19 (2): 170–3. 2001. doi:10.1159/000050673. PMID 11549828.

- ↑ "Giardia lamblia infection in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia: a prospective study". World Journal of Gastroenterology 12 (12): 1941–4. March 2006. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i12.1941. PMID 16610003.

- ↑ "Lactose malabsorption and irritable bowel syndrome. Effect of a long-term lactose-free diet". The Italian Journal of Gastroenterology 27 (3): 117–21. April 1995. PMID 7548919.

- ↑ "An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 104 (Suppl 1): S1-35. January 2009. doi:10.1038/ajg.2008.122. PMID 19521341. http://www.nature.com/ajg/journal/v104/n1s/pdf/ajg2008122a.pdf.

- ↑ "Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 30 (7): 707–17. October 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04081.x. PMID 19570102.

- ↑ "Migraine, fibromyalgia, and depression among people with IBS: a prevalence study". BMC Gastroenterology 6: 26. September 2006. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-6-26. PMID 17007634.

- ↑ "Ion channelopathies in functional GI disorders". Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311 (4): G581–G586. October 2016. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00237.2016. PMID 27514480.

- ↑ "Gastrointestinal manifestations in myotonic muscular dystrophy". World J Gastroenterol 12 (12): 1821–1828. March 2006. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i12.1821. PMID 16609987.

- ↑ "Is irritable bowel syndrome a low-grade inflammatory bowel disease?". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 34 (2): 235–45, vi–vii. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.007. PMID 15862932.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: interrelated diseases?". Chinese Journal of Digestive Diseases 6 (3): 122–32. 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1443-9573.2005.00202.x. PMID 16045602.

- ↑ "Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 97 (2): 389–96. February 2002. doi:10.1016/S0002-9270(01)04037-0. PMID 11866278.

- ↑ "IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior". Digestive Diseases and Sciences 49 (3): 469–74. March 2004. doi:10.1023/B:DDAS.0000020506.84248.f9. PMID 15139501.

- ↑ "Detection of colorectal tumor and inflammatory bowel disease during follow-up of patients with initial diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 35 (3): 306–11. March 2000. doi:10.1080/003655200750024191. PMID 10766326.

- ↑ "Gallstones, cholecystectomy and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) MICOL population-based study". Digestive and Liver Disease 40 (12): 944–50. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.013. PMID 18406218.

- ↑ "The incidence of abdominal and pelvic surgery among patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Digestive Diseases and Sciences 50 (12): 2268–75. December 2005. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-3047-1. PMID 16416174.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome and surgery: a multivariable analysis". Gastroenterology 126 (7): 1665–73. June 2004. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.020. PMID 15188159.

- ↑ "Endometriosis is associated with prevalence of comorbid conditions in migraine". Headache 47 (7): 1069–78. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00784.x. PMID 17635599.

- ↑ "Interstitial cystitis: Risk factors". Mayo Clinic. January 20, 2009. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/interstitial-cystitis/DS00497/DSECTION=4.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 337: a2313. November 2008. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2313. PMID 19008265.

- ↑ "Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 109 (9): 1350–65; quiz 1366. September 2014. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.148. PMID 24935275.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 "Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 48 (6): 505–12. July 2014. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a88357. PMID 24100754.

- ↑ "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Efficacy of a Gluten-Free Diet and a Low FODMAPs Diet in Treating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 113 (9): 1290–1300. September 2018. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0195-4. PMID 30046155. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/134755/.

- ↑ Pessarelli, T., Sorge, A., Elli, L., & Costantino, A. The Gluten-free Diet and the Low-FODMAP Diet in the Management of Functional Abdominal Bloating and Distension. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2680.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 110.3 "Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 11 (4): 256–66. April 2014. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2013.259. PMID 24445613. "An emerging body of research now demonstrates the efficacy of fermentable carbohydrate restriction in IBS. [...] However, further work is urgently needed both to confirm clinical efficacy of fermentable carbohydrate restriction in a variety of clinical subgroups and to fully characterize the effect on the gut microbiota and the colonic environ¬ment. Whether the effect on luminal bifidobacteria is clinically relevant, preventable, or long lasting, needs to be investigated. The influence on nutrient intake, dietary diversity, which might also affect the gut microbiota,137 and quality of life also requires further exploration as does the possible economic effects due to reduced physician contact and need for medication. Although further work is required to confirm its place in IBS and functional bowel disorder clinical pathways, fermentable carbohydrate restriction is an important consideration for future national and international IBS guidelines.".

- ↑ "Dietary fructose intolerance, fructan intolerance and FODMAPs". Current Gastroenterology Reports 16 (1): 370. January 2014. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0370-0. PMID 24357350.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 "Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 25 (2): 252–8. February 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x. PMID 20136989.

- ↑ "The Overlap between Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Clinical Dilemma". Nutrients 7 (12): 10417–26. December 2015. doi:10.3390/nu7125541. PMID 26690475.

- ↑ "Microbial induction of immunity, inflammation, and cancer". Frontiers in Physiology 1: 168. 2011. doi:10.3389/fphys.2010.00168. PMID 21423403.

- ↑ "Role of dietary fiber and short-chain fatty acids in the colon". Current Pharmaceutical Design 9 (4): 347–58. 2003. doi:10.2174/1381612033391973. PMID 12570825.

- ↑ "Does a low FODMAPs diet reduce symptoms of functional abdominal pain disorders? A systematic review in adult and paediatric population, on behalf of Italian Society of Pediatrics". Italian Journal of Pediatrics 44 (1): 53. May 2018. doi:10.1186/s13052-018-0495-8. PMID 29764491.

- ↑ "Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis". European Journal of Nutrition 55 (3): 897–906. April 2016. doi:10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1. PMID 25982757.

- ↑ "Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols: role in irritable bowel syndrome". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 8 (7): 819–34. September 2014. doi:10.1586/17474124.2014.917956. PMID 24830318.

- ↑ "A healthy gastrointestinal microbiome is dependent on dietary diversity". Molecular Metabolism 5 (5): 317–320. May 2016. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2016.02.005. PMID 27110483.

- ↑ "The low FODMAP diet: recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS". Gut 66 (8): 1517–1527. August 2017. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313750. PMID 28592442. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/the-low-fodmap-diet(c7f6c885-e206-4fa4-8206-576e70bd3d59).html.

- ↑ "Diet and inflammatory bowel disease: review of patient-targeted recommendations". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 12 (10): 1592–600. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.063. PMID 24107394. "Even less evidence exists for the efficacy of the SCD, FODMAP, or Paleo diet. Furthermore, the practicality of maintaining these interventions over long periods of time is doubtful. At a practical level, adherence to defined diets may result in an unnecessary financial burden or reduction in overall caloric intake in people who are already at risk for protein-calorie malnutrition.".

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 "How to institute the low-FODMAP diet". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 32 (Suppl 1): 8–10. March 2017. doi:10.1111/jgh.13686. PMID 28244669. "Common symptoms of IBS are bloating, abdominal pain, excessive flatus, constipation, diarrhea, or alternating bowel habit. These symptoms, however, are also common in the presentation of coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, defecatory disorders, and colon cancer. Confirming the diagnosis is crucial so that appropriate therapy can be undertaken. Unfortunately, even in these alternate diagnoses, a change in diet restricting FODMAPs may improve symptoms and mask the fact that the correct diagnosis has not been made. This is the case with coeliac disease where a low-FODMAP diet can concurrently reduce dietary gluten, improving symptoms, and also affecting coeliac diagnostic indices.3,4 Misdiagnosis of intestinal diseases can lead to secondary problems such as nutritional deficiencies, cancer risk, or even mortality in the case of colon cancer.".

- ↑ "Celiac disease". World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. July 2016. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/celiac-disease/celiac-disease-english.

- ↑ "Bran and irritable bowel syndrome: time for reappraisal". Lancet 344 (8914): 39–40. July 1994. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91055-3. PMID 7912305.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 "Complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". Canadian Family Physician 55 (2): 143–8. February 2009. PMID 19221071.

- ↑ "Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial". BMJ 339 (b3154): b3154. August 2009. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3154. PMID 19713235.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 "[Irritable bowel syndrome: current treatment options]". Presse Médicale 36 (11 Pt 2): 1619–26. November 2007. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2007.03.008. PMID 17490849.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 "Systematic review: the role of different types of fibre in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 19 (3): 245–51. February 2004. doi:10.1111/j.0269-2813.2004.01862.x. PMID 14984370.

- ↑ "Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial". BMJ 339 (b): b3154. August 2009. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3154. PMID 19713235.

- ↑ "Double blind study of ispaghula in irritable bowel syndrome". Gut 28 (11): 1510–3. November 1987. doi:10.1136/gut.28.11.1510. PMID 3322956.

- ↑ "Ispaghula therapy in irritable bowel syndrome: improvement in overall well-being is related to reduction in bowel dissatisfaction". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 5 (5): 507–13. 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.1990.tb01432.x. PMID 2129822.

- ↑ "Optimum dosage of ispaghula husk in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: correlation of symptom relief with whole gut transit time and stool weight". Gut 28 (2): 150–5. February 1987. doi:10.1136/gut.28.2.150. PMID 3030900.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Costantino A, Pessarelli T, Vecchiato M, Vecchi M, Basilisco G, Ermolao A. A practical guide to the proper prescription of physical activity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [published online ahead of print, 2022 Sep 21]. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;S1590-8658(22)00663-6. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2022.08.034

- ↑ Vasant DH, Paine PA, Black CJ, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2021;70(7):1214-1240. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324598

- ↑ Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):17-44. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036

- ↑ WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 "Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 (8): CD003460. August 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. PMID 21833945.

- ↑ "Efficacy of 5-HT3 antagonists and 5-HT4 agonists in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Gastroenterology 104 (7): 1831–1843. 2009. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.223. PMID 19471254.

- ↑ "Alterations in colonic anatomy induced by chronic stimulant laxatives: the cathartic colon revisited". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 26 (4): 283–6. June 1998. doi:10.1097/00004836-199806000-00014. PMID 9649012.

- ↑

- "Lubiprostone Is Effective in the Treatment of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 91 (4): 456–468. April 2016. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.01.015. PMID 27046523. "Lubiprostone is a safe and efficacious drug for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, with limited adverse effects in 3 months of follow-up.".

- "Lubiprostone: MedlinePlus Drug Information". 2017. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a607034.html. "Lubiprostone is also used to treat irritable bowel syndrome with constipation... in women who are at least 18 years of age."

- "Lubiprostone Oral: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Pictures, Warnings & Dosing - WebMD". https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-95017/lubiprostone-oral/details.

- "Lubiprostone (Oral Route) Side Effects - Mayo Clinic". 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/lubiprostone-oral-route/side-effects/drg-20069057?p=1.

- ↑ Further Essentials of Pharmacology for Nurses. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). 1 June 2012. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-335-24398-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=BjhFBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA34.

- ↑ "Role of antispasmodics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". World Journal of Gastroenterology 20 (20): 6031–43. May 2014. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6031. PMID 24876726.

- ↑ "Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy". Gut and Liver 11 (2): 196–208. March 2017. doi:10.5009/gnl16126. PMID 28274108.

- ↑ "Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report". Gut 62 (1): 159–76. January 2013. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302167. PMID 22730468.

- ↑ "Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adults". UpToDate Inc.. http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=gi_dis/5811&selectedTitle=1~148&source=search_result#9.

- ↑ "Effect of Antidepressants and Psychological Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 114 (1): 21–39. January 2019. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5. PMID 30177784. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/135430/2/AJG-18-087R1%20CLEAN.pdf.

- ↑ "Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Medicine 108 (1): 65–72. January 2000. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00299-5. PMID 11059442.

- ↑ "Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressants for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE 10 (8): e0127815. 7 August 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127815. PMID 26252008. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1027815X.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Korea, 2017 Revised Edition". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 24 (2): 197–215. April 2018. doi:10.5056/jnm17145. PMID 29605976.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic Agents for Chronic Diarrhea". Intestinal Research 13 (4): 306–12. October 2015. doi:10.5217/ir.2015.13.4.306. PMID 26576135.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 "Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 48 (10): 1044–1060. November 2018. doi:10.1111/apt.15001. PMID 30294792.